Enbridge Northern Gateway Project Joint Review Panel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

RG 42 - Marine Branch

FINDING AID: 42-21 RECORD GROUP: RG 42 - Marine Branch SERIES: C-3 - Register of Wrecks and Casualties, Inland Waters DESCRIPTION: The finding aid is an incomplete list of Statement of Shipping Casualties Resulting in Total Loss. DATE: April 1998 LIST OF SHIPPING CASUALTIES RESULTING IN TOTAL LOSS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA COASTAL WATERS SINCE 1897 Port of Net Date Name of vessel Registry Register Nature of casualty O.N. Tonnage Place of casualty 18 9 7 Dec. - NAKUSP New Westminster, 831,83 Fire, B.C. Arrow Lake, B.C. 18 9 8 June ISKOOT Victoria, B.C. 356 Stranded, near Alaska July 1 MARQUIS OF DUFFERIN Vancouver, B.C. 629 Went to pieces while being towed, 4 miles off Carmanah Point, Vancouver Island, B.C. Sept.16 BARBARA BOSCOWITZ Victoria, B.C. 239 Stranded, Browning Island, Kitkatlah Inlet, B.C. Sept.27 PIONEER Victoria, B.C. 66 Missing, North Pacific Nov. 29 CITY OF AINSWORTH New Westminster, 193 Sprung a leak, B.C. Kootenay Lake, B.C. Nov. 29 STIRINE CHIEF Vancouver, B.C. Vessel parted her chains while being towed, Alaskan waters, North Pacific 18 9 9 Feb. 1 GREENWOOD Victoria, B.C. 89,77 Fire, laid up July 12 LOUISE Seaback, Wash. 167 Fire, Victoria Harbour, B.C. July 12 KATHLEEN Victoria, B.C. 590 Fire, Victoria Harbour, B.C. Sept.10 BON ACCORD New Westminster, 52 Fire, lying at wharf, B.C. New Westminster, B.C. Sept.10 GLADYS New Westminster, 211 Fire, lying at wharf, B.C. New Westminster, B.C. Sept.10 EDGAR New Westminster, 114 Fire, lying at wharf, B.C. -

Marine Recreation in the Desolation Sound Region of British Columbia

MARINE RECREATION IN THE DESOLATION SOUND REGION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA by William Harold Wolferstan B.Sc., University of British Columbia, 1964 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Geography @ WILLIAM HAROLD WOLFERSTAN 1971 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY December, 1971 Name : William Harold Wolf erstan Degree : Master of Arts Title of Thesis : Marine Recreation in the Desolation Sound Area of British Columbia Examining Committee : Chairman : Mar tin C . Kellman Frank F . Cunningham1 Senior Supervisor Robert Ahrens Director, Parks Planning Branch Department of Recreation and Conservation, British .Columbia ABSTRACT The increase of recreation boating along the British Columbia coast is straining the relationship between the boater and his environment. This thesis describes the nature of this increase, incorporating those qualities of the marine environment which either contribute to or detract from the recreational boating experience. A questionnaire was used to determine the interests and activities of boaters in the Desolation Sound region. From the responses, two major dichotomies became apparent: the relationship between the most frequented areas to those considered the most attractive and the desire for natural wilderness environments as opposed to artificial, service- facility ones. This thesis will also show that the most valued areas are those F- which are the least disturbed. Consequently, future planning must protect the natural environment. Any development, that fails to consider the long term interests of the boater and other resource users, should be curtailed in those areas of greatest recreation value. iii EASY WILDERNESS . Many of us wish we could do it, this 'retreat to nature'. -

