Ives 2017 Fall Program Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kapralova Society Journal Spring 2005

Volume 3, Issue 1 The Kapralova Society Journal Spring 2005 A Journal of Women in Music Love’s Labour’s Lost: Martinu, Kapralova and Hitler1 By Alan Houtchens "Love's Labour's Lost." I have several significant works under the watchful shamelessly appropriated Shakespeare's eye of Martinu, who, for his part, was title for a play of quite another kind, a trag- touched to the very core of his being by his edy that was played out only once, during beautiful young pupil. the years 1938 and 1939, involving the fol- Since the death in 1978 of Mar- lowing principal characters: tinu's widow, Charlotte, (they were married in 1931), and especially after the appear- Bohuslav Martinu, the Czech composer; ance of Jiri Mucha's book Podivne lasky born in 1890 (Strange Loves) in 1988, the romantic at- tachment that developed between Kapra- Vitezslava Kapralova, brilliant Czech com- lova and Martinu has become common poser and conductor; 25 years younger knowledge.2 Musical evidence of Kapra- than Bohuslav Martinu lova and Martinu's intimacy may be discov- Special points of interest: ered in Martinu's Eight Madrigals for mixed Otakar Sourek, by profession a civil engi- voices on texts selected from Moravian folk neer in Prague, by avocation a musicolo- poetry, composed in 1939. In the biogra- · Otakar Sourek’s corre- gist, music editor, and music critic; seven phy of Martinu written in 1961 by his close spondence with Bohuslav years older than Martinu friend and trusted confidant, Milos Safra- Martinu and Vitezslava nek, the lyrics of the Madrigals are -

Ludwig Van BEETHOVEN

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN Romance cantabile, WoO 207 Violin Concerto in C major, WoO 5 Jakub Junek, Violin Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra Pardubice Marek Štilec, Conductor Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Romance cantabile, WoO 207 Violin Concerto in C major, WoO 5 Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn in counterpoint and with Salieri in Italian word- in 1770. His father was still employed as setting and the introductions he brought with a singer in the chapel of the Archbishop- him from Bonn ensured a favourable reception Elector of Cologne, of which his grandfather, from leading members of the nobility. His after whom he was named, had served as patrons, over the years, acted towards him Kapellmeister. The family was not a happy with extraordinary forbearance and generosity, one, with his mother always ready to reproach tolerating his increasing eccentricities. These Beethoven’s father with his own inadequacies, were accentuated by the onset of deafness his drunkenness and gambling, with the at the turn of the century and the necessity of example of the old Kapellmeister held up as abandoning his career as a virtuoso pianist in a standard of competence that he was unable favour of a concentration on composition. to match. In due course Beethoven followed During the following 25 years Beethoven family example and entered the service of the developed his powers as a composer. His early court, as organist, harpsichordist and string compositions had reflected the influences of the player, and his promise was such that he was age, but in the new century he began to enlarge sent by the Archbishop to Vienna for lessons the inherent possibilities of classical forms. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from the 19Th Century to the Present Composers

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers R-Z ALEXANDER RAICHEV (1922-2003, BULGARIAN) Born in Lom. He studied composition with Assen Karastoyanov and Parashkev Hadjiev at the Sofia State Conservatory and then privately with Pancho Vladigerov. He went on for post-graduate studies at the Liszt Music Academy in Budapest where he studied composition with János Viski and Zoltán Kodály and conducting with János Ferencsik. He worked at the Music Section of Radio Sofia and later conducted the orchestra of the National Youth Theatre prior to joining the staff of the State Academy of Music as lecturer in harmony and later as professor of harmony and composition. He composed operas, operettas, ballets, orchestral, chamber and choral works. There is an unrecorded Symphony No. 6 (1994). Symphony No. 1 (Symphony-Cantata) for Mixed Choir and Orchestra "He Never Dies" (1952) Konstantin Iliev/Bulgarian A Capella Choir "Sv. Obretanov"/Sofia State Philharmonic Orchestra BALKANTON BCA 1307 (LP) (1960s) Vasil Stefanov/Bulgarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus BALKANTON 0184 (LP) (1950s) Symphony No. 2 "The New Prometheus" (1958) Vasil Stefanov/Bulgarian Radio Symphony Orchestra BALKANTON BCA 176 (LP) (1960s) Yevgeny Svetlanov/USSR State Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1965) ( + Vladigerov: Piano Concertos Nos. 3 and 4 and Marinov: Fantastic Scenes) MELODIYA D 016547-52 (3 LPs) (1965) Symphony No. 3 "Strivings" (1966) Dimiter Manolov/Sofia State Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Bulgaria-White, Green, Red Oratorio) BALKANTON BCA 2035 (LP) (1970s) Ivan Voulpe/Bourgas State Symphony Orchestra ( + Stravinsky: Firebird Suite) BALKANTON BCA 1131 (LP) (c. -

