Lumbar Radicular Pain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Herniated Disc Brochure

AN INTRODUCTION TO HERNIATED DISCS This booklet provides general information on herniated discs. It is not meant to replace any personal conversations that you might wish to have with your physician or other member of your healthcare team. Not all the information here will apply to your individual treatment or its outcome. About the Spine CERVICAL The human spine is comprised 24 bones or vertebrae in the cervical (neck) spine, the thoracic (chest) spine, and the lumbar (lower back) THORACIC spine, plus the sacral bones. Vertebrae are connected by several joints, which allow you to bend, twist, and carry loads. The main joint LUMBAR between two vertebrae is called an intervertebral disc. The disc is comprised of two parts, a tough and fibrous outer layer (annulus fibrosis) SACRUM and a soft, gelatinous center (nucleus pulposus). These two parts work in conjunction to allow the spine to move, and also provide shock absorption. INTERVERTEBRAL ANNULUS DISC FIBROSIS SPINAL NERVES NUCLEUS PULPOSUS Each vertebrae has an opening (vertebral foramen) through which a tubular bundle of spinal nerves and VERTEBRAL spinal nerve roots travel. FORAMEN From the cervical spine to the mid-lumbar spine this bundle of nerves is called the spinal cord. The bundle is then referred to as the cauda equina through the bottom of the spine. At each level of the spine, spinal nerves exit the spinal cord and cauda equina to both the left and right sides. This enables movement and feeling throughout the body. What is a Herniated Disc? When the gelatinous center of the intervertebral disc pushes out through a tear in the fibrous wall, the disc herniates. -

Peroneal Neuropathy Misdiagnosed As L5 Radiculopathy: a Case Report Michael D Reife1,2* and Christopher M Coulis3,4,5

Reife and Coulis Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2013, 21:12 http://www.chiromt.com/content/21/1/12 CHIROPRACTIC & MANUAL THERAPIES CASE REPORT Open Access Peroneal neuropathy misdiagnosed as L5 radiculopathy: a case report Michael D Reife1,2* and Christopher M Coulis3,4,5 Abstract Objective: The purpose of this case report is to describe a patient who presented with a case of peroneal neuropathy that was originally diagnosed and treated as a L5 radiculopathy. Clinical features: A 53-year old female registered nurse presented to a private chiropractic practice with complaints of left lateral leg pain. Three months earlier she underwent elective left L5 decompression surgery without relief of symptoms. Intervention and outcome: Lumbar spine MRI seven months prior to lumbar decompression surgery revealed left neural foraminal stenosis at L5-S1. The patient symptoms resolved after she stopped crossing her legs. Conclusion: This report discusses a case of undiagnosed peroneal neuropathy that underwent lumbar decompression surgery for a L5 radiculopathy. This case study demonstrates the importance of a thorough clinical examination and decision making that ensures proper patient diagnosis and management. Keywords: Peroneal neuropathy, Lumbar radiculopathy, Chiropractic Background Case presentation The most common entrapment neuropathy in the lo- The patient is a 53-year-old registered nurse who was wer extremity is common peroneal mononeuropathy, ac- referred to the author’s office in August 2003 by her pri- counting for approximately 15% of all mononeuropathies mary care physician with a chief complaint of left leg in adults [1]. Most injuries occur at the fibular head and pain. Her symptoms began in October 2002 after she fell can be the result of many factors including chronic low off an ambulance landing on her left hip. -

