UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performing Citizens and Subjects: Dance and Resistance in Twenty-First Century Mozambique Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1w33f4s5 Author Montoya, Aaron Tracy Publication Date 2016 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ PERFORMING CITIZENS AND SUBJECTS: DANCE AND RESISTANCE IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY MOZAMBIQUE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in ANTHROPOLOGY with an emphasis in Visual Studies by Aaron Montoya June 2016 The Dissertation of Aaron Montoya is approved: ____________________________________ Professor Shelly Errington, Chair ____________________________________ Professor Carolyn Martin-Shaw ____________________________________ Professor Olga Nájera-Ramírez ____________________________________ Professor Lisa Rofel ____________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Aaron T. Montoya 2016 Table of Contents Abstract iv Agradecimientos vi Introduction 1 1. Citizens and Subjects in Portuguese Mozambique 20 2. N’Tsay 42 3. Nyau 84 4. Um Solo para Cinco 145 5. Feeling Plucked: Labor in the Cultural Economy 178 6. Conclusion 221 Bibliography 234 iii Abstract Performing Citizens and Subjects: Dance and Resistance in Twenty-First Century Mozambique Aaron Montoya This dissertation examines the politics and economics of the cultural performance of dance, placing this expressive form of communication within the context of historic changes in Mozambique, from the colonial encounter, to the liberation movement and the post-colonial socialist nation, to the neoliberalism of the present. The three dances examined here represent different regimes, contrasting forms of subjectivity, and very different relations of the individual to society. -

Shutt E Remains Flown to Dover for Examinatiori

An Associated Collegiate Press Pacemaker Award Winner • THE • Akira Kurosawa films Dela\lare lose<; to G:\IU. featured at Prince Theater, 71-63, Bl B8 • on-Protit Org. 250 Student Center • University of Delaware • Newark, DE 19716 L'S. p.._1..,tage Patd Tuesday & Friday . e\\ ~u·k. 0[ Pennit n. 2t1 FREE Volume 129, Issue 29;?'·:·- · ,: :· - .: . '~~ -.: . ,:Yww.review.udel.edu · . · Friday, February 7, 2003 -.-~ -..;--~ £~- ~ .... _ . Shutt e remains flown to Dover for examinatiori B\ \SHLE\ 01 '-;1· :\ n:cen mg r.:matns for months ·· an identification proces'>. anJ then are ··we in Delaware join "ith the rest of "We are tnvestigattng cver)thing \\e Gt:ttle satd the base has p.:rsonnel prrparcd to be released to the next of k.in. the counlr) and the world 111 grieving this can think of,'' Thomp'>on sard "We arc Rem.<tns fn>m the -.e'en a-.tronauts '' ork.tng in the mortuary 24 hours per day. "We treat the remains with the honor loss and pra]ing for the victims and their U'>tng reports from people who have found k.dkd "hen the sp.t~e -.huttle Cnlumbta s.:,·en day' per week. and dignity they deserve:· he \<lid. .. 0 u r families. l\1en and women who reach for debns on thetr property." dtstntegratcd ,lturda) \\l!t\' n:c.:ned D) the Dtl\er·, ~ite. he said. ts the on ly people at the mortuat'} are specially trained the stars as they dtd capture our She '>atd Investigators ha\ e founq Chatle-. C Car,lln Ct'nter for .\lortuary fac!Iit\ in the continental Cmted States for thts type of event. -

