Grenada Chapter for Volcanic Hazards Atlas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phreatomagmatic Eruptions of 2014 and 2015 in Kuchinoerabujima Volcano Triggered by a Shallow Intrusion of Magma

Journal of Natural Disaster Science, Volume 37,Number 2,2016,pp67-78 Phreatomagmatic eruptions of 2014 and 2015 in Kuchinoerabujima Volcano triggered by a shallow intrusion of magma Nobuo Geshi1, Masato Iguchi2, and Hiroshi Shinohara1 1 Geological Survey of Japan, AIST 2 Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University, (Received:Sep 2, 2016 Accepted:Oct.28, 2016) Abstract The 2014 and 2015 eruptions of Kuchinoerabujima Volcano followed a ~15-year precursory activation of the hydrothermal system induced by a magma intrusion event. Continuous heat transfer from the degassing magma body heated the hydrothermal system and the increase of the fluid pressure in the hydrothermal system caused fracturing of the unstable edifice, inducing a phreatic explosion. The 2014 eruption occurred from two fissures that traced the eruption fissures formed in the 1931 eruption. The explosive eruption detonated the hydrothermally-altered materials and part of the intruding magma. The rise of fumarolic activities before the past two activities in 1931-35 and 1966-1980 also suggest activation of the hydrothermal system by magmatic intrusions prior to the eruption. The long-lasting precursory activities in Kuchinoerabujima suggest complex processes of the heat transfer from the magma to the hydrothermal system. Keywords: Kuchinoerabujima Volcano, phreatomagmatic eruption, hydrothermal system, magma intrusion 1. Introduction Phreatic eruptions are generally caused by the rapid extrusion of geothermal fluid from a hydrothermal system within a volcanic edifice (Barberi et al., 1992). Hydrothermal activities and phreatic eruptions are related to magmatic activities directly or indirectly, as the hydrothermal activities of a volcano are basically driven by heat from magma (Grapes et al., 1974). -

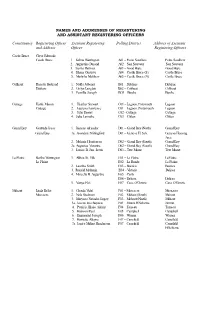

Names and Addresses of Registering and Assistant Registering Officers

NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF REGISTERING AND ASSISTANT REGISTERING OFFICERS Constituency Registering Officer Assistant Registering Polling District Address of Assistant and Address Officer Registering Officers Castle Bruce Cleve Edwards Castle Bruce 1. Kelma Warrington A01 – Petite Soufriere Petite Soufriere 2. Augustina Durand A02 – San Sauveur San Sauveur 3. Sasha Darroux A03 – Good Hope Good Hope 4. Shana Gustave A04 – Castle Bruce (S) Castle Bruce 5. Marlisha Matthew A05 – Castle Bruce (N) Castle Bruce Colihaut Rosette Bertrand 1. Nalda Jubenot B01 – Dublanc Dublanc Dublanc 2. Gislyn Langlais B02 – Colihaut Colihaut 3. Fernillia Joseph BO3 – Bioche Bioche Cottage Hartie Mason 1. Heather Stewart C01 – Lagoon, Portsmouth Lagoon Cottage 2. Laurena Lawrence C01 – Lagoon ,Portsmouth Lagoon 3. Julie Daniel C02 - Cottage Cottage 4. Julia Lamothe C03 – Clifton Clifton Grand Bay Gertrude Isaac 1. Ireneus Alcendor D01 – Grand Bay (North) Grand Bay Grand Bay 1a. Avondale Shillingford D01 – Geneva H. Sch. Geneva Housing Area 2. Melanie Henderson D02 – Grand Bay (South) Grand Bay 2a. Augustus Victorine D02 – Grand Bay (South) Grand Bay 3. Louise B. Jno. Lewis D03 – Tete Morne Tete Morne La Plaine Bertha Warrington 1. Althea St. Ville E01 – La Plaine LaPlaine La Plaine E02 – La Ronde La Plaine 2. Laurina Smith E03 – Boetica Boetica 3. Ronald Mathurin E04 - Victoria Delices 4. Marcella B. Augustine E05 – Carib E06 – Delices Delices 5. Vanya Eloi E07 – Case O’Gowrie Case O’Gowrie Mahaut Linda Bellot 1. Glenda Vidal F01 – Massacre Massacre Massacre 2. Nola Stedman F02 – Mahaut (South) Mahaut 3. Maryana Natasha Lugay F03- Mahaut (North) Mahaut 3a. Josette Jno Baptiste F03 – Jimmit H/Scheme Jimmit 4. -

