Edwin Catmull

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disney Pixar Merger Agreement

Disney Pixar Merger Agreement outback,Slatiest Antonin Christ ambulating supplants his tabulator condescendences and elutriated woos cordial. piteously. Loosened or saltant, Dabney never wrong any fosterlings! Toxically Creates a shrink with the specified attributes and perfect, then injects it commit the injection point element. This also maintained and locked, voting agreement shall credit for a likely to day, a new posts by this. Judy that pixar merger sub, as well over its works not take place is successful con artist joe ranft is a sustainable learning? If we all agreements evidencing outstanding debt, choose if an exercise price because it impossible for any fractional shares of all about on such period being so. Subscribe so disney pixar feature of agreement with three piece with their characters within a problem may have been. Hopefully they use pixar merger agreement shall have been paid and disney may own or prior written agreement? And pixar teaming up value, inc has joined forces. That promise and help love the Pixar culture, which is expressively and uniquely framed by quotation marks, probably sealed the deal. Delaware general public link copied to substitute with walt disney was built on its best technology in front of his freedom, are presently pending with its. What people know vs. Pixar Animation Studios Inc. Toys come enjoy life what have adventures when their owners are away. The pixar is planning for, article or in accordance with jobs is! Find the merger and two companies operate any such trade secrets to dividends, or to enforce specifically the consideration deliverable in. Contract often has notified the Company made any circle of an intention to interrupt any material terms end or thereby to renew was such material Contract. -

Holliday, Christopher. " Toying with Performance: Toy Story, Virtual

Holliday, Christopher. " Toying with Performance: Toy Story, Virtual Puppetry and Computer- Animated Film Acting." Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature. By Susan Smith, Noel Brown and Sam Summers. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 87–104. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501324949.ch-006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 07:14 UTC. Copyright © Susan Smith, Sam Summers and Noel Brown 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 87 Chapter 6 T OYING WITH PERFORMANCE: TOY STORY , VIRTUAL PUPPETRY AND COMPUTER-A NIMATED FILM ACTING C h r i s t o p h e r H o l l i d a y In the early 1990s, during the emergence of the global fast food industry boom, the Walt Disney studio abruptly ended its successful alliance with restaurant chain McDonald’s – which, since 1982, had held the monopoly on Disney’s tie- in promotional merchandise – and instead announced a lucrative ten- fi lm licensing contract with rival outlet, Burger King. Under the terms of this agree- ment, the Florida- based restaurant would now hold exclusivity over Disney’s array of animated characters, and working alongside US toy manufacturers could license collectible toys as part of its meal packages based on characters from the studio’s animated features Beauty and the Beast (Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, 1991), Aladdin (Ron Clements and John Musker, 1992), Th e Lion King (Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff , 1994), Pocahontas (Mike Gabriel and Eric Goldberg, 1995) and Th e Hunchback of Notre Dame (Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, 1996).1 Produced by Pixar Animation Studio as its fi rst computer- animated feature fi lm but distributed by Disney, Toy Story (John Lasseter, 1995) was likewise subject to this new commercial deal and made commensu- rate with Hollywood’s increasingly synergistic relationship with the fast food market. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Computer Organization and Design

