Independent Schools in Singapore: Implications for Social and Educational Inequalities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

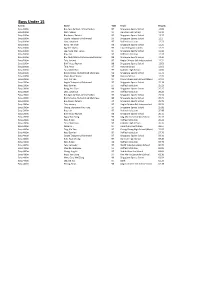

Boys Under 15

Boys Under 15 Events Name YOB Team Results Boys 100m Bin Agos Sahbali, Amirul Sofian 97 Singapore Sports School 12.09 Boys 100m Moh, Shaun 97 Dunman High School 12.11 Boys 100m Bin Anuar, Zuhairi 97 Singapore Sports School 12.17 Boys 100m Sugita Tadayoshi, Richmond 97 Singapore Sports School 12.2 Boys 100m Lew, Jonathon 97 Raffles Institution 12.23 Boys 100m Kang, Yee Cher 98 Singapore Sports School 12.25 Boys 100m Ng, Kee Hsien 97 Hwa Chong Institution 12.25 Boys 100m Lee, Song Wei, Lucas 97 Singapore Sports School 12.36 Boys 100m Poy, Ian 97 Raffles Institution 12.37 Boys 100m Bin Abdul Wahid, Muhammad Syazani 98 Singapore Sports School 12.44 Boys 100m Toh, Jeremy 97 Anglo Chinese Sch Independant 12.51 Boys 100m Bin Fairuz, Rayhan 98 Singapore Sports School 12.63 Boys 100m Thia, Aven 97 Victoria School 12.63 Boys 100m Tan, Chin Kean 97 Catholic High School 12.66 Boys 100m Bin Norzaha, Muhammad Shahrieza 98 Singapore Sports School 12.72 Boys 100m Chen, Ryan Shane 98 Victoria School 12.73 Boys 200m Ong, Xin Yao 97 Chung Cheng High School (Main) 24.91 Boys 200m Sugita Tadayoshi, Richmond 97 Singapore Sports School 25.18 Boys 200m Kee, Damien 97 Raffles Institution 25.23 Boys 200m Kang, Yee Cher 98 Singapore Sports School 25.25 Boys 200m Lew, Jonathon 97 Raffles Institution 25.26 Boys 200m Bin Agos Sahbali, Amirul Sofian 97 Singapore Sports School 25.50 Boys 200m Bin Norzaha, Muhammad Shahrieza 98 Singapore Sports School 25.71 Boys 200m Bin Anuar, Zuhairi 97 Singapore Sports School 25.72 Boys 200m Toh, Jeremy 97 Anglo Chinese Sch Independant -

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and Post-Colonial Singapore Reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus

From Orphanage to Entertainment Venue: Colonial and post-colonial Singapore reflected in the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus by Sandra Hudd, B.A., B. Soc. Admin. School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, September 2015 ii Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the Universityor any other institution, except by way of backgroundi nformationand duly acknowledged in the thesis, andto the best ofmy knowledgea nd beliefno material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text oft he thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. �s &>-pt· � r � 111 Authority of Access This thesis is not to be made available for loan or copying fortwo years followingthe date this statement was signed. Following that time the thesis may be made available forloan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. :3 £.12_pt- l� �-- IV Abstract By tracing the transformation of the site of the former Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, this thesis connects key issues and developments in the history of colonial and postcolonial Singapore. The convent, established in 1854 in central Singapore, is now the ‗premier lifestyle destination‘, CHIJMES. I show that the Sisters were early providers of social services and girls‘ education, with an orphanage, women‘s refuge and schools for girls. They survived the turbulent years of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore and adapted to the priorities of the new government after independence, expanding to become the largest cloistered convent in Southeast Asia. -

Dunman High School 德明政府中学 Dunman High School • 德明政府中学 02 Joint Admissions Exercise

