Rethinking the EU's Mediterranean Policies Post-1/11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Interview with Jacques BARROT,Former Vice-President Of

INTERVIEW European Interview n°56 14th June 2011 “Immigrants who fit in well can add value to European society, stimulate it and facilitate its opening onto the world” European Interview with Jacques BARROT, former Vice-President of the European Commission for Trans- port, then for Justice, Freedom and Security, member of the Constitutional Council of the French Republic, former minister result there has been a real confidence crisis between 1. In the present unstable geopolitical context the Member States. It is now urgent, as requested in North Africa, around 20,000 migrants[1], by the European Commissioner for Internal Affairs, mainly from Tunisia, have entered the European Cecilia Malmström, to give the European Commission Union illegally. This movement has fed European the responsibility of ensuring that these rules are im- concern, contrasting with support for the demo- plemented and if necessary for it to authorise exemp- cratic revolutions ongoing in these countries. tions that will enable the re-establishment of inter- How do you see the present tension? How can nal border controls in the event of serious, specific Europe show that it supports the countries in circumstances. However guidelines should be enough Northern Africa? without having to question rules that are specific to the Schengen area and which are a precious asset for Excessive fear has been maintained by simplistic po- all Europeans. pulist response without there being any estimation of what the real dangers are. It is true that the situation 3. On 3rd May last, the European Commission in Libya could be the cause for real concern because of published a Communication on migration the great number of sub-Saharan Africans living there. -

Portfolio Responsibilities of the Barroso Commission

IP/04/1030 Brussels, 12 August 2004 Portfolio Responsibilities of the Barroso Commission Responsibilities Departments1 José Manuel BARROSO President Responsible for: - Political guidance of the Commission - Secretariat General - Organisation of the Commission in - Legal Service order to ensure that it acts - Spokesperson consistently, efficiently and on the - Group of Policy Advisers (GOPA) basis of collegiality - Allocation of responsibilities Chair of Group of Commissioners on Lisbon Strategy Chair of Group of Commissioners for External Relations Margot WALLSTRÖM Vice President Commissioner for Institutional Relations and Communication Strategy Press and Communication DG including Responsible for: Representations in the Member States - Relations with the European Parliament - Relations with the Council and representation of the Commission, under the authority of the President, in the General Affairs Council - Contacts with National Parliaments - Relations with the Committee of the Regions, the Economic and Social Committee, and the Ombudsman - Replacing the President when absent - Coordination of press and communication strategy Chair of Group of Commissioners for Communications and Programming 1 This list of department responsibilities is indicative and may be subject to adjustments at a later stage Günter VERHEUGEN Vice President Commissioner for Enterprise and Industry Responsible for: - DG Enterprise and Industry - Enterprise and industry (renamed), adding: - Coordination of Commission’s role in - Space (from DG RTD) the Competitiveness -

Annual Report 2007/2008

Annual Report 2007/2008 The Voice of European Railways COMMUNITY OF EUROPEAN RAILWAY AND INFRASTRUCTURE COMPANIES COMMUNAUTÉ EUROPÉENNE DU RAIL ET DES COMPAGNIES D’INFRASTRUCTURE GEMEINSCHAFT DER EUROPÄISCHEN BAHNEN UND INFRASTRUKTURGESELLSCHAFTEN Table of Contents Foreword . .2 Guest .contribution Vice-President .of .the .european .commission .responsible .for .transport . Jacques .barrot . .4 in .Focus Promoting .rail .freight .corridors . .6 Transport policy of the European Commission . .6 Communication on a rail freight network . .8 CER concept for a Primary European Rail Freight Network . .9 Challenges for the future . .11 .external .costs .of .transport .and .the .revision .of .the .eurovignette .directive . .13 An unbalanced situation in the European freight market . .13 The Eurovignette Directive – a tool for a solution? . .14 Signs of progress – latest EU development . .15 Follow the Swiss! . .16 Interview with Werner Rothengatter . ..17 other .rail .Policy .deVeloPments the .risks .of .mega-trucks .on .europe’s .roads . .19 Developments .regarding .rail .passenger .transport . .20 Financing .rail .transport . .23 Progress .on .social .dialogue . .25 customs .and .security . .27 Further .progress .on .interoperability .legislation . .29 chronology: .Political .events .2007/2008 . .30 cer .eVents .2007/2008 conference .“Fighting .climate .change .– .the .potential .of .rail .transport” . .34 First .european .railway .award . .35 chronology .of .cer .activities . .36 about .cer member .railway .and .infrastructure .companies . .42 . cer .governance . .46 Annual Annual Report 2007/2008 cer .team . .52 cer .publications .2007/2008 . .54 railway .statistics .2007 . .55 list .oF .abbreViations . .58 20 .years .oF .cer: .time .line .1988 .- .2008 . .61 1 Foreword 2008 is a significant year for CER and a crucial year for rail transport in Europe. -