An Audit of Bone Mineral Density and Associated Factors in Patients With

Review Article Clinician’s corner Images in Medicine Experimental Research Case Report Miscellaneous Letter to Editor DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2019/39690.12544 Original Article Postgraduate Education An Audit of Bone Mineral Density and Case Series Associated Factors in Patients with Orthopaedics Section Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Short Communication ARASH RAHBAR1, RAHMATOLLAH JOKAR2, SEYED MOKHTAR ESMAEILNEJAD-GANJI3 ABSTRACT Results: Overall, 146 patients with lumbar stenosis were Introduction: Osteoporosis is a major global health problem enrolled. Based on bone densitometry of spine and femur, and is commonly observed with lumbar stenosis in older 35 (24%) and 36 (24.7%) of the patients had osteoporosis. people. It is stated that osteoporosis may cause progressive According to femoral densitometry, age (OR=1.311, 95% CI: spinal deformities and stenosis in elderly patients. 1.167-1.473), being a female (OR=3.391, 95% CI: 1.391-8.420) and being a homemaker (OR=3.675, 95% CI: 1.476-9.146) Aim: To audit prevalence of low bone mineral density and were found as risk factors for osteoporosis. Based on spinal associated factors in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. densitometry, age (OR=1.283, 95% CI: 1.154-1.427) and being Materials and Methods: Patients with symptomatic lumbar a female (OR=2.786, 95% CI: 1.106-7.019) were associated with spinal stenosis were recruited in this cross-sectional study, osteoporosis. Significant correlations were observed between who had been referred to Shahid Beheshti hospital in Babol, bone mineral density and red blood cell counts (r=+0.168, Northern Iran, between 2016 and 2017. -

Vertebral Column and Thorax

Introduction to Human Osteology Chapter 4: Vertebral Column and Thorax Roberta Hall Kenneth Beals Holm Neumann Georg Neumann Gwyn Madden Revised in 1978, 1984, and 2008 The Vertebral Column and Thorax Sternum Manubrium – bone that is trapezoidal in shape, makes up the superior aspect of the sternum. Jugular notch – concave notches on either side of the superior aspect of the manubrium, for articulation with the clavicles. Corpus or body – flat, rectangular bone making up the major portion of the sternum. The lateral aspects contain the notches for the true ribs, called the costal notches. Xiphoid process – variably shaped bone found at the inferior aspect of the corpus. Process may fuse late in life to the corpus. Clavicle Sternal end – rounded end, articulates with manubrium. Acromial end – flat end, articulates with scapula. Conoid tuberosity – muscle attachment located on the inferior aspect of the shaft, pointing posteriorly. Ribs Scapulae Head Ventral surface Neck Dorsal surface Tubercle Spine Shaft Coracoid process Costal groove Acromion Glenoid fossa Axillary margin Medial angle Vertebral margin Manubrium. Left anterior aspect, right posterior aspect. Sternum and Xyphoid Process. Left anterior aspect, right posterior aspect. Clavicle. Left side. Top superior and bottom inferior. First Rib. Left superior and right inferior. Second Rib. Left inferior and right superior. Typical Rib. Left inferior and right superior. Eleventh Rib. Left posterior view and left superior view. Twelfth Rib. Top shows anterior view and bottom shows posterior view. Scapula. Left side. Top anterior and bottom posterior. Scapula. Top lateral and bottom superior. Clavicle Sternum Scapula Ribs Vertebrae Body - Development of the vertebrae can be used in aging of individuals. -

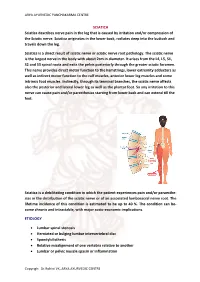

SCIATICA Sciatica Describes Nerve Pain in the Leg That Is Caused by Irritation And/Or Compression of the Sciatic Nerve