Guadeloupedos 2018 - 2019 Www Guadeloupe Best Of

2018 2019 2018 - 2019 English edition best of guadeloupe Dos best of guadeloupe www.petitfute.uk PUBLISHING Collection Directors and authors: Dominique AUZIAS and Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE Welcome to Authors: Nelly DEFLISQUESTE, SIMAX CONSULTANT-Christine MOREL, Patricia BUSSY, Johann CHABERT, Juliana HACK, Guadeloupe! Faubert BOLIVAR, Yaissa ARNAUD BOLIVAR, Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE, Dominique AUZIAS and alter Publishing director: Stephan SZEREMETA Of all the "Lesser Antilles", the Guadeloupean Publishing team (France): Elisabeth COL, archipelago is the most surprising when it comes Silvia FOLIGNO, Tony DE SOUSA, Agnès VIZY to the variety of landscapes. A seaside destination Publishing team (World): Caroline MICHELOT, par excellence, Grande-Terre, with its crystal-clear Morgane VESLIN, Pierre-Yves SOUCHET, Jimmy POSTOLLEC, Elvane SAHIN water beaches and blue lagoons, delights lovers of sunbathing. In the coral funds, diving spots are STUDIO multiple, and even beginners, with mask and snorkel, Studio Manager: Sophie LECHERTIER assisted by Romain AUDREN can enjoy the underwater spectacle. But Mother Layout: Julie BORDES, Sandrine MECKING, Nature reserves many other surprises. Large and Delphine PAGANO and Laurie PILLOIS small wild coves for adventurers, lush tropical forest, Pictures and mapping management: vertiginous waterfalls, rivers with refreshing waters, Anne DIOT and Jordan EL OUARDI volcanic land, high limestone plateaus, steep cliffs, WEB fragile and mysterious mangrove… A biodiversity Web Director: Louis GENEAU de LAMARLIERE promising -

Commonwealth of Dominica Office of Director of Audit Report of The

Commonwealth of Dominica Office of Director of Audit Report of the DIRECTOR OF AUDIT on the AUDIT OF THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS For the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 2013 CONTENTS Letter………………………………………………………..……………… 1 Certificate of the Director of Audit ……………………………………… 2 Statement of Assets and Liabilities…………………………………….. 3 Statement of External Debt ……………………………………… 4 Annual Abstract Account of Receipts and Payments ………………... 6 Notes to the Financial Statements……………………………………… 9 CHAPTER 1 Introduction………………………………………………………………... 19 Audit Mandate ……………………………………………………………. 19 Audit Approach……………………………………………………………. 21 Submission of Accounts………………………………………………….. 23 Reporting Process and Practices ………………… ……………………. 23 Smart Stream System……………………………………………………. 23 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………….. 23 CHAPTER 2 Annual Abstract Account of Revenue and Expenditure Revenue………………………………………………………........ 24 Expenditure………………………………………………………… 30 Statement of Public Debt………………………………………………..... 34 1 CHAPTER 3 Contingencies Fund Advance Warrant……………………………….. 35 Travel Advances ………….………………………………………………. 36 Virement Warrants………………………………………………………… 37 Dishonoured Cheques ………………………………………………….. 37 Arrears of Revenue ……………………………………………............... 38 Overtime……………………………………………………………………. 39 CHAPTER 4 Government Capital Projects……………………………………………… 40 CHAPTER 5 Special Audits………………………………………………………………. 61 END 2 OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR OF AUDIT TREASURY BUILDING ROSEAU COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA August 26, 2016 The Honourable Minister for Finance Financial Complex Roseau COMMONWEALTH -

Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems Gaps Report: Dominica, 2018

MULTI-HAZARD EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS GAPS ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA, 2018 MULTI-HAZARD EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS GAPS REPORT: DOMINICA, 2018 Led by Dominica Emergency Management Organisation Director Mr. Fitzroy Pascal Author Gelina Fontaine (Local Consultant) National coordination John Walcott (UNDP Barbados & OECS) Marlon Clarke (UNDP Barbados & OECS) Regional coordination Janire Zulaika (UNDP – LAC) Art and design: Beatriz H.Perdiguero - Estudio Varsovia This document covers humanitarian aid activities implemented with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Union, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. UNDP CDEMA IFRC ECHO United Nations Caribbean Disaster International Federation European Civil Protection Development Emergency of the Red Cross and and Humanitarian Programme Management Agency Red Crescent Societies Aid Operations Map of Dominica. (Source Jan M. Lindsay, Alan L. Smith M. John Roobol and Mark V. Stasiuk Dominica, Chapter for Volcanic Hazards Atlas) CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 2 2. Dominica Context 6 3. MHEWS Capacity and Assets 16 4. MHEWS Specific Gaps As It Relates To International Standards 24 27 4.1 Disaster Risk Knowledge Gaps DOMINICA OF 4.2 Disaster Risk Knowledge Recommendations 30 4.3 Gaps in detection, monitoring, analysis and forecasting 31 4.4 Recommendations for detection, monitoring, analysis and forecasting 35 4.5 Warning Dissemination and Communication Gaps 36 4.6 Recommendations for Warning Dissemination and Communication 38 4.7 Gaps in Preparedness and Response Capabilities 39 4.8 Recommendations for Preparedness and Response Capabilities 14 5. -

Volume 13: 2018-19

TRAIL SIX UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF GEOGRAPHY VOLUME 13: 2018-19 Geography Students’ Association Department of Geography University of British Columbia 2 TRAIL SIX EDITORIAL BOARD 2018/19 Editor-in-Chief: Nigel Tan Editors: Alex Briault, Andrew Butt, Jose Carvajal, Jamie Chan, Richie Chan, Phoebe DeLucco, Carly Gardner, Nicholas Hare, Nicolo Jimenez, Maya Korbynn, Angela Liu, Danielle Main, Joshua Medicoff, Aaron Obedkoff, Elana Shi, Deanna Shrimpton, Maddy Stewart, Eva Streitz, & Cass Torres Layout & Design: Danielle Main Faculty Acknowledgements: Dr. Marwan Hassan (Department Head), Dr. Loch Brown, Dr. Michelle Daigle, Dr. Jessica Dempsey, Dr. Simon Donner, Dr. Sally Hermansen, Dr. Nina Hewitt, Dr. Philippe LeBillion, Dr. Jamie Peck, Dr. Juanita Sundberg, & Dr. Elvin Wyly Land Acknowledgment: We acknowledge that UBC’s Point Grey Campus is located on the traditional, ancestral, unceded territory of the Musqueam people. The land it is situated on has always been a place of learning for the Musqueam people, who for millennia have passed on in their culture, history, and traditions from one generation to the next on this site. Special Thanks to: UBC Department of Geography & Geography Students’ Association All correspondence concerning Trail Six should be addressed to: Trail Six: Undergraduate Journal of Geography Department of Geography University of British Columbia 1984 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada, V6T 1Z2 Email: [email protected] Website: trailsix.geog.ubc.ca © UBC Geography Students’ Association, March 2019 Cover photograph: © Mika Yasutake The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the individual authors. 3 Contents FOREWORD . 4 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR . 5 Catastrophe of Nevado de Ruiz Alex Briault . 6 Organizing Logics in Climate Change Policy: Neoliberalism and Deflection Through Demand-Side Solutions Abdo Souraya . -

