Ung)-Initiated Dna Base Excision Repair in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis Final

CHARACTERIZATION OF ADENOSINE NUCLEOSIDASE FROM ALASKA PEA SEEDS by Abdullah K. Shamsuddin A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Graduate Studies at Middle Tennessee State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Chemistry Middle Tennessee State University August 2015 Thesis Committee: Dr. Paul C. Kline, Chair Dr. Donald A. Burden Dr. Kevin L. Bicker I dedicate this research to my parents, my sisters, and my brother. I love you all. ii" " ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Paul C. Kline, for his guidance, support, and ongoing encouragement throughout this project. I also wish to thank my committee members, Dr. Donald A. Burden and Dr. Kevin L. Bicker, for their advice and insightful comments. In addition, I would like to thank all the staff and faculty of the Department of Chemistry for their contribution to the success of this study. Lastly, I wish to thank my family and my friends, without whom none of my accomplishments would have been possible. Thank you for you endless support, concern, love, and prayer. iii" " ABSTRACT Adenosine nucleosidase was purified from Alaska pea seeds five days after germination. A 4-fold purification has been reached with a 1.3 % recovery. The subunit molecular weight of adenosine nucleosidase was determined by mass spectrometry to be 26,103 daltons. The number of subunits was 1. The Michaelis constant, Km, and the maximum velocity, V max, for adenosine were determined to be 137 ± 48 µM, and 0.34 ± 0.02 µM/min respectively. -

Pyrimidine Base Degradation in Cultured Murine C-1300 Neuroblastoma Cells and in Situ Tumors

Pyrimidine base degradation in cultured murine C-1300 neuroblastoma cells and in situ tumors. M Tuchman, … , M L Ramnaraine, B L Mirkin J Clin Invest. 1988;81(2):425-430. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI113336. Research Article Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD), the initial, rate-limiting step in pyrimidine degradation, was studied in two cell lines of murine neuroblastoma (MNB-T1 and MNB-T2) that were derived from C-1300 MNB tumor carried in A/J mice. The MNB-T2 (low malignancy) cell line was originally derived from the in situ tumor and carried in tissue culture for more than 100 passages; the MNB-T1 (high malignancy) line consisted of a new sub-culture that was also established from the in situ MNB tumor. DPD activity was determined in cytosolic preparations of MNB utilizing high performance liquid chromatography to separate the radiolabeled substrate ([2-14C]thymine) from [2-14C]dihydrothymine. The apparent affinity of DPD for NADPH in MNB cells (Km approximately 0.08 mM) was identical to that of A/J mouse brain and liver. The DPD activity of the high malignancy (MNB-T1) cell line was 14.3% of that observed in the low malignancy (MNB-T2) line. In situ tumors formed after implantation of high malignancy (MNB-T1) cells into A/J mice had only 25.2% of the DPD activity observed in tumors derived from low malignancy (MNB-T2) cells. When MNB-T2 cells were injected into naive A/J mice, tumors developed in only 68% of animals, the tumor growth rate was slow and a mortality of 20% was observed. -

(10) Patent No.: US 8119385 B2

US008119385B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,119,385 B2 Mathur et al. (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 21, 2012 (54) NUCLEICACIDS AND PROTEINS AND (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................ 435/212:530/350 METHODS FOR MAKING AND USING THEMI (58) Field of Classification Search ........................ None (75) Inventors: Eric J. Mathur, San Diego, CA (US); See application file for complete search history. Cathy Chang, San Diego, CA (US) (56) References Cited (73) Assignee: BP Corporation North America Inc., Houston, TX (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS c Mount, Bioinformatics, Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Har (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this bor New York, 2001, pp. 382-393.* patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Spencer et al., “Whole-Genome Sequence Variation among Multiple U.S.C. 154(b) by 689 days. Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa” J. Bacteriol. (2003) 185: 1316 1325. (21) Appl. No.: 11/817,403 Database Sequence GenBank Accession No. BZ569932 Dec. 17. 1-1. 2002. (22) PCT Fled: Mar. 3, 2006 Omiecinski et al., “Epoxide Hydrolase-Polymorphism and role in (86). PCT No.: PCT/US2OO6/OOT642 toxicology” Toxicol. Lett. (2000) 1.12: 365-370. S371 (c)(1), * cited by examiner (2), (4) Date: May 7, 2008 Primary Examiner — James Martinell (87) PCT Pub. No.: WO2006/096527 (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Kalim S. Fuzail PCT Pub. Date: Sep. 14, 2006 (57) ABSTRACT (65) Prior Publication Data The invention provides polypeptides, including enzymes, structural proteins and binding proteins, polynucleotides US 201O/OO11456A1 Jan. 14, 2010 encoding these polypeptides, and methods of making and using these polynucleotides and polypeptides. -

Induced Alterations in the Urine Metabolome in Cardiac Surgery

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Bretschneider solution- induced alterations in the urine metabolome in cardiac surgery Received: 16 August 2018 Accepted: 1 November 2018 patients Published: xx xx xxxx Cheng-Chia Lee1,3, Ya-Ju Hsieh 2, Shao-Wei Chen3,4, Shu-Hsuan Fu2, Chia-Wei Hsu 2, Chih-Ching Wu 2,5,6, Wei Han7, Yunong Li7, Tao Huan7, Yu-Sun Chang2,6,8, Jau-Song Yu2,9,10, Liang Li7, Chih-Hsiang Chang1,3 & Yi-Ting Chen 1,2,11,12 The development of Bretschneider’s histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate (HTK) cardioplegia solution represented a major advancement in cardiac surgery, ofering signifcant myocardial protection. However, metabolic changes induced by this additive in the whole body have not been systematically investigated. Using an untargeted mass spectrometry-based method to deeply explore the urine metabolome, we sought to provide a holistic and systematic view of metabolic perturbations occurred in patients receiving HTK. Prospective urine samples were collected from 100 patients who had undergone cardiac surgery, and metabolomic changes were profled using a high-performance chemical isotope labeling liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) method. A total of 14,642 peak pairs or metabolites were quantifed using diferential 13C-/12C-dansyl labeling LC-MS, which targets the amine/phenol submetabolome from urine specimens. We identifed 223 metabolites that showed signifcant concentration change (fold change > 5) and assembled several potential metabolic pathway maps derived from these dysregulated metabolites. Our data indicated upregulated histidine metabolism with subsequently increased glutamine/glutamate metabolism, altered purine and pyrimidine metabolism, and enhanced vitamin B6 metabolism in patients receiving HTK. -

Particular Metabolic Profile of Patient with Total

International Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Health Care Issue 5, Vol. 1 (Jan-Feb. 2015) Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ijphc/index.html ISSN 2249 – 5738 PARTICULAR METABOLIC PROFILE OF PATIENT WITH TOTAL DIHYDROPYRIMIDINE DEHYDROGENASE DEFICIENCY (DPD) Saif Eddine GAMAOUNa,b, Nissem ABDEJALLILa, Mhamed Ali HAMZAb, Saad SAGUEMa aLaboratory of Metabolic Biophysics, Professional and Applied Environmental Toxicology, Medicine faculty of Sousse, Mohamed Karoui street, Sousse 4002, Tunisia bDepartment of chemistry, sciences faculty of Monastir, Environment street, Monastir 5019, Tunisia *Author for correspondence at present address: Saif Eddine GAMAOUN Higher Institute of Technological Studies (ISET) Ksar Hellal-Hadj Ali Soua street-5070-Ksar Hellal,Tunisia Fonction : Engineer of analytical chemistry and instrumentation - Assistant teacher in ISET Ksar Hellal - Tunisia Tel.: (+216) 73 475 900 / (+216) 98 685 958 Fax: (+216) 73 475 163 E-mail: saifeddineg @ yahoo.fr ABSTRACT 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) remains one of the most used chemotherapeutics agents in the treatment of several types of cancers. Its use could nevertheless, raise a problem of pharmacovigilance. It may engender a very grave toxicity which can be fatal at certain patient's presenting an enzymatic deficit with dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD). The identification of the subjects at risk through the detection of a partial or total deficit before starting the treatment with 5-FU, could allow to adapt individually the prescribed dose, to optimize the therapeutic efficacy and reduce potential toxicities at expanding patients of a partial deficit to DPD. Such a screening would especially become more important when it is about a complete deficit in DPD. Such metabolic abnormality whose frequency is of the order of one per thousand, would indeed constitute a contraindication absolved from any chemotherapy with 5-FU (mortal toxicities). -

Possible Prediction of Adverse Reactions to Pyrimidine Chemotherapy from Urinary Pyrimidine Levels and a Case of Asymptomatic Adult Dihydropyrimidinuria1

