BRIDGING the SECOND INTERMEDIATE PERIOD Chris Bennett Phd FSO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012: Providence, Rhode Island

The 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt April 27-29, 2012 Renaissance Providence Hotel Providence, RI Photo Credits Front cover: Egyptian, Late Period, Saite, Dynasty 26 (ca. 664-525 BCE) Ritual rattle Glassy faience; h. 7 1/8 in Helen M. Danforth Acquisition Fund 1995.050 Museum of Art Rhode Island School of Design, Providence Photography by Erik Gould, courtesy of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Photo spread pages 6-7: Conservation of Euergates Gate Photo: Owen Murray Photo page 13: The late Luigi De Cesaris conserving paintings at the Red Monastery in 2011. Luigi dedicated himself with enormous energy to the suc- cess of ARCE’s work in cultural heritage preservation. He died in Sohag on December 19, 2011. With his death, Egypt has lost a highly skilled conservator and ARCE a committed colleague as well as a devoted friend. Photo: Elizabeth Bolman Abstracts title page 14: Detail of relief on Euergates Gate at Karnak Photo: Owen Murray Some of the images used in this year’s Annual Meeting Program Booklet are taken from ARCE conservation projects in Egypt which are funded by grants from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The Chronique d’Égypte has been published annually every year since 1925 by the Association Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth. It was originally a newsletter but rapidly became an international scientific journal. In addition to articles on various aspects of Egyptology, papyrology and coptology (philology, history, archaeology and history of art), it also contains critical reviews of recently published books. -

Was the Function of the Earliest Writing in Egypt Utilitarian Or Ceremonial? Does the Surviving Evidence Reflect the Reality?”

“Was the function of the earliest writing in Egypt utilitarian or ceremonial? Does the surviving evidence reflect the reality?” Article written by Marsia Sfakianou Chronology of Predynastic period, Thinite period and Old Kingdom..........................2 How writing began.........................................................................................................4 Scopes of early Egyptian writing...................................................................................6 Ceremonial or utilitarian? ..............................................................................................7 The surviving evidence of early Egyptian writing.........................................................9 Bibliography/ references..............................................................................................23 Links ............................................................................................................................23 Album of web illustrations...........................................................................................24 1 Map of Egypt. Late Predynastic Period-Early Dynastic (Grimal, 1994) Chronology of Predynastic period, Thinite period and Old Kingdom (from the appendix of Grimal’s book, 1994, p 389) 4500-3150 BC Predynastic period. 4500-4000 BC Badarian period 4000-3500 BC Naqada I (Amratian) 3500-3300 BC Naqada II (Gerzean A) 3300-3150 BC Naqada III (Gerzean B) 3150-2700 BC Thinite period 3150-2925 BC Dynasty 1 3150-2925 BC Narmer, Menes 3125-3100 BC Aha 3100-3055 BC -

ROYAL STATUES Including Sphinxes

ROYAL STATUES Including sphinxes EARLY DYNASTIC PERIOD Dynasties I-II Including later commemorative statues Ninutjer 800-150-900 Statuette of Ninuter seated wearing heb-sed cloak, calcite(?), formerly in G. Michaelidis colln., then in J. L. Boele van Hensbroek colln. in 1962. Simpson, W. K. in JEA 42 (1956), 45-9 figs. 1, 2 pl. iv. Send 800-160-900 Statuette of Send kneeling with vases, bronze, probably made during Dyn. XXVI, formerly in G. Posno colln. and in Paris, Hôtel Drouot, in 1883, now in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 8433. Abubakr, Abd el Monem J. Untersuchungen über die ägyptischen Kronen (1937), 27 Taf. 7; Roeder, Äg. Bronzefiguren 292 [355, e] Abb. 373 Taf. 44 [f]; Wildung, Die Rolle ägyptischer Könige im Bewußtsein ihrer Nachwelt i, 51 [Dok. xiii. 60] Abb. iv [1]. Name, Gauthier, Livre des Rois i, 22 [vi]. See Antiquités égyptiennes ... Collection de M. Gustave Posno (1874), No. 53; Hôtel Drouot Sale Cat. May 22-6, 1883, No. 53; Stern in Zeitschrift für die gebildete Welt 3 (1883), 287; Ausf. Verz. 303; von Bissing in 2 Mitteilungen des Kaiserlich Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung xxxviii (1913), 259 n. 2 (suggests from Memphis). Not identified by texts 800-195-000 Head of royal statue, perhaps early Dyn. I, in London, Petrie Museum, 15989. Petrie in Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland xxxvi (1906), 200 pl. xix; id. Arts and Crafts 31 figs. 19, 20; id. The Revolutions of Civilisation 15 fig. 7; id. in Anc. Eg. (1915), 168 view 4; id. in Hammerton, J. A. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Ranke, the Art of Ancient Egypt and Breasted, Geschichte Aegyptens (1936), 41-2; Smith, Hist

