The Senkawa Josui: the Changing Uses of a Constructed Waterway in Early Modern and Modern Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Certified Facilities (Cooking)

List of certified facilities (Cooking) Prefectures Name of Facility Category Municipalities name Location name Kasumigaseki restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Tokyo-club Building,3-2-6,Kasumigaseki,Chiyoda-ku Second floor,Sakura terrace,Iidabashi Grand Bloom,2-10- ALOHA TABLE iidabashi restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 2,Fujimi,Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku banquet kitchen The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 24th floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Peter The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Boutique & Café First basement, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku Second floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku Hei Fung Terrace The Peninsula Tokyo hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First floor, The Peninsula Tokyo,1-8-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku The Lobby 1-1-1,Uchisaiwai-cho,Chiyoda-ku TORAYA Imperial Hotel Store restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (Imperial Hotel of Tokyo,Main Building,Basement floor) mihashi First basement, First Avenu Tokyo Station,1-9-1 marunouchi, restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku (First Avenu Tokyo Station Store) Chiyoda-ku PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Hot hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku Kitchen,Cold Kitchen) PALACE HOTEL TOKYO(Preparation) hotel Tokyo Chiyoda-ku 1-1-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku LE PORC DE VERSAILLES restaurant Tokyo Chiyoda-ku First~3rd floor, Florence Kudan, 1-2-7, Kudankita, Chiyoda-ku Kudanshita 8th floor, Yodobashi Akiba Building, 1-1, Kanda-hanaoka-cho, Grand Breton Café -

Kita City Flood Hazard

A B C D E F G H I J K Locality map of Kita City and the Arakawa River “Kuru-zo mark” Toda City Kawaguchi City The “Kuru-zo mark” shows places where “Marugoto A Machigoto Hazard Map” are installed. “Marugoto raka Kita City Flood Hazard Map wa Ri Machigoto Hazard Map” is signage showing flood ve r depth in the city to help people visualize the depth - In case of flooding of the Arakawa River - Adachi City of the flooding shown in the hazard map. It also Flood depth revised version May-17 Translated in April 2020 1 Itabashi City 1 provides information about evacuation centers Kita City so that people can properly evacuate in unfamiliar places. A common graphic symbol is a mark. Get prepared! Drills with the map will help you in an emergency! Nerima Flood Hazard Map City Arakawa City This Flood Hazard Map was created with the purpose of assisting the immediate evacuation Toshima City of residents in flood risk areas in the event of an overflow of the Arakawa River. Bunkyo City Taito City (Wide area evacuation) Overview of Arakawa River flood risk areas When there is a possibility of flooding in neighboring areas of Kuru-zo mark “Marugoto Machigoto Kita City due to the burst of the right levee of the Arakawa Hazard Map” signage This is the forecast, by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT), of River, Kita City will accept evacuees from other cities. actually installed inundation based on a simulation of flooding resulting from the overflow of the Arakawa River due to the assumed maximum rainfall set by the provision of the Flood Control Act (total rainfall of 632mm in 72 hours for the Arakawa River basin), and of areas where the risk of floods that cause 2 damage, including the collapse of buildings (flooding risk areas including collapse of buildings) 2 under the current development situation of Arakawa River channels and flood control facilities in the area from the mouth of the river to Fukaya City and Yorii Town in Saitama Prefecture. -

Grand Opening of Q Plaza IKEBUKURO July 19 (Fri), 10.30 Am Ikebukuro’S Newest Landmark

July 17, 2019 Tokyu Land Corporation Tokyu Land SC Management Corporation Grand Opening of Q Plaza IKEBUKURO July 19 (Fri), 10.30 am Ikebukuro’s Newest Landmark Tokyu Land Corporation (Head office: Minato-ku, Tokyo; President: Yuji Okuma; hereafter “Tokyu Land”) and Tokyu Land SC Management Corporation (Head office: Minato-ku, Tokyo; President: Toshihiro Awatsuji) will open Q Plaza IKEBUKURO at 10.30 am on July 19 (Fri) as Ikeburo’s newest landmark, based on Toshima Ward’s International City of Arts & Culture Toshima vision. As a new entertainment complex where people of all ages can have fun, enjoying different experiences all day long on its 16 stores, including a cinema complex, an arcade and amusement center, and retail and dining options, Q Plaza IKEBUKUO will create more bustle in the Ikebukuro area, which is currently being redeveloped, and will bring life to the district in partnership with the local community. ■Many products exclusive to Q Plaza IKEBUKURO and limited time services to commemorate opening Opening for the first time in the area as flagship store, the AWESOME STORE & CAFÉ will offer a lineup of products exclusive to the Ikebukuro store, including AWESOME FLY! PO!!! with three flavors to choose from and a tuna egg bacon omelette bagel. In commemoration of the opening, Schmatz Beer Dining will offer sausages developed by Takeshi Murakami, a sausage researcher with a workshop in Yamanashi, for a limited time only. It will also provide customers with one free beer and a 19% discount for table-only reservations to commemorate the opening of its 19th store. -