The New World

THE NEW WORLD: A STORY OF THE INDIES Written by Terrence Malick Capt John Smith, an English adventurer John Rolfe, a tobacco planter Capt Newport, first President of the Jarnestown Colony Master Wingfield, a gentleman Capt Argall, a soldier of fortune Mary, a maid Ben, a friend of Smith1s Wilf, a cabin boy Capt Ratclif fe, Newport's aide King James and Queen Anne Ackley, Jonson, Selway, Emery, Robinson; colonists The Indiana Pccahontas, a young princess The Great Powhatan, her father, Emperor of the Indians Opechancanough, Powhatan's brother Parahunt, Pocahontas1 brother Patowomeck, King of Pastancy, her treacherous uncle Wobblehead, a lunatic Tomocomo, Powhatan' s interpreter With various fortune-seekers of the Jarnestown Colony, court officials of Werowocomoco, Chiefs of the Parnunkey Armies, etc. 'lPocahontaseasily prevailed with her father and her countrymen to allow her to indulge her passion for the captain, by often visiting the fort, and always accompanying her visits with a fresh supply of provisions: therefore it may justly be said, that the success of our first settlement in America, was chiefly owing to the love this girl had conceived for Capt Smith, and consequently in this instance, as well as in many others, LOVE DOES ALL THAT'S GREAT BELOW! " "A Short Account of the British Plantations in America, London Magazine, 1755 TITLES OVER BLACK, CUS OF POCAHONTAS t The title appears: -: (and dissolves to) The front credits follow,- over shots of our heroine learning English from our hero. She repeats one word after another: tree, bush, leaf, bird, cloud. 1 LEGEND - EXT. SEA Alegend appears over the wild, unbounded sea. -

© 2021 Andrew Gregory Page 1 of 13 RECORDINGS Hard Rock / Metal

Report covers the period of January 1st to Penny Knight Band - "Cost of Love" March 31st, 2021. The inadvertently (single) [fusion hard rock] Albany missed few before that time period, which were brought to my attention by fans, Remains Of Rage - "Remains Of Rage" bands & others, are listed at the [hardcore metal] Troy end,along with an End Note. Senior Living - "The Paintbox Lace" (2- track) [alternative grunge rock shoegaze] Albany Scavengers - "Anthropocene" [hardcore metal crust punk] Albany Thank you to Nippertown.com for being a partner with WEXT Radio in getting this report out to the people! Scum Couch - "Scum Couch | Tree Walker Split" [experimental noise rock] Albany RECORDINGS Somewhere In The Dark - "Headstone" (single track) Hard Rock / Metal / Punk [hard rock] Glenville BattleaXXX - "ADEQUATE" [clitter rock post-punk sasscore] Albany The Frozen Heads - "III" [psychedelic black doom metal post-punk] Albany Bendt - "January" (single) [alternative modern hard rock] Albany The Hauntings - "Reptile Dysfunction" [punk rock] Glens Falls Captain Vampire - "February Demos" [acoustic alternative metalcore emo post-hardcore punk] Albany The One They Fear - "Perservere" - "Metamorphosis" - "Is This Who We Are?" - "Ignite" (single tracks) Christopher Peifer - "Meet Me at the Bar" - "Something [hardcore metalcore hard rock] Albany to Believe In" (singles) [garage power pop punk rock] Albany/NYC The VaVa Voodoos - "Smash The Sun" (single track) [garage punk rock] Albany Dave Graham & The Disaster Plan - "Make A Scene" (single) [garage -

284 Chapter 4 Compilasians: from Asian Underground To

CHAPTER 4 COMPILASIANS: FROM ASIAN UNDERGROUND TO ASIAN FLAVAS Introduction The success of those British Asian popular musicians who were associated with the Asian Underground by the end of the 1990s had two imagined outcomes: 1) their success could establish British Asians as significant contributors to British society and popular culture, or 2) their success could eventually falter and, as a result, return British Asian popular musicians to the margins of British society. As Chapter 2 demonstrates, the second outcome proved to become reality; British Asian musicians associated with the Asian Underground did return to the margins of “British culture” as popularly conceived. Before they returned to the margins, recording companies released a plethora of recordings by British Asian musicians, as well as compilation recordings prominently incorporating their music. As shown in Chapter 2, the “world music” category in the context of the award ceremonies served many simultaneous, if at times contradictory, roles that helped define British Asian musicians’ relation to mainstream culture; the most significant of these roles included serving as a dumping ground for exotic others and as a highly visible platform highlighting British Asian musicians’ specific contributions to the music industry. Yet British Asian musicians’ participation within particular compilation recordings offers yet another significant forum that defines their cultural identity. The first British Asian-oriented compilations had been motivated by attempts to capture the atmosphere of particular club scenes and package them for mass consumption; as a result, these compilations most often featured music by artists associated with respective clubs. Yet as a surfeit of 284 British Asian releases saturated the market, British Asian music lost its novelty. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Hannah Robinson Complete CV