REY Commission (1967-1970)

COMPOSITION OF THE COMMISSION 1958-2004 HALLSTEIN Commission (1958-1967) REY Commission (1967-1970) MALFATTI – MANSHOLT Commission (1970-1973) ORTOLI Commission (1973-1977) JENKINS Commission (1977-1981) THORN Commission (1981-1985) DELORS Commission (1985) DELORS Commission (1986-1988) DELORS Commission (1989-1995) SANTER Commission (1995-1999) PRODI Commission (1999-2004) HALLSTEIN COMMISSION 1 January 1958 – 30 June 1967 TITLE RESPONSIBLITIES REPLACEMENT (Date appointed) Walter HALLSTEIN President Administration Sicco L. MANSHOLT Vice-President Agriculture Robert MARJOLIN Vice-President Economics and Finance Piero MALVESTITI Vice-President Internal Market Guiseppe CARON (resigned September 1959) (24 November 1959) (resigned 15 May 1963) Guido COLONNA di PALIANO (30 July 1964) Robert LEMAIGNEN Member Overseas Development Henri ROCHEREAU (resigned January 1962) (10 January 1962) Jean REY Member External Relations Hans von der GROEBEN Member Competition Guiseppe PETRILLI Member Social Affairs Lionello LEVI-SANDRI (resigned September 1960) (8 February 1961) named Vice-president (30 July 1064) Michel RASQUIN (died 27 April 1958) Member Transport Lambert SCHAUS (18 June 1958) REY COMMISSION 2 July 1967 – 1 July 1970 TITLE RESPONSIBLITIES REPLACEMENT (Date appointed) Jean REY President Secretariat General Legal Service Spokesman’s Service Sicco L. MANSHOLT Vice-president Agriculture Lionelle LEVI SANDRI Vice-president Social Affairs Personnel/Administration Fritz HELLWIG Vice-president Research and Technology Distribution of Information Joint -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, C(2010) 3652 Final REPORT

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, C(2010) 3652 final REPORT FINANCIAL REPORT ECSC in Liquidation at 31 December 2009 EN EN EN FINANCIAL REPORT ECSC in Liquidation at 31 December 2009 Contents page Activity report 5 Expiry of the ECSC Treaty and the management mandate given to the European Commission 6 Winding-up of the ECSC financial operations in progress on expiry of the ECSC Treaty 7 Management of assets 12 Financing of coal and steel research 13 Financial statements of the ECSC in liquidation 14 Independent Auditor’s report on the financial statements 15 Balance sheet at 31 December 2009 17 Income statement for the year ended 31 December 2009 18 Statement of changes in equity for the year ended 31 December 2009 19 Cash flow statement for the year ended 31 December 2009 20 Notes to the financial statements at 31 December 2009 21 A. General information 21 B. Summary of significant accounting policies 22 C. Financial Risk Management 27 D. Explanatory notes to the balance sheet 36 E. Explanatory notes to the income statement 47 F. Explanatory notes to the cash flow statement 52 G. Off balance sheet 53 H. Related party disclosures 53 I. Events after the balance sheet date 53 EN 2 EN ECSC liquidation The European Coal and Steel Community was established under the Treaty signed in Paris on 18 April 1951. The Treaty entered into force in 1952 for a period of fifty years and expired on 23 July 2002. Protocol (n°37) on the financial consequences of the expiry of the ECSC Treaty and on the creation and management of the Research Fund for Coal and Steel is annexed to the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union. -