01 the Expansion Of

The expansion of Edo I ntroduction With Tokugawa Ieyasu’s entry to Edo in 1590, development of In 1601, construction of the roads connecting Edo to regions the castle town was advanced. Among city construction projects around Japan began, and in 1604, Nihombashi was set as the undertaken since the establishment of the Edo Shogunate starting point of the roads. This was how the traffic network government in 1603 is the creation of urban land through between Edo and other regions, centering on the Gokaido (five The five major roads and post towns reclamation of the Toshimasusaki swale (currently the area from major roads of the Edo period), were built. Daimyo feudal lords Post towns were born along the five major roads of the Edo period, with post stations which provided lodgings and ex- Nihombashi Hamacho to Shimbashi) using soil generated by and middle- and lower-ranking samurai, hatamoto and gokenin, press messengers who transported goods. Naito-Shinjuku, Nihombashi Shinsen Edo meisho Nihon-bashi yukibare no zu (Famous Places in Edo, leveling the hillside of Kandayama. gathered in Edo, which grew as Japan’s center of politics, Shinagawa-shuku, Senju-shuku, and Itabashi-shuku were Newly Selected: Clear Weather after Snow at Nihombashi Bridge) From the collection of the the closest post towns to Edo, forming the general periphery National Diet Library. society, and culture. of Edo’s built-up area. Nihombashi, which was set as the origin of the five major roads (Tokaido, Koshu-kaido, Os- Prepared from Ino daizu saishikizu (Large Colored Map by hu-kaido, Nikko-kaido, Nakasendo), was bustling with people. -

Restoration of Sumida River

Restoration of Sumida River Postwar Sumida River waterfront was occupied by factories and warehouses, was deteriorated like a ditch, and was shunned by people. At the same time, industrial and logistical structure changes sap the area’s vitality as a production base. But increasing interest in environment headed for the semi-ruined city waterfront and a possibility of its restoration emerged and city-and-river development started, thus attractive urban area was gradually created. In Asian nations with worsening river environments, Sumida River, improving after experiencing 50-year deterioration is a leading example in Asia. Key to Restoration ¾ Water quality improvement ¾ Waterfront space restoration and waterfront development (river-walk) Overview of the River Sumida River branches from Ara River at Iwabuchi, Kita Ward. It unites with many streams such as Shingashi River, Shakujii River, and Kanda River, and flows in Tokyo Bay. It flows south to north in the seven wards in lower-level eastern areas in Tokyo (Kita Ward, Adachi Ward, Arakawa Ward, Sumida Ward, Taitou Ward, Chuo Ward, and Koutou Ward). Its total length is 23.5 km, its width is about 150 m, and the basin dimension is 690.3 km2 including upstream Shingashi River. The basin population almost reaches 6.2 million. Sumida River’s water quality, though quite polluted in the high-growth period, has substantially improved by the efforts such as water Sumida River purification projects for Sumida River restoration (e.g., construction of a filtering plant in Ukima). The variety and the number of fish, water birds, and water plants have also started to increase. -