NON-ROYAL STATUES PREDYNASTIC PERIOD Woman with child Ivory. 801-110-000 Woman with child on hip, late Predynastic, in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 14441. Capart, Primitive Art in Egypt 168 fig. 131; Erman and Ranke, Aegypten und aegyptisches Leben im Altertum Taf. 12 [1]; Schäfer and Andrae, Kunst (1925), 574 Abb. 171 [5]; (1930), 606-7 Abb. 176 [4]; (1942), 626 Abb. 176 [4]; Scharff, Die Altertümer der Vor- und Frühzeit Ägyptens ii, 50-1 [79] Taf. 16; Ranke, The Art of Ancient Egypt and Breasted, Geschichte Aegyptens (1936), 41-2; Smith, Hist. Eg. Sculp. 1-2 fig. 4 [left]; Wolf, Kunst Abb. 18; Hornemann, Types v, pl. 1246; Wiesner, J. Ägyptische Kunst 26 Abb. 1; id. in Äg. Mus. (1991), No. 5 [b] fig. on 1; Vilímková, M. Starove9ký Egypt fig. 15; Priese, Das Ägyptische Museum. Wegleitung (1989), 11 Abb. 1; Wenig, Die Frau pl. 4; D. W[ildung] in Phillips, T. (ed.), Africa. The Art of a Continent Cat. 1.2 fig. 801-110-002 Mother with child, late Predynastic, in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 17600. Schäfer and Andrae, Kunst (1925), 574 Abb. 171 [2, 3]; (1930), 606 Abb. 176 [2, 3]; (1942), 626 Abb. 176 [2, 3]; Scharff, Die Altertümer der Vor- und Frühzeit Ägyptens ii, 50 [78] Taf. 16; Ranke, The Art of Ancient Egypt and Breasted, Geschichte Aegyptens (1936), 45-6; Hamann, Äg. Kunst 76, 78 Abb. 83; Smith, Hist. Eg. Sculp. 1-2 fig. 4 [middle]; Wolf, Kunst 53 Abb. 17; id. Die Kultur Ägyptens 50 Abb. 48; id. Frühe Hochkulturen. Ägypten, Mesopotamien, Ägäis 22 Abb. -

