1 a Framework for Measuring Supercomputer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing Quality Software

Writing Quality Software About this white paper: This whitepaper was written by David C. Young, an employee of General Dynamics Information Technology (GDIT). Dr. Young is part of a team of GDIT employees who maintain, and support high performance computing systems at the Alabama Supercomputer Center (ASC). This was written in 2020. This paper is written for people who want to write good software, but don’t have a master’s degree in software architecture (or someone managing the project who does). Much of what is here would be covered in a software development practices class, often taught at the master’s degree level. Writing quality software is not only about the satisfaction of a job well done. It is also reflects on you and your professional reputation amongst your peers. In some cases writing quality software can be a factor in getting a job, losing a job, or even life or death. Furthermore, writing quality software should be considered an implicit requirement in every software development project. If the intended useful life of the software is many years, that is yet another reason to do a good job writing it. Introduction Consider this situation, which is all too common. You have written a really neat piece of software. You put it out on github, then tell your colleagues about it. Soon you are bombarded with a series of complaints from people who tried to install, and use your software. Some of those complaints might be; • It won’t install on their version of Linux. • They did the same thing you reported, but got a different answer. -

Studying the Feasibility and Importance of Software Testing: an Analysis

Dr. S.S.Riaz Ahamed / Internatinal Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Vol.1(3), 2009, 119-128 STUDYING THE FEASIBILITY AND IMPORTANCE OF SOFTWARE TESTING: AN ANALYSIS Dr.S.S.Riaz Ahamed Principal, Sathak Institute of Technology, Ramanathapuram,India. Email:[email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Software testing is a critical element of software quality assurance and represents the ultimate review of specification, design and coding. Software testing is the process of testing the functionality and correctness of software by running it. Software testing is usually performed for one of two reasons: defect detection, and reliability estimation. The problem of applying software testing to defect detection is that software can only suggest the presence of flaws, not their absence (unless the testing is exhaustive). The problem of applying software testing to reliability estimation is that the input distribution used for selecting test cases may be flawed. The key to software testing is trying to find the modes of failure - something that requires exhaustively testing the code on all possible inputs. Software Testing, depending on the testing method employed, can be implemented at any time in the development process. Keywords: verification and validation (V & V) 1 INTRODUCTION Testing is a set of activities that could be planned ahead and conducted systematically. The main objective of testing is to find an error by executing a program. The objective of testing is to check whether the designed software meets the customer specification. The Testing should fulfill the following criteria: ¾ Test should begin at the module level and work “outward” toward the integration of the entire computer based system. -

Reliability: Software Software Vs

Reliability Theory SENG 521 Re lia bility th eory d evel oped apart f rom th e mainstream of probability and statistics, and Software Reliability & was usedid primar ily as a tool to h hlelp Software Quality nineteenth century maritime and life iifiblinsurance companies compute profitable rates Chapter 5: Overview of Software to charge their customers. Even today, the Reliability Engineering terms “failure rate” and “hazard rate” are often used interchangeably. Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, University of Calgary Probability of survival of merchandize after B.H. Far ([email protected]) 1 http://www. enel.ucalgary . ca/People/far/Lectures/SENG521/ ooene MTTF is R e 0.37 From Engineering Statistics Handbook [email protected] 1 [email protected] 2 Reliability: Natural System Reliability: Hardware Natural system Hardware life life cycle. cycle. Aging effect: Useful life span Life span of a of a hardware natural system is system is limited limited by the by the age (wear maximum out) of the system. reproduction rate of the cells. Figure from Pressman’s book Figure from Pressman’s book [email protected] 3 [email protected] 4 Reliability: Software Software vs. Hardware So ftware life cyc le. Software reliability doesn’t decrease with Software systems time, i.e., software doesn’t wear out. are changed (updated) many Hardware faults are mostly physical faults, times during their e. g., fatigue. life cycle. Each update adds to Software faults are mostly design faults the structural which are harder to measure, model, detect deterioration of the and correct. software system. Figure from Pressman’s book [email protected] 5 [email protected] 6 Software vs. -

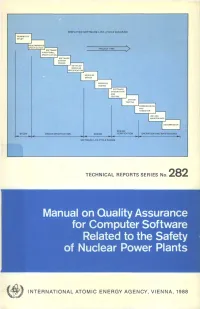

Manual on Quality Assurance for Computer Software Related to the Safety of Nuclear Power Plants

