A Case of Color Aberration in a Fire Salamander (Salamandra Salamandra) Larva

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zoology SYLLABUS 2016

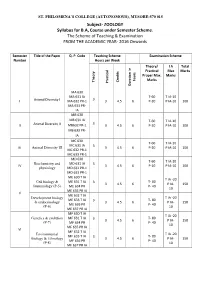

ST. PHILOMENA’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS), MYSORE-570 015 Subject- ZOOLOGY Syllabus for B.A, Course under Semester Scheme. The Scheme of Teaching & Examination FROM THE ACADEMIC YEAR- 2016 Onwards Semester Title of the Paper Q. P. Code Teaching Scheme Examination Scheme Number Hours per Week Theory/ I A Total Practical Max Marks Proper Max. Marks hours Marks Theory Credits Practical Duration in in Duration MA 630 MA 631 IA T-60 T IA-10 3 I Animal Diversity I MA 632 PR-1 3 4.5 6 P-20 P IA-10 100 MA 633 PR- IA MB 630 MB 631 IA T-60 T IA-10 3 II Animal Diversity II MB632 PR-1 3 4.5 6 P-20 P IA-10 100 MB 633 PR- IA MC 630 T-60 T IA-10 MC 631 IA 3 III Animal Diversity III 3 4.5 6 P-20 P IA-10 100 MC 632 PR-1 MC 633 PR-1 MD 630 T-60 T IA-10 Biochemistry and MD 631 IA 3 IV 3 4.5 6 P-20 P IA-10 100 physiology MD 632 PR-1 MD 633 PR-1 ME 630 T IA T IA -20 Cell biology & ME 631 T IA 3 T- 80 3 4.5 6 P IA- 150 Immunology (P-5) ME 634 PR P- 40 10 ME 635 PR IA V ME 632 T IA Development biology T IA -20 ME 633 T IA 3 T- 80 & endocrinology 3 4.5 6 P IA- 150 ME 636 PR P- 40 (P-6) 10 ME 637 PR IA MF 630 T IA T IA -20 Genetics & evolution MF 631 T IA 3 T- 80 3 4.5 6 P IA- 150 (P-7) MF 634 PR P- 40 10 MF 635 PR IA VI MF 632 T IA Environmental T IA -20 MF 633 T IA 3 T- 80 Biology & Ethnology 3 4.5 6 P IA- 150 MF 636 PR P- 40 (P-8) 10 MF 637 PR IA ST. -

The Origins of Chordate Larvae Donald I Williamson* Marine Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZB, United Kingdom

lopmen ve ta e l B Williamson, Cell Dev Biol 2012, 1:1 D io & l l o l g DOI: 10.4172/2168-9296.1000101 e y C Cell & Developmental Biology ISSN: 2168-9296 Research Article Open Access The Origins of Chordate Larvae Donald I Williamson* Marine Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZB, United Kingdom Abstract The larval transfer hypothesis states that larvae originated as adults in other taxa and their genomes were transferred by hybridization. It contests the view that larvae and corresponding adults evolved from common ancestors. The present paper reviews the life histories of chordates, and it interprets them in terms of the larval transfer hypothesis. It is the first paper to apply the hypothesis to craniates. I claim that the larvae of tunicates were acquired from adult larvaceans, the larvae of lampreys from adult cephalochordates, the larvae of lungfishes from adult craniate tadpoles, and the larvae of ray-finned fishes from other ray-finned fishes in different families. The occurrence of larvae in some fishes and their absence in others is correlated with reproductive behavior. Adult amphibians evolved from adult fishes, but larval amphibians did not evolve from either adult or larval fishes. I submit that [1] early amphibians had no larvae and that several families of urodeles and one subfamily of anurans have retained direct development, [2] the tadpole larvae of anurans and urodeles were acquired separately from different Mesozoic adult tadpoles, and [3] the post-tadpole larvae of salamanders were acquired from adults of other urodeles. Reptiles, birds and mammals probably evolved from amphibians that never acquired larvae. -