DUNMAN HIGH SCHOOL 德明政府中学 DUNMAN HIGH SCHOOL • 德明政府中学 02 JOINT ADMISSIONS EXERCISE SCHOOL PHILOSOPHY VISION The premier school of Leaders of Honour MISSION To nurture our students to Care, to Serve, and to Lead MOTTO Honesty, Trustworthiness, Moral Courage, Loyalty DUNMAN HIGH SCHOOL • 德明政府中学 JOINT ADMISSIONS EXERCISE 03 DUNMANIAN OUTCOMES MORAL INTEGRITY Students are guided by honesty, trustworthiness, moral courage and loyalty. PASSION FOR LIFE & LEARNING Students are always learning and striving to be their best. IDEALISM Students have the conviction to make a difference to the world. 21ST CENTURY COMPETENCIES Students are proficient in critical and creative thinking, communication and information skills. BILINGUALISM & MULTICULTURALISM Students are effectively bilingual in English and Chinese, appreciate different cultures and navigate them with ease. ACTIVE CITIZENRY Students are global citizens rooted in Singapore who serve the community, both local and beyond. DUNMAN HIGH SCHOOL • 德明政府中学 04 JOINT ADMISSIONS EXERCISE CONTENTS 05 Principal’s Foreword 14 Senior High Co-Curriculum 06 What is the Dunmanian Edge? 16 Academic Achievements 07 Dunman High School in the 17 Careers, Scholarships and Words of Dunmanians: Higher Education Past, Present and Future 18 Your Future Beyond 08 Dunmanians Around the World Dunman High 10 Senior High Curriculum DUNMAN HIGH SCHOOL • 德明政府中学 JOINT ADMISSIONS EXERCISE 05 PRINCIPAL’S FOREWORD “The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character — that is the goal of true education.” – Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Dr. King’s vision about the goal of education is and a CCA Leader, embodying our school’s most relevant in today’s world where solutions mission – “To Care, To Serve, and To Lead”. -

A*Star Talent Search and Singapore Science & Engineering Fair 2020 Contents

A*STAR TALENT SEARCH AND SINGAPORE SCIENCE & ENGINEERING FAIR 2020 CONTENTS 03 Singapore Science & Engineering Fair (SSEF) 05 Foreword by Mdm Lee Lin Yee Chairperson, Singapore Science & Engineering Fair 2020 Working Committee 07 Singapore Science & Engineering Fair (SSEF) 2020 Winners 33 A*STAR Talent Search (ATS) 35 Foreword by Prof Ho Teck Hua Chairperson, A*STAR Talent Search 2020 Awards Committee 37 A*STAR Talent Search (ATS) 2020 Finalists 45 Acknowledgements 47 A*STAR Talent Search and Singapore Science & Engineering Fair 2020 Participants SINGAPORE SCIENCE & ENGINEERING FAIR BACKGROUND SSEF 2020 The Singapore Science & Engineering Fair (SSEF) is a national 592 projects were registered online for the SSEF this year. Of these, competition organised by the Ministry of Education (MOE), 320 were shortlisted for judging in March 2020. The total number of the Agency for Science, Technology & Research (A*STAR) and awards for the Main Category was 117, comprising 27 Gold, 22 Silver, Science Centre Singapore. The SSEF is affiliated to the highly 33 Bronze and 35 Merit awards. Additionally, 47 projects were also prestigious Regeneron International Science and Engineering awarded Special Awards sponsored by six different organisations Fair (Regeneron ISEF), which is regarded as the Olympics of (Institution of Chemical Engineers Singapore, Singapore University science competitions. of Technology and Design, Singapore Society for Microbiology and Biotechnology, Yale-NUS College, The Electrochemical Society, and SSEF is open to all secondary and pre-university students Singapore Association for the Advancement of Science). between 15 and 20 years of age. Participants submit research projects on science and engineering. In the Junior Scientists Category (for students under 15 years of age), 49 projects were shortlisted at the SSEF this year. -

62Nd SAA Cross Country Championships 2013 - Boys U15

62nd SAA Cross Country Championships 2013 - Boys U15 Position Number Bib Min Sec Name Team School/ Club Points 1 36 18 51 Louis Shia Wei Jie Individual North Vista Secondary School 1 2 3 19 04 Issac Tan ACS Team 1 Anglo-Chinese School (Independent) 2 3 56 19 12 Aaron Shane Tan Individual Singapore Sports School 3 4 57 19 31 Ierhan Muhd Raushan Individual Singapore Sports School 4 5 16 19 42 Shail Modi Individual Fabian William Coaching Concepts 5 6 8 19 43 Isaiah Boh Yu-Teng CHS Team 1 Catholic High School 6 7 39 19 45 Aaron Chan RI 'A' Raffles Institution 7 8 10 20 10 Ezra Goh Si Qi CHS Team 2 Catholic High School 8 9 42 20 27 Tan Ashton RI 'A' Raffles Institution 9 10 43 20 36 Cheong Wei Soon RI 'B' Raffles Institution 10 11 7 20 51 Dylan Tay CHS Team 1 Catholic High School 11 12 41 20 54 Koh Andy RI 'A' Raffles Institution 12 13 62 20 56 Keith Tan VS Team A Victoria School 13 14 32 21 00 Marcus Ong Nan Hua High C Men Team 1 Nan Hua High School 14 15 9 21 08 Vincent Chua Yao Sen CHS Team 1 Catholic High School 15 16 61 21 10 Jared Ng Yu Jie VS Team A Victoria School 16 17 4 21 11 Neil Kok ACS Team 1 Anglo-Chinese School (Independent) 17 18 63 21 19 Rohin Singh VS Team A Victoria School 18 19 60 21 22 Gabriel Neo VS Team A Victoria School 19 20 64 21 24 Kum Kai Weng VS Team B Victoria School 20 21 44 21 38 Dryton Teo RI 'B' Raffles Institution 21 22 25 21 46 Russell james Foo MSHS Team 1 Maris Stella High School 22 23 40 21 52 Chadalavada Abhijit RI 'A' Raffles Institution 23 24 2 22 00 Habib Nur S/O Basheer ACS Team 1 Anglo-Chinese -