Hannah Robinson Songwriter (Topline / Melody) / Singer British songwriter and singer, Hannah Robinson began her career as a vocalist, working internationally, and has since become one of the UK’s most significant, in-demand top-line writers. Collaborations include producers such as Richard X, Liam Howe and Jim Elliot on some of her most successful co-writes, such as Rachel Steven’s No.2 hit ‘Some Girls’, Ladyhawke’s ‘My Delirium’ and Annie’s ‘Chewing Gum’, establishing Hannah as an ‘A’ list writer on the global pop stage. Lana Del Rey ‘Born to Die’/Album Tracks Liam Howe Icona Pop Forthcoming Album Elof Loelv/Fredrick Berger Kylie Minogue ‘Can’t Beat The Feeling’ / Album Tracks Matt Prime / Pascal Gabriel Sophie Ellis-Bextor ‘Make A Scene’ / Single Freemasons / Biff ‘Trip The Light Fantastic’ / Single Matt Prime / Pascal Gabriel St Etienne ‘Method of Modern Love’ / Single Richard x / Matt Prime Sound of Arrows Forthcoming Tracks Richard X / Liam Howe CocknBull Kid ‘Yellow' / Single Liam Howe ‘Hoarder’ / Single Liam Howe Emiil Forthcoming Tracks Fred Ball Sugababes ‘Down Down’ / Single Johnny Rockstar The Saturdays ‘Why Me Why Now’ / Single Paul Statham Ladyhawke ‘My Delirium’ / Single Pascal Gabriel / Alex Grey ’Dusk Til’ Dawn’ / Single Pascal Gabriel / Alex Grey Annie ‘Annie’ / Album Tracks Richard X ElectroVamp ‘Drinks Taste…’ / Single Liam Howe Jamelia ‘Walk With Me’ / Single Matt Prime Rachel Stevens ‘Some Girls’ / Single Richard X ‘So Good’ / Single Pascal Gabriel Geri Halliwell ‘Passion’ / Single Ian Masterton Carl Cox Give Me Your -

San Diego Public Library New Additions February 2008

MAYOR JERRY SANDERS San Diego Public Library New Additions February 2008 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities Biographies 100 - Philosophy & Psychology California Room 200 - Religion CD-ROMs 300 - Social Sciences Compact Discs 400 - Language DVD Videos/Videocassettes 500 - Science eBooks 600 - Technology Fiction 700 - Art Foreign Languages 800 - Literature Genealogy Room 900 - Geography & History Graphic Novels Audiocassettes Large Print Audiovisual Materials Fiction Call # Author Title FIC/ABBOTT Abbott, Jeff. Panic FIC/ACHEBE Achebe, Chinua. Things fall apart FIC/ACKROYD Ackroyd, Peter, 1949- The fall of Troy FIC/ADAIR Adair, Cherry, 1951- White heat : a novel FIC/ADICHIE Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi Half of a yellow sun [MYST] FIC/ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. Spanish dagger [MYST] FIC/ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. The tale of Hawthorn House : the cottage tales of Beatrix Potter FIC/ALBOM Albom, Mitch, 1958- The five people you meet in heaven FIC/ALI Ali, Monica, 1967- Alentejo blue : fiction FIC/ALLEN Allen, Sarah Addison. Garden spells FIC/ALLENDE Allende, Isabel. Daughter of fortune : a novel FIC/ALLENDE Allende, Isabel. Forest of the Pygmies FIC/AMIRREZVANI Amirrezvani, Anita. The blood of flowers : a novel [SCI-FI] FIC/ANTHONY Anthony, Piers. Vale of the vole [MYST] FIC/ARRUDA Arruda, Suzanne Middendorf The serpent's daughter : a Jade Del Cameron mystery FIC/ASWANI Aswānī, Alā, 1957- The Yacoubian building FIC/AUDEGUY Audeguy, Stéphane. The theory of clouds FIC/AUEL Auel, Jean M. The plains of passage FIC/AUEL Auel, Jean M. The shelters of stone : Earth's children FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane Persuasion FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane Pride and prejudice FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane Sense and sensibility : authoritative text, contexts, criticism FIC/BABCOCK Babcock, Joe, 1979- The boys and the bees FIC/BALDACCI Baldacci, David. -

