Biodiversity, Yield, and Shade Coffee Certification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Do Atmospheres Change Over Time? the Greenhouse Effect

Activity #5 How Do Atmospheres Change Over Time? The Greenhouse Effect [Adult] Adapted from: Global Warming & The Greenhouse Effect, Great Explorations in Math and Science (GEMS) Lawrence Hall of Science, 1997, by the Regents of the University of California ISBN: 0-912511-75-3. Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of SETI Institute. 1. Introduction In this activity, Cadettes will observe how the greenhouse effect can change an atmosphere on Mars or on Earth. They will “Think like a scientist. Be a scientist!” 2. Science Objectives You will: • construct models to test ideas about processes that cannot be directly studied on Earth or Mars; • appreciate that the atmosphere is a large and complex system, so experiments concerning it are difficult to perform; and • use skills you have learned about atmospheric composition and apply that knowledge to new situations. 3. Materials For each group of 4–6 Cadettes. • [2] 2 liter (0.5 gal) clear soda bottles with labels removed and tops cut off. These are the Atmosphere Model Chambers. Advance preparation required (see page 2). • [1] pair of scissors for constructing a set of Atmosphere Model Chambers • [1] black permanent marker for constructing a set of Atmosphere Model Chambers • [2] identical thermometers, one for each chamber; view on Amazon.com: http://tinyurl.com/lkrvzvq • sufficient cardboard to prepare backing for each thermometer • 5–10 cm (about 4 in) of clear tape to attach thermometers to cardboard and to inside of each chamber • [1] piece of plastic wrap approximately 15 cm x 15 cm (6 x 6 in) • [1] rubber band large enough to fit the circumference of chamber and secure plastic wrap • chart of electromagnetic spectrum of light (EMS); print in advance • 250-watt infrared heat lamp (bulb) in a fixture with hood. -

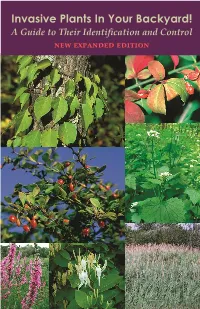

Invasive Plants in Your Backyard!

Invasive Plants In Your Backyard! A Guide to Their Identification and Control new expanded edition Do you know what plants are growing in your yard? Chances are very good that along with your favorite flowers and shrubs, there are non‐native invasives on your property. Non‐native invasives are aggressive exotic plants introduced intentionally for their ornamental value, or accidentally by hitchhiking with people or products. They thrive in our growing conditions, and with no natural enemies have nothing to check their rapid spread. The environmental costs of invasives are great – they crowd out native vegetation and reduce biological diversity, can change how entire ecosystems function, and pose a threat Invasive Morrow’s honeysuckle (S. Leicht, to endangered species. University of Connecticut, bugwood.org) Several organizations in Connecticut are hard at work preventing the spread of invasives, including the Invasive Plant Council, the Invasive Plant Working Group, and the Invasive Plant Atlas of New England. They maintain an official list of invasive and potentially invasive plants, promote invasives eradication, and have helped establish legislation restricting the sale of invasives. Should I be concerned about invasives on my property? Invasive plants can be a major nuisance right in your own backyard. They can kill your favorite trees, show up in your gardens, and overrun your lawn. And, because it can be costly to remove them, they can even lower the value of your property. What’s more, invasive plants can escape to nearby parks, open spaces and natural areas. What should I do if there are invasives on my property? If you find invasive plants on your property they should be removed before the infestation worsens. -

West Lake Woven Wood Shade Section

West Lake Woven Wood Shade Section Effective April 15, 2014 Save a life: "Install Safety Tension Devices!" Woven Wood Measuring Instructions Measuring Inside Mount (IB) Shades: Measure the exact width (A) and length (B) of the window opening as shown. The factory will deduct ½” overall from the window width for clearance. On all inside mount shades, a small light gap will be visible. Measuring Outside Mount (OB) Shades: Measure the exact width (A) and length (B) of the window opening you wish to cover. The shade should cover the window opening by at least 2” on both the width and length. To cover a window sill, provide a measurement (C) beyond the sill. Outside Mount Inside Mount Measuring Arch Top Valances for Woven Wood Shades: For inside mount shades, measure the exact width and tallest length inside the window opening. For outside mount shades, measure the desired width and tallest length. Make sure to measure the length of outside mount shades at its tallest point. Arch Top woven wood shades must be perfect arches where the length equals ½ the width. For arch top valances, measure dimensions A, X, & Y. For pricing, use the width and tallest length measurement. Make sure to add the arch top shade surcharge. Measuring Angled Shades: It is critical to measure all four sides of the window opening. For inside mount shades, measure the inside of the window opening and for outside mount shades, add the desired overlap. Measure the slope angle with a protractor and provide the angle in degrees. Indicate all measurements on a template to be sent to the factory. -