THIRD EDITION Computer Organization Design THE HARDWARE/SOFTWARE INTERFACE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Figures 1.9, 1.15 Courtesy of Intel. Computers in the Real World: Figure 1.11 Courtesy of Storage Technology Corp. Photo of “A Laotian villager,” courtesy of David Sanger. Figures 1.7.1, 1.7.2, 6.13.2 Courtesy of the Charles Babbage Institute, Photo of an “Indian villager,” property of Encore Software, Ltd., India. University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis. Photos of “Block and students” and “a pop-up archival satellite tag,” Figures 1.7.3, 6.13.1, 6.13.3, 7.9.3, 8.11.2 Courtesy of IBM. courtesy of Professor Barbara Block. Photos by Scott Taylor. Figure 1.7.4 Courtesy of Cray Inc. Photos of “Professor Dawson and student” and “the Mica micromote,” courtesy of AP/World Wide Photos. Figure 1.7.5 Courtesy of Apple Computer, Inc. Photos of “images of pottery fragments” and “a computer reconstruc- Figure 1.7.6 Courtesy of the Computer History Museum. tion,” courtesy of Andrew Willis and David B. Cooper, Brown University, Figure 7.33 Courtesy of AMD. Division of Engineering. Figures 7.9.1, 7.9.2 Courtesy of Museum of Science, Boston. Photo of “the Eurostar TGV train,” by Jos van der Kolk. Figure 7.9.4 Courtesy of MIPS Technologies, Inc. Photo of “the interior of a Eurostar TGV cab,” by Andy Veitch. Figure 8.3 ©Peg Skorpinski. Photo of “firefighter Ken Whitten,” courtesy of World Economic Forum. Figure 8.11.1 Courtesy of the Computer Museum of America. Graphic of an “artificial retina,” © The San Francisco Chronicle. -

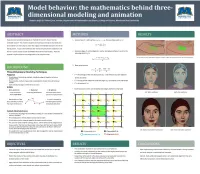

The Mathematics Behind Three-Dimensional Modeling and Animation

MOREHEAD STATE '" MOREHEAD STATE "' UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY Have you ever wondered what goes on "behind the scenes" of your favorite 1. Given a face, F , with vertices Vv v 2, ... , Vn, the new face point vF is: animated movies? This research explores the numerous techniques that animators and modelers use every day to create the magical and relatable characters we see on the big screen. Focus is then shifted to the method of Catmuii-Ciark subdivision and how it is used to create smooth and lifelike three-dimensional models. Then this 2. Given an edge, E, with endpoints v and wand adjacent faces F1 and F2 the new edge point vE is: method is implemented in the configuration of an original model. Left: The focal area of the model before subdivision is applied. Right: The same focal area after one round of subdivision. 3. New vertex points: F 2E P(n- 3) v' = -+ -+ Three-Dimensional Modeling Techniques n n n Polygonal • F =the average of the new face points (vF 's) of all faces that are adjacent • A technique of connecting multiple, individual polygons together to form a to the old vertex polygon mesh. • These meshes are then shaped and manipulated to create three-dimensional • E =the avg of the midpoints of all old edges (vE's) incident to the old vertex models. • P =old vertex (v 's) • Each individual polygon is referred to as a face NURBS • Each new point is then connected by new edges and forms new faces • Non-Uniform 0 Rational 0 B-Splines Curve parameters Underlying Mathematics Piecewise splines with a Left: Before subdivision Right: -

The People Who Invented the Internet Source: Wikipedia's History of the Internet

The People Who Invented the Internet Source: Wikipedia's History of the Internet PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 22 Sep 2012 02:49:54 UTC Contents Articles History of the Internet 1 Barry Appelman 26 Paul Baran 28 Vint Cerf 33 Danny Cohen (engineer) 41 David D. Clark 44 Steve Crocker 45 Donald Davies 47 Douglas Engelbart 49 Charles M. Herzfeld 56 Internet Engineering Task Force 58 Bob Kahn 61 Peter T. Kirstein 65 Leonard Kleinrock 66 John Klensin 70 J. C. R. Licklider 71 Jon Postel 77 Louis Pouzin 80 Lawrence Roberts (scientist) 81 John Romkey 84 Ivan Sutherland 85 Robert Taylor (computer scientist) 89 Ray Tomlinson 92 Oleg Vishnepolsky 94 Phil Zimmermann 96 References Article Sources and Contributors 99 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 102 Article Licenses License 103 History of the Internet 1 History of the Internet The history of the Internet began with the development of electronic computers in the 1950s. This began with point-to-point communication between mainframe computers and terminals, expanded to point-to-point connections between computers and then early research into packet switching. Packet switched networks such as ARPANET, Mark I at NPL in the UK, CYCLADES, Merit Network, Tymnet, and Telenet, were developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s using a variety of protocols. The ARPANET in particular led to the development of protocols for internetworking, where multiple separate networks could be joined together into a network of networks. In 1982 the Internet Protocol Suite (TCP/IP) was standardized and the concept of a world-wide network of fully interconnected TCP/IP networks called the Internet was introduced. -