Top Margin 1

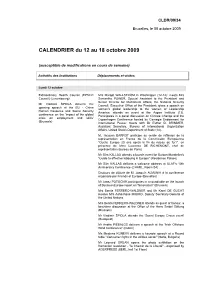

CLDR/09/34 Bruxelles, le 08 octobre 2009 CALENDRIER du 12 au 18 octobre 2009 (susceptible de modifications en cours de semaine) Activités des Institutions Déplacements et visites Lundi 12 octobre Extraordinary Health Council (EPSCO Mrs Margot WALLSTRÖM in Washington (12-14): meets Mrs Council) (Luxembourg) Samantha POWER, Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Multilateral Affairs, the National Security Mr Vladimír ŠPIDLA delivers the Council, Executive Office of the President; gives a speech on opening speech at the EU - China women's global leadership to the women of Leadership Human Resource and Social Security America; attends an event at the Aspen Institute (13). conference on the 'impact of the global Participates in a panel discussion on Climate Change and the crisis on employment and skills' Copenhagen Conference hosted by Carnegie Endowment for (Brussels) International Peace; meets with Dr Esther D. BRIMMER, Assistant Secretary, Bureau of International Organization Affairs, United States Department of State (14). M. Jacques BARROT participe au cercle de réflexion de la représentation en France de la Commission Européenne "Quelle Europe 20 ans après la fin du rideau de fer?", en présence de Mme Laurence DE RICHEMONT, chef de représentation (bureau de Paris) Mr Siim KALLAS attends a launch event for Burson-Marsteller's "Guide to effective lobbying in Europe" (Residence Palace) Mr Siim KALLAS delivers a welcome address at OLAF's 10th Anniversary Conference (CHARL, Room S4) Discours de clôture de M. Joaquín ALMUNIA -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Gijón, 19 November 2007 Ref: CRPMCOM070052 PORTS AND MARITIME TRANSPORT - SEMINAR IN GIJÓN - In order to discuss the usefulness of an EU ports policy, the role of maritime transport in neighbourhood policy, the maritime transport priorities of the EU, as well as to reduce road congestion and to contribute to sustainable development, the CPMR organised a seminar on the 19 November 2007 in Gijón (Asturias-ES) at the invitation of Mr Álvarez Areces, President of the Principality of Asturias , with the backing of the City and Port Authority of Gijón. Jacques Barrot, European Commissioner for Transport, contributed to the discussions by demonstrating how the EU was very open-minded with regards to maritime transport. “The CPMR must play its part more than ever, as globalisation is increasing transport and in particular maritime transport, which is one of the most compatible with the environment,” declared Jacques Barrot in his speech on the issue of ports, motorways of the sea and maritime safety. “For motorways of the sea to be more interesting, we need to simplify the bureaucracy for the delivery of goods and an integrated maritime space will help us meet this challenge. Today, maritime transport is not competitive as customs controls apply even to deliveries within the EU,” concluded the French Commissioner. This attitude was also shared by other speakers representing the EU: Mr Luis Grandes Pascual , Member of the European Parliament Committee on Transport, Mr Jean Trestour , Head of Unit at DG TREN, European Commission, and Mrs Natércia Cabral, Chairperson, Institute for Ports and Maritime Transport, Portugal who spoke on behalf of the EU Presidency . -

Politics: the Right Or the Wrong Sort of Medicine for the EU?

