A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Defence of the Alterfactual in Historical Analysis Darlington, RR

In defence of the alterfactual in historical analysis Darlington, RR Title In defence of the alterfactual in historical analysis Authors Darlington, RR Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/10094/ Published Date 2006 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. In Defence of the Alterfactual in Historical Analysis In recent years a small number of so-called ‘counterfactual’ or ‘what-if’ historical books, which ask us to imagine what would have happened if events in the past had turned out differently than they did, have been published. They have stimulated an important, albeit not entirely new, methodological debate about issues and questions which are (or should be) of central relevance to the work of socialist historians, and which such historians need to engage with and contribute towards. This brief discussion article attempts to do this by presenting one particular Marxist viewpoint, with the hope and expectation others (hopefully supportive but possibly critical of the argument presented here) will follow. In the process, it examines the past use (and abuse) of the counterfactual within historical analysis, presents an argument for the validity of a refined and renamed ‘alterfactual’ approach, and examines the use of such an alterfactual approach to the British miners’ strike of 1984-5. -

Common Place: Rereading 'Nation' in the Quoting Age, 1776-1860 Anitta

Common Place: Rereading ‘Nation’ in the Quoting Age, 1776-1860 Anitta C. Santiago Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Anitta C. Santiago All rights reserved ABSTRACT Common Place: Rereading ‘Nation’ in the Quoting Age, 1776-1860 Anitta C. Santiago This dissertation examines quotation specifically, and intertextuality more generally, in the development of American/literary culture from the birth of the republic through the Civil War. This period, already known for its preoccupation with national unification and the development of a self-reliant national literature, was also a period of quotation, reprinting and copying. Within the analogy of literature and nation characterizing the rhetoric of the period, I translate the transtextual figure of quotation as a protean form that sheds a critical light on the nationalist project. This project follows both how texts move (transnational migration) and how they settle into place (national naturalization). Combining a theoretical mapping of how texts move and transform intertextually and a book historical mapping of how texts move and transform materially, I trace nineteenth century examples of the culture of quotation and how its literary mutability both disrupts and participates in the period’s national and literary movements. In the first chapter, I engage scholarship on republican print culture and on republican emulation to interrogate the literary roots of American nationalism in its transatlantic context. Looking at commonplace books, autobiographies, morality tales, and histories, I examine how quotation as a practice of memory impression functions in national re-membering. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

King George VI Wikipedia Page

George VI of the United Kingdom - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 10/6/11 10:20 PM George VI of the United Kingdom From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from King George VI) George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom George VI and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death. He was the last Emperor of India, and the first Head of the Commonwealth. As the second son of King George V, he was not expected to inherit the throne and spent his early life in the shadow of his elder brother, Edward. He served in the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force during World War I, and after the war took on the usual round of public engagements. He married Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon in 1923, and they had two daughters, Elizabeth and Margaret. George's elder brother ascended the throne as Edward VIII on the death of their father in 1936. However, less than a year later Edward revealed his desire to marry the divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson. British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin advised Edward that for political and Formal portrait, c. 1940–46 religious reasons he could not marry Mrs Simpson and remain king. Edward abdicated in order to marry, and George King of the United Kingdom and the British ascended the throne as the third monarch of the House of Dominions (more...) Windsor. Reign 11 December 1936 – 6 February On the day of his accession, the parliament of the Irish Free 1952 State removed the monarch from its constitution. -

Papers of Sir Edmund Barton Ms51

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA PAPERS OF SIR EDMUND BARTON MS51 Manuscript Collection 1968-70, 1996 and last amended 2001 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview 3 Biographical Note 6 Related Material 8 Microfilms 9 Series Description 10 Series 1: Correspondence 1827-1921 10 Series 2: Diaries, 1869, 1902-03 39 Series 3: Personal documents 1828-1939, 1844 39 Series 4: Commissions, patents 1891-1903 40 Series 5: Speeches, articles 1898-1901 40 Series 6: Papers relating to the Federation Campaign 1890-1901 41 Series 7: Other political papers 1892-1911 43 Series 8: Notes, extracts 1835-1903 44 Series 9: Newspaper cuttings 1894-1917 45 Series 10: Programs, menus, pamphlets 1883-1910 45 Series 11: High Court of Australia 1903-1905 46 Series 12: Photographs (now in Pictorial Section) 46 Series 13: Objects 47 Name Index of Correspondence 48 Box List 61 2 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 Overview This is a Guide to the Papers of Sir Edmund Barton held in the Manuscript Collection of the National Library of Australia. As well as using this guide to browse the content of the collection, you will also find links to online copies of collection items. Scope and Content The collection consists of correspondence, personal papers, press cuttings, photographs and papers relating to the Federation campaign and the first Parliament of the Commonwealth. Correspondence 1827-1896 relates mainly to the business and family affairs of William Barton, and to Edmund's early legal and political work. Correspondence 1898-1905 concerns the Federation campaign, the London conference 1900 and Barton's Prime Ministership, 1901-1903. -

