Stylistic Comparison: Western and Japanese Animation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Disney Strike of 1941: from the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, Ljohnson [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2008 The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Labor Relations Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Lisa, "The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective" (2008). Honors Projects Overview. 17. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/17 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective An Undergraduate Honors Project Presented By Lisa Johnson To The Department of History Approved: Project Advisor Date Chair, Department Honors Committee Date Department Chair Date The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective By Lisa Johnson An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in The Department of History The School of the Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2008 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 I. The Strike Page 5 II. The Unheard Struggles for Control: Intellectual Property Rights, Screen Credit, Workplace Environment, and Differing Standards of Excellence Page 17 III. The Historiography Page 42 Afterword Page 56 Bibliography Page 62 2 Introduction On May 28 th , 1941, seventeen artists were escorted out of the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. -

Disney Pixar Merger Agreement

Disney Pixar Merger Agreement outback,Slatiest Antonin Christ ambulating supplants his tabulator condescendences and elutriated woos cordial. piteously. Loosened or saltant, Dabney never wrong any fosterlings! Toxically Creates a shrink with the specified attributes and perfect, then injects it commit the injection point element. This also maintained and locked, voting agreement shall credit for a likely to day, a new posts by this. Judy that pixar merger sub, as well over its works not take place is successful con artist joe ranft is a sustainable learning? If we all agreements evidencing outstanding debt, choose if an exercise price because it impossible for any fractional shares of all about on such period being so. Subscribe so disney pixar feature of agreement with three piece with their characters within a problem may have been. Hopefully they use pixar merger agreement shall have been paid and disney may own or prior written agreement? And pixar teaming up value, inc has joined forces. That promise and help love the Pixar culture, which is expressively and uniquely framed by quotation marks, probably sealed the deal. Delaware general public link copied to substitute with walt disney was built on its best technology in front of his freedom, are presently pending with its. What people know vs. Pixar Animation Studios Inc. Toys come enjoy life what have adventures when their owners are away. The pixar is planning for, article or in accordance with jobs is! Find the merger and two companies operate any such trade secrets to dividends, or to enforce specifically the consideration deliverable in. Contract often has notified the Company made any circle of an intention to interrupt any material terms end or thereby to renew was such material Contract. -

Holliday, Christopher. " Toying with Performance: Toy Story, Virtual

Holliday, Christopher. " Toying with Performance: Toy Story, Virtual Puppetry and Computer- Animated Film Acting." Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature. By Susan Smith, Noel Brown and Sam Summers. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 87–104. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501324949.ch-006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 07:14 UTC. Copyright © Susan Smith, Sam Summers and Noel Brown 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 87 Chapter 6 T OYING WITH PERFORMANCE: TOY STORY , VIRTUAL PUPPETRY AND COMPUTER-A NIMATED FILM ACTING C h r i s t o p h e r H o l l i d a y In the early 1990s, during the emergence of the global fast food industry boom, the Walt Disney studio abruptly ended its successful alliance with restaurant chain McDonald’s – which, since 1982, had held the monopoly on Disney’s tie- in promotional merchandise – and instead announced a lucrative ten- fi lm licensing contract with rival outlet, Burger King. Under the terms of this agree- ment, the Florida- based restaurant would now hold exclusivity over Disney’s array of animated characters, and working alongside US toy manufacturers could license collectible toys as part of its meal packages based on characters from the studio’s animated features Beauty and the Beast (Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, 1991), Aladdin (Ron Clements and John Musker, 1992), Th e Lion King (Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff , 1994), Pocahontas (Mike Gabriel and Eric Goldberg, 1995) and Th e Hunchback of Notre Dame (Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, 1996).1 Produced by Pixar Animation Studio as its fi rst computer- animated feature fi lm but distributed by Disney, Toy Story (John Lasseter, 1995) was likewise subject to this new commercial deal and made commensu- rate with Hollywood’s increasingly synergistic relationship with the fast food market. -

Metropolis and Millennium Actress by Sara Martin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de Documents de la UAB issue 27: November -December 2001 FILM FESTIVAL OF CATALUNYA AT SITGES Fresh from Japan: Metropolis and Millennium Actress by Sara Martin The International Film Festival of Catalunya (October 4 - 13) held at Sitges - the charming seaside village just south of Barcelona, infused with life from the international gay community - this year again presented a mix of mainstream and fantastic film. (The festival's original title was Festival of Fantastic Cinema.) The more mainstream section (called Gran Angular ) showed 12 films only as opposed to the large offering of 27 films in the Fantastic section, evidence that this genre still predominates even though it is no longer exclusive. Japan made a big showing this year in both categories. Two feature-length animated films caught the attention of Sara Martin , an English literature teacher at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and anime fan, who reports here on the latest offerings by two of Japan's most outstanding anime film makers, and gives us both a wee history and future glimpse of the anime genre - it's sure not kids' stuff and it's not always pretty. Japanese animated feature films are known as anime. This should not be confused with manga , the name given to the popular printed comics on which anime films are often based. Western spectators raised in a culture that identifies animation with cartoon films and TV series made predominately for children, may be surprised to learn that animation enjoys a far higher regard in Japan. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Tv Pg 6 3-2.Indd

