1 the Mobilization of “Nature”: Green Collaborations, Anti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Knowledge and Customary Law in Natural Resource Management: Experiences in Yunnan, China and Haruku, Indonesia

Indigenous Knowledge and Customary Law in Natural Resource Management: Experiences in Yunnan, China and Haruku, Indonesia By He Hong Mu Xiuping and Eliza Kissya with Yanes II Indigenous Knowledge and Customary Law in Natural Resource Management: Experiences in Yunnan, China and Haruku, Indonesia Copyright @ Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) Foundation, 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the copyright holder. Editor: Ms. Luchie Maranan Design and layout: Nabwong Chuaychuwong ([email protected]) Publisher: Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) Foundation 108 Moo 5, Soi 6, Tambon Sanpranate Amphur Sansai, Chiang Mai 50210, Thailand Tel: +66 053 380 168 Fax: +66 53 380 752 Web: www.aippnet.org ISBN 978-616-90611-5-1 This publication has been produced with the financial support from the SwedBio. Sweden. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the position of AIPP or that of the Swedbio. Indigenous Knowledge and Customary Law in Natural Resource Management: Experiences in Yunnan, China and Haruku, Indonesia By He Hong Mu Xiuping and Eliza Kissya with Yanes IV Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VI ACRONYMS VII Introduction VIII Part A: Traditional Naxi Natural Resource Management and Current Policy: A Case Study at Yuhu Village, Yulong county, Yunnan, China 1 1. Basic Information about Naxi Ethnic Minority 1 1.1 The Name of Naxi Ethnic Minority 1 1.2 Population and Distribution of Naxi 1 1.3 Changes in Political Status and Social Life of Naxi People since the Founding of the PRC 3 1.4 Social and Cultural Background of Naxi 4 2. -

The Geographical Distribution of Grey Wolves (Canis Lupus) in China: a Systematic Review

ZOOLOGICAL RESEARCH The geographical distribution of grey wolves (Canis lupus) in China: a systematic review Lu WANG1,#, Ya-Ping MA1,2,#, Qi-Jun ZHOU2, Ya-Ping ZHANG1,2, Peter SAVOLAINEN3, Guo-Dong WANG2,* 1. State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Bio-resources in Yunnan and Key Laboratory for Animal Genetic Diversity and Evolution of High Education in Yunnan Province, Yunnan University, Kunming 650091, China 2. State Key Laboratory of Genetic Resources and Evolution and Yunnan Key Laboratory of Molecular Biology of Domestic Animals, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650223, China 3. Science for Life Laboratory, Department of Gene Technology, KTH-Royal Institute of Technology, Solna 17165, Sweden ABSTRACT forests of Siberia, and the frozen tundra on Ellesmere island (Mech, 1981). Despite extirpation from many parts of their The grey wolf (Canis lupus) is one of the most widely previous range over the last few hundred years, by persecution distributed terrestrial mammals, and its distribution from humans and habitat fragmentation (Hunter & Barrett, 2011; and ecology in Europe and North America are Young & Goldman, 1944), wolves still retain most of their largely well described. However, the distribution of original distributions. grey wolves in southern China is still highly The distribution and ecology of grey wolves are largely well controversial. Several well-known western literatures described in Europe and North America. However, in more stated that there were no grey wolves in southern peripheral and remote parts of their distributions, detailed China, while the presence of grey wolves across information is often lacking. In the western literature, the wolf China has been indicated in A Guide to the has generally been reported to be distributed throughout the Mammals of China, published by Princeton northern hemisphere, from N15° latitude in North America and University Press. -

Kahrl Navigating the Border Final

CHINA AND FOREST TRADE IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION: IMPLICATIONS FOR FORESTS AND LIVELIHOODS NAVIGATING THE BORDER: AN ANALYSIS OF THE CHINA- MYANMAR TIMBER TRADE Fredrich Kahrl Horst Weyerhaeuser Su Yufang FO RE ST FO RE ST TR E ND S TR E ND S COLLABORATING INSTITUTIONS Forest Trends (http://www.forest-trends.org): Forest Trends is a non-profit organization that advances sustainable forestry and forestry’s contribution to community livelihoods worldwide. It aims to expand the focus of forestry beyond timber and promotes markets for ecosystem services provided by forests such as watershed protection, biodiversity and carbon storage. Forest Trends analyzes strategic market and policy issues, catalyzes connections between forward-looking producers, communities, and investors and develops new financial tools to help markets work for conservation and people. It was created in 1999 by an international group of leaders from forest industry, environmental NGOs and investment institutions. Center for International Forestry Research (http://www.cifor.cgiar.org): The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), based in Bogor, Indonesia, was established in 1993 as a part of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) in response to global concerns about the social, environmental, and economic consequences of forest loss and degradation. CIFOR research produces knowledge and methods needed to improve the wellbeing of forest-dependent people and to help tropical countries manage their forests wisely for sustained benefits. This research is conducted in more than two dozen countries, in partnership with numerous partners. Since it was founded, CIFOR has also played a central role in influencing global and national forestry policies. -

Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau

IPP740 REV World Bank-financed Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Ethnic Minority Development Plan of the Yunnan Highway Assets Management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau July 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized EMDP of the Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Summary of the EMDP A. Introduction 1. According to the Feasibility Study Report and RF, the Project involves neither land acquisition nor house demolition, and involves temporary land occupation only. This report aims to strengthen the development of ethnic minorities in the project area, and includes mitigation and benefit enhancing measures, and funding sources. The project area involves a number of ethnic minorities, including Yi, Hani and Lisu. B. Socioeconomic profile of ethnic minorities 2. Poverty and income: The Project involves 16 cities/prefectures in Yunnan Province. In 2013, there were 6.61 million poor population in Yunnan Province, which accounting for 17.54% of total population. In 2013, the per capita net income of rural residents in Yunnan Province was 6,141 yuan. 3. Gender Heads of households are usually men, reflecting the superior status of men. Both men and women do farm work, where men usually do more physically demanding farm work, such as fertilization, cultivation, pesticide application, watering, harvesting and transport, while women usually do housework or less physically demanding farm work, such as washing clothes, cooking, taking care of old people and children, feeding livestock, and field management. In Lijiang and Dali, Bai and Naxi women also do physically demanding labor, which is related to ethnic customs. Means of production are usually purchased by men, while daily necessities usually by women. -

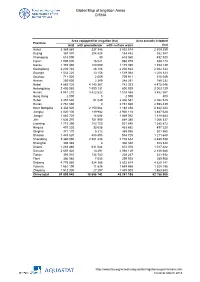

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

Human Paleodiet and Animal Utilization Strategies During the Bronze Age in Northwest Yunnan Province, Southwest China

RESEARCH ARTICLE Human paleodiet and animal utilization strategies during the Bronze Age in northwest Yunnan Province, southwest China Lele Ren1, Xin Li2, Lihong Kang3, Katherine Brunson4, Honggao Liu1,5, Weimiao Dong6, Haiming Li1, Rui Min3, Xu Liu3, Guanghui Dong1* 1 MOE Key Laboratory of Western China's Environmental System, College of Earth Environmental Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, Gansu Province, China, 2 School of Public Health, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, Gansu Province, China, 3 Yunnan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Kunming, China, 4 Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University, Providence, Rhode a1111111111 Island, United States of America, 5 College of Agronomy and Biotechnology, Yunnan Agricultural University, a1111111111 Kunming, China, 6 Department of Cultural Heritage and Museology, Fudan University, Shanghai, China a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Reconstructing ancient diets and the use of animals and plants augment our understanding OPEN ACCESS of how humans adapted to different environments. Yunnan Province in southwest China is Citation: Ren L, Li X, Kang L, Brunson K, Liu H, ecologically and environmentally diverse. During the Neolithic and Bronze Age periods, this Dong W, et al. (2017) Human paleodiet and animal region was occupied by a variety of local culture groups with diverse subsistence systems utilization strategies during the Bronze Age in and material culture. In this paper, we obtained carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotopic northwest Yunnan Province, southwest China. ratios from human and faunal remains in order to reconstruct human paleodiets and strate- PLoS ONE 12(5): e0177867. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0177867 gies for animal exploitation at the Bronze Age site of Shilinggang (ca. -

Endemic Wild Ornamental Plants from Northwestern Yunnan, China

HORTSCIENCE 40(6):1612–1619. 2005. have played an important role in world horti- culture and have been introduced to Western countries where they have been widely cul- Endemic Wild Ornamental Plants tivated. Some of the best known examples include Rhododendron, Primula, Gentiana, from Northwestern Yunnan, China Pedicularis, and Saussurea, which are all im- 1 portant genera in northwestern Yunnan (Chen Xiao-Xian Li and Zhe-Kun Zhou et al., 1989; Feng, 1983; Guan et al., 1998; Hu, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, P.R. 1990; Shi and Jin, 1999; Yang, 1956;). Many of China 650204 these ornamental species are endemic to small areas of northwestern Yunnan (e.g., Rhododen- Additional index words. horticultural potential dron russatum), therefore, their cultivation not Abstract. Northwestern Yunnan is situated in the southern part of the Hengduan Mountains, only provides for potential sources of income which is a complex and varied natural environment. Consequently, this region supports a generation, but also offers a potential form of great diversity of endemic plants. Using fi eld investigation in combination with analysis conservation management: these plants can of relevant literature and available data, this paper presents a regional ethnobotanical be used directly for their ornamental plant study of this area. Results indicated that northwestern Yunnan has an abundance of wild value or as genetic resources for plant breed- ornamental plants: this study identifi ed 262 endemic species (belonging to 64 genera and ing programs. The aims of current paper are 28 families) with potential ornamental value. The distinguishing features of these wild to describe the unique fl ora of northwestern plants, their characteristics and habitats are analyzed; the ornamental potential of most Yunnan and provide detailed information of plants stems from their wildfl owers, but some species also have ornamental fruits and those resources, in terms of their potential foliage. -

