Prostitution, Pee-Ing, Percussion, and Possibilities: Contemporary Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psyphil Celebrity Blog Covering All Uncovered Things..!! Vijay Tamil Movies List New Films List Latest Tamil Movie List Filmography

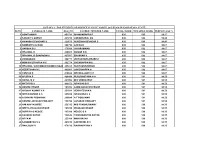

Psyphil Celebrity Blog covering all uncovered things..!! Vijay Tamil Movies list new films list latest Tamil movie list filmography Name: Vijay Date of Birth: June 22, 1974 Height: 5’7″ First movie: Naalaya Theerpu, 1992 Vijay all Tamil Movies list Movie Y Movie Name Movie Director Movies Cast e ar Naalaya 1992 S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Sridevi, Keerthana Theerpu Vijay, Vijaykanth, 1993 Sendhoorapandi S.A.Chandrasekar Manorama, Yuvarani Vijay, Swathi, Sivakumar, 1994 Deva S. A. Chandrasekhar Manivannan, Manorama Vijay, Vijayakumar, - Rasigan S.A.Chandrasekhar Sanghavi Rajavin 1995 Janaki Soundar Vijay, Ajith, Indraja Parvaiyile - Vishnu S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Sanghavi - Chandralekha Nambirajan Vijay, Vanitha Vijaykumar Coimbatore 1996 C.Ranganathan Vijay, Sanghavi Maaple Poove - Vikraman Vijay, Sangeetha Unakkaga - Vasantha Vaasal M.R Vijay, Swathi Maanbumigu - S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Keerthana Maanavan - Selva A. Venkatesan Vijay, Swathi Kaalamellam Vijay, Dimple, R. 1997 R. Sundarrajan Kaathiruppen Sundarrajan Vijay, Raghuvaran, - Love Today Balasekaran Suvalakshmi, Manthra Joseph Vijay, Sivaji - Once More S. A. Chandrasekhar Ganesan,Simran Bagga, Manivannan Vijay, Simran, Surya, Kausalya, - Nerrukku Ner Vasanth Raghuvaran, Vivek, Prakash Raj Kadhalukku Vijay, Shalini, Sivakumar, - Fazil Mariyadhai Manivannan, Dhamu Ninaithen Vijay, Devayani, Rambha, 1998 K.Selva Bharathy Vandhai Manivannan, Charlie - Priyamudan - Vijay, Kausalya - Nilaave Vaa A.Venkatesan Vijay, Suvalakshmi Thulladha Vijay 1999 Manamum Ezhil Simran Thullum Endrendrum - Manoj Bhatnagar Vijay, Rambha Kadhal - Nenjinile S.A.Chandrasekaran Vijay, Ishaa Koppikar Vijay, Rambha, Monicka, - Minsara Kanna K.S. Ravikumar Khushboo Vijay, Dhamu, Charlie, Kannukkul 2000 Fazil Raghuvaran, Shalini, Nilavu Srividhya Vijay, Jyothika, Nizhalgal - Khushi SJ Suryah Ravi, Vivek - Priyamaanavale K.Selvabharathy Vijay, Simran Vijay, Devayani, Surya, 2001 Friends Siddique Abhinyashree, Ramesh Khanna Vijay, Bhumika Chawla, - Badri P.A. -