Amphibiaweb's Illustrated Amphibians of the Earth

AmphibiaWeb's Illustrated Amphibians of the Earth Created and Illustrated by the 2020-2021 AmphibiaWeb URAP Team: Alice Drozd, Arjun Mehta, Ash Reining, Kira Wiesinger, and Ann T. Chang This introduction to amphibians was written by University of California, Berkeley AmphibiaWeb Undergraduate Research Apprentices for people who love amphibians. Thank you to the many AmphibiaWeb apprentices over the last 21 years for their efforts. Edited by members of the AmphibiaWeb Steering Committee CC BY-NC-SA 2 Dedicated in loving memory of David B. Wake Founding Director of AmphibiaWeb (8 June 1936 - 29 April 2021) Dave Wake was a dedicated amphibian biologist who mentored and educated countless people. With the launch of AmphibiaWeb in 2000, Dave sought to bring the conservation science and basic fact-based biology of all amphibians to a single place where everyone could access the information freely. Until his last day, David remained a tirelessly dedicated scientist and ally of the amphibians of the world. 3 Table of Contents What are Amphibians? Their Characteristics ...................................................................................... 7 Orders of Amphibians.................................................................................... 7 Where are Amphibians? Where are Amphibians? ............................................................................... 9 What are Bioregions? ..................................................................................10 Conservation of Amphibians Why Save Amphibians? ............................................................................. -

About the Book the Format Acknowledgments

About the Book For more than ten years I have been working on a book on bryophyte ecology and was joined by Heinjo During, who has been very helpful in critiquing multiple versions of the chapters. But as the book progressed, the field of bryophyte ecology progressed faster. No chapter ever seemed to stay finished, hence the decision to publish online. Furthermore, rather than being a textbook, it is evolving into an encyclopedia that would be at least three volumes. Having reached the age when I could retire whenever I wanted to, I no longer needed be so concerned with the publish or perish paradigm. In keeping with the sharing nature of bryologists, and the need to educate the non-bryologists about the nature and role of bryophytes in the ecosystem, it seemed my personal goals could best be accomplished by publishing online. This has several advantages for me. I can choose the format I want, I can include lots of color images, and I can post chapters or parts of chapters as I complete them and update later if I find it important. Throughout the book I have posed questions. I have even attempt to offer hypotheses for many of these. It is my hope that these questions and hypotheses will inspire students of all ages to attempt to answer these. Some are simple and could even be done by elementary school children. Others are suitable for undergraduate projects. And some will take lifelong work or a large team of researchers around the world. Have fun with them! The Format The decision to publish Bryophyte Ecology as an ebook occurred after I had a publisher, and I am sure I have not thought of all the complexities of publishing as I complete things, rather than in the order of the planned organization. -

35 Finding of the Alpine Salamander (Salamandra Atra Laurenti, 1768; Salamandridae, Caudata) in the Nature Park Žumberak

HYLA VOL. 2011. No. 1 Str. 35-46 SHORT NOTE Finding of the Alpine salamander (Salamandra atra Laurenti, 1768; Salamandridae, Caudata) in the Nature Park Žumberak - Samoborsko gorje (NW Croatia) 1 2 3 NINA JERAN* , PETRA ĐURIĆ , KREŠIMIR ŽGANEC 1 Požarinje 69, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia, [email protected] 2 State Institute for Nature Protection, Trg Mažuranića 5, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 3 University of Zagreb, Faculty of Science, Rooseveltov trg 6, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia ABSTRACT This study confirms the presence of Alpine salamander (Salamandra atra) in the Nature Park Žumberak - Samoborsko gorje, where previously only one specimen was recorded in 1989. Species presence and distribution were investigated at ten different localities in stands of montane beech forest, during the vegetation season 2004. In July 2004 five individuals (four males and one female) of Alpine salamander were found in the virgin beech forest at site Kuta (about 900 m a.s.l.), during weather conditions characterized by heavy rain. This is the northernmost finding of the species in Croatia, as well as a confirmed disjunctive part of its areal in the Dinarids. Conservation measures for the species are proposed but for more precise conservation plan further research of species distribution and ecology is needed. Keywords: Alpine salamander, Salamandra atra, Nature Park Žumberak - Samoborsko gorje, distribution, amphibians 35 Alpine salamander (Salamandra atra) is a montane species occurring between 400 and 2,800 m a.s.l., but is usually found from 800 to 2,000 m a.s.l. (ARNOLD & BURTON, 1978). It inhabits mainly forests (beech, mixed deciduous and mixed deciduous-coniferous), but may also be found above the tree-line, in cool, damp alpine meadows, pastureland and other, slightly modified habitats. -