RESEARCH Petrogenesis and Tectonic Setting

RESEARCH Petrogenesis and tectonic setting of the Early Cretaceous granitoids in the eastern Tengchong terrane, SW China: Constraint on the evolution of Meso-Tethys Xiaohu He1, Zheng Liu1, Guochang Wang2, Nicole Leonard3, Wang Tao4, and Shucheng Tan1,* 1DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY, SCHOOL OF RESOURCE ENVIRONMENT AND EARTH SCIENCE, YUNNAN UNIVERSITY, KUNMING 650091, CHINA 2YUNNAN KEY LABORATORY FOR PALAEOBIOLOGY, YUNNAN UNIVERSITY, KUNMING 650091, CHINA 3RADIOGENIC ISOTOPE FACILITY, SCHOOL OF EARTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES, THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND, BRISBANE QLD 4072, AUSTRALIA 4YUNNAN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, KUNMING 650091, CHINA ABSTRACT As a result of the evolution of Meso-Tethys, Early Cretaceous granitoids are widespread in the eastern Tengchong terrane, SW China, which is considered as the southern extension of the Tibetan Plateau. These igneous rocks are therefore very important for understanding the tectonic setting of Meso-Tethys and the formation of the Tibetan Plateau. In this paper, we present new zircon U-Pb dating, whole-rock elemental, and Nd isotopic data of granitoids obtained from the eastern Tengchong terrane. Our results show that these granitoids are composed of monzogranites and granodiorites and formed at ca. 124 Ma in the Early Cretaceous. Mineralogically and geochemically, these granitoids display metaluminous nature and affinity to I-type granites, which are derived from preexisting intracrustal igneous source rocks. The predominantly negative whole-rock εNd(t) values (−10.86 to −8.64) for all samples indicate that they are derived mainly from the partial melting of the Mesoproterozoic metabasic rocks in the lower crust. Integrating previous studies with the data presented in this contribution, we propose that the Early Cretaceous granitic rocks (135–110 Ma) also belong to I-type granites with minor high fractionation. -

Nosu, Shengzha September 11

Nosu, Shengzha September 11 •Ya’an History: Nosu history is SICHUAN one of violence and Yuexi interclan warfare. For Muli • Zhaotong centuries the Nosu YUNNAN • GUIZHOU raided villages and took •Panzhihua slaves, forcing them to Scale •Wuding do manual labor. One 0 KM 160 missionary noted, “In Population in China: retaliation for the taking 800,000 (1989) of slaves, it was not 1,024,400 (2000) uncommon in the 1,285,600 (2010) Location: 1940s to see Chinese Sichuan, Yunnan, Tibet soldiers walking through Religion: Polytheism city streets carrying on Christians: 12,000 their backs large baskets filled with Nosu Overview of the heads, still dripping Shengzha Nosu with blood.”8 The Nosu Countries: China, USA region, in 1956, was Pronunciation: the last part of China to “Shung-jah-Nor-soo” Other Names: Northern Yi, come under Communist Sichuan Yi, Lolo, North Lolo, rule. In the violent Black Yi, Manchia, Mantzu, clashes ten Chinese Naso, Nuosu, Daliangshan Paul Hattaway Nosu, Shengcha Yi, Shengzha Yi troops were killed for Population Source: Location: More than one million speakers every Nosu, earning the Nosu the 800,000 (1989 Shi Songshan); of Shengzha Nosu live in southern Sichuan nickname, “Iron Peas.”9 Since the collapse Out of a total Yi population of 2 6,572,173 (1990 census); Province. Their primary locations are in of the slave system, the class structure 45 in USA1 Xide, Yuexi, Zhaojue, Ganluo, and Jinyang among the Nosu has weakened. Today even Location: S Sichuan: Daliangshan counties. Other significant communities are the former -