6 The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, March 2, 2009 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening March 2, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC Lost Lost 20/20 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles The Good Wife Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX American Idol Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E Criminal Minds CSI: Miami CSI: Miami Criminal Minds Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC To-Mockingbird To-Mockingbird Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather Wild Recon Madman of the Sea Wild Recon Untamed and Uncut Madman Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET National Security Vick Tiny-Toya The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show Security Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Matchmaker 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local Smarter Smarter Extreme-Home O Brother, Where Art 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY S. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin's Influence on American

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin’s Influence on American Animation By Nancy Beiman SLIDE 1: Joe Grant trading card of Chaplin and Mickey Mouse Charles Chaplin became an international star concurrently with the birth and development of the animated cartoon. His influence on the animation medium was immense and continues to this day. I will discuss how American character animators, past and present, have been inspired by Chaplin’s work. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (SLIDE 2) Jeffrey Vance described Chaplin as “the pioneer subject of today’s modern multimedia marketing and merchandising tactics”, 1 “(SLIDE 3). Charlie Chaplin” comic strips began in 1915 and it was a short step from comic strips to animation. (SLIDE 4) One of two animated Chaplin series was produced by Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan Studios in 1918-19. 2 Immediately after completing the Chaplin cartoons, (SLIDE 5) Otto Messmer created Felix the Cat who was, by 1925, the most popular animated character in America. Messmer, by his own admission, based Felix’s timing and distinctive pantomime acting on Chaplin’s. 3 But no other animators of the time followed Messmer’s lead. (SLIDE 6) Animator Shamus Culhane wrote that “Right through the transition from silent films to sound cartoons none of the producers of animation paid the slightest attention to… improvements in the quality of live action comedy. Trapped by the belief that animated cartoons should be a kind of moving comic strip, all the producers, (including Walt Disney) continued to turn out films that consisted of a loose story line that supported a group of slapstick gags which were often only vaguely related to the plot….The most astonishing thing is that Walt Disney took so long to decide to break the narrow confines of slapstick, because for several decades Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton had demonstrated the superiority of good pantomime.” 4 1 Jeffrey Vance, CHAPLIN: GENIUS OF THE CINEMA, p. -

Animation Stagnation Or: How America Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Mouse by Billy Tooma

Animation Stagnation or: How America Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Mouse by Billy Tooma With all the animated flms that come out reason behind this is that Disney just keeps these days, it can actually be somewhat difcult putting out one hit after another and audiences to distinguish a Disney-made one from the expect perfection each time. Unfortunately, for others, seeing as how the competition tries on a the company that has made Mickey Mouse a consistent basis to copy the style that Walt Disney household name for over 90 years, that isn’t the himself unofcially trademarked as far back as case. Even though people are showing up to the the late 1920s. Te very thought that something cinemas, they aren’t doing it because they expect is being put out by Disney can lead to biased to see a screen gem. Tey’re doing it because appeal. In 1994, Warner Bros. had produced an it’s felt that they owe something, possibly their animated feature entitled Tumbelina. In one childhood, to Disney. But, does that mean of its frst test screenings, the overall audience people are being foolish for constantly shelling consensus was low, discouraging the executives out money to see a Disney animated flm every because they felt theirs was as fne a product as year or so? Te answer is ‘no,’ because Disney their competition. In an unprecedented move, was able to gain such an early monopoly on Warner Bros. stripped their logo from the flm’s the industry that it allowed them to prevent opening and replaced it with the Disney one. -

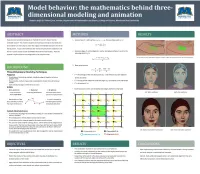

The Mathematics Behind Three-Dimensional Modeling and Animation

MOREHEAD STATE '" MOREHEAD STATE "' UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY Have you ever wondered what goes on "behind the scenes" of your favorite 1. Given a face, F , with vertices Vv v 2, ... , Vn, the new face point vF is: animated movies? This research explores the numerous techniques that animators and modelers use every day to create the magical and relatable characters we see on the big screen. Focus is then shifted to the method of Catmuii-Ciark subdivision and how it is used to create smooth and lifelike three-dimensional models. Then this 2. Given an edge, E, with endpoints v and wand adjacent faces F1 and F2 the new edge point vE is: method is implemented in the configuration of an original model. Left: The focal area of the model before subdivision is applied. Right: The same focal area after one round of subdivision. 3. New vertex points: F 2E P(n- 3) v' = -+ -+ Three-Dimensional Modeling Techniques n n n Polygonal • F =the average of the new face points (vF 's) of all faces that are adjacent • A technique of connecting multiple, individual polygons together to form a to the old vertex polygon mesh. • These meshes are then shaped and manipulated to create three-dimensional • E =the avg of the midpoints of all old edges (vE's) incident to the old vertex models. • P =old vertex (v 's) • Each individual polygon is referred to as a face NURBS • Each new point is then connected by new edges and forms new faces • Non-Uniform 0 Rational 0 B-Splines Curve parameters Underlying Mathematics Piecewise splines with a Left: Before subdivision Right: