Food, Memory, Community: Kerala As Both 'Indian Ocean'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Anjali James and Rael Memnon Natural Beauty of Jammu and Kashmir Jammu and Kashmir

India Maddhya Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, and Kerala By Anjali James and Rael Memnon Natural Beauty of Jammu and Kashmir Jammu and Kashmir Location: Northern Indian Subcontinent Language: Native Kashmiri language, Hindi and Urdu Cuisine: Mostly meat, wheat, rice, and maize. - In Jammu and Kashmir, rice, meat, and wheat are big parts of their cuisines because wheat and rice are a huge part of their agriculture. Agriculture of Jammun and Kashmir - The Jammu plain has a high concentration of wheat, rice, maize, pulses, fodder and oilseeds. - The Valley of Kashmir is well known for its paddy, maize, orchards (apples, al mond, walnut, peach, cherry, etc.) and saffron cultivation. - Depending on the rainfall, the hectarages that produce rice and maize vary substantially. - Wheat is used as a staple in Jammu - Maize is used as a staple in Kashmir - Jammu and Kashmir are primarily an agrarian state. - Large orchards in the Vale of Kashmir produce apples, pears, peaches, walnuts, almonds, and cherries, which are among the state’s major exports. Popular Dishes from Jammu and Kashmir - Rogan Josh - An aromatic curried meat dish of Kashmiri origin. It is made with red meats like lamb or goats. It is colored or flavored by alkanet flower or Kashmiri chilies. - Butter Tea - Butter tea is also known as Po Cha. It mainly uses tea leaves, yak butter, and salt. - Pilaf - This is a wheat dish. It is usually coooked in stock or broth and spices are added. Some other things that are added are vegetables or meat. - Dum Aloo - This is a potato based dish. -

Onam Onam-Harvest Festival of Kerala • Onam Is the Biggest and the Most Important Festival of the State of Kerala, India

Onam Onam-Harvest Festival of Kerala • Onam is the biggest and the most important festival of the state of Kerala, India. • It is a harvest festival and is celebrated with joy and enthusiasm by Malayalis (Malayalam speaking people) all over the world. It celebrates rice harvest. • Onam is celebrated in the beginning of the month of Chingam, the first month of Malayalam Calendar (Kollavarsham), which in Gregorian Calendar corresponds to August-September. Chingam 1 is the New Year day for Malayali Hindus. • It celebrates the Vamana (fifth avatar of god Vishnu) avatar of Vishnu (principal deity of Hinduism). • It is celebrated to welcome King Mahabali, whose spirit is said to visit Kerala at the time of Onam. • The festival goes on for ten days. • Onam celebrations include Vallamkali (boat race), Pulikali (tiger dance), Pookkalam (floral carpet), Onathappan (worship), Vadamvali (Tug of War), Thumbi Thullal (women's dance), Kummattikali (mask dance), Onathallu (martial arts), Onavillu (music), Kazhchakkula (plantain offerings), Onapottan (costumes), Atthachamayam (folk songs and dance), and other celebrations. Vallamkali Pulikali Pookkalam Onathappan Vadamvali Thumbi Thullal Onathallu Kummattikali Onavillu Atthachamayam Onapottan Kazhchakkula Significance • King Mahabali was also known as Maveli and Onathappan. Mahabali was the great great grandson of a Brahmin sage named Kashyapa , the great grandson of demonic dictator Hiranyakashipu, and the grandson of Vishnu devotee Prahlada. Prahlada, was born to a demonic Asura father who hated Vishnu. Despite this, Prahlada rebelled against his father's ill-treatment of people and worshipped Vishnu. • Hiranyakashipu tried to kill his son Prahlada, but was slained by Vishnu in his Narasimha avatar, Prahlada was saved. -

