Standard Lawyer Behavior? Professionalism As an Essential Standard for ABA Accreditation Nicola A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston College Law School Magazine Fall 1998 Boston College Law School

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Magazine 10-1-1998 Boston College Law School Magazine Fall 1998 Boston College Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclsm Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Boston College Law School, "Boston College Law School Magazine Fall 1998" (1998). Boston College Law School Magazine. Book 12. http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclsm/12 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. P UB LICATION NOTE BOSTON COLLEGE LAw SCHOOL INTERIM D EAN James S. Rogers DIRECroR OF INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT Deborah Blackmore Abrams EDITOR IN C HIEF Vicki Sanders CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Vijaya Andra Suzanne DeMers Michael Higgins Carla McDonald Kim Snow Abby Wolf Boston College Law School Magazine On the Cover: welcomes readers' comments. Yo u may comac[ us by phone at (6 17) 552-2873; by mail at Photographer Susan Biddle captures Boston Coll ege Law School, Barat House, 885 Centre Street, Newton. MA 02459- 11 63; Michael Deland in the autumn sunlight or bye-mail at [email protected]. at the FOR Memorial in Washington, DC. Copyright 1998, Boston Coll ege Law School. All publicatio n rights reserved. Opinions expressed in Boston College Law School Magazine do not necessar ily refl ecr the views of Boston College Law School or Boston College. -

Unai Members List August 2021

UNAI MEMBER LIST Updated 27 August 2021 COUNTRY NAME OF SCHOOL REGION Afghanistan Kateb University Asia and the Pacific Afghanistan Spinghar University Asia and the Pacific Albania Academy of Arts Europe and CIS Albania Epoka University Europe and CIS Albania Polytechnic University of Tirana Europe and CIS Algeria Centre Universitaire d'El Tarf Arab States Algeria Université 8 Mai 1945 Guelma Arab States Algeria Université Ferhat Abbas Arab States Algeria University of Mohamed Boudiaf M’Sila Arab States Antigua and Barbuda American University of Antigua College of Medicine Americas Argentina Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Facultad Regional Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Universidad Abierta Interamericana Americas Argentina Universidad Argentina de la Empresa Americas Argentina Universidad Católica de Salta Americas Argentina Universidad de Congreso Americas Argentina Universidad de La Punta Americas Argentina Universidad del CEMA Americas Argentina Universidad del Salvador Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Avellaneda Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cordoba Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de la Pampa Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Rosario Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de -

STS Departments, Programs, and Centers Worldwide

STS Departments, Programs, and Centers Worldwide This is an admittedly incomplete list of STS departments, programs, and centers worldwide. If you know of additional academic units that belong on this list, please send the information to Trina Garrison at [email protected]. This document was last updated in April 2015. Other lists are available at http://www.stswiki.org/index.php?title=Worldwide_directory_of_STS_programs http://stsnext20.org/stsworld/sts-programs/ http://hssonline.org/resources/graduate-programs-in-history-of-science-and-related-studies/ Austria • University of Vienna, Department of Social Studies of Science http://sciencestudies.univie.ac.at/en/teaching/master-sts/ Based on high-quality research, our aim is to foster critical reflexive debate concerning the developments of science, technology and society with scientists and students from all disciplines, but also with wider publics. Our research is mainly organized in third party financed projects, often based on interdisciplinary teamwork and aims at comparative analysis. Beyond this we offer our expertise and know-how in particular to practitioners working at the crossroad of science, technology and society. • Institute for Advanced Studies on Science, Technology and Society (IAS-STS) http://www.ifz.tugraz.at/ias/IAS-STS/The-Institute IAS-STS is, broadly speaking, an Institute for the enhancement of Science and Technology Studies. The IAS-STS was found to give around a dozen international researchers each year - for up to nine months - the opportunity to explore the issues published in our annually changing fellowship programme. Within the frame of this fellowship programme the IAS-STS promotes the interdisciplinary investigation of the links and interaction between science, technology and society as well as research on the development and implementation of socially and environmentally sound, sustainable technologies. -