ARYA AYURVEDIC PANCHAKARMA CENTRE SCIATICA Sciatica describes nerve pain in the leg that is caused by irritation and/or compression of the Sciatic nerve. Sciatica originates in the lower back, radiates deep into the buttock and travels down the leg. Sciatica is a direct result of sciatic nerve or sciatic nerve root pathology. The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the body with about 2cm in diameter. It arises from the L4, L5, S1, S2 and S3 spinal roots and exits the pelvis posteriorly through the greater sciatic foramen. This nerve provides direct motor function to the hamstrings, lower extremity adductors as well as indirect motor function to the calf muscles, anterior lower leg muscles and some intrinsic foot muscles. Indirectly, through its terminal branches, the sciatic nerve affects also the posterior and lateral lower leg as well as the plantar foot. So any irritation to this nerve can cause pain and/or paresthesias starting from lower back and can extend till the feet. Sciatica is a debilitating condition in which the patient experiences pain and/or paraesthe- sias in the distribution of the sciatic nerve or of an associated lumbosacral nerve root. The lifetime incidence of this condition is estimated to be up to 40 %. The condition can be- come chronic and intractable, with major socio-economic implications. ETIOLOGY • Lumbar spinal stenosis • Herniated or bulging lumbar intervertebral disc • Spondylolisthesis • Relative misalignment of one vertebra relative to another • Lumbar or pelvic muscle spasm or inflammation Copyrigh: Dr.Rohini VK, ARYA AYURVEDIC CENTRE ARYA AYURVEDIC PANCHAKARMA CENTRE • Spinal or Paraspinal masses included malignancy, epidural haematoma or epidural abscess • Lumbar degenerative disc disease • Sacroiliac joint dysfunction EPIDEMIOLOGY GENDER: There appears to be no gender predominance. -

Radiculopathy Vs. Spinal Stenosis: Evocative Electrodiagnosis Identifies the Main Pain Generator

Functional Electromyography Loren M. Fishman · Allen N. Wilkins Functional Electromyography Provocative Maneuvers in Electrodiagnosis 123 Loren M. Fishman, MD Allen N. Wilkins, MD College of Physicians & Surgeons Manhattan Physical Medicine Columbia University and Rehabilitation New York, NY 10028, USA New York, NY 10013, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-60761-019-9 e-ISBN 978-1-60761-020-5 DOI 10.1007/978-1-60761-020-5 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Library of Congress Control Number: 2010935087 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. The publisher makes no warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein. -

Nonoperative Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis with Neurogenic Claudication a Systematic Review

SPINE Volume 37, Number 10, pp E609–E616 ©2012, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins LITERATURE REVIEW Nonoperative Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis With Neurogenic Claudication A Systematic Review Carlo Ammendolia , DC, PhD, *†‡ Kent Stuber, DC, MSc , § Linda K. de Bruin , MSc , ‡ Andrea D. Furlan, MD, PhD , ||‡¶ Carol A. Kennedy, BScPT, MSc , ‡#** Yoga Raja Rampersaud, MD , †† Ivan A. Steenstra , PhD , ‡ and Victoria Pennick, RN, BScN, MHSc ‡‡ or methylcobalamin, improve walking distance. There is very low- Study Design. Systematic review. quality evidence from a single trial that epidural steroid injections Objective. To systematically review the evidence for the improve pain, function, and quality of life up to 2 weeks compared effectiveness of nonoperative treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis with home exercise or inpatient physical therapy. There is low- with neurogenic claudication. quality evidence from a single trial that exercise is of short-term Summary of Background Data. Neurogenic claudication benefi t for leg pain and function compared with no treatment. There can signifi cantly impact functional ability, quality of life, and is low- and very low-quality evidence from 6 trials that multimodal independence in the elderly. nonoperative treatment is less effective than indirect or direct Methods. We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, surgical decompression with or without fusion. and ICL databases up to January 2011 for randomized controlled Conclusion. Moderate- and high-GRADE evidence for nonopera- trials published in English, in which at least 1 arm provided tive treatment is lacking and thus prohibiting recommendations to data on nonoperative treatments. Risk of bias in each study was guide clinical practice. Given the expected exponential rise in the independently assessed by 2 reviewers using 12 criteria. -