8040 Introduction to Natural Resources and Ecology Systems

Introduction to Natural Resources and Ecology Systems 8040/36 weeks Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Course Description ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Task Essentials Table .................................................................................................................................... 2 Curriculum Framework ................................................................................................................................. 6 Exploring Leadership Skills through FFA ................................................................................................... 6 Exploring Leadership Opportunities through FFA ....................................................................................... 7 Understanding Natural Resource Management ............................................................................................ 9 Protecting the Environment ........................................................................................................................ 15 Managing Forest Resources ........................................................................................................................ 25 Managing Wildlife Resources .................................................................................................................... -

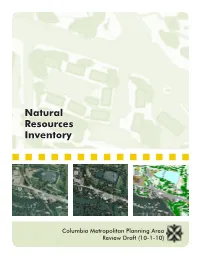

Natural Resources Inventory

Natural Resources Inventory Columbia Metropolitan Planning Area Review Draft (10-1-10) NATURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY Review Draft (10-1-10) City of Columbia, Missouri October 1, 2010 - Blank - Preface for Review Document The NRI area covers the Metropolitan Planning Area defined by the Columbia Area Transportation Study Organization (CATSO), which is the local metropolitan planning organization. The information contained in the Natural Resources Inventory document has been compiled from a host of public sources. The primary data focus of the NRI has been on land cover and tree canopy, which are the product of the classification work completed by the University of Missouri Geographic Resource Center using 2007 imagery acquired for this project by the City of Columbia. The NRI uses the area’s watersheds as the geographic basis for the data inventory. Landscape features cataloged include slopes, streams, soils, and vegetation. The impacts of regulations that manage the landscape and natural resources have been cataloged; including the characteristics of the built environment and the relationship to undeveloped property. Planning Level of Detail NRI data is designed to support planning and policy level analysis. Not all the geographic data created for the Natural Resources Inventory can be used for accurate parcel level mapping. The goal is to produce seamless datasets with a spatial quality to support parcel level mapping to apply NRI data to identify the individual property impacts. There are limitations to the data that need to be made clear to avoid misinterpretations. Stormwater Buffers: The buffer data used in the NRI are estimates based upon the stream centerlines, not the high water mark specified in City and County stormwater regulations. -

William House Woven Wood Shade Collection

SUGGESTED RETAIL PRICING SEPTEMBER, 2015* WILLIAM HOUSE WOVEN WOOD SHADE COLLECTION *THIS VERSION IS AN ADDENDUM, WHICH CONTAINS SOME PATTERN DISCONTINUATIONS (JAN. 2017) TEXTON.COM 800-442-1540 FAX: 972-276-5104 SEPTEMBER, 2015 MEASURING INSTRUCTIONS MEASURE EACH WINDOW INDIVIDUALLY AS SIZES MAY VARY. RECORD WIDTH FIRST, THEN HEIGHT (LENGTH) TO THE NEAREST 1/8”. MEASURE WIDTH FROM LEFT TO RIGHT, HEIGHT FROM TOP TO BOTTOM USING A METAL TAPE MEASURE. PLEASE DO NOT USE A CLOTH TAPE! INSIDE MOUNT INSIDE MOUNT BLINDS ARE INSTALLED INSIDE THE WINDOW FRAME. 1. MEASURE THE EXACT INSIDE WIDTH OF WINDOW FRAME FROM ONE INSIDE EDGE TO THE OTHER. TAKE THREE MEASURE- MENTS, ONE NEAR THE TOP, ONE IN THE CENTER AND ONE NEAR THE BOTTOM. RECORD THE NARROWEST MEASUREMENT. 2. MEASURE THE EXACT HEIGHT IN THREE PLACES, LEFT, CENTER AND RIGHT FROM TOP EDGE OF OPENING TO TOP OF SILL. RE- CORD THE LONGEST MEASUREMENT FOR WOVEN WOOD SHADES. 3. DO NOT TAKE DEDUCTIONS ON INSIDE MOUNT MEASUREMENTS. THE FACTORY WILL TAKE AN 1/2“ ALLOWANCES FOR 4. OPERATING CLEARANCE. 5. MEASURE THE WINDOW DIAGONALLY IN TWO PLACES. IF THE TWO DIAGONAL MEASUREMENTS ARE NOT THE SAME, WE SUGGEST AN OUTSIDE MOUNT APPLICATION FOR THE BEST SHADE PERFORMANCE AND APPEARANCE. OUTSIDE MOUNT OUTSIDE MOUNT BLINDS ARE INSTALLED OUTSIDE THE WINDOW FRAME, COVERING AN AREA LARGER THAN THE WINDOW ITSELF. 1. MEASURE THE EXACT WIDTH OF AREA TO BE COVERED. BE CERTAIN THE MEASUREMENT OVERLAPS THE WINDOW OPENING BY 2. AT LEAST 1 1/2” ON EACH SIDE TO ENSURE PRIVACY AND LIGHT CONTROL. -