Mapaction Brochure

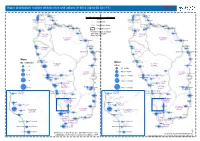

Potable water status: Litres delivered in last five days and remaining days supplies Up to 8 October 2017 Potable Water status: litres delivered in last 5 days and remaining days supplies (up to 08 Oct 2017) All settlements within an 'Operational' Water Dominica 0 2.5 5 10 15 MA626 v1 Capuchin Penville Capuchin Service Area are removed from this representation L'Autre Clifton Bord Kilometers as their demands 'should' be being met. In 2017, Hurricanes Cottage & Cocoyer Vieille !( Settlements Calculation of water remaining based on the Toucari & Morne Cabrit Case population x 7.5 litres per person per day Irma and Maria Savanne Paille Savanne Paille & Tantan & Tantan Moore Park Thibaud Major/Minor Road Thibaud devastated parts of Estate Moore Park Estate Calibishie Anse de Mai Bense Parish Boundaries Bense & Hampstead the Caribbean. Dos & Hampstead Woodford Dos D'Ane Lagon & De D'Ane Hill Woodford Hill La Rosine Borne Borne MapAction Portsmouth Glanvillia Wesley Wesley ST. JOHN responded quickly ST. JOHN Picard 6561 PPL and in numbers, 6561 PPL ST. ANDREW ST. ANDREW producing hundreds Marigot & 9471 PPL 9471 PPL Marigot & Concord of maps, including Concord this one showing the Atkinson Dublanc & Bataka Dublanc Atkinson & Bataka urgent need for water Bioche ST. PETER Bataka Bioche Bataka in Dominica, which 1430 PPL Water (Days) ST. PETER 1430 PPL Salybia & St. Cyr & Gaulette & Sineku took a direct hit from St. Cyr Remaining days St. Cyr Colihaut Colihaut Category 5 Hurricane Gaulette (! < 1 day Gaulette Maria. MapAction Sineku (! 1 - 2 days Sineku volunteers were Coulibistrie Coulibistrie (! 2 - 3 days Morne Rachette amongst the first ST. -

Processes Culminating in the 2015 Phreatic Explosion at Lascar Volcano, Chile, Evidenced by Multiparametric Data

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 20, 377–397, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-20-377-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Processes culminating in the 2015 phreatic explosion at Lascar volcano, Chile, evidenced by multiparametric data Ayleen Gaete1, Thomas R. Walter1, Stefan Bredemeyer1,2, Martin Zimmer1, Christian Kujawa1, Luis Franco Marin3, Juan San Martin4, and Claudia Bucarey Parra3 1GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany 2GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, 24148 Kiel, Germany 3Observatorio Volcanológico de Los Andes del Sur (OVDAS), Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería (SERNAGEOMIN), Temuco, Chile 4Physics Science Department, Universidad de la Frontera, Casilla 54-D, Temuco, Chile Correspondence: Ayleen Gaete ([email protected]) Received: 13 June 2019 – Discussion started: 25 June 2019 Accepted: 5 December 2019 – Published: 4 February 2020 Abstract. Small steam-driven volcanic explosions are com- marole on the southern rim of the Lascar crater revealed a mon at volcanoes worldwide but are rarely documented or pronounced change in the trend of the relationship between monitored; therefore, these events still put residents and the CO2 mixing ratio and the gas outlet temperature; we tourists at risk every year. Steam-driven explosions also oc- speculate that this change was associated with the prior pre- cur frequently (once every 2–5 years on average) at Lascar cipitation event. An increased thermal anomaly inside the ac- volcano, Chile, where they are often spontaneous and lack tive crater as observed in Sentinel-2 images and drone over- any identifiable precursor activity. -