Bridging the Gap: Legal Education and Lawyer Competency E

BYU Law Review Volume 1977 | Issue 4 Article 6 11-1-1977 Bridging the Gap: Legal Education and Lawyer Competency E. Gordon Gee Donald W. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation E. Gordon Gee and Donald W. Jackson, Bridging the Gap: Legal Education and Lawyer Competency, 1977 BYU L. Rev. 695 (1977). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol1977/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Bridging the Gap: Legal Education and Lawyer Competencyt E. Gordon Gee* and Donald W. Jackson** Summary of Contents Introduction A. Origins and Purposes B. Methodology C. Outline and Cautionary Notes Contemporary Issues in the Training of the American Lawyer A. Alternative Priorities in Legal Education B. Alternative Structures in Legal Education C. Alternative Methods in Legal Education D. Evaluative Stages and Techniques I E. Professional Responsibility and Ethics F. Financing of Legal Education G. Conclusion American Legal Education and the Bar: Hand in Hand or Fist in Glove? ~ntroduction 719 1. The American lawyer: A new breed 719 2. A recurrent theme: Practical experience versus academic education 721 Legal Education Prior to 1870: Challenges to the Apprenticeship System 722 1. Early attempts at academic training in the law 725 2. -

Curriculum Vitae and Publications List

CURRICULUM VITAE AND PUBLICATIONS LIST Family (sur) name WOUTERS First names Jan Maria Florent Date and place of birth 14 July 1964, Deurne, Belgium Address and Contact Data Leuven Centre for Global Governance Studies Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (K.U.Leuven) Blijde Inkomststraat 5, 3000 Leuven, Belgium T. ++32-16-32.87.33, F. ++32-16-32.87.26 Mobile phone ++32-478.32.11.77 e-mail [email protected] Educational Qualifications PhD in Law, K.U.Leuven (1996) Visiting Researcher, Harvard Law School (1990-91) Master of Laws, Yale University (1990) Lic. Juris, Antwerp University (1987) Bachelor of Philosophy, Antwerp University (1984) Positions Currently Held Professor of International Law and the Law of International Organizations, K.U.Leuven (courses: public international law, law of international organizations, law of the World Trade Organization, armed conflicts and the law) Director of the Leuven Centre for Global Governance Studies and Institute for International Law, K.U.Leuven President, United Nations Assocation Flanders-Belgium President, Strategic Advisory Council International Flanders Of Counsel, Linklaters, Brussels Former Positions 1997-2003 Professor of European Banking and Securities Law, Maastricht University 1997-1998 Senior Lecturer on European, Economic and Financial Law, Antwerp University 1993-1998 Lecturer and Senior Lecturer in European and International Law, Maastricht University 1991-1994 Law Clerk (référendaire), European Court of Justice, Luxembourg 1989 Legal Adviser to the Belgian Minister -

Lawyers and Notaries in the Rome Consular District

Lawyers and Notaries in the Rome Consular District (The Rome district contains the regions of Lazio, Abruzzo, Marche, Umbria and Sardinia) Disclaimer: The U.S. Embassy in Rome assumes no responsibility or liability for the professional ability, reputation or the quality of services provided by the persons or firms listed. Inclusion on this list is in no way an endorsement by the Department of State or the U.S. Embassy. Names are listed alphabetically within each region and the order in which they appear has no other significance. The information on the list regarding professional credentials, areas of expertise and language ability is provided directly by the lawyers. The U.S. Embassy is not in a position to vouch for such information. You may receive additional information about the individuals by contacting the local bar association or the local licensing authorities. REGION OF LAZIO BARBERA, Vittorio • Address: Via Firenze 32, 00184 Rome • Tel: 06-4898-9699; Cell: 339-140-2444; Fax: 06-4890-3535 • E-mail: [email protected] • Webpage: www.barberassociati.com • Born 1964; University of Rome; JD at Cornell Law School, NY; admitted to Bar: 1995. Adoptions, automobile accidents, banking/financial, child custody, civil damages, collections, commercial law, contracts, corporate law, criminal law, estates, foreign claims, foreign investments, government relations, insurance, labor relations, marketing agreements, marriage/divorce, mining/petroleum, narcotics, patents/trademarks/copyrights, taxes, theft/fraud/embezzlement. Language: English. BELTRAMO, Susanna • Address: Via Vittorio Veneto 84, 00187 Rome • Tel: 06-481-7747; Fax: 06-482-0281; Cell: 335-307-928 • Email: [email protected] • Born 1955; University of Rome; post graduate at University of Stanford, CA; admitted to Bar: 1985. -