Literature in the Louisiana Plantation Home Prior to 1861: a Study in Literary Culture

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1937 Literature in the Louisiana Plantation Home Prior to 1861: A Study in Literary Culture. Walton R. Patrick Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Patrick, Walton R., "Literature in the Louisiana Plantation Home Prior to 1861: A Study in Literary Culture." (1937). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7803. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7803 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the master^ and doctor*s degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Library are available for inspection* Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author* Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission# Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work* A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above res trictions * LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY LITERATURE IN THE LOUISIANA PLANTATION HOME PRIOR TO 1861 A STUDY IN LITERARY CULTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY AND AGRICULTURAL AND MECHANICAL COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH Walton Richard Patrick M. -

The Man Who Enriched – and Robbed – the Tories

Parliamentary History,Vol. 40, pt. 2 (2021), pp. 378–390 The Man Who Enriched – and Robbed – the Tories ALISTAIR LEXDEN House of Lords Horace Farquhar, financier, courtier and politician, was a man without a moral compass. He combined ruthlessness and dishonesty with great charm. As a Liberal Unionist MP in the 1890s, his chief aim was to get a peerage, for which he paid handsomely. He exploited everyone who came his way to increase his wealth and boost his social position, gaining an earldom from Lloyd George, to whose notorious personal political fund he diverted substantial amounts from the Conservative Party, of which he was treasurer from 1911 to 1923, the first holder of that post. The Tories’ money went into his own pocket as well. During these years, he also held senior positions at court, retaining under George V the trust of the royal family which he had won under Edward VII.By the time of his death in 1923,however,his wealth had disappeared,and he was found to be bankrupt. He was a man of many secrets. They have been probed and explored, drawing on such material relating to his scandalous career as has so far come to light. Keywords: Conservative Party; financial corruption; homosexuality; Liberal Unionist Party; monarchy; royal family; sale of honours 1 Horace Brand Farquhar (1844–1923), pronounced Farkwer, 1st and last Earl Farquhar, of St Marylebone,was one of the greatest rogues of his time,a man capable of almost any misdeed or sin short of murder (and it is hard to feel completely confident that he would have drawn thelineeventhere).1 He had three great loves: money, titles and royalty. -

Publicity Material List

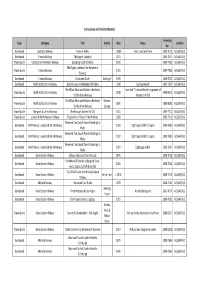

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

The Great Western Railway and the Celebration of Englishness

THE GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY AND THE CELEBRATION OF ENGLISHNESS D.Phil. RAILWAY STUDIES I.R.S. OCTOBER 2000 THE GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY AND THE CELEBRATION OF ENGLISHNESS ALAN DAVID BENNETT M.A. D.Phil. RAILWAY STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF YORK INSTITUTE OF RAILWAY STUDIES OCTOBER 2000 ABSTRACT This thesis identifies the literary work of the Great Western Railway as marking a significant contribution to the discourse of cultural representation over the first four decades of the twentieth century and particularly so for the inter-war era. The compa- ny's work is considered in the context of definitive and invariably complex cultural per- spectives of its day, as mediated through the examination of the primary literature, com- pany works and other related sources, together with the historiographical focus of latter- day analysis. G.W.R. literary perspectives - historical, political, commercial-industrial and aesthetic - are thus compared and contrasted with both rival and convergent repre- sentations and contextualised within the process of historical development and ideolog- ical differentiations. Within this perspective of inter-war society, the G.W.R. literature is considered according to four principal themes: the rural-traditional representation and related his- torical-cultural identification in the perceived sense of inheritance and providential mis- sion; the company's extensive industrial interests, wherein regional, national and inter- national perspectives engaged a commercial-cultural construction of Empire; the 'Ocean Coast' imagery - the cultural formulation of the seashore in terms of a taxonomy of landscapes and resorts according to the structural principles of protocol, expectation and clientele and, finally, that of Anglo-Saxon-Celtic cultural characterisations with its agenda of ethnicity and gender, central in the context of this work to the definition of Englishness and community. -

