LOVELL-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML Advanced

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML advanced Sections in this Page Introduction Trojan Cycle: Cypria Iliad (Synopsis) Aethiopis Little Iliad Sack of Ilium Returns Odyssey (Synopsis) Telegony Other works on the Trojan War Bibliography Introduction and Definition of terms The so called Epic Cycle is sometimes referred to with the term Epic Fragments since just fragments is all that remain of them. Some of these fragments contain details about the Theban wars (the war of the SEVEN and that of the EPIGONI), others about the prowesses of Heracles 1 and Theseus, others about the origin of the gods, and still others about events related to the Trojan War. The latter, called Trojan Cycle, narrate events that occurred before the war (Cypria), during the war (Aethiopis, Little Iliad, and Sack of Ilium ), and after the war (Returns, and Telegony). The term epic (derived from Greek épos = word, song) is generally applied to narrative poems which describe the deeds of heroes in war, an astounding process of mutual destruction that periodically and frequently affects mankind. This kind of poetry was composed in early times, being chanted by minstrels during the 'Dark Ages'—before 800 BC—and later written down during the Archaic period— from c. 700 BC). Greek Epic is the earliest surviving form of Greek (and therefore "Western") literature, and precedes lyric poetry, elegy, drama, history, philosophy, mythography, etc. -

From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1 a Study in the Longue Durée Wikander, Ola

From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1 A Study in the Longue Durée Wikander, Ola Published in: Studies in Isaiah 2017 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wikander, O. (2017). From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1: A Study in the Longue Durée. In T. Wasserman, G. Andersson, & D. Willgren (Eds.), Studies in Isaiah: History, Theology and Reception (pp. 116- 135). (Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament studies, 654 ; Vol. 654). Bloomsbury T&T Clark. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 LIBRARY OF HEBREW BIBLE/ OLD TESTAMENT STUDIES 654 Formerly Journal of the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series Editors Claudia V. -

General Introduction Hesiod and His Poems

General Introduction Hesiod and His Poems The Theogony is one of the most important mythical texts to survive from antiquity, and I devote the first section of this translation to it. It tells of the creation of the present world order under the rule of almighty Zeus. The Works and Days, in the second section, describes a bitter dispute between Hesiod and his brother over the disposition of their father’s property, a theme that allows Hesiod to range widely over issues of right and wrong. The Shield of Herakles, whose centerpiece is a long description of a work of art, is not by Hesiod, at least most of it, but it was always attributed to him in antiquity. It is Hesiodic in style and has always formed part of the Hesiodic corpus. It makes up the third section of this book. The influence of Homer’s poems on Greek and later culture is inestima- ble, but Homer never tells us who he is; he stands behind his poems, invisi- ble, all-knowing. His probable contemporary Hesiod, by contrast, is the first self-conscious author in Western literature. Hesiod tells us something about himself in his poetry. His name seems to mean “he who takes pleasure in a journey” (for what it is worth) but in the Works and Days he may play with the meaning of “he who sends forth song.” As with all names—for example, Homer, meaning “hostage,” or Herodotus, meaning “a warrior’s gift”—the name of a poet may have nothing to do with his actual career. -

On Program and Abstracts

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY & MASARYK UNIVERSITY, BRNO, CZECH REPUBLIC TENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY TIME AND MYTH: THE TEMPORAL AND THE ETERNAL PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS May 26-28, 2016 Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic Conference Venue: Filozofická Fakulta Masarykovy University Arne Nováka 1, 60200 Brno PROGRAM THURSDAY, MAY 26 08:30 – 09:00 PARTICIPANTS REGISTRATION 09:00 – 09:30 OPENING ADDRESSES VÁCLAV BLAŽEK Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic MICHAEL WITZEL Harvard University, USA; IACM THURSDAY MORNING SESSION: MYTHOLOGY OF TIME AND CALENDAR CHAIR: VÁCLAV BLAŽEK 09:30 –10:00 YURI BEREZKIN Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography & European University, St. Petersburg, Russia OLD WOMAN OF THE WINTER AND OTHER STORIES: NEOLITHIC SURVIVALS? 10:00 – 10:30 WIM VAN BINSBERGEN African Studies Centre, Leiden, the Netherlands 'FORTUNATELY HE HAD STEPPED ASIDE JUST IN TIME' 10:30 – 11:00 LOUISE MILNE University of Edinburgh, UK THE TIME OF THE DREAM IN MYTHIC THOUGHT AND CULTURE 11:00 – 11:30 Coffee Break 11:30 – 12:00 GÖSTA GABRIEL Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany THE RHYTHM OF HISTORY – APPROACHING THE TEMPORAL CONCEPT OF THE MYTHO-HISTORIOGRAPHIC SUMERIAN KING LIST 2 12:00 – 12:30 VLADIMIR V. EMELIANOV St. Petersburg State University, Russia CULTIC CALENDAR AND PSYCHOLOGY OF TIME: ELEMENTS OF COMMON SEMANTICS IN EXPLANATORY AND ASTROLOGICAL TEXTS OF ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA 12:30 – 13:00 ATTILA MÁTÉFFY Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey & Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, -