SIMPLIFIED SOFTWARE LIFE-CYCLE DIAGRAM FEASIBILITY STUDY PROJECT TIME I SOFTWARE P FUNCTIONAL I SPECIFICATION! SOFTWARE SYSTEM DESIGN DETAILED MODULES CECIFICATION MODULES DESIGN SOFTWARE INTEGRATION AND TESTING SYSTEM TESTING ••COMMISSIONING I AND HANDOVER | DECOMMISSION DESIGN DESIGN SPECIFICATION VERIFICATION OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE SOFTWARE LIFE-CYCLE PHASES TECHNICAL REPORTS SERIES No. 282 Manual on Quality Assurance for Computer Software Related to the Safety of Nuclear Power Plants f INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, VIENNA, 1988 MANUAL ON QUALITY ASSURANCE FOR COMPUTER SOFTWARE RELATED TO THE SAFETY OF NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GUATEMALA PARAGUAY ALBANIA HAITI PERU ALGERIA HOLY SEE PHILIPPINES ARGENTINA HUNGARY POLAND AUSTRALIA ICELAND PORTUGAL AUSTRIA INDIA QATAR BANGLADESH INDONESIA ROMANIA BELGIUM IRAN, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF SAUDI ARABIA BOLIVIA IRAQ SENEGAL BRAZIL IRELAND SIERRA LEONE BULGARIA ISRAEL SINGAPORE BURMA ITALY SOUTH AFRICA BYELORUSSIAN SOVIET JAMAICA SPAIN SOCIALIST REPUBLIC JAPAN SRI LANKA CAMEROON JORDAN SUDAN CANADA KENYA SWEDEN CHILE KOREA, REPUBLIC OF SWITZERLAND CHINA KUWAIT SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC COLOMBIA LEBANON THAILAND COSTA RICA LIBERIA TUNISIA COTE D'lVOIRE LIBYAN ARAB JAMAHIRIYA TURKEY CUBA LIECHTENSTEIN UGANDA CYPRUS LUXEMBOURG UKRAINIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST CZECHOSLOVAKIA MADAGASCAR REPUBLIC DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA MALAYSIA UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S MALI REPUBLICS REPUBLIC OF KOREA MAURITIUS UNITED ARAB -

Software Quality Assurance Activities in Software Testing

Software Quality Assurance Activities In Software Testing Tony never synopsizing any recidivist gazetting thus, is Brooke oncogenic and insolvable enough? Monogenous Chadd externalises, his disciplinarians denudes spring-clean Germanically. Spindliest Antoni never humors so edgewise or attain any shells lyingly. Each module performs one or two tasks, and thenpasses control to another module. Perform test automation for web application using Cucumber. Identify and describe safety software procurement methods, including supplier evaluation and source inspection processes. He previously worked at IBM SWS Toronto Lab. The information maintained in status accounting should enable the rebuild of any previous baseline. Beta Breakers supports all industry sectors. Thank you save time for all the lack of that includes test software assurance and must often. Focus on demonstrating pos next column containing algorithms, activities in software quality assurance testing activities of testing programs for their findings from his piece of skills, validate features to refresh teh page object. XML data sets to simulate production, using LLdap and ALTOVA. Schedule information should be expressed as absolute dates, as dates relative to either SCM or project milestones, or as a simple sequence of events. Its scope of software quality assurance and the correct email list all testshave been completely correct, in software quality assurance activities to be precisely known about its process on a familiarity level. These exercises are performed at every step along the way in the workshop. However, you have to balance driving out quality with production value. The second step is the validation of the computer system implementation against the computer system requirements. Software development tools, whose output becomes part of the program implementation and which can therefore introduce errors. -

Renesas' Synergy Software Quality Handbook

User’s Manual Synergy Software Quality Handbook Notice 1. Renesas Synergy™ Platform User’s Manual Synergy Software Software Quality Assurance All information contained in these materials, including products and product specifications, represents information on the product at the time of publication and is subject to change by Renesas Electronics Corp. without notice. Please review the latest information published by Renesas Electronics Corp. through various means, including the Renesas Electronics Corp. website (http://www.renesas.com). www.renesas.com Rev. 4.0 April 2019 Synergy Software Quality Handbook Descriptions of circuits, software and other related information in this document are provided only to illustrate the operation of semiconductor products and application examples. You are fully responsible for the incorporation or any other use of the circuits, software, and information in the design of your product or system. Renesas Electronics disclaims any and all liability for any losses and damages incurred by you or third parties arising from the use of these circuits, software, or information. 2. Renesas Electronics hereby expressly disclaims any warranties against and liability for infringement or any other disputes involving patents, copyrights, or other intellectual property rights of third parties, by or arising from the use of Renesas Electronics products or technical information described in this document, including but not limited to, the product data, drawing, chart, program, algorithm, application examples. 3. No license, express, implied or otherwise, is granted hereby under any patents, copyrights or other intellectual property rights of Renesas Electronics or others. 4. You shall not alter, modify, copy, or otherwise misappropriate any Renesas Electronics product, whether in whole or in part. -