Sounds of Madras USB Booklet

A R RAHMAN 16 Parandhu Sella Vaa 1 Saarattu Vandiyila O Kadhal Kanmani Kaatru Veliyidai 17 Manamaganin Sathiyam 2 Mental Manadhil Kochadaiiyaan O Kadhal Kanmani 18 Nallai Allai 3 Mersalaayitten Kaatru Veliyidai I 19 Innum Konjam Naeram 4 Sandi Kuthirai Maryan Kaaviyathalaivan 20 Moongil Thottam 5 Sonapareeya Kadal Maryan 21 Omana Penne 6 Elay Keechan Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa Kadal 22 Marudaani 7 Azhagiye Sakkarakatti Kaatru Veliyidai 23 Sonnalum 8 Ladio Kaadhal Virus I 24 Ae Maanpuru Mangaiyae 9 Kadal Raasa Naan Guru (Tamil) Maryan 25 Adiye 10 Kedakkari Kadal Raavanan 26 Naane Varugiraen 11 Anbil Avan O Kadhal Kanmani Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa 27 Ye Ye Enna Aachu 12 Chinnamma Chilakamma Kaadhal Virus Sakkarakatti 28 Kannukkul Kannai 13 Nanare Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa Guru (Tamil) 29 Veera 14 Aye Sinamika Raavanan O Kadhal Kanmani 30 Hosanna 15 Yaarumilla Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa Kaaviyathalaivan 31 Aaruyirae 45 Maanja Guru (Tamil) Maan Karate 32 Theera Ulaa 46 Hey O Kadhal Kanmani Vanakkam Chennai 33 Idhayam 47 Sirikkadhey Kochadaiiyaan Remo 34 Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa 48 Nee Paartha Vizhigal - The Touch of Love Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa 3 35 Usure pogudhey 49 Ailasa Ailasa Raavanan Vanakkam Chennai 36 Paarkaadhey Oru Madhiri 50 Boomi Enna Suthudhe Ambikapathy Ethir Neechal 37 Nenjae Yezhu 51 Oh Penne Maryan Vanakkam Chennai 52 Enakenna Yaarum Illaye ANIRUDH R Aakko 38 Oh Oh - The First Love of Tamizh 53 Tak Bak - The Tak Bak of Tamizh Thangamagan Thangamagan 39 Remo Nee Kadhalan 54 Osaka Osaka Remo Vanakkam Chennai 40 Don’u Don’u Don’u -

Commencement Program: 2017 Governors State University

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Commencement Documents and Videos Commencement 5-20-2017 Commencement Program: 2017 Governors State University Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/commencements Recommended Citation Governors State University, "Commencement Program: 2017" (2017). Commencement Documents and Videos. 147. http://opus.govst.edu/commencements/147 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Commencement at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commencement Documents and Videos by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commencement Exercises of the Forty-Sixth Academic Year SATURDAY, MAY 20, 2017 • 10 A.M. & 5 P.M. GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY From its inception in 1969, innovation and putting students first have been the hallmarks of GSU’s success. In 2017, that tradition continues. The university has expanded its reach and has solidified its commitment to inspiring hope, realizing dreams, and strengthening community for generations to come. Our work is informed by the following principles: GSU’s strategic planning and financial decisions always put students first. We know that nothing in higher education is more powerful than an uncompromising commitment to student success. GSU students deserve a high quality education, with a strong foundation in critical thinking, civic engagement, and communications. Credentials without quality are empty. GSU is an “island of excellence,” according to Dr. Martha J. Kanter, former Under Secretary of the United States Department of Education. With bold new initiatives and innovative undergraduate and graduate degree programs, GSU excels at providing the quality education that is essential for success in today’s global society. -

MONSOON WEDDING a NEW MUSICAL by MIRA NAIR a Leeds Playhouse Production in Association with the Roundhouse