Vol. 2, 1937-1 941, December 1996 Clinical Cancer Research 1937 Possible Prediction of Adverse Reactions to Pyrimidine Chemotherapy from Urinary Pyrimidine Levels and a Case of Asymptomatic Adult Dihydropyrimidinuria1 Katsuo Hayashi,2 Kiyoshi Kidouchi, INTRODUCTION Satoshi Sumi, Masashi Mizokami, Etsuro Onto, Pyrimidine chemotherapy agents such as 5-FU3 are used widely but can occasionally cause serious adverse reactions. In Kazunoni Kumada, Ryuzo Ueda, and pyrimidine metabolism, uracil and thymine are first converted to Yoshino Wada dihydropyrimidines (dihydrouracil and dihydrothymine) by Departments of Medicine [K. H., K. Ku.] and Pediatrics [K. Ki.], DPD and then are metabolized to 3-ureidopropionic acid and Nagoya City Higashi General Hospital, 2-23 Wakamizu 1-chome, 3-ureidoisobutyric acid, respectively, by dihydropyrimidinase. Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464, Japan, and Department of Pediatrics [S. S., These compounds are converted subsequently into 3-alanine Y. W.] and Second Department of Medicine [M. M., E. 0., R. U.], Nagoya City University Medical School. Nagoya, Japan and -arninoisobutyric acid, respectively ( 1). Because about 80% of an administered dose of 5-FU is degraded by this pathway, there is a possibility of adverse reactions occurring as ABSTRACT a result of DPD or dihydrophrimidinase deficiency. The value of Deficiency of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase or di- measuring peripheral blood monocyte DPD activity before ad- hydropyrimidinase, enzymes that catalyze the breakdown of ministering 5-FU has been suggested in Western countries (2- pyrimidine chemotherapy agents such as 5-fluorouracil, 6), but DPD deficiency has not been reported in Japan. may cause serious adverse reactions to these agents. We Using a method that permits analysis of dihydrouracil and attempted to establish the reference range for urinary pyri- uracil in small volumes of urine, we previously screened Japa- midines in adults to detect individuals with abnormal py- nese infants for abnormalities of pyrimidine metabolism and rimidine metabolism. -

Catabolism of Xanthine and Uracil in Tumor-Bearing Rats'1

Catabolism of Xanthine and Uracil in Tumor-bearing Rats'1 CHUNGWu ANDJEREM. BAUER (Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan) SUMMARY The urinary excretion of allantoin and uric acid was greatly increased in rats bear ing Walker carcinoma 256. The increase was greater with more advanced tumor growth. A similar increase was also observed in the allantoin concentration of the plasma and liver of these rats. An increase in the RNA and DNA content and a decrease in the RNA/DNA ratio were found in the muscle of the tumor-bearing animals. Liver xan- thine oxidase activity was increased in rats bearing Walker 256 and Guerin carcinomas and NovikofT and Morris 3683 hepatomas but was unchanged in rats bearing Jensen sarcoma, Morris 5123, and Morris 3924-A hepatomas, when compared with their re spective controls fed ad libitum. Liver uracil reductase activity showed a decrease in rats bearing Morris 5123 and Morris 3924-A hepatomas but no change in rats bearing Walker carcinoma 256 and Novikoff and Morris 3683 hepatomas. These findings indi cate that the effect of different tumors on a given enzyme in the host system need not be qualitatively uniform. Finally, unlike the other hepatomas tested, Morris 5123 hepatoma was found to possess xanthine oxidase activity approaching that found in a normal liver. That the growth of a malignant tumor causes tivity has not been studied in detail in tumor-bear many disturbances in the metabolism of the host ing rats. A survey of this enzyme activity in the is well known. -

Study of Nucleoside Degrading Enzyme Activities in Bean, Organic Bean, Okra, Organic Okra, Squash and Organic Squash

STUDY OF NUCLEOSIDE DEGRADING ENZYME ACTIVITIES IN BEAN, ORGANIC BEAN, OKRA, ORGANIC OKRA, SQUASH AND ORGANIC SQUASH by Shafiqa A. Alshaiban A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Chemistry Middle Tennessee State University August 2016 Thesis Committee: Dr. Paul C. Kline, Chair Dr. Andrew Burden Dr. Anthony Farone I dedicate this research to my parents, my sisters, and my brothers. I love you all. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to sincerely thank Dr. Paul Kline for the support and guidance he has offered throughout the entirety of the research and thesis writing process. I also wish to thank my committee members, Dr. Donald A. Burden and Dr. Anthony Farone for their advice and willingness to read my work. I would like to thank all the staff and faculty members for their valuable support. Finally, I would like to express my thanks to my family and my friends for their support and love. Special thanks to my loving parents, my brothers and my sisters for their prayer, concern and kind words over the years. iii ABSTRACT Pyrimidine and purine nucleotide metabolism are essential for development and growth of all organisms. Nucleoside degradation reactions have been found in virtually all organisms. Many enzymes are involved in the degradation and salvage of nucleotides, nucleobases and nucleosides. Deaminases contribute in interconversion of one nucleoside into another by removing amino groups from the base. Nucleoside hydrolase is a glycosidase that catalyzes the cleavage of the N-glycosidic bond in nucleosides to facilitate recycling of nucleobases. -