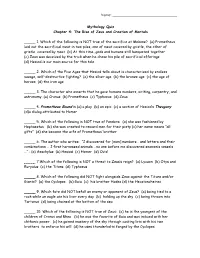

Mythology Quiz Chapter 4: the Rise of Zeus and Creation of Mortals

Name: ____________________________________ Mythology Quiz Chapter 4: The Rise of Zeus and Creation of Mortals _____ 1. Which of the following is NOT true of the sacrifice at Mekone? (a) Prometheus laid out the sacrificial meat in two piles, one of meat covered by gristle, the other of gristle covered by meat (b) At this time, gods and humans still banqueted together (c) Zeus was deceived by the trick when he chose his pile of sacrificial offerings (d) Hesiod is our main source for this tale _____ 2. Which of the Five Ages that Hesiod tells about is characterized by endless savage, self-destructive fighting? (a) the silver age (b) the bronze age (c) the age of heroes (d) the iron age _____ 3. The character who asserts that he gave humans numbers, writing, carpentry, and astronomy: (a) Cronus (b) Prometheus (c) Typhoeus (d) Zeus _____ 4. Prometheus Bound is (a) a play (b) an epic (c) a section of Hesiod’s Theogony (d)a dialog attributed to Homer _____ 5. Which of the following is NOT true of Pandora: (a) she was fashioned by Hephaestus (b) she was created to reward men for their piety (c) her name means “all gifts” (d) she became the wife of Prometheus’ brother _____ 6. The author who writes: “I discovered for [men] numbers… and letters and their combinations … I first harnessed animals …no one before me discovered seamen’s vessels …” : (a) Aeschylus (b) Hesiod (c) Homer (d) Ovid _____ 7.Which of the following is NOT a threat to Zeus’s reign? (a) Lycaon (b) Otys and Euryalus (c) the Titans (d) Typhoeus _____ 8. -

Shaushka, the Traveling Goddess Graciela GESTOSO SINGER

Shaushka, the Traveling Goddess Graciela GESTOSO SINGER Traveling gods and goddesses between courts was a well-known motif in the ancient Near East. Statues of gods and goddesses served as symbols of life, fertility, healing, prosperity, change, alliances and sometimes represented the “geographical” integration or the “ideological” legitimization of a territory. The Amarna Letters reveal the jour- ney of the goddess Shaushka to the Egyptian court of Amenhotep III. Akkadian, Hurrian, Hittite, and Ugaritic texts reveal the role played by this goddess in local pantheons, as well as in various foreign courts during the second millennium BCE. She was known as the goddess of war, fertility and healing and statues of the goddess were used in rituals performed before military actions, to heal diseases, to bless marriage alliances and assist births. This pa- per analyses the role of this traveling goddess in the Egyptian court of Amenhotep III. El viaje de estatuas de dioses y diosas entre cortes de grandes reyes fue un recurso conocido en el Cercano Oriente antiguo. En la Antigüedad, las estatuas de ciertos dioses y diosas fueron símbolos de vida, fertilidad, curación, prosperidad, cambio, alianzas y, en algunos casos, representaron la integración “geográfica” o la legiti- mación “ideológica” de un territorio. Las Cartas de El Amarna revelan el viaje de la estatua de la diosa Shaushka hacia la corte egipcia durante el reinado de Amenhotep III. Textos acadios, hurritas, hititas y ugaríticos indican el rol cumplido por esta diosa en panteones locales, así como en diversas cortes extranjeras durante el II milenio a.e. Fue reconocida como la diosa de la guerra, fertilidad y curación. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too. -

Nudity and Music in Anatolian Mythological Seduction Scenes and Iconographic Imagery