New Available LNG Sites on Canada's West Coast

New Available LNG Sites on Canada’s West Coast Disclaimer This presentation contains information that is preliminary in nature and may be subject to change in the future. Forward looking statements involve risks and uncertainties because they relate to events and depend upon circumstances that will or may vary in the future. Actual outcomes may differ. Any party interested in pursuing the opportunities presented here should undertake its own research and due diligence to satisfy itself of the quality of the information presented within. 2 Contents Page Introduction 4 Welcome 5 The Nisga’a Nation – An Overview 6 Natural Gas Supply in Western Canada 11 Nisga’a Nation Sites for a Floating or Land-Based LNG Facility 15 Regional Infrastructure 28 Next Steps 37 Contacts 39 3 Introduction • The Nisga’a Nation wishes to attract sustainable economic development, including LNG projects, to our area. • Canada’s vast resources of natural gas are ideal as a new LNG supply source for global markets. • Suitable sites for LNG development along the west coast of Canada are limited due to the mountainous terrain and restricted access. • Some perceive that most, if not all, sites have already been selected by various parties for their LNG projects. • The Nisga’a Nation owns all or part of four first rate sites for development that have not previously been identified for LNG projects. • These sites offer unique opportunities as a result of the Nisga’a Treaty, our Nisga’a Government, our property interests and our unique environmental assessment rights. • This package is a preliminary description of available LNG sites on the Portland Inlet waterway, near the Nass River, on Canada’s west coast, north of Prince Rupert. -

The Boundary Reefs: Glass Sponge (Porifera: Hexactinellidae) Reefs on the International Border Between Canada and the United States

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-264 The Boundary Reefs: Glass Sponge (Porifera: Hexactinellidae) Reefs on the International Border Between Canada and the United States by R. P. Stone, K. W. Conway, D. J. Csepp, J. V. Barrie U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Alaska Fisheries Science Center January 2014 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS The National Marine Fisheries Service's Alaska Fisheries Science Center uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible. Documents within this series reflect sound professional work and may be referenced in the formal scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-AFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS-F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest Fisheries Center. The NMFS-NWFSC series is currently used by the Northwest Fisheries Science Center. This document should be cited as follows: Stone, R. P., K. W. Conway, D. J. Csepp, and J. V. Barrie. 2013. The boundary reefs: glass sponge (Porifera: Hexactinellida) reefs on the international border between Canada and the United States. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-264, 31 p. Document available: http://www.afsc.noaa.gov/Publications/AFSC-TM/NOAA-TM-AFSC-264.pdf Reference in this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-264 The Boundary Reefs: Glass Sponge (Porifera: Hexactinellidae) Reefs on the International Border Between Canada and the United States by R. -

111 �I �L 140419 6

rn N UFO Lb ary MPO Bib otheque 111 I l 140419 6 Pacific Region Chart Sales and Distribution Office 1990 VANCOUVER INTERNATIONAL BOAT SHOW REPORT March 1990 GV 775 B627 Feb90 ILI 31 7 ' 1990 VANCOUVER BOAT SHOW REPORT B.C. PLACE STADIUM, VANCOUVER, B.C. February 7-11, 1990 CHS Participants Chart Distribution/Amendments Chart Production Sailing Dioections D. Fisher W.S. Crowther G. Richardson J. Yee J. Sadlish D. Jodrell The Chart Amendment Section designed the display for this event. The seven panels focused on how symbols and abbreviations used on CHS charts related to the terminology used in Chart 1 and to the actual features in the field. Each panel consisted of a nautical chart with lines running from specific chart symbols to corresponding Chart 1 excerpts and colour photographs taken of the highlighted feature. This was the final year that CHS will sell charts and publications at Boat Shows. A letter will be sent to Pacific Region Chart Dealers advising them of this decision and encouraging them to sell CHS products at the 1991 Boat Show. Personnel were given an information sheet (copy attached) prior to the opening of the show which advised them which new charts were scheduled for printing in 1990 and information on chart pricing and the availability of Sailing Directions. Sales totalled $9.2K which included 556 charts and 241 publications. 1990 Radio Aids and List of Lights, Buoys and Fog Signals were not in stock at the time of the show. Boat Show statistics are attached as Appendix 2. Public reaction to not selling charts - negative. -