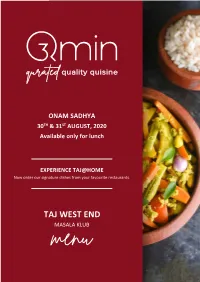

Qmin-Taj-West-End-Onam-Sadhya

ONAM SADHYA 30TH & 31ST AUGUST, 2020 Available only for lunch EXPERIENCE TAJ@HOME Now order our signature dishes from your favourite restaurants. TAJ WEST END MASALA KLUB DELIVERY GUIDELINES WITHIN 8 KM CONTACTLESS ONLINE PAYMENT RADIUS DELIVERY VIA UPI SUSTAINABLE SAFETY & PACKAGING HYGIENE ASSURED MASALA KLUB Vegetarian Sadhya Sharkara uperi Jaggery flavored sweet banana chips Nendra uperi Kerala banana chips Papadam Crispy flat bread Poovan pazham Small ripened banana Pacha manga achar Fresh instant mango pickle Inji pulli Sweet ginger chutney Naranga curry Fresh lemon pickle Pineapple pachadi Mélange of pineapple, yoghurt and coconut Kakirika kichadi Cucumber with coconut and yoghurt with mustard tempering Payar mezhukupara� S�r-fried long beans in coconut oil with curry leaf and onion Cabbage thoran S�r-fried cabbage and coconut tempered with mustard and curry leaf Avial Braised vegetables with coconut and yoghurt gravy Kalan Yam simmered in sour coconut gravy Olan White pumpkin and long beans stew Kootu curry Black gram and raw banana simmered in fried coconut gravy Ulli theeyal Sweet and sour baby onion Steamed kerala rice Steamed unpolished red rice Parippu curry Plain len�l curry Neyy Ghee Sambhar Kerala style sambar flavored with coconut Moru kachiyethu Tempered yoghurt gravy Rasam Spicy, sweet and sour extract from tomato, coriander and len�l water Ada pradhaman Delicious payasam made with rice flakes, jaggery and coconut milk Paal payasam Rice pudding made with short grain rice and milk THANK YOU FOR FURTHER ORDERS, PLEASE CALL: 1800 266 7646 Timings: 12:00 PM to 3:00 PM. -

View in 1986: "The Saccharine Sweet, Icky Drink? Yes, Well

Yashwantrao Chavan Maharashtra Open University V101:B. Sc. (Hospitality and Tourism Studies) V102: B.Sc. (Hospitality Studies & Catering Ser- vices) HTS 202: Food and Beverage Service Foundation - II YASHWANTRAO CHAVAN MAHARASHTRA OPEN UNIVERSITY (43 &Øا "••≤°• 3•≤©£• & §°© )) V101: B. Sc. Hospitality and Tourism Studies (2016 Pattern) V102: B. Sc. Hospitality Studies and Catering Services (2016 Pattern) Developed by Dr Rajendra Vadnere, Director, School of Continuing Education, YCMOU UNIT 1 Non Alcoholic Beverages & Mocktails…………...9 UNIT 2 Coffee Shop & Breakfast Service ………………69 UNIT 3 Food and Beverage Services in Restaurants…..140 UNIT 4 Room Service/ In Room Dinning........................210 HTS202: Food & Beverage Service Foundation -II (Theory: 4 Credits; Total Hours =60, Practical: 2 Credits, Total Hours =60) Unit – 1 Non Alcoholic Beverages & Mocktails: Introduction, Types (Tea, Coffee, Juices, Aerated Beverages, Shakes) Descriptions with detailed inputs, their origin, varieties, popular brands, presentation and service tools and techniques. Mocktails – Introduction, Types, Brief Descriptions, Preparation and Service Techniques Unit – 2 Coffee Shop & Breakfast Service: Introduction, Coffee Shop, Layout, Structure, Breakfast: Concept, Types & classification, Breakfast services in Hotels, Preparation for Breakfast Services, Mise- en-place and Mise-en-scene, arrangement and setting up of tables/ trays, Functions performed while on Breakfast service, Method and procedure of taking a guest order, emerging trends in Breakfast -