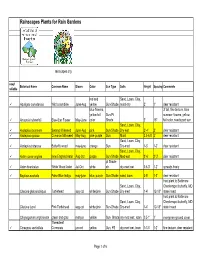

Rainscapes Plants for Rain Gardens

Rainscapes Plants for Rain Gardens rainscapes.org easy/ Botanical Name Common Name Bloom Color Sun Type Soils Height Spacing Comments reliable red and Sand, Loam, Clay, 9 Aquiligea canadensis Wild columbine June-Aug yellow Sun-Shade moist-dry 2' 1' deer resistant blue flowers, 3' tall, fine texture, blue yellow fall Sun-Pt summer flowers, yellow 9 Amsonia hubrechtii Blue-Star Flower May-June color Shade 2' 18" fall color, needs part sun Sand, Loam, Clay, 9 Asclepias incarnata Swamp Milkweed June-Aug pink Sun-Shade Dry-wet 2'-4' 2' deer resistant 9 Asclepias syriaca Common Milkweed May-Aug pale purple Sun Moist 3.5-6.5' 2' deer resistant Sand, Loam, Clay, 9 Asclepias tuberosa Butterfly weed may-june orange Sun Dry-med 1-3' 1-2' deer resistant Sand, Loam, Clay, 9 Aster novae angliae New England Aster Aug-Oct purple Sun-Shade Med-wet 2'-6' 2'-3' deer resistant pt Shade- 9 Aster divaricatus White Wood Aster Jul-Oct white sh dry-med wet 0.5-3' 1-2' spreads freely 9 Baptisia australis False Blue Indigo may-june blue, purple Sun-Shade sand, loam 3-5' 1-2' deer resistant host plant to Baltimore Sand, Loam, Clay, Checkerspot butterfly, MD Chelone glabra/obliqua Turtlehead aug-oct white/pink Sun-Shade Dry-med 1-4' 12-18" state insect host plant to Baltimore Sand, Loam, Clay, Checkerspot butterfly, MD Chelone lyonii Pink Turtlehead aug-oct white/pink Sun-Shade Dry-med 1-4' 12-18" state insect Chrysogonum virginianum green and gold mar-jun yellow Sun- Shade dry-med wet; loam 0.5-1' 1' evergreen ground cover Threadleaf 9 Coreopsis verticillata Coreopsis -

Year Round Gardening Shade V Sun Get It Right! Fredricka Bogardus, Colorado Master Gardener

Year Round Gardening Shade v Sun get it right! Fredricka Bogardus, Colorado Master Gardener The light available to a plant will directly impact its’ success in your garden. Understanding the light conditions before you select plants will make you a savvy buyer. Most plant tags with have some indication of whether the plant requires, full sun, part sun, part shade or shade. If you aren’t sure, take the time to check before you buy. These terms have a general meaning in horticulture. Full sun is 6 or more hours of direct sunlight per day, part sun is is 4 -6 hours per day. Partial shade is 2-4 hours of direct sun per day, shade means less than 2 hours of direct sun. A useful exercise is to actually measure the amount of direct sun each hour, record it for several different parts of your garden. Start at 7 am and go to 7 pm preferably in June or July. You may be very surprised at how much more understanding you will gain. You can purchase instruments for measuring the light, but for the home gardener your observation is probably just as useful. Another factor is the time of day of the sun. Shade plants are more likely to tolerate some sun in the early morning, but not the hot afternoon sun. Plants that get too much sun can appear bleached, or even scorched. If you notice these signs either relocate the plant or create some additional shade with a structure or perhaps a shrub or tree nearby. Plants that do not get enough sun may not flower abundantly, and will look spindly and weak. -

Throwing Shade

throwing 10 Sunny States BlockingShade 2018 Edition Distributed Solar Development By Greer Ryan Center for Biological Diversity April 2018 Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................1 Additional Report Highlights ......................................................3 Introduction ..............................................................................4 Key state-level distributed-solar policies and barriers ....................6 Renewable Portfolio Standards and Solar Carveouts .......................................................... 8 Net Metering .................................................................................................................... 9 Community Solar ............................................................................................................. 11 Interconnection Standards ............................................................................................... 12 Third-party Ownership ..................................................................................................... 13 Solar Rights Laws ........................................................................................................... 14 10 Sunny States Blocking Distributed Solar ..............................15 Alabama ......................................................................................................................... 16 Florida .......................................................................................................................... -