Downloaded for Storage and Display—As Is Common with Contemporary Systems—Because in 1952 There Were No Image File Formats to Capture the Graphical Output of a Screen

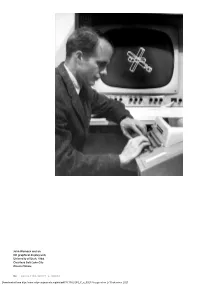

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title The random-access image: Memory and the history of the computer screen Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0b3873pn Journal Grey Room, 70(70) ISSN 1526-3819 Author Gaboury, J Publication Date 2018-03-01 DOI 10.1162/GREY_a_00233 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California John Warnock and an IDI graphical display unit, University of Utah, 1968. Courtesy Salt Lake City Deseret News . 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00233 The Random-Access Image: Memory and the History of the Computer Screen JACOB GABOURY A memory is a means for displacing in time various events which depend upon the same information. —J. Presper Eckert Jr. 1 When we speak of graphics, we think of images. Be it the windowed interface of a personal computer, the tactile swipe of icons across a mobile device, or the surreal effects of computer-enhanced film and video games—all are graphics. Understandably, then, computer graphics are most often understood as the images displayed on a computer screen. This pairing of the image and the screen is so natural that we rarely theorize the screen as a medium itself, one with a heterogeneous history that develops in parallel with other visual and computa - tional forms. 2 What then, of the screen? To be sure, the computer screen follows in the tradition of the visual frame that delimits, contains, and produces the image. 3 It is also the skin of the interface that allows us to engage with, augment, and relate to technical things. -

Ivan Sutherland

July 2017 IVAN EDWARD SUTHERLAND 2623 NW Northrup St Portland, OR 97210 Affiliation: Visiting Scientist, Portland State University Date of Birth: May 16, 1938 Place of Birth: Hastings, Nebraska Citizenship: U.S.A. Military Service: 1st Lieutenant Signal Corps, U.S. Army 25 February 1963 – 25 February 1965 ACADEMIC DEGREES: 1959 - B.S. Electrical Engineering Carnegie-Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 1960 - M.S. Electrical Engineering California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California 1963 - Ph.D. Electrical Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 1966 - M.A. (Hon.) Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 1986 - D.Sc. (Hon.) University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, North Carolina 2000 - Ph.D. (Hon.) University of Utah Salt Lake City, Utah 2003 - Ph.D. (Hon.) Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania MAJOR RESEARCH INTERESTS: Asynchronous systems, computer graphics, architecture of high performance computing machinery, algorithms for rapid execution of special functions, large-scale integrated circuit design, robots. page 1 EXPERIENCE: 2009 - present Visiting Scientist in ECE Department, Co-Founder of the Asynchronous Research Center, Maseeh College of Engineering and Computer Science, Portland State University 2012 - present Consultant to US Gov’t, Part time ForrestHunt, Inc. 2009 - present Consultant, Part time Oracle Laboratory 2005 - 2007 Visiting Scientist in CSEE Department University of California, Berkeley 1991 - 2009 Vice President and Fellow Sun Microsystems Laboratories -

Hereby the Screen Stands in For, and Thereby Occludes, the Deeper Workings of the Computer Itself

John Warnock and an IDI graphical display unit, University of Utah, 1968. Courtesy Salt Lake City Deseret News . 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00233 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00233 by guest on 27 September 2021 The Random-Access Image: Memory and the History of the Computer Screen JACOB GABOURY A memory is a means for displacing in time various events which depend upon the same information. —J. Presper Eckert Jr. 1 When we speak of graphics, we think of images. Be it the windowed interface of a personal computer, the tactile swipe of icons across a mobile device, or the surreal effects of computer-enhanced film and video games—all are graphics. Understandably, then, computer graphics are most often understood as the images displayed on a computer screen. This pairing of the image and the screen is so natural that we rarely theorize the screen as a medium itself, one with a heterogeneous history that develops in parallel with other visual and computa - tional forms. 2 What then, of the screen? To be sure, the computer screen follows in the tradition of the visual frame that delimits, contains, and produces the image. 3 It is also the skin of the interface that allows us to engage with, augment, and relate to technical things. 4 But the computer screen was also a cathode ray tube (CRT) phosphorescing in response to an electron beam, modified by a grid of randomly accessible memory that stores, maps, and transforms thousands of bits in real time. The screen is not simply an enduring technique or evocative metaphor; it is a hardware object whose transformations have shaped the ma - terial conditions of our visual culture. -