PRESS RELEASE – Thursday 5th December 2019 IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE MonsoonWeddingmusical.co.uk / @Monsoonmusical MONSOON WEDDING A NEW MUSICAL BY MIRA NAIR A Leeds Playhouse production in association with the Roundhouse • A NEW MUSICAL THEATRE ADAPTATION OF THE HIT FILM MONSOON WEDDING WILL PLAY AT LEEDS PLAYHOUSE AND LONDON’S ROUNDHOUSE IN SUMMER 2020 • DIRECTED BY THE FILM’S DIRECTOR MIRA NAIR, THE NEW MUSICAL FEATURES A BOOK BY SABRINA DHAWAN AND ARPITA MUKHERJEE AND LYRICS BY MASI ASARE AND SUSAN BIRKENHEAD WITH MUSIC BY VISHAL BHARDWAJ Nearly 20 years after the multi award-winning Monsoon Wedding broke all moulds by becoming one of the most successful international films of all time and introducing a worldwide audience to Indian culture through the joy of the rom-com, the beautiful story of finding love against the odds returns as a brand-new musical. Co-Directors Mira Nair (Salaam Bombay, Mississippi Masala and forthcoming BBC adaptation A Suitable Boy) and Stephen Whitson (West Side Story Edinburgh International Festival and BBC Prom and UK associate for Hamilton) have worked with book writers Arpita Mukherjee (Artistic Director of Hypokrit Theatre, 2018-2020 WP Theater Directors Lab member, 2018 Eugene O’Neill National Directing Fellow) and Sabrina Dhawan (original Monsoon Wedding screenplay, written for 20th Century Fox, HBO, Disney Animations, Fox Star and Killer Films), award-winning composer Vishal Bhardwaj (over 40 Bollywood films, 6 National Film Awarads, winner of People’s Choice Award at Rome Film Festival for Hamlet) and lyricists Masi Asare (Music and Lyrics for Sympathy Jones, music and lyrics for Family Resemblance Theatre Royal Stratford East) and Susan Birkenhead and orchestrator Jamshied Sharfiri (winner of the Tony© for Best Orchestration for The Band’s Visit) to bring the film to life on the stage. -

Bend It Like Beckham

Bend It Like Beckham Dir. Gurinder Chadha, UK/Germany 2002, Certificate 12A Introduction Bend It Like Beckham was one of the surprise hits of 2002, making over £11,000,000 at the UK Box Office and hitting a chord with a range of audiences at cinemas. A vibrant and colourful British comedy about a young girl from a Sikh family who desperately wants to play football against the wishes of her traditional parents, the film can be seen to follow the path of other recent British-Asian films such as Bhaji on the Beach, Anita and Me and East Is East in its examination of culture clashes and family traditions. Bend It Like Beckham takes these themes and adds extra ingredients to the dish – football, Shakespearean confusions over identity and sexuality, in-jokes about both British pop culture and the Sikh way of life, and a music soundtrack mixing a range of East/West sounds and musical styles. It is also useful to look at Bend It Like Beckham within a wider context of the British Asian experience in popular culture and media, such as portrayal of Asian culture on television including Ali G, Goodness Gracious Me, families in soaps such as Coronation Street and EastEnders – even the new Walkers Crisps advert has Gary Lineker in a mini-Bollywood musical - and the Asian language, music and fashion that has now flowed into the mainstream. © Film Education 2003 1 Film Synopsis Jesminder (known as Jess) is a Sikh teenager living in Hounslow, who loves to play football. Her parents disapprove, wanting her to settle down, get a job as a lawyer and marry a nice Indian boy. -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION -

Mno Regn No Name Father's NAME NEET Rollno NEET Marks NEET

Provisional Merit List of Candidates who have applied for admission to NEET UG-2020 under Backward Class Category (code-13) Mno Regn No Name Father's NAME NEET Rollno NEET NEET Category Marks Rank Applied 1 903099 VANI KARGWAL SURINDER 3802005389 682 511 11,13,11, KUMAR 11 2 903112 ASHISHPREET DAVINDER 3803004562 677 754 13,11 SINGH SINGH 3 902178 KULJEET SINGH DALWINDER 3802002454 665 1685 13,11 GAHLA SINGH GAHLA 4 901770 HARSHIT VERMA NARINDER 3802002498 658 2544 13,11 VERMA 5 902541 ANNIRUDH JASHPAL 3801001604 649 4131 13 6 900345 SHEMANE DALJIT SINGH 3802005423 646 4548 13,11 7 902624 RAVNEET KAUR JAGJIT SINGH 3803003680 627 9279 13,11 8 901844 ABHINAV JOGINDER SINGH 3804001100 627 9418 13,14,11, CHAUDHARY 11 9 903640 SONAM KUMARI SUSHIL KUMAR 3905104208 620 11550 29,13,11, YADAV 11 10 901438 RIYA ROOP LAL 3801005187 614 13924 13,29,11, 11 11 903370 KHUSHPREET MANDEEP SINGH 1601207049 614 13953 13,11 KAUR DARDI DARDI 12 901498 AMARDEEP HARINDER PAL 3801003053 610 15310 13 SINGH SINGH 13 900296 MUSKAAN RAVINDER 3801003327 610 15360 13 KUMAR 14 900975 NISCHEJIT SINGH MEHAR SINGH 3803004570 610 15640 13 15 903096 PAYAL PARMOD 1601114188 609 15789 13 PRAJAPATI KUMAR 16 901771 PANKHURI KASTURI LAL 3801001594 606 17051 13,13,11, SALOTRA 11 17 901124 JASKARAN SINGH AVTAR SINGH 3803003480 606 17177 13 18 904215 ANSHU RULDU 3805002726 605 17774 13 19 901444 HARLEEN KAUR MANINDER 3802004310 602 18748 13,14,11, SINGH 11 20 901223 ABDUL DANISH ABDUL SATTAR 3805001110 601 19641 13,11 21 903420 SANJOG KUMAR NIRMAL KUMAR 3804001078 599 20286 13 KUSHWAHA -

2020 Projectcsgirls Competition for Middle School Girls Semifinalists Student Name(S) (Grade) School State Coach/Mentor Madhusha

2020 ProjectCSGIRLS Competition for Middle School Girls Semifinalists Student Name(s) (Grade) School State Coach/Mentor Madhushalini Balaji (8th) Liberty Middle School Alabama Balaji Purushothaman Rachel Kan (8th) BASIS Chandler Arizona Siva Rajagopalan, Leela Raj-Sankar (8th) Bogle Junior High School Arizona Leela Raj-Sankar Smriti Rangarajan (8th) Kennedy Middle School California Eduardo Basurto Reshma Kosaraju (8th) The Harker School California Hari Kosaraju Anika Pallapothu (7th) The Harker Middle School California Debajyothi Nath Sanaa Bhorkar (7th), Kennedy Middle School, Miller Aradhana Sekar (7th), Avani California Anand Rajasekar Middle School Viswanathan (7th) Jagriti Jha (7th) Fruitvale Jr. High School California Saanvi Bhargava (7th) The Harker Middle School California Rishi Bhargava Manvika Gopalasetty (7th), Kennedy Middle School California Anand Rajasekar Trisha Subramanyam (7th) Anagha Ashtewale (7th) Oak Valley Middle School California Maryann Cowley Varsha Iyengar (7th), Meera Kennedy Middle School California Anand Rajashekar Bhaskar (7th) Amanda Deng (8th), Claire William Hopkins Junior High School California Miao (8th) Anisha Shukla (8th), Felicia Chaboya Middle School California Chiu (8th) Caitlin Stoiber (7th) Redwood Middle School California Aanvi Zade (7th) Oak Valley Middle School California Vrinda Zade Suhana Shrivastava (8th) William Hopkins Junior High School California Anoushka Shrivastava Allison Wu, Sophia Razzaq, Nikita Jadhav (8th) Double Peak School California Ameya Jadhav Quinn Burns (8th) Peak to Peak -