Ora Brison Nudity and Music in Anatolian Mythological Seduction Scenes and Iconographic Imagery This essay focuses on the role of Anatolian music in erotic and sexual contexts — especially of its function in mythological seduction scenes. In these scenes, music is employed as a means of enhancing erotic seduction. A number of cultic, sexual iconographic representations associated with musical instruments and performers of music will also be discussed. Historical Background Most of the data on the music culture of the Anatolian civilizations comes from the Old Hittite and Hittite Imperial periods, dating from 1750 to 1200 bce, though some data comes from the Neo-Hittite period, namely 1200 to 800 bce.1 The textual sources relate mainly to religious state festivals, ceremonies and rituals. It is likely that Hittite music culture reflected the musical traditions of the native Anatolian cultures — the Hattians2 — as well as the influences of other migrating ethnic groups, such as the Hurrians3 or the Luwians,4 who settled in Anatolia. Hittite music culture also shows the musical influence of and fusion with the neighboring major civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt and the Aegean (Schuol 2004: 260). Our knowledge of Anatolian music, musical instruments, musicians, singers and performers is based on extensive archaeological evidence, textual and visual, as well as on recovered pieces of musical artifacts. Much of the data has been collected from the corpus of religious texts and cultic iconographic representations. Nevertheless, we can assume that music, song and dance played a significant role not only in reli- gious practices, but also in many aspects of daily life (de Martino 1995: 2661). -

John David Hawkins

STUDIA ASIANA – 9 – STUDIA ASIANA Collana fondata da Alfonso Archi, Onofrio Carruba e Franca Pecchioli Daddi Comitato Scientifico Alfonso Archi, Fondazione OrMe – Oriente Mediterraneo Amalia Catagnoti, Università degli Studi di Firenze Anacleto D’Agostino, Università di Pisa Rita Francia, Sapienza – Università di Roma Gianni Marchesi, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna Stefania Mazzoni, Università degli Studi di Firenze Valentina Orsi, Università degli Studi di Firenze Marina Pucci, Università degli Studi di Firenze Elena Rova, Università Ca’ Foscari – Venezia Giulia Torri, Università degli Studi di Firenze Sacred Landscapes of Hittites and Luwians Proceedings of the International Conference in Honour of Franca Pecchioli Daddi Florence, February 6th-8th 2014 Edited by Anacleto D’Agostino, Valentina Orsi, Giulia Torri firenze university press 2015 Sacred Landscapes of Hittites and Luwians : proceedings of the International Conference in Honour of Franca Pecchioli Daddi : Florence, February 6th-8th 2014 / edited by Anacleto D'Agostino, Valentina Orsi, Giulia Torri. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2015. (Studia Asiana ; 9) http://digital.casalini.it/9788866559047 ISBN 978-88-6655-903-0 (print) ISBN 978-88-6655-904-7 (online) Graphic design: Alberto Pizarro Fernández, Pagina Maestra Front cover photo: Drawing of the rock reliefs at Yazılıkaya (Charles Texier, Description de l'Asie Mineure faite par ordre du Governement français de 1833 à 1837. Typ. de Firmin Didot frères, Paris 1839, planche 72). The volume was published with the contribution of Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze. Peer Review Process All publications are submitted to an external refereeing process under the responsibility of the FUP Editorial Board and the Scientific Committees of the individual series. -

Durham Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Durham Research Online Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 26 July 2016 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Haubold, J. (2017) 'Conict, consensus and closure in Hesiod's Theogony and Enma eli§s.',in Conict and consensus in Early Greek hexameter poetry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 17-38. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.cambridge.org/gb/academic/subjects/classical-studies/classical-literature/conict-and-consensus- early-greek-hexameter-poetry?format=HB Publisher's copyright statement: This material has been published in Conict and consensus in Early Greek hexameter poetry. / Edited by Paola Bassino, Lilah Grace Canevaro Barbara Graziosi. This version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. c Cambridge University Press 2017 Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 http://dro.dur.ac.uk 1 Conflict, consensus and closure in Hesiod’s Theogony and Enūma eliš Johannes Haubold Hesiod’s Theogony and the Babylonian Enūma eliš both move from chaos to order, divine conflict to consensus. -

Western and Japanese Mythology in Fullmetal Alchemist Brotherhood

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Larbi Ben M’hidi University-Oum El Bouaghi Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Western and Japanese Mythology in Fullmetal Alchemist Brotherhood A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Anglo-American Studies By: CHERAIFIA Djihed Supervisor: Miss HADDAD Mordjana Board of Examiners Examiner: Miss ACHIRI Samya JUNE 2016 i Dedication To my loved ones, you should always know that you are loved and that you have made this heart happy and innocent again. To those close to my heart, every time you smile, you melt away my fears and fill my heart with joy. To those who feel lonely and abandoned by this world because of their “childish” interests, without these interests this work would remain just a random thought in a closed mind. To those who battle life each day and feel they are growing weak and losing the battles, you might be losing few battles but you are winning the war. To the younglings who are pressured to think they are growing too old to fulfill their dreams, you can do it, dreams know no age. To whoever taught me a word, a skill, or an attitude, without all of you I wouldn’t be the person I am today (thank you). To those who held my hand when I was down and supported me when my feet were bruised, I shall support you and be there for you for the rest of my life.