March 18, 2021 Re: Fossil Fuels and False Solutions in 2035 Clean Energy Standard Targets Dear Member of Congress: on Behalf Of

March 18, 2021 Re: Fossil Fuels and False Solutions in 2035 Clean Energy Standard targets Dear Member of Congress: On behalf of our millions of members and activists nationwide, we write to express our concerns about the role of fossil fuels and other false solutions in recent proposals to achieve 100 percent clean energy by 2035. Although we applaud this new and genuinely ambitious timeline, technology-neutral frameworks pose an unacceptable risk to communities and the climate. The Clean Energy Standards (CES) now under discussion in Congress should rigorously define clean energy to include proven solutions like wind, solar, storage and efficiency—and exclude all fossil fuels and other false solutions. Sacrificing the very definition of “clean” in order to achieve 100 percent clean energy is self-defeating. The CLEAN Future Act (H.R. 1512) is a prime example of the type of half-measure we must avoid. The CES in the newly proposed bill is defined broadly enough to allow “natural” gas (fossil gas), biomass, and nuclear power to qualify. These false solutions are not clean energy and undermine efforts both to reduce emissions and protect communities from pollution. This iteration of the CLEAN Future Act includes encouraging environmental justice provisions that would benefit communities disproportionately exposed to pollution and climate impacts. That said, any legislative proposal that includes the promotion or facilitation of false energy solutions effectively debases any and all provisions, however strong, dedicated to increasing and centering environmental justice. Unfortunately, the legislation, as written, contradicts itself - recognizing the importance of reducing, removing, and preventing additional pollution in disadvantaged and vulnerable communities on the one hand, and promoting false climate solutions that do not stop emissions or other pollution at their source on the other. -

Maple Shade Water Department Source Water Assessment Summary

Maple Shade Water Department Source Water Assessment Summary A State Review of Potential Contamination Sources Near Your Drinking Water The Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has conducted an assessment of the water sources that supply each public water system in the state, including yours. The goal of this assessment was to measure each system’s susceptibility to contamination, not actual (if any) contamination measured in a water supply system. The assessment of your water system, the Maple Shade Water Department, involved: Identifying the area (known as the source water assessment area) that supplies water to your public drinking water system; Inventorying any significant potential sources of contamination in the area; and Analyzing how susceptible the drinking water source is to the potential sources of contamination. DEP evaluated the susceptibility of all public water systems to eight categories of contaminants. These contaminant categories are explained, along with a summary of the results for your water system, on page 3. Page 4 contains a map of your water system’s source water assessment area. A public water system’s susceptibility rating (L for low, M for medium or H for high) is a combination of two factors. H, M, and L ratings are based on the potential for a contaminant to be at or above 50% of the Drinking Water Standard or MCL (H), between 10 and 50% of the standard (M) and less than 10% of the standard (L). How “sensitive” the water supply is to contamination. For example, a shallow well or surface water source, like a reservoir, would be more exposed to contamination from the surface or above ground than a very deep well. -

IV.A.2 Aesthetics Shade and Shadow

! IV. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ANALYSIS A. AESTHETICS 2. SHADE AND SHADOW ! 1. INTRODUCTION The following analysis of the Modified Project’s potential impacts associated with aesthetics (shade and shadow) is based on the analysis provided in Section IV.A Aesthetics of the Certified EIR for the CRA Approved Project. This section of the Draft Supplemental EIR determines whether the Modified Project would result in significant impacts related to aesthetics (shade and shadow) not previously identified in the CRA Approved Project’s Certified EIR and provides updates, as necessary, to account for any physical or regulatory changes to the circumstances under which the Modified Project is being undertaken. One such regulatory change, discussed in further detail below in the Regulatory Framework subsection, involves Senate Bill 743 (SB 743). Pursuant to SB 743, mixed-use residential projects located on infill development sites within Transit Priority Areas shall not be considered to have significant impacts on the environment related to aesthetics. Because the Modified Project is a mixed-use residential project located on an infill site within a Transit Priority Area as defined by CEQA and the City of Los Angeles has identified the Project Site as being within a Transit Priority Area,1 the Modified Project’s effects on aesthetic resources, including views/light and glare (discussed in further detail in Section IV.A.1, Views/Light and Glare), and shade and shadow, shall not be considered significant impacts on the environment. As such, the following analysis is presented for informational purposes only. The City of Los Angeles L.A. CEQA Thresholds Guide recognizes shade and shadow impacts as an environmental impact associated with aesthetics and visual resources.