Policy paper N°19 Politics: The Right or the Wrong Sort of Medicine for the EU? Two papers by Simon Hix and Stefano Bartolini Notre Europe Notre Europe is an independent research and policy unit whose objective is the study of Europe – its history and civilisations, integration process and future prospects. The association was founded by Jacques Delors in the autumn of 1996 and presided by Tommaso Padoa- Schioppa since November 2005. It has a small team of in-house researchers from various countries. Notre Europe participates in public debate in two ways. First, publishing internal research papers and second, collaborating with outside researchers and academics to contribute to the debate on European issues. These documents are made available to a limited number of decision-makers, politicians, socio-economists, academics and diplomats in the various EU Member States, but are systematically put on our website. The association also organises meetings, conferences and seminars in association with other institutions or partners. Proceedings are written in order to disseminate the main arguments raised during the event. Foreword With the two papers published in this issue of the series “Policy Papers”, Notre Europe enters one of the critical debates characterising the present phase of the European construction. The debate revolves around the word ‘politicisation’, just as others revolve around words like ‘democracy’, ‘identity’, bureaucracy’, ‘demos’, ‘social’. The fact that the key words of the political vocabulary are gradually poured into the EU mould is in itself significant. In narrow terms, the issue at stake is whether the European institutions should become ‘politicised’ in the sense in which national institutions are, i.e. -

Strengthening Transport Cooperation with Neighbouring Countries

IP/07/119 Brussels, 31st January 2007 Strengthening transport cooperation with neighbouring countries The European Commission adopted today a Communication on "Guidelines for transport in Europe and neighbouring regions". It outlines an ambitious policy in view of creating an effective transport market involving the EU and its neighbours and of spreading the principles of internal market. The Communication identifies the five most important transport axes for international trade between the Union and the neighbouring countries and beyond. It also puts forward a package of measures to shorten journey times along these axes including improvement of infrastructure, streamlining of customs procedures and reducing administrative obstacles. In order to make this policy a reality and boost cooperation between the European Union and the neighbouring regions, the Commission will launch exploratory talks with all the countries concerned. "By putting forward an ambitious yet feasible set of measures for the transport sector, the Guidelines contribute to better integrating the economies and transport systems the EU and its neighbours but also to fostering regional cooperation between the neighbouring countries themselves", said Vice- President Jacques Barrot, Commissioner for Transport. "I would particularly like to pay homage to Loyola de Palacio, departed from us too soon, whose dedication to the transeuropean transport network has today been concretised" declared Vice- President Jacques Barrot. The extension of networks to neighbouring countries is one of the objectives set out in the recent Communication on the ‘Strengthening of the European Neighbourhood Policy’1. “Improving our transport links with our neighbours will not only mean closer relations with them but it will also generate more trade and tourism. -

25 Years of CER and EU Transport Policy

25 Years of CER and EU transport policy On the right track for a single European railway area? June 2013 The Voice of European Railways Design and production: Tostaky - www.tostaky.be Photos kindly provided by CER members and http://ec.europa.eu Printed in Belgium in June 2013 Publisher: Community of European Railway and Infrastructure Companies (CER) Avenue des Arts 53, 1000 Brussels - Belgium - www.cer.be Disclaimer CER, nor any person acting on its behalf, may be held responsible for the use to which information contained in this publication may be put, nor for any errors which may appear despite careful preparation and checking. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. Foreword Back in 1988, 14 railway companies felt the need to establish a stronger link with the European institutions following increasingly significant political developments in transport. As a result, CER was founded as an independent group of the International Union of Railways (UIC) with its own offices in Brussels. Soon after this, in 1991, the European Commission began the first of its initiatives to regulate the railway sector by adopting the foundation for rail market opening - Directive 91/440/EEC. A number of other important rail legislative proposals followed: the first railway package was published in 2001, the second in 2004, the third in 2007, and the fourth one in January 2013. CER, representing the vast majority of EU rail business, has always been at the forefront in helping shape rail regulation. CER became an independent body in 1996, and the membership grew quickly to its current level of 82 railway undertakings, infrastructure companies and vehicle leasing companies. -