It's a Wrap: Columbia Film Festival Winners Announced

4 C olumbia U niversity RECORD June 11, 2004 It’s a Wrap: Columbia Film Festival Winners Announced ilm Division students received $110,000 in Fawards at the 17th Annual Columbia University Film Festi- val for works that ranged from a woman’s daily struggle to care for her child and her mother, who has Alzheimer’s disease (Extreme Mom) to a documen- tary in which members of a Harlem family recount the chal- lenges they have faced since Gordon Parks photographed them in 1968 for Life magazine (Family Portrait). The student-run festival, pre- sented by the Film Division of the School of the Arts, included original short films and screen- play readings. It took place from May 1-7 in New York City and then headed west to Los Angeles June 2-3. Student filmmaker Joyce Draganosky, whose film Extreme Mom swept many of the festi- val’s awards May 7, based her work on growing up in a house- hold where her mother raised her while also caring for her elderly grandmother. “It’s a movie about the circle of life, and a woman stuck in the middle of trying to care for both ends of that spectrum,” “Junebug and Hurricane,” written and directed by James Ponsoldt, garnered several awards and will screen at the Atlanta Film Festival. Draganosky said. “The situation is such that the child is learning activities and the grandmother is tary Family Portrait, which pose of her documentary: “Right After the readings, SOA alum- Portrait, directed by Patricia losing activities.” received the New Line Cinema now, there are a million black na Sabrina Dhawan, ’02, Riggen; and God Is Good, Extreme Mom was named a Award for Outstanding Achieve- kids that live in extreme poverty received the Andrew Sarris directed by Caryn Waechter. -

SPRING 2019 Greetings from the President

COMMENCEMENT COMMENCEMENT APP Download the UF Commencement APP for latest information. GATORWAY is the offi cial events mobile app of the University of Florida and is free to download on Android or IOS. Have all your necessary UF graduation weekend information handy on your mobile device. https://guidebook.com/app/gatorway/ SOCIAL MEDIA Whether you are a #UFGrad or you are here to celebrate a #UFGrad, we invite you to join the commencement conversation on social media. Select tweets will be featured on the video boards prior to and after the ceremony. COMMENCEMENT PROGRAM Additional copies of this commencement program are available while supplies last at the UF Bookstore for a $1 donation to the Machen Florida Opportunity Scholars program, which helps fund a UF education for low-income students who are fi rst in their family to attend college. The commencement program can be ordered online with an additional charge for shipping and handling. THIS IS NOT AN OFFICIAL GRADUATION LIST While every eff ort is made to ensure accuracy in this commencement program, printing deadlines may result in omission of some names and use of names of persons not completing graduation requirements as intended. This printed program, therefore, should not be used to determine a student’s academic or degree status. The university’s offi cial registry for conferral of degrees is the student’s permanent academic record as refl ected on the student’s transcript, maintained by the Offi ce of the University Registrar. Commencement SPRING 2019 Greetings from the President n behalf of the University of Florida and our administration, faculty and staff, I would like to extend my heartfelt congratulations to you, the OClass of 2019, and to your family and friends. -

Slno Candidate Name Reg No Father / Mother Name Total Mark Obtained Mark Percentage % 1 Gowthami P 401511 Shankarappa P 600