Successful Parenting & Family Practices

Teacher Guide MICHIGAN ADULT EDUCATION SUCCESSFUL PARENTING & FAMILY PRACTICES Table of Contents Introduction to the Teacher ...................................................................................................................... i Lesson Plans ..................................................................................................................................................1 Lesson 1.1: Family Budget & Frugal Spending — The Wilson’s Story .................................................................... 3 Lesson 1.2: Family Budgeting for Health Insurance– The Wilson’s Story, Part 2 .........................................5 Lesson 1.3: Creating Credit Card Chaos — Amy’s Story ............................................................................................... 7 Lesson 1.4: Baby Goes to College: Student Loans, Scholarships, FAFSA – The Santiago’s story ..........9 Lesson 1.5: Teaching Young Adults About Money Management — Bianca’s story. Part 1 ....................11 Lesson 1.6: Teaching Children about Money – Bianca’s story Part 2 ..............................................................13 Lesson 2.1: Dealing with childhood obesity – Karla’s story: Part One ................................................................15 Lesson 2.2 Dealing with childhood obesity – Karla’s story: Part Two ..................................................................17 Lesson 2.3 Dealing with Diabetes – Marge’s story .....................................................................................................19 -

Philip GUY Davis 1936-2014

[email protected] @NightshiftMag nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 233 December Oxford’s Music Magazine 2014 “Our riffs would kick Godzilla’s arse” OXFORD DUPLICATION CENTRE Also in this issue: [email protected] Office: 01865 457000 Mobile: 07917 775477 Supporting Oxfordshire Bands with RIDE - Return of the OX 4! Affordable Professional CD Duplication Jonny come home! FANTASTIC BAND RATES Radiohead star announces Oxford show ON ALL SERVICES Professional Thermal Printed CDs Full Colour/Black & White GAZ IS BACK - second album due soon Silver or White Discs Design Work Support Oxford remembers Philip Guy Davis Digital Printing Packaging Options Introducing Charlie Cunningham Fulfilment plus Recommended by Matchbox Recordings Ltd, Poplar Jake, Undersmile, Desert Storm, Turan Audio Ltd, Nick Cope, Prospeckt, Paul Jeffries, Alvin All your Oxford music news, reviews and gigs Roy, Pete The Temp, Evolution, Coozes, Blue Moon and many more... NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net THE OXFORD PUNT returns next workshops and children’s activities. year for another showcase of local Tickets from Truck Store or music talent. The annual festival www.woodfestival.com takes place on Wednesday 13th May across five venues in Oxford THE DREAMING SPIRES city centre – The Purple Turtle, release their second album, The Cellar, The Wheatsheaf, The `Searching For The Supertruth’, on RIDE HAVE REFORMED FOR A SERIES OF SHOWS IN 2015. The Turl Street Kitchen and The White February 23rd next year. The new legendary Oxford band will play live together for the first time in 20 years, Rabbit. -

