The Equestrian Portrait of Alexander the Great on a New Tetradrachm of Seleucus I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics Title The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xh6g8nn Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics, 2(1) ISSN 2373-7115 Author Gavryushkina, Marina Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gavryushkina 1 The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013 Abstract: Hellenistic coinage is a popular topic in art historical research as it is an invaluable resource of information about the political relationship between Greek rulers and their subjects. However, most scholars have focused on the wealthier and more famous dynasties of the Ptolemies and the Seleucids. Thus, there have been considerably fewer studies done on the artistic styles of the coins of the smaller outlying Hellenistic kingdoms. This paper analyzes the numismatic portraiture of the kings of Pontus, a peripheral kingdom located in northern Anatolia along the shores of the Black Sea. In order to evaluate the degree of similarity or difference in the Pontic kings’ modes of representation in relation to the traditional royal Hellenistic style, their coinage is compared to the numismatic depictions of Alexander the Great of Macedon. A careful art historical analysis reveals that Pontic portrait styles correlate with the individual political motivations and historical circumstances of each king. Pontic rulers actively choose to diverge from or emulate the royal Hellenistic portrait style with the intention of either gaining support from their Anatolian and Persian subjects or being accepted as legitimate Greek sovereigns within the context of international politics. -

Seleucid Coinage and the Legend of the Horned Bucephalas

Seleucid coinage and the legend of the horned Bucephalas Autor(en): Miller, Richard P. / Walters, Kenneth R. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische numismatische Rundschau = Revue suisse de numismatique = Rivista svizzera di numismatica Band (Jahr): 83 (2004) PDF erstellt am: 04.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-175883 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch RICHARD P. MILLER AND KENNETH R.WALTERS SELEUCID COINAGE AND THE LEGEND OF THE HORNED BUCEPHALAS* Plate 8 [21] Balaxian est provincia quedam, gentes cuius Macometi legem observant et per se loquelam habent. Magnum quidem regnum est. Per successionem hereditariam regitur, quae progenies a rege Alexandra descendit et a filia regis Darii Magni Persarum... -

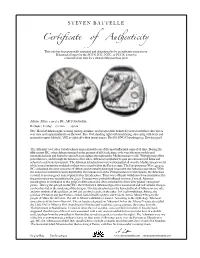

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

The Coinage of Akragas C

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Numismatica Upsaliensia 6:1 STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA 6:1 The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC Text and Plates ULLA WESTERMARK I STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA Editors: Harald Nilsson, Hendrik Mäkeler and Ragnar Hedlund 1. Uppsala University Coin Cabinet. Anglo-Saxon and later British Coins. By Elsa Lindberger. 2006. 2. Münzkabinett der Universität Uppsala. Deutsche Münzen der Wikingerzeit sowie des hohen und späten Mittelalters. By Peter Berghaus and Hendrik Mäkeler. 2006. 3. Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. Svenska vikingatida och medeltida mynt präglade på fastlandet. By Jonas Rundberg and Kjell Holmberg. 2008. 4. Opus mixtum. Uppsatser kring Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. 2009. 5. ”…achieved nothing worthy of memory”. Coinage and authority in the Roman empire c. AD 260–295. By Ragnar Hedlund. 2008. 6:1–2. The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC. By Ulla Westermark. 2018 7. Musik på medaljer, mynt och jetonger i Nils Uno Fornanders samling. By Eva Wiséhn. 2015. 8. Erik Wallers samling av medicinhistoriska medaljer. By Harald Nilsson. 2013. © Ulla Westermark, 2018 Database right Uppsala University ISSN 1652-7232 ISBN 978-91-513-0269-0 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876 (http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876) Typeset in Times New Roman by Elin Klingstedt and Magnus Wijk, Uppsala Printed in Sweden on acid-free paper by DanagårdLiTHO AB, Ödeshög 2018 Distributor: Uppsala University Library, Box 510, SE-751 20 Uppsala www.uu.se, [email protected] The publication of this volume has been assisted by generous grants from Uppsala University, Uppsala Sven Svenssons stiftelse för numismatik, Stockholm Gunnar Ekströms stiftelse för numismatisk forskning, Stockholm Faith and Fred Sandstrom, Haverford, PA, USA CONTENTS FOREWORDS ......................................................................................... -