Autonomy and Accountability in Victorian Schools

Making the Grade: Autonomy and Accountability in Victorian Schools Inquiry into School Devolution and Accountability Final Report July 2013 © State of Victoria 2013 This final report is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), without prior written permission from the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission. Cover images reproduced courtesy of the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development ISBN 978-1-922222-08-4 (print) ISBN 978-1-922222-09-1 (pdf) Disclaimer The views expressed herein are those of the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission and do not purport to represent the position of the Victorian Government. The content of this final report is provided for information purposes only. Neither the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission nor the Victorian Government accepts any liability to any person for the information (or the use of such information) which is provided in this final report or incorporated into it by reference. The information in this final report is provided on the basis that all persons having access to this final report undertake responsibility for assessing the relevance and accuracy of its content. Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission GPO Box 4379 MELBOURNE VICTORIA 3001 AUSTRALIA Telephone: (03) 9092 5800 Facsimile: (03) 9092 5845 Website: www.vcec.vic.gov.au An appropriate citation for this publication is: Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission 2013, Making the Grade: Autonomy and Accountability in Victorian Schools, Inquiry into School Devolution and Accountability, final report, July. About the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission The Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission (VCEC), which is supported by a secretariat, provides the Victorian Government with independent advice on business regulation reform and opportunities for improving Victoria’s competitive position. -

SECONDARY SCHOOL EDUCATION Shaping the Next Phase of Your Child’S Learning Journey 01 SINGAPORE’S EDUCATION SYSTEM : an OVERVIEW

SECONDARY SCHOOL EDUCATION Shaping the Next Phase of Your Child’s Learning Journey 01 SINGAPORE’S EDUCATION SYSTEM : AN OVERVIEW 03 LEARNING TAILORED TO DIFFERENT ABILITIES 04 EXPANDING YOUR CHILD’S DEVELOPMENT 06 MAXIMISING YOUR CHILD’S POTENTIAL 10 CATERING TO INTERESTS AND ALL-ROUNDEDNESS 21 EDUSAVE SCHOLARSHIPS & AWARDS AND FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE SCHEMES 23 CHOOSING A SECONDARY SCHOOL 24 SECONDARY 1 POSTING 27 CHOOSING A SCHOOL : PRINCIPALS’ PERSPECTIVES The Ministry of Education formulates and implements policies on education structure, curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. We oversee the development and management of Government-funded schools, the Institute of Technical Education, polytechnics and autonomous universities. We also fund academic research. SECONDARY SCHOOL 01 EDUCATION 02 Our education system offers many choices Singapore’s Education System : An Overview for the next phase of learning for your child. Its diverse education pathways aim to develop each child to his full potential. PRIMARY SECONDARY POST-SECONDARY WORK 6 years 4-5 years 1-6 years ALTERNATIVE SPECIAL EDUCATION SCHOOLS QUALIFICATIONS*** Different Pathways to Work and Life INTEGRATED PROGRAMME 4-6 Years ALTERNATIVE UNIVERSITIES QUALIFICATIONS*** SPECIALISED INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS** 4-6 Years WORK PRIVATELY FUNDED SCHOOLS SPECIAL 4-6 Years EDUCATION PRIMARY SCHOOL LEAVING EXPRESS GCE O-LEVEL JUNIOR COLLEGES/ GCE A-LEVEL CONTINUING EDUCATION EXAMINATION (PSLE) 4 Years CENTRALISED AND TRAINING (CET)**** INSTITUTE 2-3 Years Specialised Schools offer customised programmes -