Onasamsakal! Happy Onam Varnakairali Is Back After Three Years of Dormancy

PERSATUAN MALAYALEE SELANGOR & WILAYAH PERSEKUTUAN SELANGOR & FEDERAL TERRITORY MALAYALEE ASSOCIATION Issue 1, 2015-2016 | FOR MEMBERS ONLY PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Greetings to all members. Namaskaram! Onasamsakal! Happy Onam Varnakairali is back after three years of dormancy. To call it dormancy is not entirely correct. It was a forced dormancy to all members! with many members of the Exco Committee expressing various views on the need to have a Newsletter in this era of technology. Websites and social media such as Facebook etc seem to be the order of the day. Postal rates to join SFTMA. In this issue we are enclosing a have increased followed with unreliable service. membership form to be passed to your friends and family. However, this changed with the return of old guards into Over the next few months, we have lined up many the Committee in 2015. The newly elected Exco activities starting off with the Onam Sadhya (August 30) Committee is an amalgam of both the old and new. Thus, and the Onam Cultural Nite 2015 (September 19) to leaving a perfect balance to serve members of all age mention a few. Our Ladies Wing has been very active over groups. Yes! The new Committee is committed to serve its the last one year but was unable to reach out to members members and this issue of the Varnakairali is the first canon due to website and emails, not being patronized by most to announce its arrival. Therefore, I urge all members of senior members. Hence, the need to revive the newsletter. SFTMA to update your membership record by furnishing us I would like to take this opportunity to thank Ms. -

Research Paper Impact Factor: 3.996 Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal IJMSRR E- ISSN

Research Paper IJMSRR Impact Factor: 3.996 E- ISSN - 2349-6746 Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal ISSN -2349-6738 RESEARCH ON INDIAN FOOD HABITS AND HEALTH Prof. Sandeep R Shelar Asst. Professor, Maharashtra State Institute of Hotel Management, Pune. Abstract The main purpose of this paper is to find food preferences amongst different age groups, gender, region with respect to fast food, brands, home-made and hotels. As the health of many people is deteriorating by consuming fast food on streets and packed food. Many dieticians are expressing concern over such consumption leading to chronic diseases. We are aware of this fact that young couples are not finding time to eat home-made food.Old people are aware of warning of dieticians not to use fast food for health reasons. Keywords- Food habits, Fast food, Home food, Hotel, Region, Age groups, Preferences affordable. Introduction The human diet plays an important role for good health and long life. India is a country with diverse culture, habits, customs, religious dogma, communal and linguistic differences and being a country dominant to house more critical diseases like diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, TB, cancer, AIDS, leprosy and many ailments. Yoga, meditation, exercise, sound sleep and relaxation are other components responsible to enjoy good health and long life. Good diet is a blend of carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, minerals, fats and water. But the human tongue does not accept the corrects proportion of food elements mentioned here and sometimes fats increases to harm our body. We say three enemies of mankind are SALT, SUGAR, AND MAIDA three dangerous whites which are found in large proportion in FAST FOOD to harm our body function.We have invited diseases due to lack of good diet, lack of exercise, and less sleep. -

A Sweet Melange Of

CULTURE CURRY CUisiNE www.trujetter.com A sweet melange of STAPLES Payasam, in several variants, is a creamy rice pudding with milk, jaggery and lentils, and a delicacy that no meal in South india is complete without. Words: Mini RibeiRo he word payasam, Payasam or Pradhaman Traditionally for making ada is derived from forms an integral part of the or rice flakes, a dough is made Peeyusham, Kerala feast (sadya), where it of rice flour and coconut oil, or meaning nectar or is served and relished from the soaked rice is ground to a paste. ambrosia. Many banana leaf directly, instead of This is then flattened on a banana alsoT believe it emanates from the cups. According to Chef Ramesh leaf and steamed. It is then cooled Sanskrit word, ‘payas’ or milk. Kukreti, Head Chef, Courtyard by and cut into small pieces. The ada Payasam has several variants Marriott, Kochi, “Payasam is a is then cooked with coconut milk across the southern states, albeit popular dessert and an integral and jaggery in an uruli or copper with minor variations and is part of the Sadhya. Milk, nuts, vessel, till thick. generally served on festivals and fruits and aromatic spices like Palada payasam is another weddings, as part of the meal. saffron, kewra, cardamom and common dessert here, made with Payasam is usually eaten after the tulsi are combined to prepare milk and rice flakes where the milk rasam rice course, while rice with different varieties. Payasam is is condensed slowly through fire buttermilk forms the last item of also distributed as Prasadam in and evaporation. -