Senkawa, Takamatsu, Chihaya, Kanamecho Ikebukuro Station's

Sunshine City is one of the largest multi-facility urban complex Ikebukuro Station is said to be one of the biggest railway terminals in Tokyo, Japan. in Japan. It consists of 5 buildings, including Sunshine It contains the JR Yamanote Line, the JR Saikyo Line, the Tobu Tojo Line, the Seibu Ikebukuro Ikebukuro Station’s 60, a landmark of Ikebukuro, at its center. It is made up of Line, Tokyo Metro Marunouchi Line, Yurakucho Line, Fukutoshin Line, etc., Sunshine City shops and restaurants, an aquarium, a planetarium, indoor Narita Express directly connects Ikebukuro Station and Narita International Airport. West Exit theme parks etc., A variety of fairs and events are held at It is a very convenient place for shopping and people can get whichever they might require Funsui-hiroba (the Fountain Plaza) in ALPA. because the station buildings and department stores are directly connected, such as Tobu Department Store, LUMINE, TOBU HOPE CENTER, Echika, Esola, etc., Jiyu Gakuen Myōnichi-kan Funsui-hiroba (the Fountain Plaza) In addition, various cultural events are held at Tokyo Metropolitan eater and Ikebukuro Nishiguchi Park on the west side of Ikebukuro Station. A ten-minute-walk from the West Exit will bring you to historic buildings such as Jiyu Gakuen Myōnichi-kan, a pioneering school of liberal education for Japan’s women and designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, Rikkyo University, the oldest Christianity University, and the Former Residence of Rampo Edogawa, a leading author of Japanese detective stories. J-WORLD TOKYO Sunshine City Rikkyo University and “Suzukake-no- michi” ©尾 田 栄 一 郎 / 集 英 社・フ ジ テ レ ビ・東 映 ア ニ メ ー シ ョ ン Pokémon Center MEGA TOKYO Tokyo Yosakoi Former Residence of Rampo Edogawa Konica Minolta Planetarium “Manten” Sunshine Aquarium Senkawa, Takamatsu, NAMJATOWN Chihaya, Kanamecho Tokyo Metropolitan Theater Ikebukuro Station’s Until about 1950, there were many ateliers around this area, and young painters and East Exit sculptors worked hard. -

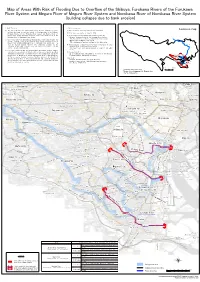

Map of Areas with Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya

Map of Areas With Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System (building collapse due to bank erosion) 1. About this map 2. Basic information Location map (1) This map shows the areas where there may be flooding powerful enough to (1) Map created by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government collapse buildings for sections subject to flood warnings of the Shibuya, (2) Risk areas designated on June 27, 2019 Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and those subject to water-level notification of the (3) River subject to flood warnings covered by this map Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System. Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) (2) This river flood risk map shows estimated width of bank erosion along the Meguro River of Meguro River System Shibuya, Furukawa rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System resulting from the maximum assumed rainfall. The simulation is based on the (4) Rivers subject to water-level notification covered by this map Sumida River situation of the river channels and flood control facilities as of the Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System time of the map's publication. (The water-level notification section is shown in the table below.) (3) This river flood risk map (building collapse due to bank erosion) roughly indicates the areas where buildings could collapse or be washed away when (5) Assumed rainfall the banks of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Up to 153mm per hour and 690mm in 24 hours in the Shibuya, Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River Furukawa, Meguro, Nomikawa Rivers basin Shibuya River,Furukawa River System are eroded. -

Shibuya City Industry and Tourism Vision

渋谷区 Shibuya City Preface Preface In October 2016, Shibuya City established the Shibuya City Basic Concept with the goal of becoming a mature international city on par with London, Paris, and New York. The goal is to use diversity as a driving force, with our vision of the future: 'Shibuya—turning difference into strength'. One element of the Basic Concept is setting a direction for the Shibuya City Long-Term Basic Plan of 'A city with businesses unafraid to take risks', which is a future vision of industry and tourism unique to Shibuya City. Each area in Shibuya City has its own unique charm with a collection of various businesses and shops, and a great number of visitors from inside Japan and overseas, making it a place overflowing with diversity. With the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games being held this year, 2020 is our chance for Shibuya City to become a mature international city. In this regard, I believe we must make even further progress in industry and tourism policies for the future of the city. To accomplish this, I believe a plan that further details the policies in the Long-Term Basic Plan is necessary, which is why the Industry and Tourism Vision has been established. Industry and tourism in Shibuya City faces a wide range of challenges that must be tackled, including environmental improvements and safety issues for accepting inbound tourism and industry. In order to further revitalize the shopping districts and small to medium sized businesses in the city, I also believe it is important to take on new challenges such as building a startup ecosystem and nighttime economy. -