Complete List of Participating Tuition Exchange Institutions

Complete List of Participating Tuition Exchange Institutions United Arab Emirates Massachusetts (continued) Ohio (continued) American University Sharjah - UAE Boston University - MA Mercy College of Northwest Ohio Clark University - MA - OH Greece Curry College - MA Mount St. Joseph University - American College of Greece - GR Dean College - MA OH Elms College - MA Mount Vernon Nazarene Canada Emerson College - MA University - OH King's University College at Western Emmanuel College - MA Muskingum University - OH University - CN Endicott College - MA Notre Dame College - OH Fisher College - MA Ohio Dominican University - OH Alabama Hampshire College - MA Ohio Northern University - OH Birmingham-Southern College - AL Hellenic College Holy Cross - MA Ohio Wesleyan University - OH Huntingdon College - AL Lasell College - MA Otterbein University - OH Judson College - AL Lesley University - MA Tiffin University - OH Samford University - AL Merrimack College - MA University of Dayton - OH Mount Holyoke College - MA University of Findlay - OH Alaska Mount Ida College -MA University of Mount Union - OH Alaska Pacific University - AK National Graduate School of Quality Ursuline College - OH Management - MA Walsh University - OH Arizona Newbury College - MA Wilmington College - OH Arizona Christian University - AZ Nichols College - MA Wittenberg University - OH Grand Canyon University - AZ Pine Manor College - MA Xavier University - OH Prescott College - AZ Regis College - MA Simmons College - MA Oklahoma Arkansas Smith College - MA Oklahoma City -

List of Members

The Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER) List of Members 31 May 2017 ASPHER Full Members 02 ASPHER Associate Members 07 Schools being part of the network structures belonging to ASPHER 08 ASPHER Secretariat UM Campus Brussels Av. de l’Armeé / Legerlaan 10 B1040 Brussels, Belgium Telephone: +32 2 735 0890 E-mail: [email protected] Page 02 This list covers i. ASPHER Full members (n = 107), ii. ASPHER Associate Members (n = 13), and iii. Schools being part of the network structures belonging to ASPHER (n = 42). ASPHER Full Members Nr COUNTRY SCHOOL UNIVERSITY 1 Albania Faculty of Public Health University of Medicine 2 Armenia School of Public Health American University of Armenia 3 Austria ULG – Public Health Medical University of Graz Department of Public Health and UMIT - The Health and 4 Austria Health Technology Assessment Life Sciences University 5 Austria Institute for Hygiene and Social Medicine Medical University of Innsbruck Department of International Health and MCI Management Center 6 Austria Social Management Innsbruck 7 Belgium Department of Public Health Sciences University of Liege 8 Bulgaria Faculty of Public Health Medical University of Pleven 9 Bulgaria Faculty of Public Health Medical University of Plovdiv 10 Bulgaria Faculty of Public Health Medical University of Sofia 11 Bulgaria Faculty of Public Health Medical University of Varna 12 Croatia Andrija Stampar School of Public Health University of Zagreb 13 Cyprus Public Health Program European University Cyprus Cyprus International Institute -

Books for You: a Booklist for Senior High Students

'DOCUMENT RESUME ED 130 270 CS 202 973 AUTHOR Donelson, Kenneth L., Ed.; And Others TITLE Books for You: A Booklist for Senior High Students. Sixth Edition. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, PUB DATE 76 NOTE 490p.; Compiled by the Committee on the Senior High School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English AVAILABLE gRomNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801 (Stock No. 03626, $2.95 non-member, $2.25 member) .EDRS PRICE MF-$1.00 HC-$26.11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; *Annotated Bibliographies; *Booklists; *Books; *High School Students; literature; Reading, Materials; Secondary Education; Teenagers ABSTRACT The books listed in this annotated bibliography have been selected to provide pleasurable reading for,high school students. Books are arranged alphabetically by author,under 43_main categories. Concluding the book are a directory of publishersand indexes of authors and titles. (JM) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makesevery effort * * to obtain'the best'copy available. Nevertheless, itemsof marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality. * * .of the:microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS isnot * responsible for the quality.of the original document. leproductions* * supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. * *********************************************************************** . U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE DF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN- ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE- SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF z EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