Robert Schuman Medal

ROBERT SCHUMAN MEDAL AWARDED TO ON AWARDED TO ON The EPP Group in the European Parliament Ursula SCHLEICHER 15.05.1998 Guido de MARCO 04.07.2007 Founded as the Christian-Democratic Group on 23 June 1953 Anibal CAVACO SILVA 08.07.1998 Marianne THYSSEN 30.06.2009 as a fraction in the Common Assembly of the European Coal Poul SCHLÜTER 13.04.1999 Jaime MAYOR OREJA 30.06.2009 and Steel Comm unity, the Group changed its name to the Radio B2 92, Belgrade 14.12.1999 Hartmut NASSAUER 30.06.2009 'Group of the European People’s Party' (Christian-Democratic Martin LEE 18.01.2000 João de Deus PINHEIRO 30.06.2009 Libet WERHAHN-ADENAUER 01.12.2000 Ioannis VARVITSIOTIS 30.06.2009 Group) in July 1979, just after the first direct elections to Elena BONNER-SAKHAROV 03.04.2001 José Manuel BARROSO 30.06.2009 the European Parliament, and to 'Group of the European Karl von WOGAU 14.11.2001 Jacques BARROT 30.06.2009 People’s Party (Christian Democrats) and European Democrats' Nicole FONTAINE 15.01.2002 László TŐKÉS 16.12.2009 (EPP-ED) in July 1999. After the European elections in 2009, Ingo FRIEDRICH 26.01.2002 Alberto João JARDIM 13.10.2010 the Group went back to its roots as the 'Group of the European Wladylaw BARTOSZEWSKI 26.02.2002 Pietro ADONNINO 04.05.2011 José Maria AZNAR 01.07.2002 Peter HINTZE 19.01.2012 People's Party (Christian Democrats)'. It has always played a Hans van den BROEK 02.11.2002 Íñigo MÉNDEZ de VIGO 08.03.2012 leading role in the construction of Europe. -

CALENDRIER Du 26 Mai Au 1Er Juin 2008

MEMO/08/331 Bruxelles, le 23 mai 2008 CALENDRIER du 26 mai au 1er juin 2008 (susceptible de modifications en cours de semaine) Activités des Institutions Déplacements et visites Lundi 26 mai Conseil Affaires générales et Relations Mr José Manuel Durão BARROSO receives Mr Philippe extérieures (Défense + Développement) MAYSTADT, President of the European Investment Bank (EIB) (Bruxelles) (26-27) Mr José Manuel Durão BARROSO receives Mr Franco FRATTINI, Réunion informelle des Ministres Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs "Agriculture" (Maribor & Brdo, Slovénie) (26-27) Mr José Manuel Durão BARROSO participates at the conference on European Policy Centre (Concert Noble) Mr José Manuel Durão BARROSO attends the Energy Globe Award (EP) Mrs Margot WALLSTRÖM receives Mr Ranil WICKREMESINGHE, leader of the Opposition Sri Lanka Mr Janez POTOČNIK at the EU-Russia Permanent Partnership Council meeting Mr Siim KALLAS delivers a speech :"An Introduction to Building on Research (Brdo) Europe" at the Colloquium on "Corporations and Cities" (Flagey Building) Mr Olli REHN at the Joint Parliamentary Meeting on the Western Balkans MM. Jacques BARROT et Olli REHN avec M. Nikola SPIRIC, le (Brussels) Président du Conseil des Ministres de la Bosnie Herzegovine ouvrent le dialogue sur le déplacement sans visa Mr Peter MANDELSON participates in the EU-Gulf Cooperation Council M. Jacques BARROT reçoit M. Francis JACOB, Président de Missing Children Europe et M. Francis HERBERT, Secrétaire Général de Missing Children Europe Mr Joaquín ALMUNIA at the signature of a Memorandum of Understanding with Philippe MAYSTADT, President of the European Investment Bank (EIB) to improve coordination of EU external lending policies and action Visite de Mme Danuta HÜBNER en France (Orléans -Bourges): rencontre avec le Préfet Jean-Michel BERARD); intervention à la "Présentation de la mise en œuvre de la stratégie de Lisbonne dans les outils de programmation" à l'Hôtel de la Préfecture; point de presse; entretien avec M.