Rapid Enigmatic Decline Drives the Fire Salamander (Salamandra

Amphibia-Reptilia 34 (2013): 233-239 Rapid enigmatic decline drives the fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) to the edge of extinction in the Netherlands Annemarieke Spitzen-van der Sluijs1,4,∗, Frank Spikmans1, Wilbert Bosman1, Marnix de Zeeuw2, Tom van der Meij2, Edo Goverse1,MarjaKik3, Frank Pasmans4,AnMartel4 Abstract. In the Netherlands, the fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) is at the edge of its geographic range and is restricted to three small populations in the extreme south of the country. Despite the species being listed as ‘Endangered’ on the national Red List, the situation was considered to be stable. However, from 2008 onwards dead individuals were seen on more than one occasion. A sharp decline in numbers has been observed since 2010 (96%; P<0.01), but we were unable to attribute this to any known cause of amphibian decline, such as chytridiomycosis, ranavirus or habitat degradation. The present work describes this enigmatic decline, and we discuss these results in the context of possible causes. Keywords: enigmatic decline, local extinction, mortality, Salamandra salamandra, terrestrial salamanders. Introduction ranavirus (Daszak, Cunningham and Hyatt, 2003; Spitzen-van der Sluijs et al., 2010; Kik et Amphibians are experiencing declines globally, al., 2011) no specific decline has been observed. exemplified not only by population declines, However, the sudden, steep decline of the but also by range reductions and extinctions of fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra ter- some species (Houlahan et al., 2000; Stuart et restris) in the Netherlands is a new phe- al., 2004; IUCN, 2012), and they may be part nomenon. In the Netherlands, fire salamanders of a sixth major extinction event (Wake and live at the very edge of their distribution and Vredenburg, 2008), for which there is no single are confined to the old growth stages of de- cause (Blaustein et al., 2011; Hof et al., 2011). -

MAHS Care Sheet Master List *By Eric Roscoe Care Sheets Are Often An

MAHS Care Sheet Master List *By Eric Roscoe Care sheets are often an excellent starting point for learning more about the biology and husbandry of a given species, including their housing/enclosure requirements, temperament and handling, diet , and other aspects of care. MAHS itself has created many such care sheets for a wide range of reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates we believe to have straightforward care requirements, and thus make suitable family and beginner’s to intermediate level pets. Some species with much more complex, difficult to meet, or impracticable care requirements than what can be adequately explained in a one page care sheet may be multiple pages. We can also provide additional links, resources, and information on these species we feel are reliable and trustworthy if requested. If you would like to request a copy of a care sheet for any of the species listed below, or have a suggestion for an animal you don’t see on our list, contact us to let us know! Unfortunately, for liability reasons, MAHS is unable to create or publish care sheets for medically significant venomous species. This includes species in the families Crotilidae, Viperidae, and Elapidae, as well as the Helodermatidae (the Gila Monsters and Mexican Beaded Lizards) and some medically significant rear fanged Colubridae. Those that are serious about wishing to learn more about venomous reptile husbandry that cannot be adequately covered in one to three page care sheets should take the time to utilize all available resources by reading books and literature, consulting with, and working with an experienced and knowledgeable mentor in order to learn the ropes hands on. -