Guidline for the Evidence-Informed Primary Care Management of Low Back Pain

Guideline for the Evidence-Informed Primary Care Management of Low Back Pain 2nd Edition These recommendations are systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances. They should be used as an adjunct to sound clinical decision making. Guideline Disease/Condition(s) Targeted Specifications Acute and sub-acute low back pain Chronic low back pain Acute and sub-acute sciatica/radiculopathy Chronic sciatica/radiculopathy Category Prevention Diagnosis Evaluation Management Treatment Intended Users Primary health care providers, for example: family physicians, osteopathic physicians, chiro- practors, physical therapists, occupational therapists, nurses, pharmacists, psychologists. Purpose To help Alberta clinicians make evidence-informed decisions about care of patients with non- specific low back pain. Objectives • To increase the use of evidence-informed conservative approaches to the prevention, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment in primary care patients with low back pain • To promote appropriate specialist referrals and use of diagnostic tests in patients with low back pain • To encourage patients to engage in appropriate self-care activities Target Population Adult patients 18 years or older in primary care settings. Exclusions: pregnant women; patients under the age of 18 years; diagnosis or treatment of specific causes of low back pain such as: inpatient treatments (surgical treatments); referred pain (from abdomen, kidney, ovary, pelvis, -

Brachial-Plexopathy.Pdf

Brachial Plexopathy, an overview Learning Objectives: The brachial plexus is the network of nerves that originate from cervical and upper thoracic nerve roots and eventually terminate as the named nerves that innervate the muscles and skin of the arm. Brachial plexopathies are not common in most practices, but a detailed knowledge of this plexus is important for distinguishing between brachial plexopathies, radiculopathies and mononeuropathies. It is impossible to write a paper on brachial plexopathies without addressing cervical radiculopathies and root avulsions as well. In this paper will review brachial plexus anatomy, clinical features of brachial plexopathies, differential diagnosis, specific nerve conduction techniques, appropriate protocols and case studies. The reader will gain insight to this uncommon nerve problem as well as the importance of the nerve conduction studies used to confirm the diagnosis of plexopathies. Anatomy of the Brachial Plexus: To assess the brachial plexus by localizing the lesion at the correct level, as well as the severity of the injury requires knowledge of the anatomy. An injury involves any condition that impairs the function of the brachial plexus. The plexus is derived of five roots, three trunks, two divisions, three cords, and five branches/nerves. Spinal roots join to form the spinal nerve. There are dorsal and ventral roots that emerge and carry motor and sensory fibers. Motor (efferent) carries messages from the brain and spinal cord to the peripheral nerves. This Dorsal Root Sensory (afferent) carries messages from the peripheral to the Ganglion is why spinal cord or both. A small ganglion containing cell bodies of sensory NCS’s sensory fibers lies on each posterior root. -

Inflammatory Back Pain in Patients Treated with Isotretinoin Although 3 NSAID Were Administered, Her Complaints Did Not Improve

Inflammatory Back Pain in Patients Treated with Isotretinoin Although 3 NSAID were administered, her complaints did not improve. She discontinued isotretinoin in the third month. Over 20 days her com- To the Editor: plaints gradually resolved. Despite the positive effects of isotretinoin on a number of cancers and In the literature, there are reports of different mechanisms and path- severe skin conditions, several disorders of the musculoskeletal system ways indicating that isotretinoin causes immune dysfunction and leads to have been reported in patients who are treated with it. Reactive seronega- arthritis and vasculitis. Because of its detergent-like effects, isotretinoin tive arthritis and sacroiliitis are very rare side effects1,2,3. We describe 4 induces some alterations in the lysosomal membrane structure of the cells, cases of inflammatory back pain without sacroiliitis after a month of and this predisposes to a degeneration process in the synovial cells. It is isotretinoin therapy. We observed that after termination of the isotretinoin thought that isotretinoin treatment may render cells vulnerable to mild trau- therapy, patients’ complaints completely resolved. mas that normally would not cause injury4. Musculoskeletal system side effects reported from isotretinoin treat- Activation of an infection trigger by isotretinoin therapy is complicat- ment include skeletal hyperostosis, calcification of tendons and ligaments, ed5. According to the Naranjo Probability Scale, there is a potential rela- premature epiphyseal closure, decreases in bone mineral density, back tionship between isotretinoin therapy and bilateral sacroiliitis6. It is thought pain, myalgia and arthralgia, transient pain in the chest, arthritis, tendonitis, that patients who are HLA-B27-positive could be more prone to develop- other types of bone abnormalities, elevations of creatine phosphokinase, ing sacroiliitis and back pain after treatment with isotretinoin, or that and rare reports of rhabdomyolysis. -