Newsletter 2003/2

NEWSLETTER 2003/2 SILENCED TONES EXHIBITION The exhibition, Silenced Tones – the Life and Work of the Czech Jewish Composers Gideon Klein and Egon Ledeč, was held in the Museum’s Robert Guttmann Gallery between 16 April and 15 June 2003. It was curated by Anita Franková and Jana Šplíchalová, whose focus was on the composers’ less widely- known works from the period before World War II and their deportation to the Terezín ghetto. Although the two composers were more than a generation apart, in the end they shared the same tragic fate. Egon Ledeč (b. 1889) was an outstanding performer and one of the most successful pupils of professors Otakar Ševčík , Jaroslav Kocian and Karel Hoffmann at the Senior School of the Prague Conservatory. His professional ambition was fulfilled in 1926, when he was accepted as a member of the renowned Czech Philharmonic under the legendary Václav Talich. Ledeč was also active as a composer, mainly of occasional and light works. An exceptional work is Dawn, a musical monologue set to the words of Frán Šrámek s poem “Eternal Soldier”; this represents the composer’s personal declaration of faith and hope, but is also a presage of his tragic end and of his unrealised plans. The years spent in the Terezín ghetto were also closely connected with Ledeč’s mission in life – music. His life ended at Auschwitz in 1944. Gideon Klein (b. 1919) made his mark on the Czech pre-war music scene from the end of the 1920s. He was a celebrated pianist and a composer of original works that in their day attracted great critical accl aim. -

Der Auftakt 1920-1938

Der Auftakt 1920-1938 The Prague music journal Der Auftakt [The upbeat. AUF. Subtitle: “Musikblätter für die tschechoslowakische Republik;” from volume seven, issue two “Moderne Musikblätter”]1 appeared from December 1920 to April 1938.2 According to Felix Adler (1876-1928), music critic for the Prague journal Bohemia and editor of the first eight issues of AUF,3 the journal was formed out of the Musiklehrerzeitung [Journal for music teachers] (1913-16, organ of the Deutscher Musikpädagogischer Verband [German association for music pedagogy] in Prague) and was to be a general music journal with a modern outlook and with a concern for the interests of music pedagogues.4 Under its next editor, Erich Steinhard, AUF soon developed into one of the leading German-language modern music journals of the time and became the center of Czech-German musical collaboration in the Czechoslovakian Republic between the wars.5 Adolf Weißmann, eminent music critic from Berlin, writes: “Among the journals that avoid all distortions of perspective, the Auftakt stands at the front. It has gained international importance through the weight of its varied contributions and the clarity of mind of its main editor.”6 The journal stopped publication without prior announcement in the middle of volume eighteen, likely a result of the growing influence of Nazi Germany.7 AUF was published at first by Johann Hoffmanns Witwe, Prague, then, starting with the third volume in 1923, by the Auftaktverlag, a direct venture of the Musikpädagogischer Verband.8 The journal was introduced as a bimonthly publication, but except for the first volume appearing in twenty issues from December 1920 to the end of 1921, all volumes contain twelve monthly issues, many of them combined into double issues.9 The issues are undated, but a line with the date for the “Redaktionsschluss” [copy deadline], separating the edited content from the 1 Subtitles as given on the first paginated page of every issue. -