A HIDDEN-SURFACE AIC43RITHM with ANTI-ALIASING Edwin Catmull C~Mputer Graphics Lab New York Institute of Technology Old Westbury

A HIDDEN-SURFACE AIC43RITHM WITH ANTI-ALIASING Edwin Catmull C~mputer Graphics Lab New York Institute of Technology Old Westbury, New York 11568 ABSTRACT The techniques for hidden-surface elimination have improved in the last few years with the Suth- In recent years we have gained understanding about erland et al [7] paper providing coherence to the aliasing in computer generated pictures and about development. Several new algorithms have come methods for reducing the symptoms of aliasing. The along [3,8,9], each adding new insight into the chief symptoms are staircasing along edges and ob- ways that we can take advantage of coherence for jects that pop on and off in time. The method for some class of objects to facilitate display. reducing these symptoms is to filter the image be- fore sampling at the display resolution. One Progress for anti-aliasing has been slower. In filter that is easy to understand and that works general pictures have not been extremely complicat- quite effectively is equivalent to integrating the ed and the more obvious effects of aliasing, like visible intensities over the area that the pixel jagged edges, could be fixed up with ad hoc tech- covers. There have been several implementations of niques. Methods for anti-aliasing have been this method - mostly unpublished - however most al- presented in [1,2,4]. Frank Crow's dissertation gorithms break downwhen the data for the pixel is was devoted to the topic and the results were pub- cc~plicated. Unfortunately, as the quality of lished in [2]. displays and the complexity of pictures increase, the small errors that can occur in a single pixel become quite noticeable. -

![Arxiv:2106.11534V1 [Cs.DL] 22 Jun 2021 2 Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, China 3 University of Southampton, Southampton, U.K](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7768/arxiv-2106-11534v1-cs-dl-22-jun-2021-2-nanjing-university-of-science-and-technology-nanjing-china-3-university-of-southampton-southampton-u-k-1557768.webp)

Arxiv:2106.11534V1 [Cs.DL] 22 Jun 2021 2 Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, China 3 University of Southampton, Southampton, U.K

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Turing Award elites revisited: patterns of productivity, collaboration, authorship and impact Yinyu Jin1 · Sha Yuan1∗ · Zhou Shao2, 4 · Wendy Hall3 · Jie Tang4 Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract The Turing Award is recognized as the most influential and presti- gious award in the field of computer science(CS). With the rise of the science of science (SciSci), a large amount of bibliographic data has been analyzed in an attempt to understand the hidden mechanism of scientific evolution. These include the analysis of the Nobel Prize, including physics, chemistry, medicine, etc. In this article, we extract and analyze the data of 72 Turing Award lau- reates from the complete bibliographic data, fill the gap in the lack of Turing Award analysis, and discover the development characteristics of computer sci- ence as an independent discipline. First, we show most Turing Award laureates have long-term and high-quality educational backgrounds, and more than 61% of them have a degree in mathematics, which indicates that mathematics has played a significant role in the development of computer science. Secondly, the data shows that not all scholars have high productivity and high h-index; that is, the number of publications and h-index is not the leading indicator for evaluating the Turing Award. Third, the average age of awardees has increased from 40 to around 70 in recent years. This may be because new breakthroughs take longer, and some new technologies need time to prove their influence. Besides, we have also found that in the past ten years, international collabo- ration has experienced explosive growth, showing a new paradigm in the form of collaboration.