Studio Menu.Cdr

Spice odyssey @ Aed 495 Pani puri, sweet potato, preserved lemon, roasted cumin Shiso khakra, yogurt cremeux, raw mango chutney, garden herbs Chaat mille-feuille, courgette blossom, pumpkin mash Lamb & turnip tartlet, nasturtium leaf, marigold Pickled chili, tangerine gem, buttermilk curry ice cream Ghee roast crab, burnt cinnamon, potato crisp Tomato broth, chicken fat dumpling, crisp coriander Kebab scarpetta, sour dough bun Tomato rasam, prawn & potato salad, chili jaggery chutney Duck leg confit, fermented chili, peanut butter curry 'Sadhya' pineapple, coconut & pink peppercorn payasam, mango pickle, poppadum Filter coffee cornetto, chocolate ganache miso caramel ice cream Cocoa hive, queen bee sidr honey, kan-junga tea the courses on the menu may change based on the availability of ingredients please advise the server should you be allergic to any ingredient / have dietary restrictions all prices are in aed, inclusive of 7% municipality fee, 5% vat & 10% service charge Spice odyssey @ Aed 495 Vegetarian Pani puri, sweet potato, preserved lemon, roasted cumin Shiso khakra, yogurt cremeux, raw mango chutney, garden herbs Chaat mille-feuille, courgette blossom, pumpkin mash Turnip tartlet, nasturtium leaf, marigold Pickled chili, tangerine gem, buttermilk curry ice cream Ghee roast jackfruit, burnt cinnamon, curry leaf crisp Tomato and lentil broth, fermented lentil grit, coriander crisp Kebab scarpetta, sour dough bun Tomato rasam, asparagus & potato salad, chili jaggery chutney Smoked eggplant, fermented chili, peanut butter curry 'Sadhya' pineapple, coconut & pink peppercorn payasam, mango pickle, poppadum Filter coffee coral, chocolate parfait, miso caramel ice cream Cocoa butter hive, queen bee sidr honey, kan-junga tea the courses on the menu may change based on the availability of ingredients please advise the server should you be allergic to any ingredient / have dietary restrictions all prices are in aed, inclusive of 7% municipality fee, 5% vat & 10% service charge. -

Diasporic Tastescapes : Intersections of Food and Identity In

Diasporic Tastescapes: Intersections of Food and Identity in Asian American Literature Os sabores da diáspora: comida e identidade na literatura asiático-americana Paula Torreiro Pazo Doctoral Thesis/Tese de doutoramento UDC 2014 Directora e titora da tese: Dra. Begoña Simal González Departamento de Filoloxía Inglesa A meus pais, por crer en min. Por acompañarme e darme forzas neste longo camiño. O meu agradecemento á miña titora, Begoña Simal González, pola súa inspiración e valiosos consellos. Abstract Diasporic Tastescapes: Intersections of Food and Identity in Asian American Literature This dissertation seeks to explore the culinary metaphors present in a selection of Asian American narratives written by authors such as Jhumpa Lahiri, May-lee Chai, Shoba Narayan, Leslie Li, Bich Minh Nguyen, Linda Furiya, Mei Ng, Lois-Ann Yamanaka, Patricia Chao, Shirley Geok-lin Lim, Anita Desai, Sara Chin and Andrew X. Pham. It is my contention that the intricate web of culinary motifs featured in these texts offers a fertile ground for the study of the real and imaginary [hi]stories of the Asian American community, an ethnic minority that has been persistently racialized through its eating habits. Thus, I will examine those literary contexts in which the presence of food images becomes especially meaningful as an indicator of the nostalgia of the immigrant, the sense of community of the diasporic family, the clash between generations, or the shocks of arrival and return. My approach to the culinary component will combine previous theorizations on the subject, such as Sau-ling Cynthia Wong’s or Anita Mannur’s, at the same time that I provide new points of departure from which to look into the trope of food against the backdrop of globalization and transnationalism. -

Exploring and Re-Envisioning the Significance of Agrarian Consciousness in Theology with Specific Reference to Kerala