Substance P: Transmitter O. Nociception (Minireview)

ENDOCRINE REGULATIONS, Vol. 34,195201, 2000 195 SUBSTANCE P: TRANSMITTER O NOCICEPTION (MINIREVIEW) M. ZUBRZYCKA1, A. JANECKA2 1Department of Physiology and 2Department of General Chemistry, Institute of Physiology and Biochemistry, Medical University of Lodz, Lindleya 3, 90-131 Lodz, Poland E-mail: [email protected] Substance P plays the role of a neurotransmitter immunoreactive fibers has also been detected in lam- and neuromodulator in the central and peripheral ina V of the dorsal horn (LJUNGDAHL et al. 1978), lam- nervous system. The presence of substance P in de- ina X surrounding the central canal (LAMOTTE and myelinated sensory fibres, as well as in the small SHAPIRO 1991), the nucleus dorsalis, interomediolat- and medium-sized neurons of spinal dorsal horn sub- eral cell column, and the ventral horn (PIORO et stantia gelatinosa gives a structural basis for the al.1984). Electric stimulation of the dorsal root, or hypothesis that SP plays an important role of peripheral nerve endings, causes a substantial release a mediator in the processing of nociceptive informa- of SP within the substantia gelatinosa of spinal dor- tion. In this paper recent advances on the effect of sal horns (OTSUKA and KANISHI 1976). SP on conduction and modulation of nociceptive In the dorsal regions of the spinal dorsal horn, impulsation are reviewed. The studies concerning the besides SP also large quantities of gamma-aminobu- role of SP in the prevertebral ganglia and spinal dor- tyric acid (GABA) are present, but reduction of sal horns has been presented, including the distribu- GABA levels has no effect on the SP content, and tion of SP in the spinal cord, as well as its pre- and similarly, reduction of SP levels does not cause any postsynaptic actions on excitatory and inhibitory decrease of GABA concentration in this region of postsynaptic potentials (EPSP and IPSP) and the ef- the spinal cord (TAKAHASHI and OTSUKA 1975). -

Shoulder Pain – Complexity to Simplicity

Shoulder Pain – Complexity to Simplicity A Regional Approach to Shoulder Pain The best way to approach a problem of shoulder pain is to look at the pain from a regional point of view. This allows for easy identification of specific pathological problems that occur at each region. In this talk, we look at the patterns of pain that occur with the different regions around the shoulder. From this, we will focus on the pathological problems that can be expected in each region and then look at specific physical examination findings that can be used to confirm a diagnosis or help further clarify the problem. Although this talk is focused on the diagnosis of causes of shoulder pain, we also take a look at some updates and salient features of treatment. In general, pain in the region of the shoulder can be grouped into 4 main types. These relate to specific patterns of pain that allow history taking to help us focus on the likely cause(s) before moving on to examination. A fairly clear-cut diagnosis is almost always achievable without the need to resort to special tests to help make the diagnosis. Of course, this does not include all possible causes of pain. The uncommon problem will still need a thorough and complete approach to determining cause, often with the requirement for special investigations. Remember that this is a good guide. Don't neglect other causes of referred pain that may cause pain in and around the shoulder. Included here is cardiac pain, diaphragmatic pain, apical lung disease and malignant bone pain.