Catalog SCIROCCO

Главная Назад Каталог пирамид. Каталог ШИРОКО Дата публикации: 2013г. Версия 3 от 13.09.2013 [email protected] Кат. N: PYReg001.GIZ01.LpsIV Название: Пирамида фараона Хеопса (Cheops) Другие названия: Куфу(Khufu), Великая(Great); Лепсиуса IV(Lepsius IV), Kheops Координаты: 29°58'45.03''N 31°08'03.69''E Ориентир: Египет, Каир, Гиза (Egypt, Cairo, Giza) Форма: гладкая, наклон: 51.89° Материал: , камень (известняк) Размеры,м: 230x230x146.5 Азимут, °: 0 Коментарий:Самая большая из рукотворных пирамид M01, M02 000, 001, 002, 003, 004, 005, 006, Кат. N: PYReg002.GIZ02.LpsVIII Название: Пирамида фараона Хафры (Khafre) Другие названия: Хефрена(Khephren); Урт-Хафра (Hurt-Khafre); Лепсиус VIII(Lepsius VIII) Координаты: 29°58'34"N 31°07'51"E Ориентир: Египет, Каир, Гиза (Egypt, Cairo, Giza) Форма: гладкая, наклон: 53.12° Материал: , камень (известняк) Размеры, м: 215.3x215.3x143.5 Азимут, °: 0 Коментарий: M01, M02 000, 001, 002, 003 004, 005, Кат. N: PYReg003.GIZ03.LpsIX Название: Пирамида фараона Менкаура(Menkaure) Другие названия: Микерина (Menkaure), Лепсиус IX (Lepsius IX); Херу; Координаты: 29°58'21"N 31°07'42"E Ориентир: Египет, Каир, Гиза (Egypt, Cairo, Giza) Форма: гладкая, наклон: 51.72° Материал: , камень (известняк) Размеры, м: 102.2x104.6x65.5 Азимут, °: 0 Коментарий: M01, M02 000, 001, 002, 003, 004, 005, 006, 007, 008, 009, 010, 011, 012, 013, 014, 015, 016, 017, 018, Кат. N: PYReg004.GIZ04.LpsV Название:Пирамида царицы Хетепхерес I (Hetepheres I) фараона Хеопса. Другие названия: Царица Хетепхерес I (Queen Hetepheres I) ; G I-a; Лепсиус V (Lepsius V); Координаты: 29°58'43.80"N, 31° 8'10.23"E Ориентир: Египет, Каир, Гиза (Egypt, Cairo, Giza) Форма: гладкая, наклон: 51.72° Материал: , камень Размеры, м: 47.5x47.5x30.1(?) Азимут, °: 0 Коментарий: M01, M02 000, 001, 002, 003, 004, 005, 006, 007, 008, 009, Кат. -

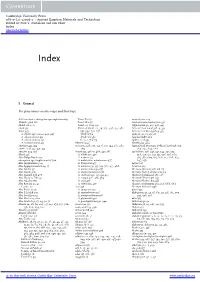

I General for Place Names See Also Maps and Their Keys

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12098-2 - Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology Edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw Index More information Index I General For place names see also maps and their keys. AAS see atomic absorption specrophotometry Tomb E21 52 aerenchyma 229 Abbad region 161 Tomb W2 315 Aeschynomene elaphroxylon 336 Abdel ‘AI, 1. 51 Tomb 113 A’09 332 Afghanistan 39, 435, 436, 443 abesh 591 Umm el-Qa’ab, 63, 79, 363, 496, 577, 582, African black wood 338–9, 339 Abies 445 591, 594, 631, 637 African iron wood 338–9, 339 A. cilicica 348, 431–2, 443, 447 Tomb Q 62 agate 15, 21, 25, 26, 27 A. cilicica cilicica 431 Tomb U-j 582 Agatharchides 162 A. cilicica isaurica 431 Cemetery U 79 agathic acid 453 A. nordmanniana 431 Abyssinia 46 Agathis 453, 464 abietane 445, 454 acacia 91, 148, 305, 335–6, 335, 344, 367, 487, Agricultural Museum, Dokki (Cairo) 558, 559, abietic acid 445, 450, 453 489 564, 632, 634, 666 abrasive 329, 356 Acacia 335, 476–7, 488, 491, 586 agriculture 228, 247, 341, 344, 391, 505, Abrak 148 A. albida 335, 477 506, 510, 515, 517, 521, 526, 528, 569, Abri-Delgo Reach 323 A. arabica 477 583, 584, 609, 615, 616, 617, 628, 637, absorption spectrophotometry 500 A. arabica var. adansoniana 477 647, 656 Abu (Elephantine) 323 A. farnesiana 477 agrimi 327 Abu Aggag formation 54, 55 A. nilotica 279, 335, 354, 367, 477, 488 A Group 323 Abu Ghalib 541 A. nilotica leiocarpa 477 Ahmose (Amarna oªcial) 115 Abu Gurob 410 A. -