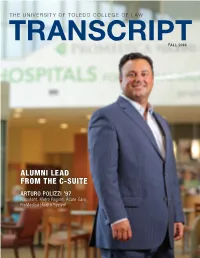

Alumni Lead from the C-Suite

THE UNIVERSITY OF TOLEDO COLLEGE OF LAW TRANSCRIPT FALL 2016 ALUMNI LEAD FROM THE C-SUITE ARTURO POLIZZI ’97 President, Metro Region, Acute Care ProMedica Health System Back by popular demand! Toledo Law branded apparel by Land’s End HTTPS://BUSINESS.LANDSEND.COM/STORE/TOLEDOLAW OCTOBER 10, 2016 When I joined the College of Law last year, I was excited to become part of such a great institution. I’m even more excited now than I was then. The faculty and staff here are truly outstanding, and I enjoy working with them every day. (You can read about a number of awards given to the faculty this year on page 33). The students are wonderful, and I’m energized by their enthusiasm. The alumni community has been incredibly supportive and welcoming. I’ve had an opportunity to meet many of you over the past year, and I look forward to meeting many more of you in the coming months. The new academic year got off to a great start as we welcomed our new, first-year class. As many of you know, enrollment has declined at the College of Law for the past several years, following national trends. Although law school enrollment was flat this year, we were able to get our trend line pointing up, increasing our JD enrollment by 12 percent. At the same time, we were able to increase the credentials of our incoming students. Our median undergraduate GPA increased to 3.39, the highest it has been for at least 10 years. Our median LSAT increased one point to 152, and our 25th percentile LSAT increased two points to 149. -

Law School Announcements 1967-1968 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected]

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound University of Chicago Law School Announcements Law School Publications 9-30-1967 Law School Announcements 1967-1968 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ lawschoolannouncements Recommended Citation Editors, Law School Announcements, "Law School Announcements 1967-1968" (1967). University of Chicago Law School Announcements. Book 92. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements/92 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Law School Announcements by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago The Law School Announcements 1967-1968 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LAW SCHOOL Inquiries should be addressed as follows: Requests for information, materials, and application forms for admission and finan cial aid: For the J.D. Program: DEAN OF STUDENTS The Law School The University of Chicago I II I East ooth Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 2406 For the Graduate Programs: ASSISTANT DEAN (GRADUATE STUDIES) The Law School The University of Chicago I I I I East ooth Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 2433 Housing for Single Students: OFFICE OF STUDENT HOUSING The University of Chicago 580 I Ellis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 3149 Housing for Married Students: OFFICE OF MARRIED STUDENT HOUSING The University of Chicago 824 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone 752-3644 Payment of Fees and Deposits: THE BURSAR The University of Chicago 5801 Ellis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 3146 The University of Chicago Founded by John D. -

Education Opportunities in Space Law: a Directory

A/AC.105/C.2/2018/CRP.11 16 April 2018 English only Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space Legal Subcommittee Fifty-seventh session Vienna, 9–20 April 2018 Education Opportunities in Space Law: A Directory Note by the Secretariat In response to the recommendation of the Legal Subcommittee at its fifty-sixth session, in 2017, the Office for Outer Space Affairs updated the Directory of education opportunities in space law. The Directory contains information on the respective institutions’ areas of specialization, educational programmes offered, facilities available, prerequisite qualifications, financial information, fellowship opportunities and opportunities for international cooperation, as well as reference to educational material easily available on the internet. Addresses and contact points for further information are included. The updated Directory is also being made available on the website of the Office for Outer Space Affairs (www.unoosa.org). V.18-02328 (E) *1802328* A/AC.105/C.2/2018/CRP.11 EDUCATION OPPORTUNITIES IN SPACE LAW A Directory 2018 edition 2/39 V.18-02328 A/AC.105/C.2/2018/CRP.11 Introduction The increasing number of States involved in space activities has emphasized the need for effective laws and policies on space activities not just on an international level, but also on the national level. The successful operation of space law, policies and institutions in a country relies on the presence of suitable professionals. Institutions that address the subject of space law and policy play an important role in promoting national expertise and capacity in this field. In response to the recommendation of the Legal Subcommittee of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space at its forty-second session, in 2003, the Office for Outer Space Affairs invited a number of institutions to provide the Office with information on their programmes relating to space law.