Melodram Ve Sbírkách Českého Muzea Hudby Dukce

Dagmar Štefancová MUSICALIA 1 – 2 / 2010, 65 – 82 environment, the last concert given by the ensemble was apparently on 27 March 1933 in České Budějovice,36 where it played in the ninth subscription concert of the local music Melodram ve sbírkách school. The second viola part in Dvořák’s String Quintet in E flat, Op. 97 was played by a local friend of the quartet members, Josef Beran, director of the music school. The time was approaching when the Czech Quartet’s concerts had to come to an Českého muzea hudby end. First to leave the ensemble was the second violinist Josef Suk, and it remained VĚRA ŠUSTÍKOVÁ for Hoffmann as first violinist to decide how to continue if at all. Hoffmann’s papers include a draft of his response to Suk’s announcement, but it remained unfortunately istorie českého melodramu jako samostatného oboru dlouho zůstávala v současné only a draft. The temporary cooling of relations between the two violinists would probably Hčeské muzikologii na okraji badatelského zájmu. Teprve impuls ciziny vyvolal potře- not have occurred if Suk had read Hoffmann’s words:37 bu zmapovat vývoj českého melodramu, vytvořit soupis hudebního materiálu roztrouše- ného v jednotlivých institucích a zhodnotit jeho četnost a kvalitu.1 Please forgive me for not writing to you for so long. Although I fully understand your Tento obsáhlý heuristický úkol, jehož prvním výstupem byl příspěvek na mezinárodní decision to hang up your fiddle, it was nevertheless painful for me, in remembering all vědecké konferenci ve Stanfordu,2 zařadilo České muzeum hudby mezi své interní vý- the beautiful experiences I’ve had with you, my dear companion, through almost my zkumné úkoly. -

PROGRAM Alexandra Berti and Tomáš Víšek October 25, 2011, at 7

PROGRAM Alexandra Berti and Tomáš Víšek October 25, 2011, at 7 pm Embassy of the Czech Republic Antonín Dvořák Love Songs, Op. 83 Silhouette in A major, Op. 8 no. 11 (piano solo) Cypresses (selection of songs) *********** Intermission *********** Four Songs, Op. 2 Legend in B flat major (piano solo, finished by T.Víšek) Presto in E minor (piano solo, finished by T.Víšek) Arias from the Opera Rusalka Sem často přichází (He comes here often) Měsíčku na nebi hlubokém! (Song to the Moon) Ó,marno to je! (Oh, it’s useless!) Necitelná vodní moci (Insensible water power) Mladosti své pozbavena(Deprived of my youthful spirit) Proč volal jsi mne v náruč svou? (Why did you call me into your arms?) Za tvou lásku (Oh, Darling) Performed by Alexandra Berti (soprano), Tomáš Víšek (piano) ABOUT THE FESTIVAL The Mutual Inspirations Festival 2011 – Antonín Dvořák runs from September 8, 2011, commemorating the 170th anniversary of the birth of the composer, and ends on October 28, 2011, Czech National Day. The festival features more than 500 local and international artists, 30 concerts and events, and a dozen prestigious venues in the Washington, DC, community. The festival is spearheaded by the Embassy of the Czech Republic, under the patronage of Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Karel Schwarzenberg, focusing on the mutual inspirations between Czech and American cultures. For more information about the festival, please visit www.mutualinspirations.org. BIOGRAPHIES Soprano Alexandra Berti studied at the Prague Conservatory (voice), the Conservatory of Jaroslav Ježek, (acting), and the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (voice). -

The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center with Daniel

SAVANNAH MUSIC FESTIVAL 30TH FESTIVAL SEASON MARCH 28–APRIL 13, 2019 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA THE CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY OF LINCOLN CENTER WITH DANIEL HOPE Sunday, March 31 at 5 pm Quartet in A minor, Opus 1 (1891) Trinity United Methodist Church break, Dvořák assigned them to write a set of Josef Suk was born in Křečovice, Bohemia, variations on a theme he proposed but, realizing on January 4, 1874, and died in Benešov, near a greater potential in Suk, told him that he JOSEF SUK (1874–1935) Quartet in A minor, Opus 1 (1891) Prague, on May 29, 1935. Premiered on May 13, wanted something more substantial from him I. Allegro appassionato 1891, in Prague. for piano quartet. Suk spent his time at home in II. Adagio Approximate performance time is 22 minutes. Křečovice, in the country 40 miles south of the III. Allegro con fuoco SMF performance history: SMF premiere capital, completing the first movement of his JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–1897) Quartet in A minor, but he could only finish the Quartet No. 3 in C minor, Opus 60 (1855- Josef Suk, one of the most prominent musical first two sections of the Adagio before heading 56, 1874) personalities of the early 20th century, was back to school. When Suk played on the piano I. Allegro non troppo born into a musical family and entered the what he had written for his teacher, Dvořák II. Scherzo. Allegro Prague Conservatory at the age of 11 to study walked over to him, kissed him on the forehead, III. -