Ministry of the Environment

List of Public Service Corporations under the Jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Environment ●Public Service Corporations (selected) (As of April 2001) Name of the corporation Address of the main office Telephone number <Under supervision of the Minister’s Secretariat> Environmental Information Center 8F, Office Toranomon1Bldg., 1-5-8 Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0001 03-3595-3992 Earth, Water and Green Foundation 6F, Nishi-shinbashi YK Bldg., 1-17-4 Nishi-shinbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0003 03-3503-7743 <Under supervision of the Waste Management and Recycling Department> Ecological Life and Culture Organization (ELCO) 6F, Sunrise Yamanishi Bldg., 1-20-10 Nishi-shinbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0003 03-5511-7331 Japan Environmental Sanitation Center 10-6 Yotsuya-kamicho, Kawasaki-ku, Kawasaki-shi, Kanagawa Prefecture 210-0828 044-288-4896 The National Federation of 4F, Daini-AB Bldg., 3-1-17 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 106-0032 03-3224-0811 Industrial Waste Management Associations Japan Industrial Waste Technology Center 2F, Nihonbashi Koa Bldg., 2-8-4 Nihonbashi-horidomecho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 103-0012 03-3668-6511 Japan Industrial Waste Management Foundation Sakura Shinbashi Bldg., 2-6-1 Shinbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0004 03-3500-0271 All Japan Private Sewerage Treatment Association 7F, Tokyo Yofuku Kaikan, 13 Ichigaya-hachimancho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-0844 03-3267-9757 Japan Education Center of Environmental Sanitation 2-23-3 Kikukawa, Sumida-ku, Tokyo 130-0024 03-3635-4880 Waste Water Treatment Equipment Engineer Center Kojimachi 4-chome Bldg., 4-3 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0083 03-3237-6591 Japan Sewage Works Association 1F, Nihon Bldg., 2-6-2 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0004 03-5200-0811 Japan Waste Management Association 7F, IPB Ochanomizu, 3-3-11 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033 03-5804-6281 Japan Sewage Treatment Plant Operation and 5F, Sakura Bldg., 1-3-3 Uchikanda, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 101-0047 03-5281-9291 Maintenance Association, INC. -

JCP-Psychotherapists (Japanese Certificate for Psychotherapy)

JCP-Psychotherapists (Japanese Certificate for Psychotherapy) Last Name First Name Title Postal Code City Street Country Email Fukuhara Taihei Dr. 1100005 Tokyo Kurein Bld. 3F, Ueno 6-6-2, Taito-ku Japan Fusako Enokido Prof. 9200293 Ishikawa Daigaku 1-1, Uchinada-machi, Kahoku-gun Japan [email protected] Grimes Andrew Dr. 171-0022 Tokyo SK Bld. 10F, Minami-ikebukuro 2-16-4, Japan [email protected] Toshima-ku Higuchi Shoichi 1800006 Tokyo Naka-cho 1-13-1, 2F, Musahino-Shi Japan Hitomi Kazuhiko Prof. 589-8511 Osaka Ohno-higashi 377-2, Osaka-sayami-shi Japan [email protected] Hozumi Noboru Dr. 171-0022 Tokyo Towa bld. I-26-4, Toshim-ku Japan [email protected] Ichikawa Mitsuhiro Dr. 160-0004 Tokyo Nakamura Bld. 8F, Yotsuya 1-2, Shinjuku- Japan [email protected] ku Ikuma Shigeru Dr. 1500001 Tokyo Jingumae 2-31-9, Shibuya-ku Japan [email protected] Inomata Johji Dr. 254-0035 Kanaga Miyanomae 1-8-12, Hiratsuka-shi Japan wa Ito Takao Prof. 171-0022 Tokyo SK Bld.10F, Minami-ikebukuro 2-16-4, Japan [email protected] Toshima-ku Iwasaki Tetsuya Prof. 277-0005 Chiba Kashiwa 1225-6, Kashiwa-shi Japan Kamibepp Kiyoko Prof. 113-0033 Tokyo Hongo 7-3-1, Bunkyo-ku Japan [email protected] u Katayama Mutsue Dr. 171-0022 Tokyo SK Bld. 10F, Minami-ikebukuro 2-16-4, Japan [email protected] Toshima-ku Kawahara Ryuzo Prof. 683-0826 Tottori Nishi-machi 36-1, Yonago-shi Japan [email protected] u.ac.jp Kimura Junko Dr. -

Mapping Seasonal Tree Canopy Cover and Leaf Area Using Worldview-2/3 Satellite Imagery: a Megacity- Scale Case Study in Tokyo Urban Area