The Salamanders of Tennessee

Salamanders of Tennessee: modified from Lisa Powers tnwildlife.org Follow links to Nongame The Salamanders of Tennessee Photo by John White Salamanders are the group of tailed, vertebrate animals that along with frogs and caecilians make up the class Amphibia. Salamanders are ectothermic (cold-blooded), have smooth glandular skin, lack claws and must have a moist environment in which to live. 1 Amphibian Declines Worldwide, over 200 amphibian species have experienced recent population declines. Scientists have reports of 32 species First discovered in 1967, the golden extinctions, toad, Bufo periglenes, was last seen mainly species of in 1987. frogs. Much attention has been given to the Anurans (frogs) in recent years, however salamander populations have been poorly monitored. Photo by Henk Wallays Fire Salamander - Salamandra salamandra terrestris 2 Why The Concern For Salamanders in Tennessee? Their key role and high densities in many forests The stability in their counts and populations Their vulnerability to air and water pollution Their sensitivity as a measure of change The threatened and endangered status of several species Their inherent beauty and appeal as a creature to study and conserve. *Possible Factors Influencing Declines Around the World Climate Change Habitat Modification Habitat Fragmentation Introduced Species UV-B Radiation Chemical Contaminants Disease Trade in Amphibians as Pets *Often declines are caused by a combination of factors and do not have a single cause. Major Causes for Declines in Tennessee Habitat Modification -The destruction of natural habitats is undoubtedly the biggest threat facing amphibians in Tennessee. Housing, shopping center, industrial and highway construction are all increasing throughout the state and consequently decreasing the amount of available habitat for amphibians. -

Batrachochytrium Salamandrivorans Threat to the Iberian Urodele Hotspot

Journal of Fungi Article Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans Threat to the Iberian Urodele Hotspot Jaime Bosch 1,2,*, An Martel 3 , Jarrod Sopniewski 4 , Barbora Thumsová 1,2,5, Cesar Ayres 5, Ben C. Scheele 4,†, Guillermo Velo-Antón 6,7,† and Frank Pasmans 3,† 1 Biodiversity Research Institute (IMIB), University of Oviedo-Principality of Asturias-CSIC, 33600 Mieres, Spain; [email protected] 2 Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales-CSIC, 28006 Madrid, Spain 3 Wildlife Health Ghent, Department of Pathology, Bacteriology and Poultry Diseases, Ghent University, B9820 Merelbeke, Belgium; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (F.P.) 4 Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University, Canberra 2601, Australia; [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (B.C.S.) 5 Asociación Herpetologica Española, 28006 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 6 CIBIO/InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, 4485-661 Vairão, Portugal; [email protected] 7 Grupo GEA, Departamento de Ecoloxía e Bioloxía Animal, Universidade de Vigo, 36310 Vigo, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-6-777-724-02 † These author contributed equally to this paper. Abstract: The recent introduction of the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans into north- eastern Spain threatens salamander diversity on the Iberian Peninsula. We assessed the current epidemiological situation with extensive field sampling of urodele populations. We then sought to delineate priority regions and identify conservation units for the Iberian Peninsula by estimating the susceptibility of Iberian urodeles using laboratory experiments, evidence from mortality events Citation: Bosch, J.; Martel, A.; in nature and captivity and inference from phylogeny. -

The Evolution of Pueriparity Maintains Multiple Paternity in a Polymorphic Viviparous Salamander Lucía Alarcón‑Ríos 1*, Alfredo G

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The evolution of pueriparity maintains multiple paternity in a polymorphic viviparous salamander Lucía Alarcón‑Ríos 1*, Alfredo G. Nicieza 1,2, André Lourenço 3,4 & Guillermo Velo‑Antón 3* The reduction in fecundity associated with the evolution of viviparity may have far‑reaching implications for the ecology, demography, and evolution of populations. The evolution of a polygamous behaviour (e.g. polyandry) may counteract some of the efects underlying a lower fecundity, such as the reduction in genetic diversity. Comparing patterns of multiple paternity between reproductive modes allows us to understand how viviparity accounts for the trade-of between ofspring quality and quantity. We analysed genetic patterns of paternity and ofspring genetic diversity across 42 families from two modes of viviparity in a reproductive polymorphic species, Salamandra salamandra. This species shows an ancestral (larviparity: large clutches of free aquatic larvae), and a derived reproductive mode (pueriparity: smaller clutches of larger terrestrial juveniles). Our results confrm the existence of multiple paternity in pueriparous salamanders. Furthermore, we show the evolution of pueriparity maintains, and even increases, the occurrence of multiple paternity and the number of sires compared to larviparity, though we did not fnd a clear efect on genetic diversity. High incidence of multiple paternity in pueriparous populations might arise as a mechanism to avoid fertilization failures and to ensure reproductive success, and thus has important implications in highly isolated populations with small broods. Te evolution of viviparity entails pronounced changes in individuals’ reproductive biology and behaviour and, by extension, on population dynamics1–3. For example, viviparous species ofen show an increased parental invest- ment compared to oviparous ones because they produce larger and more developed ofspring that are protected from external pressures for longer periods within the mother 4–7. -