Who's Who in Ancient Egypt

Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Available from Routledge worldwide: Who’s Who in Ancient Egypt Michael Rice Who’s Who in the Ancient Near East Gwendolyn Leick Who’s Who in Classical Mythology Michael Grant and John Hazel Who’s Who in World Politics Alan Palmer Who’s Who in Dickens Donald Hawes Who’s Who in Jewish History Joan Comay, new edition revised by Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok Who’s Who in Military History John Keegan and Andrew Wheatcroft Who’s Who in Nazi Germany Robert S.Wistrich Who’s Who in the New Testament Ronald Brownrigg Who’s Who in Non-Classical Mythology Egerton Sykes, new edition revised by Alan Kendall Who’s Who in the Old Testament Joan Comay Who’s Who in Russia since 1900 Martin McCauley Who’s Who in Shakespeare Peter Quennell and Hamish Johnson Who’s Who in World War Two Edited by John Keegan Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Michael Rice 0 London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. © 1999 Michael Rice The right of Michael Rice to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

A Social and Religious Analysis of New Kingdom Votive Stelae from Asyut

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Display and Devotion: A Social and Religious Analysis of New Kingdom Votive Stelae from Asyut A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures by Eric Ryan Wells 2014 © Copyright by Eric Ryan Wells ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Display and Devotion: A Social and Religious Analysis of New Kingdom Votive Stelae from Asyut by Eric Ryan Wells Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Jacco Dieleman, Chair This dissertation is a case study and analysis of provincial religious decorum at New Kingdom Asyut. Decorum was a social force that restricted and defined the ways in which individuals could engage in material displays of identity and religious practice. Four-hundred and ninety-four votive stelae were examined in an attempt to identify trends and patters on self- display and religious practice. Each iconographic and textual element depicted on the stelae was treated as a variable which was entered into a database and statistically analyzed to search for trends of self-display. The analysis of the stelae revealed the presence of multiple social groups at Asyut. By examining the forms of capital displayed, it was possible to identify these social groups and reconstruct the social hierarchy of the site. This analysis demonstrated how the religious system was largely appropriated by elite men as a stage to engage in individual competitive displays of identity and capital as a means of reinforcing their profession and position in society and the II patronage structure. -

Historiografski Problemi Kronologije Staroegipatske Povijesti U Hrvatskim Povijesnim Znanostima I Nastavi Povijesti

Mladen Tomorad Filozofski fakultet u Zagrebu Pregledni članak UDK: 930.24(32):930(497.5) Historiografski problemi kronologije staroegipatske povijesti u hrvatskim povijesnim znanostima i nastavi povijesti U članku autor raspravlja različite probleme vezane uz upotrebu staroegipatske kro- nologije u povijesnim znanostima. Posebno se analizira pojam datacija te daje pregled raznih metoda vremenskog određenja za arheološke nalaze, staroegipatske kronologije i računanje vremena kod starih Egipćana, podjela na dinastije te povijesnih izvora na kojima se sama kronologija zasniva. U posebnom poglavlju autor daje pregled upo- trebe raznih kronologija u povijesnim znanostima u Hrvatskoj od sredine 19. stoljeća do danas te njene upotrebe u udžbenicima povijesti. U završnom dijelu članka autor donosi novu kronologiju staroegipatske povijesti koja se zasniva na rezultatima naj- novijih istraživanja te za koju smatra da bi se trebala isključivo upotrebljavati u svim budućim povijesnim djelima. Ključne riječi: datacija, računanje vremena, kronologija, metode datiranja, Stari Egipat, faraon, dinastija, povijesni izvori, kronološke tablice 1. Datacija i metode datiranja arheoloških ostataka Svaka osoba koja se bavila izučavanjem arheološke građe zna da je jedan od najte- žih koraka prilikom znanstvene analize i obrade svakog predmeta odrediti njegovu starost. To je osobito teško u slučajevima naših vrlo starih predmeta koji se čuvaju u pojedinim muzejskim zbirkama jer je kontekst njihova nalaza najčešće nepoznat te su oni u razne institucije često stigli putem brojnih posrednika. Što je datacija? Pojam datacija (lat. datatio) znači da se svaki predmet mora sta- viti u neki vremenski kontekst, odrediti njegova starost, odnosno staviti ga u neke vremenske granice. Samo određenje starosti nalaza prilikom arheoloških iskapanja može biti relativno i apsolutno. -