LIST OF 1% TOP STUDENTS OF SCIENCE IN II PUC MARCH 2015 EXAM IN KARNATAKA STATE SLNO CANDIDATE NAME REG_NO FATHER / MOTHER NAME TOTAL MARK OBTAINED MARK PERCENTAGE % 1 GOWTHAMI P 401511 SHANKARAPPA P 600 595 99.17 2 SANJAY V GORUR 427216 VARADHARAJ GV 600 594 99.00 3 AVINASH DEVADHAR S 222676 SURESHA DEVADAR C 600 593 98.83 4 NAMRATHA G NAIK 204796 G B NAIK 600 592 98.67 5 HARSHA B J 173398 JAYARAMAIAH 600 592 98.67 6 PRAJWAL K 426081 KUMAR N K 600 592 98.67 7 PRAJWAL B BHARADWAJ 427037 BHASKAR V 600 592 98.67 8 VANDANA M 254771 VIDYADHARA PRABHU 600 592 98.67 9 MONISH UTHAPPA M C 252774 CHENGAPPA M U 600 592 98.67 10 PRAJWAL SUKHAMUNISWAMI LINGAD 253223 SUKHAMUNISWAMI 600 592 98.67 11 KEERTHANA H L 962063 LOKESHAPPA H 600 592 98.67 12 YASHAS D 478628 DEVARAJAIAH V C 600 592 98.67 13 APURVA P 426494 PURUSHOTAMA N A 600 591 98.50 14 RAHUL M V 427092 M N VENKATESH 600 591 98.50 15 MYTHRI B S 962152 SRINIVAS B V 600 591 98.50 16 RASHMI HEGDE 101012 LAXMINARAYAN HEGDE 600 591 98.50 17 AKSHAY KUMAR V N 251031 VENKATESHA N 600 591 98.50 18 NITHIN KUMAR K S 253016 SRINIVASA K S 600 591 98.50 19 A SHIVANI POOVAIAH 260684 A T POOVAIAH 600 591 98.50 20 RASHMI JAYAKAR POOJARY 190784 JAYAKAR POOJARY 600 591 98.50 21 N M NAVYASHREE 252795 M B PRABHUSWAMY 600 590 98.33 22 NEETA PRAKASH HEGDE 101836 PRAKASH HEGDE 600 590 98.33 23 SUPRIYA G HEGDE 195919 HEGDE G S 600 590 98.33 24 KAUSHIK NAYAK 192642 YASHAWANTHA NAYAK 600 590 98.33 25 ARYA M 255164 MANI NAYAK 600 590 98.33 26 SANGEETHA V S 461810 SAKTHIVEL E V 600 590 98.33 27 PHALGUNI R 478130 RAVINARAYAN -

John Adams Middle School HR2MP2 2019-20 Marking Period 2

John Adams Middle School HR2MP2 2019-20 Marking Period 2 Grade 6 Ajoy, Johan Allidina, Serena Amagowni, Dhruv Anand, Advika Appana, Narun Aravindan, Arjun Arji, Sriman Arya, Shaurya Ashok, Sahaanaa Bajaj, Mishti Banerjee, Durva Bansal, Divya Bapat, Veeren Barskiy, Steven Basavaraj, Eshaan Batchali, Sreya Behera, Pranava Berrios, Jayden Bhalerao, Pranav Bhandar, Eshaan Bhatt, Rohan Bhoyar, Priyanshu Biezewski-Carter, Calissa Borkar, Ava Bose, Inesh Bothra, Neev Brett, Brielle Budhan, Sanya Cadet, Rayahna Calara, Elena Chakrabarty, Drisana Chaudhari, Omkar Chaudhuri, Ritam Chopra, Esmeet Cruz Paredes, Hector D'Souza, Ashlyn Das, Bihan Devarakonda, Shruthi Dichwlkar, Arusha Doshi, Aksh Farooqui, Daniyal John Adams Middle School HR2MP2 2019-20 Marking Period 2 Gamini, Gaayathri Gandhi, Guru Garcia, Cristian Gaur, Arya Ghedia, Dhwani Goel, Aarush Gopinath, Aditya Goswami, Eshani Grossman, Ethan Grossman, Nathaniel Gupta, Kavya Huzaifa, Mohammad Jain, Arnav Jain, Tarun Jasuja, Khushi Jawad, Maaz Joshi, Aashita Joshi, Ayush Joshi, Kavya Kalla, Rohit Kamalakkannan, Shrinithi Kamaluddin, Ayishah Kanchi, Manushree Kandagatla, Pradyun Kapoor, Soham Karthik, Gowtham Kazmi, Abd-Ar-Rahman Kochay, Hosna Koduri, Rishith Kohli, Keefer Krishna, Suhas Kudari, Sahaana Kulkarni, Sahil Kulkarni, Sonia Kumar, Avni Kumaraja, Gurubaran Lai, Evan Lee, Matthew Lo, Tyler Maddala, Maanas Malladi, Saketh Maloo, Nikul Mangukia, Yashwari John Adams Middle School HR2MP2 2019-20 Marking Period 2 Manolakis, Emanuel Manwani, Kritika Masood, Sarwary Mathur, Prisha Mehta,