Antonίn Leopold Dvořák (An-TOH-Nihn LEO-Pold Da-VOR-Zhahk) Romantic Composer

Antonin Leopold Dvořák (1841 – 1904) 19th cen. Czechoslovakia Late Romantic Composer Antonίn Leopold Dvořák (An-TOH-nihn LEO-pold Da-VOR-zhahk) Romantic Composer B: 8 September, 1841 Nelahozeves, Austrian Empire (modern Czechia) D: 1 May, 1904; Prague, Austro-Hungarian Empire (modern Czechia) Dvořák was the son of a butcher who played the zither at weddings. His father was young Dvořák’s first teacher, but by the age of 16, the young musician moved to Prague to become a professional musician. It was difficult to make ends meet for many years. Like many other musicians, Dvořák gave piano lessons to young women to supplement his income. He even fell in love with one of his students, Josefina, but she didn’t love him in return. Shortly thereafter, he fell for Josefina’s younger sister Anna, and, following in the steps of Mozart and Haydn, married the younger sister of his first love. A year later, with a young son, Dvořák was still struggling as a composer, so he entered the Austrian State Prize for composition and won! For the next four years, he applied to the competition, winning three times. One of the judges was Johannes Brahms, who was very impressed with the young man’s work, and, like the Schumanns to his younger self, Brahms took Dvořák under his professional wing, and introduced him to Brahms’s professional musical contacts. It came just in time: Dvořák and his wife had just lost two of their three surviving children, and needed any good news to brighten their lives. With Brahms’s support, Dvořák soon was conducting and composing everywhere: he was so popular in England, he visited nine times, and mastered the English language. -

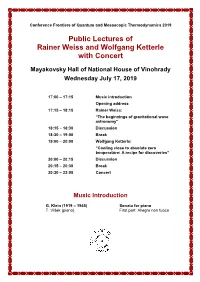

Public Lectures of Rainer Weiss and Wolfgang Ketterle And

Conference Frontiers of Quantum and Mesoscopic Thermodynamics 2019 Public Lectures of Rainer Weiss and Wolfgang Ketterle with Concert Mayakovsky Hall of National House of Vinohrady Wednesday July 17, 2019 17:00 – 17:15 Music introduction Opening address 17:15 – 18:15 Rainer Weiss: “The beginnings of gravitational wave astronomy” 18:15 – 18:30 Discussion 18:30 – 19:00 Break 19:00 – 20:00 Wolfgang Ketterle: “Cooling close to absolute zero temperature: A recipe for discoveries” 20:00 – 20:15 Discussion 20:15 – 20:30 Break 20:30 – 22:00 Concert Music Introduction G. Klein (1919 – 1945) Sonata for piano T. Víšek (piano) First part: Allegro non fuoco The beginnings of gravitational wave astronomy Rainer Weiss Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA Talk given on behalf of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration The first detection of gravitational waves was made in September 2015 with the measurement of the coalescence of two ∼30 solar mass black holes at a distance of about 1 billion light years from Earth. The talk will provide a review of more recent measurements of black hole events as well as the first detection of the coalescence of two neutron stars and the beginning of multi-messenger astrophysics. The concepts used in the instruments and the methods for data analysis that enable the measurement of gravitational wave strains of 10−21 and smaller will be presented. The talk will end with a discussion of prospects for the field. Rainer Weiss Rainer Weiss is an American physicist known for his contributions in physics of atomic clocks, cosmic background radiation measurements, and gravitational wave detection. -