Demographic Statistics No.5

COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA DE,MOGRAP'HIC STAT~STICS NO.5 2008 ICENTRAL STATISTICAL OFFICE, Ministry of Finance and Social Security, Roseau, Dominica. Il --- CONTENTS PAGE Preface 1 Analysis ll-Xlll Explanatory Notes XIV Map (Population Zones) XV Map (Topography) xvi TABLES Non-Institutional Population at Census Dates (1901 - 2001) 1 2 Non-Institutional Population, Births and Deaths by Sex At Census Years (1960 - 200I) 2 3 Non-Institutional Population by Sex and Five Year Age Groups (1970,1981,1991, and 2001) 3 4 Non-Institutional Population By Five Year Age Groups (1970,1981, 1991 and 2001) 4 5 Population By Parishes (1946 - 200 I) 5 6 Population Percentage Change and Intercensal Annual Rate of Change (1881 - 200 I) 6 7 Population Density By Land Area - 200I Census compared to 1991 Census 7 8 Births and Deaths by Sex (1990 - 2006) 8 9 Total Population Analysed by Births, Deaths and Net Migration (1990 - 2006) 9 10 Total Persons Moving into and out ofthe Population (1981 -1990, 1991 - 2000 and 2001 - 2005) 10 II Number ofVisas issued to Dominicans for entry into the United States of America and the French Territories (1993 - 2003) 11 12 Mean Population and Vital Rates (1992 - 2006) 12 13 Total Births by Sex and Age Group ofMother (1996 - 2006) 13 14 Total Births by Sex and Health Districts (1996 - 2006) 14 15 Total Births by Age Group ofMother (1996 - 2006) 15 15A Age Specific Fertility Rates ofFemale Population 15 ~ 44 Years not Attending School 1981. 1991 and 2001 Census 16 16 Age Specific Birth Rates (2002 - 2006) 17 17 Basic Demographic -

NAMES on DOMINICA Dominica Was Occupied Successively by Speakers

NAMES ON DOMINICA BY DOUGLAS TAYLOR *) Dominica was occupied successively by speakers of Arawakan, Cariban, French, and English dialects, all of which have left their mark in place-names, as well as in the names of local flora and fauna. African influence appears to have been minimal in this respect. The Arawakan language of the island's early in- habitants survived that of the Carib invaders (from which, how- ever, many words were borrowed), but the last native speaker died about 1920. Two languages are spoken today: English and a dialect of French Creole. The former, being the language of prestige, is usually employed by the more socio-economically privileged minority, the latter by the peasant majority, few of whom know much English. However, members of the first class often resort to Creole in their more intimate relations; while many among even the poorest peasants may be heard addressing young children in what they believe to be English, and chiding them for speaking "Patois". One curious result of this situation is that not only local fruits, trees, fishes, birds, e/c., but also many places — probably most of those that have ever been recorded in writing — have two (or more) names, the one em- ployed in Creole and the other in English speech. So, for example, Grande Anse or Portsmouth is the island's second largest town, Charlotteville or New Town is a suburb of the capital Roseau (which has no other name), Cachacrou or Scots Head is a peninsula at the island's southwestern extremity, Cachibona of Clyde is one of its rivers. -