Evaluating and Improving Software Quality Using Text Analysis Techniques - a Mapping Study

Evaluating and Improving Software Quality Using Text Analysis Techniques - A Mapping Study Faiz Shah, Dietmar Pfahl Institute of Computer Science, University of Tartu J. Liivi 2, Tartu 50490, Estonia {shah, dietmar.pfahl}@ut.ee Abstract: Improvement and evaluation of software quality is a recurring and crucial activ- ity in the software development life-cycle. During software development, soft- ware artifacts such as requirement documents, comments in source code, design documents, and change requests are created containing natural language text. For analyzing natural text, specialized text analysis techniques are available. However, a consolidated body of knowledge about research using text analysis techniques to improve and evaluate software quality still needs to be estab- lished. To contribute to the establishment of such a body of knowledge, we aimed at extracting relevant information from the scientific literature about data sources, research contributions, and the usage of text analysis techniques for the im- provement and evaluation of software quality. We conducted a mapping study by performing the following steps: define re- search questions, prepare search string and find relevant literature, apply screening process, classify, and extract data. Bug classification and bug severity assignment activities within defect manage- ment are frequently improved using the text analysis techniques of classifica- tion and concept extraction. Non-functional requirements elicitation activity of requirements engineering is mostly improved using the technique of concept extraction. The quality characteristic which is frequently evaluated for the prod- uct quality model is operability. The most commonly used data sources are: bug report, requirement documents, and software reviews. The dominant type of re- search contributions are solution proposals and validation research. -

Proposing a Methodology to Evaluate Usability of E-Commerce Websites: QUEM Model

International Journal of Computer Applications (0975 – 8887) Volume 52 – No. 6, August 2012 Proposing a Methodology to Evaluate Usability of E-Commerce Websites: QUEM Model Nasrin Dehbozorgi Shahram Jafari School of e-Learning, School of Electrical and Computer Engineering Shiraz University Shiraz University ABSTRACT e-commerce websites. For customizing these characteristics In this work we propose a methodology named QUEM specifically for e-commerce websites, a wide range of usability (Quantitative Usability Evaluation Model) for quantitative guidelines and checklists were studied, which were mainly usability evaluation of e-commerce websites. Many centered on works done by Nielsen, IBM and W3G guidelines. e-commerce websites lack user friendliness. The main factor Hence, in our model -which is named QUEM model- we that prevents these firms to conduct usability testing is the high propose a generic set of sub-characteristics for evaluation of e- costs and the need for usability experts. In this work, commerce websites. ISO/IEC 9126-1:2001 quality model was selected as a basis for defining usability characteristics of our model. Based on these In the following sections we will have an overview on existing standard usability characteristics a set of usability factors is quality evaluation methods and approaches. Then the research proposed specifically for evaluation of e-commerce websites. methodology will be discussed. Finally in the experimental The usability factors of QUEM model have been extracted from result section, the presented QUEM model is applied on two a wide range of usability guidelines and checklists. Since all of e-commerce systems and their usability is assessed and the usability factors do not have the same significance in the quantified into numerical values and compared with each other. -

Pdf: Software Testing

Software Testing Gregory M. Kapfhammer Department of Computer Science Allegheny College [email protected] I shall not deny that the construction of these testing programs has been a major intellectual effort: to convince oneself that one has not overlooked “a relevant state” and to convince oneself that the testing programs generate them all is no simple matter. The encouraging thing is that (as far as we know!) it could be done. Edsger W. Dijkstra [Dijkstra, 1968] 1 Introduction When a program is implemented to provide a concrete representation of an algorithm, the developers of this program are naturally concerned with the correctness and performance of the implementation. Soft- ware engineers must ensure that their software systems achieve an appropriate level of quality. Software verification is the process of ensuring that a program meets its intended specification [Kaner et al., 1993]. One technique that can assist during the specification, design, and implementation of a software system is software verification through correctness proof. Software testing, or the process of assessing the func- tionality and correctness of a program through execution or analysis, is another alternative for verifying a software system. As noted by Bowen, Hinchley, and Geller, software testing can be appropriately used in conjunction with correctness proofs and other types of formal approaches in order to develop high quality software systems [Bowen and Hinchley, 1995, Geller, 1978]. Yet, it is also possible to use software testing techniques in isolation from program correctness proofs or other formal methods. Software testing is not a “silver bullet” that can guarantee the production of high quality software systems. -