Fellow Victorians Ladies and Gentlemen, Good Evening, Since

Fellow Victorians Ladies and Gentlemen, Good Evening, Since we are among friends, I hope that you will forgive me if I do not begin by recognising all the persons who should be recognised. It is many years since I last attended an Old Victorian’s dinner. So it is good to come again and see how many of my generation are here. A gathering of alumni from a secondary school is rather unusual. If you get to my age, in the seventies, you ask yourself what is so special about the very few years, not exceeding 5 years of your life that you spend in a secondary school or junior college. What kind of person you are today have been more shaped and influenced by your years after secondary school, either in further studies or in your livelihood or in your responsibility as spouse or parent or grandparent. What then is so significant about the few years that we spend in secondary school or in junior college that many of us have this desire to get back together with our friends from youth? I myself was in Victoria School from 1951 to early 1956. When I was doing my O levels in 1954 a group of 12 of us formed a study group. We are all in different professions and two of us have passed away in the last two years. Yet every year we still meet at least once a year with our spouses over dinner. That may be why I have not attended the OVA gatherings as often as I should. -

DETAIL 1 24Th February 2018 Saturday Air Rifle Wome

24th – 27th February 2018 SAFRA Yishun Indoor Air Weapons Range DAY 1 – DETAIL 1 Air Rifle Women (Open/School) 24th February 2018 Preparation and Sighting Time: 0900 hrs Saturday Start Time: 0915 hrs FP Name Organisation Event Entry 01 02 TAN HONG YING Raffles Institution (Year 5-6) ARW(S) 1st Team 03 LIM SI TING Hwa Chong Institution (College) ARW(S) 1st Team 04 FERNEL TAN QIAN NI Singapore Sports School ARW(S) 1st Team 05 CLAIRE NG WEI TENG Yishun Town Secondary School ARW(S) 1st Team 06 CHEW LIU IM Raffles Institution (Year 5-6) ARW(S) 1st Team 07 LEE JING LE Singapore Sports School ARW(S) 2nd Team 08 LIM IVY HomeTeamNS Air Gun Interest Group ARW(O) Individual 09 NICOLE CHAN SHI QI Hwa Chong Institution (College) ARW(S) 1st Team 10 11 TAN MEI YI RENEE SAFRA Shooting Club ARW(O) 1st Team 12 YEO SHI NING KYM Yishun Town Secondary School ARW(S) 1st Team 13 ZHENG XIAYU Hwa Chong Institution (College) ARW(S) 1st Team 14 NUS National University of Singapore ARW(O) 1st Team 15 LEE KELLI-ANN Raffles Institution (Year 5-6) ARW(S) 2nd Team 16 JOY PNG SAFRA Shooting Club ARW(O) 1st Team 17 18 LONG HUI YING NATALIE Yishun Town Secondary School ARW(S) 3rd Team 19 CECILIA NG Singapore Sports School ARW(S) 1st Team 20 ONG TZE YEE CLAIRE Hwa Chong Institution (College) ARW(S) Individual 21 TAY SEE YEN SOPHIE Raffles Institution (Year 5-6) ARW(S) 1st Team 22 CALLIE SIAH YONG XIN Singapore Sports School ARW(S) 2nd Team 23 RAUDHAH NAFISAH BTE HAKIM Yishun Town Secondary School ARW(S) Individual 24 NURUL SYAFIQA BINTE NASSARUDDIN Singapore Sports School -