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-8-2020 Exploring and Re-envisioning the Significance of Agrarian Consciousness in Theology with Specific Reference to Kerala Jinto George Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Other Religion Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation George, J. (2020). Exploring and Re-envisioning the Significance of Agrarian Consciousness in Theology with Specific Reference to Kerala (Master's thesis, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1900 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. EXPLORING AND RE-ENVISIONING THE SIGNIFICANCE OF AGRARIAN CONSCIOUSNESS IN THEOLOGY WITH SPECIFIC REFERENCE TO KERALA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of McAnulty Graduate College of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the degree of Master of Arts By Jinto George May 2020 Copyright by Jinto George 2020 EXPLORING AND RE-ENVISIONING THE SIGNIFICANCE OF AGRARIAN CONSCIOUSNESS IN THEOLOGY WITH SPECIFIC REFERENCE TO KERALA By Jinto George Approved April 15th, 2020 _______________________________ ________________________________ Dr. Gerald Boodoo, Ph.D. -

Kerala Cuisine

KERALA CUISINE The cuisine of Kerala is linked in all its richness to the history, geography, demography and culture of the land. Because many of Kerala's Hindus are vegetarian by religion (e.g., brahmins or namboodiris,Nairs etc.), and because Kerala has large minorities of Muslims and Christians that are predominantly non-vegetarian, Kerala cuisine has a multitude of both vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes. Like other South-Indian cuisines, Kerala cuisine (called pachakam in Malayalam) is predominantly spicy. Coconuts grow in abundance in Kerala, and consequently, grated coconut and coconut milk are widely used in dishes and curries. Kerala's long coastline and strong fishing industry has contributed to many fish-based delicacies, particularly among the Christian community. HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL INFLUENCES Pre-independence Kerala was split into the princely states of Travancore and Kochi in the south, and the Malabar district in the north; the erstwhile split is reflected in the cuisines of each area. Malabar has an array of non- vegetarian dishes such as pathiri (a sort of rice-based pancake, usually paired with a meat curry), porotta (a layered flatbread), and the kerala variant of the popular biriyani. In contrast, traditional Travancore cuisine consists of a variety of vegetarian dishes using many vegetables and fruits that are not commonly used in curries elsewhere in india including plantains, bitter gourd ('paavaykka'). Amorphophallus ('chena'), Colocasia ('chembu'), Ash gourd ('kumbalanga'), etc. Garlic is predominantly used in south-kerala dishes as well. In addition to historical diversity, the cultural influences, particularly the large percentages of Muslims and Syrian Christians (also see Syrian Christian Cuisine of Kerala) have also contributed unique dishes and styles to Kerala cuisine. -

Feasts, Flavours & Fusion of India

FEASTS, FLAVOURS & FUSION OF INDIA CURIOUS CULTURE OF CULINARY INDIA REVIEW N ultimate guide to the best of the rest exotic A culinary Indian Cuisines. This tasteful saga of spices, ingredients, culture, tradition, evolution & now customisation is all served on a single platter in the ensuing pages. Where dishes vary not only from region to region but suburb to suburb, the series and scope of local delicacies is endless: from Moghul biryanis, Punjabi dal makhani and Kashmiri goshtaba being just a few. The research team behind this book walked through the nook & cranny of the length and breadth of India, talking to chefs, tasting the delightful dishes and visiting localities, offering an honest, insider view of the country's culinary delights and history. The creatives & pictures showcases the vivacity and shades related with the East, West, North & South and then reflected in the colourful dishes whose recipes accompany them. An apt book for any lover of Indian food. DIVERSED TASTES, ONE INDIA North of India: Origin & Belief North Indians and their delicacies are undividable. Northern Indians are known as serious food lovers and cooking for this NDIA is known clan is no less than for its diversity a ritual when found in its compared to other culture, geography parts of the country. I and climate. Food too is part of the diverse delight as each state exhibits a different way of life, language and cuisine. Traversing through the Indian food map, whether you are travelling up north in Kashmir or spending a few days down south to Kerala, you will observe striking dissimilarities in the kind of food people relish.