Alexander's Empire

4 Alexander’s Empire MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES EMPIRE BUILDING Alexander the Alexander’s empire extended • Philip II •Alexander Great conquered Persia and Egypt across an area that today consists •Macedonia the Great and extended his empire to the of many nations and diverse • Darius III Indus River in northwest India. cultures. SETTING THE STAGE The Peloponnesian War severely weakened several Greek city-states. This caused a rapid decline in their military and economic power. In the nearby kingdom of Macedonia, King Philip II took note. Philip dreamed of taking control of Greece and then moving against Persia to seize its vast wealth. Philip also hoped to avenge the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 B.C. TAKING NOTES Philip Builds Macedonian Power Outlining Use an outline to organize main ideas The kingdom of Macedonia, located just north of Greece, about the growth of had rough terrain and a cold climate. The Macedonians were Alexander's empire. a hardy people who lived in mountain villages rather than city-states. Most Macedonian nobles thought of themselves Alexander's Empire as Greeks. The Greeks, however, looked down on the I. Philip Builds Macedonian Power Macedonians as uncivilized foreigners who had no great A. philosophers, sculptors, or writers. The Macedonians did have one very B. important resource—their shrewd and fearless kings. II. Alexander Conquers Persia Philip’s Army In 359 B.C., Philip II became king of Macedonia. Though only 23 years old, he quickly proved to be a brilliant general and a ruthless politician. Philip transformed the rugged peasants under his command into a well-trained professional army. -

Art and Royalty in Sparta of the 3Rd Century B.C

HESPERIA 75 (2006) ART AND ROYALTY Pages 203?217 IN SPARTA OF THE 3RD CENTURY B.C. ABSTRACT a The aim of this paper is to demonstrate that revival of the arts in Sparta b.c. was during the 3rd century owed mainly to royal patronage, and that it was inspired by Alexander s successors, the Seleukids and the Ptolemies in particular. The tumultuous transition from the traditional Spartan dyarchy to a and to its dominance Hellenistic-style monarchy, Sparta's attempts regain in the P?loponn?se (lost since the battle of Leuktra in 371 b.c.), are reflected in the of the hero Herakles as a role model promotion pan-Peloponnesian at for the single king the expense of the Dioskouroi, who symbolized dual a kingship and had limited, regional appeal. INTRODUCTION was Spartan influence in the P?loponn?se dramatically reduced after the battle of Leuktra in 371 b.c.1 The history of Sparta in the 3rd century b.c. to ismarked by intermittent efforts reassert Lakedaimonian hegemony.2 A as a means to tendency toward absolutism that end intensified the latent power struggle between the Agiad and Eurypontid royal houses, leading to the virtual abolition of the traditional dyarchy in the reign of the Agiad Kleomenes III (ca. 235-222 b.c.), who appointed his brother Eukleides 1. For the battle of Leuktra and its am to and Ellen Millen 2005.1 grateful Graham Shipley Paul Cartledge and see me to am consequences, Cartledge 2002, and Ellen Millender for inviting der for historical advice. I also 251-259. -

NW-49 Final FSR Jhelum Report

FEASIBILITY REPORT ON DETAILED HYDROGRAPHIC SURVEY IN JHELUM RIVER (110.27 KM) FROM WULAR LAKE TO DANGPORA VILLAGE (REGION-I, NW- 49) Submitted To INLAND WATERWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA A-13, Sector-1, NOIDA DIST-Gautam Buddha Nagar UTTAR PRADESH PIN- 201 301(UP) Email: [email protected] Web: www.iwai.nic.in Submitted By TOJO VIKAS INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD Plot No.4, 1st Floor, Mehrauli Road New Delhi-110074, Tel: +91-11-46739200/217 Fax: +91-11-26852633 Email: [email protected] Web: www.tojovikas.com VOLUME – I MAIN REPORT First Survey: 9 Jan to 5 May 2017 Revised Survey: 2 Dec 2017 to 25 Dec 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Tojo Vikas International Pvt. Ltd. (TVIPL) express their gratitude to Mrs. Nutan Guha Biswas, IAS, Chairperson, for sparing their valuable time and guidance for completing this Project of "Detailed Hydrographic Survey in Ravi River." We would also like to thanks Shri Pravir Pandey, Vice-Chairman (IA&AS), Shri Alok Ranjan, Member (Finance) and Shri S.K.Gangwar, Member (Technical). TVIPL would also like to thank Irrigation & Flood control Department of Srinagar for providing the data utilised in this report. TVIPL wishes to express their gratitude to Shri S.V.K. Reddy Chief Engineer-I, Cdr. P.K. Srivastava, Ex-Hydrographic Chief, IWAI for his guidance and inspiration for this project. We would also like to thank Shri Rajiv Singhal, A.H.S. for invaluable support and suggestions provided throughout the survey period. TVIPL is pleased to place on record their sincere thanks to other staff and officers of IWAI for their excellent support and co-operation through out the survey period. -