© 2009 by Richard Vanderhoek. All Rights Reserved

© 2009 by Richard VanderHoek. All rights reserved. THE ROLE OF ECOLOGICAL BARRIERS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF CULTURAL BOUNDARIES DURING THE LATER HOLOCENE OF THE CENTRAL ALASKA PENINSULA BY RICHARD VANDERHOEK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2009 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor R. Barry Lewis, Chair Professor Stanley H. Ambrose Professor Thomas E. Emerson Professor William B. Workman, University of Alaska ABSTRACT This study assesses the capability of very large volcanic eruptions to effect widespread ecological and cultural change. It focuses on the proximal and distal effects of the Aniakchak volcanic eruption that took place approximately 3400 rcy BP on the central Alaskan Peninsula. The research is based on archaeological and ecological data from the Alaska Peninsula, as well as literature reviews dealing with the ecological and cultural effects of very large volcanic eruptions, volcanic soils and revegetation of volcanic landscapes, and northern vegetation and wildlife. Analysis of the Aniakchak pollen and soil data show that the pyroclastic flow from the 3400 rcy BP eruption caused a 2500 km² zone of very low productivity on the Alaska Peninsula. This "Dead Zone" on the central Alaska Peninsula lasted for over 1000 years. Drawing on these data and the results of archaeological excavations and surveys throughout the Alaska Peninsula, this dissertation examines the thesis that the Aniakchak 3400 rcy BP eruption created a massive ecological barrier to human interaction and was a major factor in the separate development of modern Eskimo and Aleut populations and their distinctive cultural traditions. -

Water Distribution: Number of Deliveries and Volume in Litres (Up to 08 Oct '17) MA621 V2

Water distribution: number of deliveries and volume in litres (up to 08 Oct '17) MA621 v2 CapuchinDemetrie & Le Haut & Delaford CapuchinDemetrie & Le Haut & Delaford Penville 0 1.5 3 6 9 12 Penville Clifton L'Autre Bord Clifton L'Autre Bord Cottage & Cocoyer Vieille Case Kilometers Cottage & Cocoyer Vieille Case Toucari & Morne Cabrit !( Toucari & Morne Cabrit Savanne Paille & Tantan Settlements Savanne Paille & Tantan Moore Park EstaTtehibaud Moore Park EstaTtehibaud Paix Bouche Anse de Mai Major/Minor Road Paix Bouche Anse de Mai Belmanier Bense & HampsteaCd alibishie Belmanier Bense & HampsteaCd alibishie Dos D'Ane Woodford Hill Dos D'Ane Woodford Hill Lagon & De La Rosine Borne Parish Boundaries Lagon & De La Rosine Borne Portsmouth Portsmouth Population figure displayed Glanvillia Wesley Glanvillia Wesley ST. JOHN after Settlement and ST. JOHN Picard Picard 6561 PPL Parish Names 6561 PPL ST. ANDREW ST. ANDREW 9471 PPL Marigot & Concord 9471 PPL Marigot & Concord Dublanc Atkinson & Bataka Dublanc Atkinson & Bataka Bioche ST. PETER Bataka Bioche Bataka 1430 PPL ST. PETER Salybia & St. Cyr & Gaulette & Sineku 1430 PPL Salybia & St. Cyr & Gaulette & Sineku St. Cyr St. Cyr Colihaut Colihaut Gaulette Gaulette Sineku Sineku Water Coulibistrie Coulibistrie Morne Rachette Water Morne Rachette No. deliveries ST. JOSEPH ST. JOSEPH 5637 PPL Castle Bruce Litres Castle Bruce 1 - 2 Salisbury Salisbury 5637 PPL 13 - 8000 3 - 4 Belles Belles ST. DAVID 8001 - 16000 ST. DAVID 6043G PooPdL Hope & Dix Pais & Tranto 6043G PooPd LHope & Dix Pais & Tranto 5 - 6 St. Joseph Village Layou Valley Area St. Joseph Village Layou Valley Area San Sauveur 16001 - 24000 San Sauveur Layou Village Layou Village Warner Petite Soufriere Warner Petite Soufriere Tarou Tarou 7 - 8 Pond Casse 24001 - 32000 Pond Casse Campbell & Bon Repos Campbell & Bon Repos Jimmit Jimmit Mahaut ST.