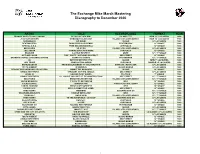

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020 ARTIST TITLE RECORD LABEL FORMAT YEAR FRANKIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD RELAX (12" SEX MIX) ISLAND / ZTT NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 JOCEYLYN BROWN SOMEBODY ELSES GUY ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 SHRIEKBACK GO BANG! ISLAND LP LACQUERS 1988 BEATMASTERS BURN IT UP (ACID REMIX) RHYTHM KING 12" SINGLE 1988 SPECIAL A.K.A. FREE NELSON MANDELA CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS SO GOOD ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY LP LACQUERS 1988 JELLYBEAN COMING BACK FOR MORE CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 ERASURE A LITTLE RESPECT MUTE 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 OUTLAW POSSE THE * PARTY / OUTLAWS IN EFFECT GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 BRANDON COOKE & ROXANNE SHANTE SHARP AS A KNIFE PHONOGRAM 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 U2 WITH OR WITHOUT YOU ISLAND NEW 7" LACQUERS 1988 JUDI TZUKE COMPILATION ALBUM CHRYSALIS DOUBLE LP LACQUERS 1988 NAPALM DEATH FROM ENSLAVEMENT TO OBLITERATION EARACHE / REVOLVER LP LACQUERS 1988 TOOTS HIBBERT IN MEMPHIS ISLAND MANGO LP LACQUERS 1988 REGGAE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA MINNIE THE MOOCHER ISLAND 12" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS STRAIGHT OUT THE JUNGLE GEE STREET LP LACQUERS 1988 LEVEL 42 HEAVEN IN MY HANDS POLYDOR 7" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS I'LL HOUSE YOU (GEE ST. RECONSTRUCTION) GEE STREET 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS BREATHE LIFE INTO ME ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 BLOW MONKEYS IT PAYS TO BE TWELVE RCA 12" SINGLE 1988 STEVEN DANTE IMAGINATION CHRYSALIS COOLTEMPO 12" SINGLE 1988 TANITA TIKARAM TWIST IN MY SOBRIETY WEA 10" SINGLE 1988 RICHIE RICH MY D.J. (PUMP IT UP SOME) GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 TODD TERRY WEEKEND SLEEPING BAG UK 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 TRAVELING WILBURYS HANDLE WITH CARE WEA 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 YOUNG M.C. -

Mike Marsh Discography

Mike Marsh Discography ARTIST TITLE RECORD LABEL FORMAT YEAR 02:54 SUGAR POLYDOR / FICTION DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 1789 CA IRA MON AMOUR UNIVERSAL MERCURY FRANCE CD SINGLE / DOWNLOAD 2011 0 8 0 0 1 VORAGINE WORKING PROGRESS CD ALBUM 2007 18 WHEELER THE HOURS AND THE TIMES CREATION CD SINGLE / 12" SINGLE 1996 18 WHEELER YEAR ZERO CREATION CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1996 49ERS GOT TO BE FREE ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1992 4GOTTEN FLOOR THE FORGOTTEN FLOOR JATO MUSIC CD ALBUM 2008 808 STATE DON SOLARIS ZTT CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1996 808 STATE BOND ZTT CD SINGLE / 12" / 10" SINGLE 1996 808 STATE LOPEZ ZTT CD SINGLE / 12" SINGLE 1996 AARON BIRDS IN THE STORM WAGRAM / CINQ 7 CD ALBUM / DOWNLOAD 2010 ABC GREATEST HITS PHONOGRAM CD PRE-MASTERING 1990 ADAM CLAYTON & LARRY MULLEN MISSION : IMPOSSIBLE MOTHER 7" SINGLE 1996 ADAM KESHER CHALLENGING NATURE DISQUE PRIMEUR CD ALBUM / DOWNLOAD 2010 ADD N TO (X) AVANT HARD MUTE CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1998 ADD N TO (X) REVENGE OF THE BLACK REGENT MUTE CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1999 ADD N TO (X) LOUD LIKE NATURE MUTE CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 2002 ADDIE BRIK LOVED HUNGRY BREAKIN' BEATS CD ALBUM 2003 ADDIE BRIK STRIKE THE TENT ADDIE BRIK CD ALBUM 2008 ADELE SET FIRE TO THE RAIN (THOMAS GOLD REMIX) XL RECORDINGS CD SINGLE / DOWNLOAD 2011 ADRENALIN JUNKIES ADRENALIN JUNKIES LA PLAGE CD ALBUM 2008 ADSTEDT DREAMING WIDE AWAKE VERATONE SWITZERLAND DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 AFTERGLOW NEVER GROW OLD EP JACK McDONALD DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 AGENT PROVOCATEUR RED TAPE EPIC CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1996