Cultural Revolution on the Border: Yunnan's 'Political Frontier Defence' (1969-1971)

Cultural Revolution on the Border: Cultural Revolution on the Border: Yunnan's 'Political Frontier Defence' (1969-1971) MICHAEL SCHOENHALS Abstract This paper addresses an important but so far neglected episode in the post- 1949 history of China – the impact of the so-called 'Cultural Revolution' on the country's ethnic minority populations. Specifically, it attempts to deal with the movement as it unfolded in the province of Yunnan where, at one stage, it be- came an attempt by a political leadership in the provincial capital, dominated by military officers and supported by members of the central authorities in Beijing, to alter the landscape of the ethnic minority populations along the frontier. Using information culled from local histories and contemporary sources, the pa- per traces the history of what even by the standards of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) came to be regarded as an exceptionally flawed and counterproductive policy. It foregrounds the human cost of its implementation and, for the first time, goes some way towards explaining – in more than simply general terms of labels like 'excesses' and 'ultra-leftism' – the trauma of those who survived it, a trauma that to this day still lingers in popular memory.1 Introduction During the 'Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution', China's southern frontier – where the province of Yunnan borders on Vietnam, Laos and Burma – witnessed the implementation of something called a 'political frontier defence' (zhengzhi bianfang) (PFD). As part of the Cultural Revo- lution, the PFD has left no traces in the works of historians concerned with national-level events and developments, nor has it figured in social science scholarship concerned with the organization of political power and its consequences in the 'Maoist system' (Barnouin and Yu 1993; MacFarquhar and Fairbank 1991; Yan and Gao 1996). -

Challenges of Sustaining Malaria Community Case Management in 81 Township Hospitals Along the China-Myanmar Border Region — Yunnan Province, China, 2020

China CDC Weekly Preplanned Studies Challenges of Sustaining Malaria Community Case Management in 81 Township Hospitals along the China-Myanmar Border Region — Yunnan Province, China, 2020 Wei Ding1; Shenning Lu1; Qiuli Xu1; Xuejiao Ma1; Bei Wang1; Jingbo Xue1; Xiaodong Sun2; Jianwei Xu2; Chris Cotter3; Duoquan Wang1,#; Yayi Guan1; Ning Xiao1 workforce and their challenges in the delivery of Summary malaria diagnostic and treatment services through a What is already known on this topic? structured questionnaire. The results showed that the The health workforce at township hospitals in the CCMm was satisfactory for case recognition and China-Myanmar border region has played a key role in testing by rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), while both sustaining Community case management of malaria training on malaria diagnosis and providing necessary (CCMm), while few studies have investigated their treatment for patients were insufficient, and risks of performance and challenges. instability in the malaria workforce existed. It is What is added by this report? recommended to provide regular training and intensive Sustaining CCMm in the region was subject to the supervision for the malaria workforce to identify following major challenges: insufficient training on strategies to sustain the workforce. malaria diagnosis and testing, lacking necessary and The study was conducted from July to December timely treatment for patients, and risks of instability 2020. All relevant malaria health staff (568) of all among the malaria workforce. township hospitals -

Human Pressures on Natural Reserves in Yunnan Province And

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Human Pressures on Natural Reserves in Yunnan Province and Management Implications Received: 5 October 2017 Cheng Qiu1,2,3, Jinming Hu 1,3,4, Feiling Yang1,3, Feng Liu1,3 & Xinwang Li1,3 Accepted: 8 February 2018 The analysis of status and major sources of human pressures on natural reserves (NRs) is important Published: xx xx xxxx for optimizing their management. This study selected population density, gross domestic product (GDP) density and areal percentage of human land use to reveal the human pressures of national and provincial NRs (NNRs and PNRs) in Yunnan Province, China. We calculated three types of internal and external human pressure index (HPI) and comprehensive HPI (CHPI) for NRs. Human pressures on most of NRs were slight and light, indicating that most of NRs were well protected. Human pressures on PNRs were higher than on NNRs; with respect to fve types of NRs, geological relict NRs were facing the highest human pressures, followed by wetland ecosystem NRs. Land use and population density were the main human pressures on these NRs. Yunnan Province should put the highest emphasis on three NNRs and two Ramsar site PNRs with severe CHPI, secondly pay attention to eight conservation- oriented PNRs with extreme or severe CHPI. It’s urgent for Yunnan to implement scientifc policies and measures to reduce land use and population density pressures of NRs, especially with severe and extreme CHPI, by transforming internal land use and/or implementing residents’ eco-migration. Biodiversity loss is accelerating1, and increasing human activities that contribute to the degradation of natu- ral ecological systems are the main causes2–4.