Supplementary Material Mapping seasonal tree canopy cover and leaf area using WorldView-2/3 satellite imagery: A megacity- scale case study in Tokyo urban area Yutaka Kokubu 1,2,*, Seiichi Hara 3 and Akira Tani 2 1 Tokyo Metropolitan Research Institute for Environmental Protection, 1-7-5, Shinsuna, Koto-ku, Tokyo, 136- 0075, Japan 2 Department of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Shizuoka, 52-1 Yada, Suruga-ku, Shizuoka 422-8526, Japan 3 NTT Data CCS Corporation, 4-12-1 Higashishinagawa, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo, 140-0002, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected] Table S1. Comparison of the vegetation land cover for each 23 municipalities in Tokyo special wards estimated by aerial photograph interpretation (Tokyo GWC-ratio data), and WorldView-2/3 imagery classification (this study). * The numbers in parentheses show the coverage ratio in the shadow area. Main location Land coverage ratio Municipality Difference Tokyo GWC- WV-2/3 data Area (%) Image No. in ratio data (Image classification result) (Special ward) Figure 2 (1) Tree canopy Vegetation* (2) Tree canopy* Grass* (2) – (1) Nerima-ku (1) and (2) 48.1 km2 17.3% 23.7 (2.9) % 14.4 (1.8) % 9.3 (1.2) % −2.9% Itabashi-ku (2) 32.1 km2 14.5% 20.0 (2.3) % 10.0 (1.2) % 10.0 (1.2) % −4.5% Toshima-ku (2) 13.0 km2 10.2% 13.0 (1.9) % 8.0 (1.2) % 5.0 (0.7) % −2.2% Suginami-ku (2) 34.1 km2 18.8% 23.7 (3.5) % 15.8 (2.3) % 8.0 (1.2) % −3.0% Nakano-ku (2) 15.6 km2 13.3% 16.3 (2.3) % 10.1 (1.4) % 6.1 (0.9) % −3.2% Setagaya-ku (2) 58.0 km2 18.7% 25.5 (3.2) % 15.2 (1.9) % 10.3 (1.3) % -

Now(PDF:1427KB)

Okutama Minumadai- Okutama Town Shinsuikoen Ome City Yashio Ome IC Nishi- Ome Takashimadaira Adachi Tokorozawa Ward Wakoshi Daishi- Matsudo Okutama Lake Kiyose City Mae Rokucho Mizuho Town Shin- Akitsu Narimasu Akabane Akitsu Kita-Ayase Nishi-Arai Hakonegasaki Kanamachi Hamura Higashimurayama Itabashi Ward City Tama Lake Kita Ward Higashimurayama City Hikarigaoka Ayase Shibamata Higashiyamato Kumano- Kita- Higashikurume Oji Mae Senju Katsushika Hinode Town Musashimurayama City Nerima Ward Arakawa City Hibarigaoka Ward City Kamikitadai Shakujiikoen Kotakemukaihara Ward Keisei-Takasago Kodaira Toshimaen Toshima Aoto the changing Musashi-itsukaichi Hinode IC Fussa City Yokota Ogawa Nishitokyo City Ward Air Base Tamagawajosui Nerima Nishi- Tamagawajosui Kodaira City Tanashi Ikebukuro Nippori Akiruno City Ichikawa Tachikawa City Kamishakujii Nippori Haijima Bunkyo Taito Ward Akiruno IC Saginomiya Moto-Yawata Showa Kinen Ward face of tokyo Park Nakano Ward Takadanobaba Shin-Koiwa Kokubunji Koganei City Musashino City Ueno City Ogikubo Nakano Musashi-Sakai Mitaka Kichijoji Sumida Ward Akishima City Nishi-Kokubunji Nishi-Funabashi Kagurazaka Akihabara Kinshicho Hinohara Village Kokubunji Suginami Ward Tachikawa Kunitachi Nakanosakaue Shinjuku Ward Ojima Mitaka City Edogawa Ward City Kugayama Shinjuku Chiyoda Ward Sumiyoshi Hachioji-Nishi IC Honancho Fuchu City Akasaka Tokyo Funabori Tokyo, Japan’s capital and a driver of the global economy, is home Meiji Detached Fuchu Yoyogi- Shrine Hino City Chofu Airport Chitose- Meidai-Mae Palace Toyocho to 13 million people. The city is constantly changing as it moves Hachioji City Uehara Shinbashi Takahatafudo Fuchu- Karasuyama Shibuya Koto Ward Kasai Honmachi Shimotakaido steadily toward the future. The pace of urban development is also Keio-Hachioji Ward Urayasu Shimokitazawa Shibuya Chofu Kyodo Hamamatsucho Toyosu Yumenoshima accelerating as Tokyo prepares for the Olympic and Paralympic Hachioji Gotokuji Naka- Minato Chuo Park Kitano Hachioji JCT Tama Zoological Seijogakuen- Meguro Ward Ward Games in 2020 and beyond.