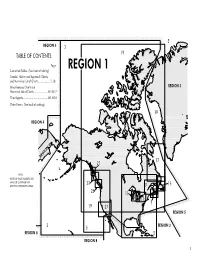

Index to NGA Charts, Region 1

1 2 REGION 1 COASTAL CHARTS Stock Number Title Scale =1: 11004 Mississippi River to Rio Grande 866,500 14003 Cape Race to Cape Henry 1,532,210 14018 The Grand Banks of Newfoundland and the Adjacent Coast 1,200,000 14024 Island of Newfoundland 720,240 15017 Hudson Strait (OMEGA) 1,000,000 15018 Belle Isle to Resolution Island (OMEGA) 1,000,000 15020 Hudson Strait to Greenland 1,501,493 15023 Queen Elizabeth Islands - Southern Part and Adjacent Waters 1,000,000 16220 St. Lawrence Island to Bering Strait 315,350 17003 Strait of Juan de Fuca to Dixon Entrance 1,250,000 18000 Point Conception to Isla Cedros 950,000 19008 Hawaiian Islands (OMEGA-BATHYMETRIC CHART) 1,030,000 38029 Baffin Bay (OMEGA) 917,000 38032 Godthabsfjord to Qeqertarsuaq including Cumberland Peninsula 841,000 38280 Kennedy Channel-Kane Basin to Hall Basin 300,000 38300 Smith Sound and Kane Basin 300,000 38320 Inglefield Bredning &Approaches 300,000 96028 Poluostrov Kamchatka to Aleutian Islands including Komandorskiye Ostrova 1,329,300 96036 Bering Strait (OMEGA) 928,770 3 4 REGION 1 COASTAL CHARTS EAST AND WEST COASTS-UNITED STATES Stock Number Title Scale =1: 11461 Straits of Florida-Southern Portion 300,000 13264 Approaches to Bay of Fundy 300,000 17005 Vancouver Island 525,000 17008 Queen Charlotte Sound to Dixon Entrance 525,000 17480 Queen Charlotte Sound 365,100 18766 San Diego to Islas De Todos Santos (LORAN-C) 180,000 5 6 NOVA SCOTIA AREA Stock Number Title Scale =1: Stock Number Title Scale =1: 14061 Grand Manan (Bay of Fundy) 60,000 14136 Sydney Harbour 20,000 14081 Medway Harbour to Lockeport Harbour including Liverpool 80,000 Plans: A. -

Lithodes Aequispina) and Their Infestation by a Rhizocephalan Barnacle Parasite (Briarosaccus Callosus)

223 DFO Lib ary MPO Bib iothèque Inn . 011111111i no 12021818 c Observations on Portland Inlet Syztem, Northern British Columbia Golden King Crabs (Lithodes aequispina) and Their Infestation by a Rhizocephalan Barnacle Parasite (Briarosaccus callosus) N. A. Sloan Department of Feries and Oceans Fisheries Research Branch LIERAk Pacific Biological Station Nanaimo, British Columbia V9R 51<.`>; • • Jen 24196 EIPUOTHÈJL July 1984 LCanadian Manuscript Rep _êrt of Fisheries and Aquatic Sf_ Jrices No. 1779 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences These reports contain scientific and technical information that represents an important contribution to existing knowledge but which for some reason may not be appropriate for primary scientific (i.e. Journal) publication. They differ from Tech- nical Reports in terms of subject scope and potential audience: Manusciipt Reports deal primarily with national or regional problems and distribution is generally restrict- ed to institutions or individuals located in particular regions of Canada. No restriction is placed on subject matter and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries management, technology and development, ocean sciences, and aquatic environments relevant to Canada. Manuscript Reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report will be abstracted by Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts and will be indexed annually in the Department's index to scientific and technical publications. Numbers 1-900 in this series were issued as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Biological Board of Canada, and subsequent to 1937 when the name of the Board was changed by Act of Parliament, as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. -

Pacific Fishery Management Areas and 2017/2018 Sea Cucumber Quota Management Area Maps – DRAFT