Cult Statue of a Goddess

On July 31, 2007, the Italian Ministry of Culture and the Getty Trust reached an agreement to return forty objects from the Museum’s antiq uities collection to Italy. Among these is the Cult Statue of a Goddess. This agreement was formally signed in Rome on September 25, 2007. Under the terms of the agreement, the statue will remain on view at the Getty Villa until the end of 2010. Cult Statue of a Goddess Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at The Getty Villa May 9, 2007 i © 2007 The J. Paul Getty Trust Published on www.getty.edu in 2007 by The J. Paul Getty Museum Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 900491682 www.getty.edu Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Benedicte Gilman, Editor Diane Franco, Typography ISBN 9780892369287 This publication may be downloaded and printed in its entirety. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for noncommercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors. For any other uses, please refer to the J. Paul Getty Trust’s Terms of Use. ii Cult Statue of a Goddess Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at the Getty Villa, May 9, 2007 Schedule of Proceedings iii Introduction, Michael Brand 1 Acrolithic and Pseudoacrolithic Sculpture in Archaic and Classical Greece and the Provenance of the Getty Goddess Clemente Marconi 4 Observations on the Cult Statue Malcolm Bell, III 14 Petrographic and Micropalaeontological Data in Support of a Sicilian Origin for the Statue of Aphrodite Rosario Alaimo, Renato Giarrusso, Giuseppe Montana, and Patrick Quinn 23 Soil Residues Survey for the Getty Acrolithic Cult Statue of a Goddess John Twilley 29 Preliminary Pollen Analysis of a Soil Associated with the Cult Statue of a Goddess Pamela I. -

An Examination of the Political Philosophy of Plutarch's Alexander

“If I were not Alexander…” An Examination of the Political Philosophy of Plutarch’s Alexander- Caesar Richard Buckley-Gorman A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Classics 2016 School of Art History, Classics and Religious Studies 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………………3 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Chapter One: Plutarch’s Methodology…………………………………………………………….8 Chapter Two: The Alexander………………………………………………………………………….18 Chapter Three: Alexander and Caesar……………………………………………………………47 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………………….71 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………………….73 2 | P a g e Acknowledgements Firstly and foremost to my supervisor Jeff Tatum, for his guidance and patience. Secondly to my office mates James, Julia, Laura, Nikki, and Tim who helped me when I needed it and made research and writing more fun and less productive than it would otherwise have been. I would also like to thank my parents, Sue and Phil, for their continuous support. 3 | P a g e Abstract This thesis examines Plutarch’s Alexander-Caesar. Plutarch’s depiction of Alexander has been long recognised as encompassing many defects, including an overactive thumos and a decline in character as the narrative progresses. In this thesis I examine the way in which Plutarch depicts Alexander’s degeneration, and argue that the defects of Alexander form a discussion on the ethics of kingship. I then examine the implications of pairing the Alexander with the Caesar; I examine how some of the themes of the Alexander are reflected in the Caesar. I argue that the status of Caesar as both a figure from the Republican past and the man who established the Empire gave the pair a unique immediacy to Plutarch’s time. -

A Collection of Exceptional Ancient Greek Coins

A Collection of Exceptional Ancient Greek Coins To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Book Room 34-35 New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Monday 24 October 2011 at 11.00 am Public viewing: Morton & Eden, 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Thursday 20 October 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Friday 21 October 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Sunday 23 October 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 51 Price £15 Enquiries: Tom Eden or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 160 (front); Lot 166 (back); Lot 126 (inside front and back covers) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Online Bidding Morton & Eden Ltd offer an online bidding service via www.the-saleroom.com. This is provided on the understanding that Morton & Eden Ltd shall not be responsible for errors or failures to execute internet bids for reasons including but not limited to: i) a loss of internet connection by either party; ii) a breakdown or other problems with the online bidding software; iii) a breakdown or other problems with your computer, system or internet connection. -

Chapter 8 Antiochus I, Antiochus IV And

Dodd, Rebecca (2009) Coinage and conflict: the manipulation of Seleucid political imagery. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/938/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Coinage and Conflict: The Manipulation of Seleucid Political Imagery Rebecca Dodd University of Glasgow Department of Classics Degree of PhD Table of Contents Abstract Introduction………………………………………………………………….………..…4 Chapter 1 Civic Autonomy and the Seleucid Kings: The Numismatic Evidence ………14 Chapter 2 Alexander’s Influence on Seleucid Portraiture ……………………………...49 Chapter 3 Warfare and Seleucid Coinage ………………………………………...…….57 Chapter 4 Coinages of the Seleucid Usurpers …………………………………...……..65 Chapter 5 Variation in Seleucid Portraiture: Politics, War, Usurpation, and Local Autonomy ………………………………………………………………………….……121 Chapter 6 Parthians, Apotheosis and political unrest: the beards of Seleucus II and Demetrius II ……………………………………………………………………….……131 Chapter 7 Antiochus III and Antiochus