Robert Harborough Sherard Collection MS 1047

University Museums and Special Collections Service Robert Harborough Sherard Collection MS 1047 The collection contains around 650 personal and business letters written to Sherard 1908-1943 by over 200 correspondents, including Lord Alfred Douglas and Robert Ross. There are copies of three letters from Oscar Wilde. In addition, there are around 200 letters written by Sherard 1906-1937 (mainly copies), around 70 letters to Alice Muriel Fiddian, Sherard's third wife, and 35 other items of correspondence. There are two of Sherard's diaries, one covering the period July 22 - December 31 1934 and consisting chiefly of a record of letters written, and the other relating to Oscar Wilde twice defended and covering the period 1933-1939. The collection also contains newspaper cuttings 1887-1943, mainly relating to Sherard's work. There are around 60 typescripts and manuscripts of his articles, novels and short stories. Other items include photographs and prints of people and places c. 1920-1939, two family wills, documents relating to legal disputes, notes and other sundry papers. The collection is supported by around 40 printed books by Sherard, plus pamphlets, periodicals and offprints containing his work. The Collection covers the year’s 1868-1957. The physical extent of the collection is 12 boxes and 3 oversize items. Introduction Robert Harborough Sherard was born in London on 3 December 1861, the fourth child of the Reverend Bennet Sherard Calcraft Kennedy. His father was the illegitimate son of the sixth and last Earl of Harborough and his mother, Jane Stanley Wordsworth, granddaughter of the poet. In 1880 he went up to New College, Oxford but after a quarrel with his father, who cut him off from the expected family inheritance, was forced to leave for financial reasons. -

LORD HOPETOUN Papers, 1853-1904 Reels M936-37, M1154

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT LORD HOPETOUN Papers, 1853-1904 Reels M936-37, M1154-56, M1584 Rt. Hon. Marquess of Linlithgow Hopetoun House South Queensferry Lothian Scotland EH30 9SL National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1973, 1980, 1983 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE John Adrian Louis Hope (1860-1908), 7th Earl of Hopetoun (succeeded 1873), 1st Marquess of Linlithgow (created 1902), was born at Hopetoun House, near Edinburgh. He was educated at Eton and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, but did not enter the Army. In 1883 he was appointed Conservative whip in the House of Lords and in 1885 was made a lord-in-waiting to Queen Victoria. In 1886 he married Hersey Moleyns, the daughter of Lord Ventry. In 1889 Lord Knutsford, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, appointed Hopetoun as Governor of Victoria and he held the post until March 1895. Although it was a time of economic depression, he entertained extravagantly, but his youthful enthusiasm and fondness for horseback tours of country districts won him considerable popularity. His term coincided with the first federation conferences and he supported the federation movement strongly. In 1895-98 Hopetoun was paymaster-general in the government of Lord Salisbury. In 1898 Joseph Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, offered him the post of Governor-General of Canada, but he declined. He was appointed Lord Chamberlain in 1898 and had a close association with members of the Royal Family. In July 1900 Hopetoun was appointed the first Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia. He arrived in Sydney on 15 December 1900 and his first task was to appoint the head of the new Commonwealth ministry. -

Life with Lloyd George

LIFE WITH LLOYD GEORGE Even today, more than thirty years after its appearance, Life with Lloyd George (1975), by A. J. Sylvester, Principal Private Secretary to David Lloyd George from 1923, remains a valuable and unique source of information for students of Lloyd George, his life and times – particularly the so-called ‘wilderness years’ of the last phase of his life – and for those interested in his family. Dr J. Graham Jones examines the preparation, publication and impact of the book, drawing on extracts from Sylvester’s diaries between 1931 and 1945. 28 Journal of Liberal History 55 Summer 2007 LIFE WITH LLOYD GEORGE lbert James Syl- an immensely privileged posi- immediate family did and said. vester (1889–1989) tion. By nature he was a com- Originally, Sylvester kept his served as Principal pulsive, habitual note taker, a diary in a group of relatively Private Secretary to practice much facilitated by his small notebooks with black David Lloyd George proficiency in shorthand. From covers, which he crammed Afrom the autumn of 1923 until about 1915 onwards he took to with shorthand. Only members Lloyd George’s death in March recording in some detail the of his closest family were fully 1945.1 A native of Harlaston in seminal, often momentous aware of the nature of their Staffordshire and the son of a events which he witnessed at contents and the secrets which relatively impoverished tenant close quarters. Sometimes he they contained. farmer, he perfected his short- kept a diary. He went to great The detail of the diary is hand and typing skills by attend- pains to record the moves which amazing.