Appendix 10: Pacific Fishery Management Areas and 2017/2018 Sea Cucumber Quota Management Area Maps – DRAFT Harvesters are reminded that these maps and the area descriptions in Appendices 1 and 9 are to be used for reference only. The final authority of these descriptions of Areas, Subareas and portions thereof is as set out in the Pacific Fishery Management Area Regulations. More detailed maps and descriptions of Areas and Subareas are available on the Internet at: www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fm-gp/maps-cartes/areas-secteurs/index-eng.html Please note permanent area closures listed in Appendix 1, Section 5. Not all permanent area closures are illustrated on these maps. Cross-hatched/Stippled polygons represent Quota Management Areas (QMA), red polygons represent closure areas. Full QMA descriptions are listed in Appendix 9. Appendix 10: Pacific Fishery Management Areas and Sea Cucumber Quota Management Area Maps – 2017/2018 Page 1 of 20 Figure 1. QMA 3A Work Channel: Subarea 3-6; QMA 3B Portland Inlet: Subarea 3-7; QMA 3C Steamer Pass: Subareas 3-8 and 3- 10; QMA 3D Pearse Canal: Subarea 3-3 and portion of 3-11 (excluding Winter Inlet); Nasoga Gulf CNTR: Subarea 3-9.See section 5 in Appendix 1 for a full description of all closures. Appendix 10: Pacific Fishery Management Areas and Sea Cucumber Quota Management Area Maps – 2017/2018 Page 2 of 20 Figure 2. QMA 4A West Dundas Group: Subareas 3-1 and 4-1 ; QMA 4B East Dundas Group: Portion of Subarea 4-5. Appendix 10: Pacific Fishery Management Areas and Sea Cucumber Quota Management Area Maps – 2017/2018 Page 3 of 20 Figure 3. -

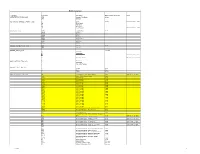

Code Search Results

ECAS Code List Code Table Code Value Description Where Used in Application Notes ADS_INSECT_SPECIES_CODE MPB Mountain Pine Beetle Interior UNK Unknown ADS_SPECIES_DAMAGE_CATGRY_CODE G Green Interior Expires on Dec 1, 2007 GA Green Attack RA Red Attack YA Gray Attack DP Dead Potential Expires on Dec 1, 2007 Ads_Location_Code CARV Campbell River Coast CHWK Chilliwack HOUS Houston MERR Merritt NANA Nanaimo PRRU Prince Rupert TERR Terrace VANC Vancouver VICT Victoria Appraisal_Amendment_Type_Code ADD Addition Coast DEL Deletion Appraisal_Category_Code Common N Initial ADS R Reappraisal D Redetermination Expires on Aug 1, 2013 P Post-Harvest ADS Effective on Apr 1, 2019 Apprsl_Certification_Type_Code R Reviewed Common S Supervised P Personally Prepared Appraisal_Culvert_Type_Code W Wooden Coast M Metal Coast T Tabular Interior Appraisal_Document_Type_Code BR Detailed Engineering - Bridge Repairs Coast Expired Dec 15, 2019 CAF Cruise - Cruise Analysis Form Coast CEF1 NDC Form #1 Coast CEF2 NDC Form #2 Coast CEF3 NDC Form #3 Coast CEF4 NDC Form #4 Coast CEF5 NDC Form #5 Coast CEF6 NDC Form #6 Coast CEF7 NDC Form #7 Coast CEF8 NDC Form #8 Coast CEF9 NDC Form #9 Coast CEF10 NDC Form #10 Coast CEF11 NDC Form #11 Coast CEF12 NDC Form #12 Coast CEF13 NDC Form #13 Coast CEF14 NDC Form #14 Coast CEF15 NDC Form #15 Coast CEF16 NDC Form #16 Coast CEF17 NDC Form #17 Coast CEF18 NDC Form #18 Coast CEF19 NDC Form #19 Coast CEF20 NDC Form #20 Coast SOFZ Specified Operations - Fibre Recovery Zone Coast SOMS Specified Operations - Miscellaneous Coast DCDA -