Fire Salamander Care Sheet

Fire salamander Care Sheet Common names: Fire Salamander It is believed that Fire Salamanders received their name by hiding in logs chopped for burning and then running out once the logs were placed on the fire. A myth grew up over this habit and our ancestors believed that they could not only withstand fire, but also that they lived in it. Scientific Name : Salamandra salamandra There are two main sub-species that are commonly found in the pet trade. These are Salamandra salamandra salamandra and Salamandra salamandra terrestis . S.s terrestis is sometimes called the Barred Fire Salamander. This care sheet will focus on these two species, but here is a list of some other Salamanders in the Salamandra salamandra family: Spotted Fire Salamander - Salamandra salamandra almanzoris Yellow Striped Fire Salamander - Salamandra salamandra fastuosa Bernadezi Fire Salamander - Salamandra salamandra bernadezi Near Eastern Fire Salamander - Samandra salamandra inframmaculata Portuguese Fire Salamander - Salamndra salamandra gallaica Corsican Fire Salamander - Salamandra salamandra corsica Los Barrios Fire Salamander - Salamandra salamandra longirostris Description Description: Depending on the type of Fire Salamander you have, their dorsum colours tend to be a glossy black with bright yellow blotches on their bodies. This yellow colouration varies between the species and is usually the way that the sub-species are differentiated from each other. They are quite stocky salamanders with long tails and visible parotoid glands in the area behind their protruding eyes. Size: Fire Salamanders generally grow to between 18 to 25cms (7-10inches) in length, but it is not unknown for them to reach 30cms (12inch) in some cases. -

The Central Texas Master Naturalist Newsletter December 2017

The Tracker The Central Texas Master Naturalist Newsletter December 2017 Mother Neff State Park Association Inside This Issue Chautauqua Fundraiser President’s Pen 3 -Rene Berkhoudt Mother Neff Chautauqua 1 The Mother Neff State Park Salado Sirena Fest 5 Association held its annual Chautauqua fundraiser this year Macroinvertebrates 7 on November 4th. You may well Autumn Youth Hikes 8 ask what the word ‘Chautauqua’ means. October Awards 9 The first Chautauqua, the New Holiday Cheer 11 York Chautauqua Assembly, was organized in 1874 at a campsite Scaling Down Nature 12 on the shores of Chautauqua Interesting Tidbits 13 Lake in New York State. Chautauqua lent its name to an adult education movement in the Calendar at a Glance United States that was highly popular in the late 19th and early December 5, hours due. 20th centuries. The Chautauqua was culture and entertainment for December 9, Mammoths in the the whole community, with speakers, teachers, musicians, entertainers, Moonlight— Mammoth National preachers, and specialists of the day. Former U.S. President Theodore Monument — Waco Roosevelt was quoted as saying that Chautauqua is "the most American December 12, 6:30 pm, 8th thing in America". The Chautauqua began to decline as a public forum Annual CTMN Holiday Party— in the 1920s in part due to the introduction of radio broadcasting. Zoe Rascoe’s House December 16, Winter Solstice — Chapter Motto Cave Without a Name—Boerne Earth Day, Continued on page 14... Every Day The Mother Neff State Park Association Chautauqua was a celebration of autumn and of all the wonderful things this beautiful park has to offer and featured a variety of activities, demonstrations and displays from diverse groups; such as the Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th and 10th U.S.