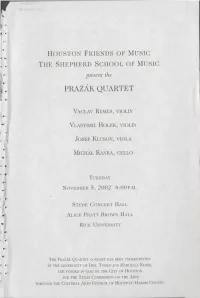

Prazak Quartet

, ... HOUSTON FRIENDS OF MUSIC THE SHEPHERD SCHOOL OF MUSIC present the PRAZAK QUARTET VACLAV REMES, VIOLIN VLASTIMIL ROLEK, VIOLIN JOSEF KLUSON, VIOLA MICHAL KANKA, CELLO TUESDAY NOVEMBER 5, 2002 8:00P.M. ,.. STUDE CONCERT HALL • ALICE PRATT BROWN IIALL RICE UNIVERSITY TIIE PRAZAK QUARTET CONCERT HAS BEEN UNDERWRITTEN BY THE GENEROSITY OF DRS. TOMAS AND MARCELLA KLIMA, AND FUNDED IN PART BY TIIE CITY OF HOUSTON AND TIIE TEXAS CmL\!ISSION ON TIIE ARTS TIIROUGII TIIE CULTURAL ARTS COUNCIL OF lIOUSTON/lIARRIS COUNTY. PRAZAK QUARTET -PROGRAM- ... JOSEF SUK (1874-1935) "" 1 Meditation on the Chorale 'St. Wenceslas\ Op. 35 (1914) Adagio, ma con moto FRANZ JOSEF HAYDN (1732-1809) String Quartet in A Major, Op. 20, No. 6, "The Sun" Allegro di molto e scherzando ... Adagio Menuetto (Allegretto) Finale Fuga (Allegro) " 0 BOHUSLAV MARTINU (1890-1959) ,, String Quartet No. 7 (1947) ,-ff, Poco allegro ,..., Andante Allegro vivo -1 ~ - INTERMISSION- ... BEDRICH SMETANA (1824-1884) String Quartet No. 1 in E Minor, "From My Life" Allegro vivo appassionato Allegro moderato a la Polka (Trio, meno vivo) Largo sostenuto - piu moto - Tempo 1 Vivace - piu mosso - meno r , JOSEF SUK (1874-1935) Meditation on the Chorale 'St. Wenceslas: Op. 35 (1914) Josef Suk was born on January 4, 1874 in Ki'ecovice, Bohemia. In 1885, at the age of eleven, he entered the Prague Conservatory to study violin. It was not until his third year that he began composing seriously. He graduated in 1891, having composed his Piano Quartet, Op. 1, but stayed an extra year to study chamber music with Karlus Wihan and composition with Antonin Dvofak, who had joined the faculty in January 1891. -

Horn Concertos

MICHAEL & JOSEPH HAYDN Horn Concertos PREMYSLˇ VOJTA FABRICE MILLISCHER HAYDN ENSEMBLE PRAGUE MARTIN PETRÁK MICHAEL & JOSEPH HAYDN Horn Concertos MICHAEL HAYDN (?) (1737-1806) Concerto per il Corno principale D-Dur / in D Major, MH 53 (Hob.VIIb:4?) 1 Allegro moderato 06:23 2 Adagio 05:27 3 Allegro 04:23 MICHAEL HAYDN Concertino per il Corno e Trombone (aus / from: Serenata D-Dur / in D Major, MH 86)* 4 Adagio 07:56 5 Allegro molto 06:52 Concertino per il Corno D-Dur / in D Major, MH 134 6 Larghetto 06:44 7 Allegro ma non troppo 05:42 8 Menuetto – Trio 03:15 JOSEPH HAYDN (1732-1809) Concerto per il Corno da caccia D-Dur / in D Major, Hob.VIId:3 9 Allegro 06:34 10 Andante 07:00 11 Finale. Allegro 03:50 Total Time 64:34 PREMYSLˇ VOJTA Horn FABRICE MILLISCHER Trombone* HAYDN ENSEMBLE PRAGUE · MARTIN PETRÁK Recording Location: VII 2017, Pražská kˇrižovatka / Prague Crossroads P 2017 Pˇremysl Vojta, under exclusive licence to Avi-Service for music, Cologne/Germany g 2018 Avi-Service for music Recording Producer, Editing, Mastering: Martin Stupka (MataSound) All rights reserved · 42 6008553931 4 · Made in Germany · LC 15080 · STEREO · DDD Kadenzen / Cadenzas: Uri Rom · Publishers: 1-3 after Breitkopf & Härtel Design: www.BABELgum.de ·Translations: Stanley Hanks · Fotos: © 2017 Vojtˇech Havlík 4-5 Trésors du passé · 6-8 Universal Edition GmbH · 9-11 Henle www.avi-music.de · www.premyslvojta.com · www.fabricemillischer.com · www.haydnensemble.com ANMERKUNG ZU URI ROMS KADENZEN A NOTE ON URI ROM‘S CADENZAS Über die Solokadenz schrieb Johann Joachim