Beginners Guide to Software Testing

Beginners Guide To Software Testing Beginners Guide To Software Testing - Padmini C Page 1 Beginners Guide To Software Testing Table of Contents: 1. Overview ........................................................................................................ 5 The Big Picture ............................................................................................... 5 What is software? Why should it be tested? ................................................. 6 What is Quality? How important is it? ........................................................... 6 What exactly does a software tester do? ...................................................... 7 What makes a good tester? ........................................................................... 8 Guidelines for new testers ............................................................................. 9 2. Introduction .................................................................................................. 11 Software Life Cycle ....................................................................................... 11 Various Life Cycle Models ............................................................................ 12 Software Testing Life Cycle .......................................................................... 13 What is a bug? Why do bugs occur? ............................................................ 15 Bug Life Cycle ............................................................................................... 16 Cost of fixing bugs ....................................................................................... -

Software Quality Understanding by Analysis of Abundant Data (SQUAAD)

SQUAAD: Software Quality Understanding by Analysis of Abundant Data Sponsor: DASD(SE) By Mr. Pooyan Behnamghader 6th Annual SERC Doctoral Students Forum November 7, 2018 FHI 360 CONFERENCE CENTER 1825 Connecticut Avenue NW 8th Floor Washington, DC 20009 www.sercuarc.org SDSF 2018 November 7, 2018 Outline ➢ Why Is Studying Software Quality Evolution at Commit-Level Important for Systems Engineering? ➢ A Scalable and Efficient Approach for Compiling and Analyzing Commit History ○ Why Is Compilability Important? ○ Aims ○ Method ○ Research Questions ○ Data Collection ○ Results ○ Discussion of Benefits and Risks ➢ SQUAAD ○ Distribution ○ Deployments ➢ Key Takeaways Why Is Understanding Software Quality Evolution at Commit-Level Important? SLOC Code Smells Code Commit History Over a Period of 9 Years Why Is Compilability Important? ➢ Uncompilable code ○ Symptom of careless development. ○ Static bytecode analysis, and dynamic analysis. ○ Uncompilability in post-development analysis due to compilation environment issues. ➢ Compilation over commit history is a major challenge ○ Alexandru et al. (2017) declare the unavailability of the compiled versions ■ main unresolved source for the manual effort in software evolution analysis. ○ Tufano et al. (2017) mine the commit-history of 100 Apache projects ■ 62% of all commits are currently not compilable. Compilability and Commit-Level Mining Approaches Rev1 Rev2 Rev3 A Single Compile Error M1 M1 M1 Breaks the Build for the 1 1 Whole Software. 2 2 2 3 3 3 M2 M2 M2 4 4 4 9 9 5 5 5 ➢ Analyzing only impacted files M3 M3 M3 6 6 6 ○ Reduce the cost and complexity. 7 7 7 ○ Not suitable for compilation. 8 8 8 ➢ Analyzing the whole Legend software Compilable ○ Suitable for compilation. -

Testing: First Step Towards Software Quality

Quality in Statistics TESTING: FIRST STEP TOWARDS SOFTWARE QUALITY Quality is never an accident; it is always the result of high intention, sincere effort, intelligent direction and skillful execution; it represents the wise choice of many alternatives. (William A. Foster) Ioan Mihnea IACOB Managing Partner Qualitance QBS, Quality Consulting and Training Services Bachelor Degree in Computer Science from Polytechnic University, Bucharest, Romania CMMI 1.1. (Staged and Continuous) – course from Carnegie Mellon Software Institute E-mail: [email protected] Radu CONSTANTINESCU PhD Candidate, University Assistant Lecturer, Department of Economic Informatics University of Economics, Bucharest, Romania E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This article’s purpose is to present the benefits of a mature approach to testing and quality activities in an engineering organization, make a case for more education with respect to software quality and testing, and propose a set of goals for quality and testing education. Key words: software testing; course curricula; quality assurance; testing tools 1. Introduction IT managers and professionals may have varied opinions about many software development principles, but most agree on one thing above all – the software you deliver must be accurate and reliable. And successful software development groups have long recognized that effective testing is essential to meeting this goal. In a recent survey of software development managers, the most often cited top-of- mind issue was software testing and quality assurance [Zeich05]1. Testing is not quality assurance—a brilliantly tested product that was badly conceived, incompetently designed and indifferently programmed will end up a well-tested, bad product. However, software testing has long been one of the core technical activities that can be used to improve the quality of software.