Source Index

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-11336-7 — The Ancient Egyptian Economy Brian Muhs Index More Information SOURCE INDEX Note : An n following a page number indicates a note. Archives Book 15, 29.1–2, 207 Archive of Amennakhte, 112 Book 15, 92.2, 196 Archive of Amenothes, 248 Book 17, 52.6, 236 Archive of Ananiah, 192 , 193 , 204 Herodotus Archive of Djekhy and Ituredj, 202 , 205 , Book II, 30, 196 , 197 , 208 208 – 209 Book II, 154, 197 Archive of gooseherds of Hou, 192 , 193 , 205 Book II, 157, 206 Archive of Horemsaef, 82 – 83 Book II, 158, 317 Archive of Inena, 105 , 116 Book II, 159, 195 Archive of Menches, 245 Book II, 161, 195 Archive of Mesi, 100 , 112 , 128 – 129 , 130 Book II, 161–162, 313n 167 Archive of Mibtahiah, 204 Book II, 161–163, 169 Archive of Milon, 199 , 226 , 243 Book II, 163, 197 Archive of Pefheryhesy, 200 – 201 , 203 Book II, 164–166, 197 – 198 Archive of Petiese, 204 – 205 Book II, 168, 198 , 313 n 167 Archive of Petubast, 147 – 148 , 161 , 169 Book II, 169, 197 Archive of Totoes, 248 Book II, 177, 151 – 152 , 184 Archive of Tsenhor, 201 , 203 , 205 Book II, 178, 186 , 208 Archive of Zenon, 226 – 227 , 245 , 247 Book II, 179, 186 , 208 Book II, 182, 195 – 196 Biblical Works Cited Book III, 12, 15, 160, 207 Chronicles Book III, 91, 194 , 197 2 Chronicles 12:1–12, 170 Book IV, 42, 208 2 Chronicles 35:20–25, 206 Book IX, 32, 198 Isaiah 37:9, 170 Book VII, 7, 207 Kings Book VII, 89–99, 196 1 Kings 14:25, 170 Jerome 2 Kings 19:9, 170 Commentariorum in Danielem, 11, 5, 2 Kings 23:29–30, 206 234 , 236 2 Kings 23:31–34, -

Cwiek, Andrzej. Relief Decoration in the Royal

Andrzej Ćwiek RELIEF DECORATION IN THE ROYAL FUNERARY COMPLEXES OF THE OLD KINGDOM STUDIES IN THE DEVELOPMENT, SCENE CONTENT AND ICONOGRAPHY PhD THESIS WRITTEN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. KAROL MYŚLIWIEC INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY FACULTY OF HISTORY WARSAW UNIVERSITY 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would have never appeared without help, support, advice and kindness of many people. I would like to express my sincerest thanks to: Professor Karol Myśliwiec, the supervisor of this thesis, for his incredible patience. Professor Zbigniew Szafrański, my first teacher of Egyptian archaeology and subsequently my boss at Deir el-Bahari, colleague and friend. It was his attitude towards science that influenced my decision to become an Egyptologist. Professor Lech Krzyżaniak, who offered to me really enormous possibilities of work in Poznań and helped me to survive during difficult years. It is due to him I have finished my thesis at last; he asked me about it every time he saw me. Professor Dietrich Wildung who encouraged me and kindly opened for me the inventories and photographic archives of the Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, and Dr. Karla Kroeper who enabled my work in Berlin in perfect conditions. Professors and colleagues who offered to me their knowledge, unpublished material, and helped me in various ways. Many scholars contributed to this work, sometimes unconsciously, and I owe to them much, albeit all the mistakes and misinterpretations are certainly by myself. Let me list them in an alphabetical order, pleno titulo: Hartwig