Nucleotides, Nucleic Acids: General Information About Structure, Functions and Metabolism

MINISTRY OF HEALTH OF UKRAINE ZAPORIZHZHIA STATE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY Biological Chemistry Department Nucleotides, Nucleic acids: General Information about Structure, Functions and Metabolism A manual for independent work at home and in class for students of second year study of international faculty Speciality “Medicine” Zaporizhzhia, 2016 1 UDC 577.1(075.8) BBC 28.902я73 N92 The manual was approved on the Central Methodological Council of ZSMU on «____» _______________2016, the protocol №________ Reviewers: Prykhodko O.B., Head of Medical Biology, Parasitology and Genetics Department of Zaporizhzhia State Medical University, doctor of biological science Voskoboynik O.Yu., associate professor of Organic and Bioorganic Chemistry Department of Zaporizhzhia State Medical University, PhD Editors: Dr. Hab., professor Aleksandrova K. V. PhD, assoc. professor Ivanchenko D. G. PhD, assoc. professor Krisanova N. V. Nucleotides, Nucleic acids : General Information about Structure, Functions and Metabolism : a manual for independent work at home and in class for students of second year study of international faculty, speciality ―Medicine‖/ ed. : K. V. Aleksandrova, D. G. Ivanchenko, N. V. Krisanova. – Zaporizhzhia : ZSMU, 2016.- 84 p. This manual is recommended to use for students of International Faculty (the second year of study) for independent work at home and in class. Нуклеотиди, нуклеїнові кислоти : загальне уявлення про структуру, функції та метаболізм : навч. посіб. для самостійної аудиторної та позааудиторної роботи студентів 2 курсу міжнар. ф-ту, спеціальність «Медицина» / ред.. : К. В. Александрова, Д. Г. Іванченко, Н. В. Крісанова. - Запоріжжя : ЗДМУ, 2016. – 84 с. UDC 577.1(075.8) BBC 28.902я73 ©Aleksandrova K.V., IvanchenkoD.G., Krisanova N.V., 2016 ©Zaporizhzhia State Medical University, 2016 2 INTRODUCTION A study of questions for this manual is the basis for learning of all metabolic pathways for nucleotides and nucleic acids. -

1 Synthesis of C-2 and C-6 Functionalized

1 SYNTHESIS OF C-2 AND C-6 FUNCTIONALIZED RIBOFURANOSYLPURINE ANALOGUES AS POTENTIAL ANTIVIRAL AGENTS TARGETING INHIBITION OF INOSINE MONOPHOSPHATE DEHYDROGENASE. by Eric Osei-Tutu Bonsu (Under the Direction of Vasu Nair) ABSTRACT IMPDH is a key enzyme in the de novo biosynthesis of purine nucleotides. It catalyzes the conversion of inosine monophosphate (IMP) to xanthosine monophosphate (XMP) using NAD as a cofactor. XMP is successively converted to deoxyguanosine triphosphate (substrate for DNA synthesis) by GMP synthetase, phosphorylating enzymes and ribonucleotide reductase. IMPDH exists in two isoforms, type I and type II. These isoforms have the same size and share 84% homology. The type I isoform is expressed in both normal and rapidly proliferating cells, whereas type II is preferentially upregulated in proliferating cells. Inhibition of IMPDH has anticancer, antiviral, antibacterial and immunosuppressive effects. Three inhibitors of IMPDH are currently in clinical use: ribavirin (a broad spectrum antiviral), mizoribine (immunosuppressant used in Japan) and mycophenolic mofetil (prodrug of mycophenolic acid, US approved immunosuppressant). None of these inhibitors possess significant selectivity against the type II isoform over the type I, hence there are severe side effects. The quest for specific isozyme inhibitors led to the discovery of the potential antiviral activity of certain C-2 functionalized hypoxanthine and C-2, C-6 modified purine systems against HSV1, HSV2, VV, VSV and RSV. 2 Nair and coworkers have synthesized similar congeners, including 2-vinylinosine (broad spectrum antiviral), which is active due to its C-2 vinyl moiety acting as a Michael Acceptor. This dissertation elucidates the design and synthesis of new Michael Acceptor-type nucleosides. -