Chapter 4 Seasonal Weather and Local Effects

BC-E 11/12/05 11:28 PM Page 75 LAKP-British Columbia 75 Chapter 4 Seasonal Weather and Local Effects Introduction 10,000 FT 7000 FT 5000 FT 3000 FT 2000 FT 1500 FT 1000 FT WATSON LAKE 600 FT 300 FT DEASE LAKE 0 SEA LEVEL FORT NELSON WARE INGENIKA MASSET PRINCE RUPERT TERRACE SANDSPIT SMITHERS FORT ST JOHN MACKENZIE BELLA BELLA PRINCE GEORGE PORT HARDY PUNTZI MOUNTAIN WILLAMS LAKE VALEMOUNT CAMPBELL RIVER COMOX TOFINO KAMLOOPS GOLDEN LYTTON NANAIMO VERNON KELOWNA FAIRMONT VICTORIA PENTICTON CASTLEGAR CRANBROOK Map 4-1 - Topography of GFACN31 Domain This chapter is devoted to local weather hazards and effects observed in the GFACN31 area of responsibility. After extensive discussions with weather forecasters, FSS personnel, pilots and dispatchers, the most common and verifiable hazards are listed. BC-E 11/12/05 11:28 PM Page 76 76 CHAPTER FOUR Most weather hazards are described in symbols on the many maps along with a brief textual description located beneath it. In other cases, the weather phenomena are better described in words. Table 3 (page 74 and 207) provides a legend for the various symbols used throughout the local weather sections. South Coast 10,000 FT 7000 FT 5000 FT 3000 FT PORT HARDY 2000 FT 1500 FT 1000 FT 600 FT 300 FT 0 SEA LEVEL CAMPBELL RIVER COMOX PEMBERTON TOFINO VANCOUVER HOPE NANAIMO ABBOTSFORD VICTORIA Map 4-2 - South Coast For most of the year, the winds over the South Coast of BC are predominately from the southwest to west. During the summer, however, the Pacific High builds north- ward over the offshore waters altering the winds to more of a north to northwest flow. -

Fjords! (Especially the Kitimat Fjord System)

Bangarang February 2014 Backgrounder1 Fjords! (especially the Kitimat Fjord System) Eric Keen Abstract Fjords are awesome, and sometimes there are whales in them. This raises some questions: First of all, where do fjord babies come from? (Some Great Ice Cream Scoop in the Sky???) Why should we care about them? (Where to begin?) Where in the world do they happen? (A Goldilocks temperate zone and it’s perty too!) Why are British Columbia’s fjords the best? (If you’ve ever visited them you wouldn’t be asking such stupid questions.) What do you know about the fjords of the Gitga’at Territory and the Bangarang study area? (Ah, the Kitimat Fjord System! Where to begin?!) Contents Introduction Defined Worldwide British Columbia The Kitimat Fjord System Physical-Chemical Oceanography Freshwater Input Circulation Estuarine Wind-Driven Tidal Features Property Distribution Vertical Structure Horizontal Structure Seasonality Other Properties (pH, DO, nutrients) Deep & Bottom Waters Sediments Literature Cited 1 Bangarang Backgrounders are imperfect but rigorous reviews – written in haste, not peer-reviewed – in an effort to organize and memorize the key information for every aspect of the project. They will be updated regularly as new learnin’ is incorporated. 1 Introduction Due to the complexity of their ecological space, coastal waters comprise some of the most diverse and productive marine habitats on earth (Levin & Dayton 2009). This high biodiversity is the cornerstone of lucrative fisheries, tourism industries, and innumerable ecosystem services, including nutrient cycling, nursery habitat, food web support, carbon sequestration, and tourism revenue (Turner 2000). And yet, while the health of coastal waters is the most economically valuable and easily monitored of marine systems, they are also among the most endangered (Gray 1997).