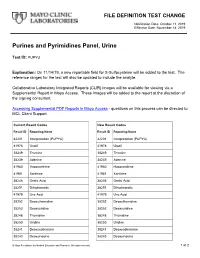

Purines and Pyrimidines Panel, Urine

FILE DEFINITION TEST CHANGE Notification Date: October 11, 2019 Effective Date: November 14, 2019 Purines and Pyrimidines Panel, Urine Test ID: PUPYU Explanation: On 11/14/19, a new reportable field for S-Sulfocysteine will be added to the test. The reference ranges for the test will also be updated to include the analyte. Collaborative Laboratory Integrated Reports (CLIR) images will be available for viewing via a Supplemental Report in Mayo Access. These images will be added to the report at the discretion of the signing consultant. Accessing Supplemental PDF Reports in Mayo Access - questions on this process can be directed to MCL Client Support. Current Result Codes New Result Codes Result ID Reporting Name Result ID Reporting Name 42201 Interpretation (PUPYU) 42201 Interpretation (PUPYU) 41978 Uracil 41978 Uracil 38249 Thymine 38249 Thymine 38239 Adenine 38239 Adenine 41980 Hypoxanthine 41980 Hypoxanthine 41981 Xanthine 41981 Xanthine 38246 Orotic Acid 38246 Orotic Acid 38251 Dihydroorotic 38251 Dihydroorotic 41979 Uric Acid 41979 Uric Acid 38252 Deoxythymidine 38252 Deoxythymidine 38253 Deoxyuridine 38253 Deoxyuridine 38248 Thymidine 38248 Thymidine 38250 Uridine 38250 Uridine 38241 Deoxyadenosine 38241 Deoxyadenosine 38243 Deoxyinosine 38243 Deoxyinosine © Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved. 1 of 2 38242 Deoxyguanosine 38242 Deoxyguanosine 38240 Adenosine 38240 Adenosine 38245 Inosine 38245 Inosine 38244 Guanosine 38244 Guanosine 38254 AICAR 38254 AICAR 38247 Succinyladenosine 38247 Succinyladenosine -

Enzymes of Uracil Catabolism in Normal and Neoplastic Human Tissues1 / Fardos N

[CANCER RESEARCH 45, 5405-5412, November 1985] Enzymes of Uracil Catabolism in Normal and Neoplastic Human Tissues1 / Fardos N. M. Naguib,2 Mahmoud H. el Kouni, and Sungman Cha Division of Biology and Medicine, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island 02912 ABSTRACT to homogeneity from rat liver cytosol (9). Dihydropyrimidinase (5,6-dihydropyrimidine amidohydrolase, Enzymes of the pyrimidine base catabolism, dihydrouracil de- EC 3.5.2.2) is the second enzyme of pyrimidine base degrada hydrogenase (EC 1.3.1.2), dihydropyrimidinase (EC 3.5.2.2), and tion. It is responsible for the reversible hydrolytic ring opening of /3-ureidopropionase (EC 3.5.1.6) were compared in the cytosolic dihydrouracil and dihydrothymine and is located in the cytosol extract of several normal and neoplastic human tissues. The fraction (12-15). activity was measured by following the catabolism of [6-14C]- /3-Ureidopropionase (A/-carbamoyl-j8-alanine amidohydrolase, uracil to dihydrouracil, carbamyl-/3-alanine, and /3-alanine. Sub EC 3.5.1.6) is the last of the pyrimidine degradative enzymes. It strate inhibition, hysteresis, allosterism, and the lack of dihydro splits the /3-ureidopropionic acid (carbamyl-ß-alanine) or /3-urei- pyrimidinase are pointed out as special problems in assaying doisobutyric acid formed by dihydropyrimidinase from dihydrour enzymes of pyrimidine degradation. The activity of dihydrouracil acil or dihydrothymine into 0-alanine or /9-aminoisobutyric acid, dehydrogenase has been demonstrated in several human extra- ammonia, and carbon dioxide (Chart 1). /3-Ureidopropionase is hepatic tissues and tumors. The enzyme is rate limiting in extra- also located in the cytosol (14, 16, 17).