The Torch • Spring 2018 • the University of Victoria Alumni

Torch 2018 Spring.qxp_Torch 2018-06-08 9:02 PM Page 1 spring 2018 ToRUvic ch Game Changers innovative Uvic profs and alUmni who are leading their fields Plus: Author Eden Robinson | Martlet at 70 | Indigenous Entrepreneurs Torch 2018 Spring.qxp_Torch 2018-06-08 9:02 PM Page 2 on campUs Monday Movement PhotogRAPhy by gREg MIllER Movement, music and collaboration were the focus of an advanced ballet class held Monday nights at the studio in the Centre for Athletics, Recreation and Special Abilities (CARSA). e recreation class, led by UVic PhD student Marla MacKinnon, rehearsed for a showcase, with piqué turns and pirouettes to original choreography she created to the song “River” by Leon Bridges. Torch 2018 Spring.qxp_Torch 2018-06-08 9:03 PM Page 1 Torch 2018 Spring.qxp_Torch 2018-06-08 9:03 PM Page 2 Table of Contents Uvic torch alumni magazine • spring 2018 Features 18 champions of innovation 12 trickster Business We profile seven outstanding members of the UVic Multiple award-winning Haisla novelist Eden community who are leading in their fields, pushing Robinson mixes Indigenous mythology with boundaries and making a difference — including contemporary issues in a hot new trilogy. baseball boss JC Fraser, professors Elizabeth Borycki, by John thRElfAll, bA ’96 Sandrina de Finney, Fraser Hof, Chris Kennedy, Helga orson, and alum Patrick McFadden. 17 Building entrepreneurs Developed in partnership with the Tribal Resources Investment Corporation (TRICORP) and the University of Victoria’s Gustavson School of Business, the what’s new with You? Aboriginal Canadian Entrepreneurs Program provides culturally appropriate business education in Be in the next class notes. -

PSC Annual Report 2008

2 Chairman’s Review 5 Members of the Singapore Public Service Commission 8 Role of the Public Service Commission 9 PSC Scholarships 2008 13 2008 PSC Scholars 28 Visits by Foreign Delegations 30 Appointments, Promotions, Appeals and Discipline 33 PSC Secretariat Staff Singapore Public Service Commission ANNUAL REPORT 2008 2 Singapore Public Service Commission Annual Report 2008 3 Chairman’s Review ntegrity, impartiality and meritocracy are the three fundamental principles in Singapore’s public governance. Since its inception in 1951, the Public Service Commission (PSC) has served as the custodian of these values for the Singapore Public Service. Th ey provide the foundation for PSC’s mission in appointing and promoting public offi cers, deciding on disciplinary matters and appeals for promotions, as well as selecting scholars. However, the PSC recognizes that a forward-looking Public Service needs to adapt to, and Ieven be a few steps ahead of, the changing environment. Over the last 58 years, the PSC has changed in order to ensure that the Singapore Public Service remains the employer of choice and continues to attract its fair share of Singapore’s talent. In 2008, PSC launched the internship programme for Junior College (JC) students. Th e internship is meant to enthuse top JC students to take up PSC scholarships and work in the civil service. Th e programme comprises work attachments to government agencies, learning journeys and dialogue sessions with senior civil servants. In all, 59 students and 14 agencies participated in the inaugural programme. Projects ranged from studying casino-related off ences to developing training materials for aviation psychologists – a refl ection of the scope and complexity of public administration in Singapore. -

The Grand Final of the Singapore Secondary

Singapore Secondary Schools Debating Championships Grand Finalist Schools Division I Division II Division III Year Champions Runners-Up Champions Runners-Up Champions Runners-Up Anglo-Chinese National Junior Chung Cheng Bukit Batok Catholic High Raffles 2014 School College High School Secondary School Institution (Barker Road) (Junior High) (Yishun) School Anglo-Chinese National Junior Serangoon Raffles Temasek Tanjong Katong 2013 School College Secondary Institution Academy Girls’ School (Independent) (Junior High) School Jurong Orchid Park Raffles Hwa Chong N.U.S. High River Valley 2012 Secondary Secondary Institution Institution School High School School School National C.H.I.J. Singapore Ngee Ann Westwood Raffles 2011 Junior College St. Joseph’s American Secondary Secondary Institution (Junior High) Convent School School School St. Anthony’s Anglo-Chinese C.H.I.J. Kent Ridge Hwa Chong Raffles Canossian 2010 School St. Joseph’s Secondary Institution Institution Secondary (Barker Road) Convent School School Global Indian Paya Lebar C.H.I.J. Jurong Raffles Hwa Chong International 2009 Methodist Girls’ St. Joseph’s Secondary Institution Institution School School Convent School (Queenstown) Fairfield S.J.I. Yishun Town Raffles Nanyang Girls’ Methodist Nan Chiau 2008 International Secondary Institution High School Secondary High School School School School Singapore Xinmin Anglo-Chinese Bowen Catholic High Nan Hua 2007 Chinese Girls’ Secondary School Secondary School High School School School (Barker Road) School Anglo-Chinese Queenstown Bukit View Methodist Girls’ Temasek Victoria Junior 2006 School College Secondary Secondary School Academy (Independent) (Integrated Programme) School School Anglo-Chinese National Junior St. Margaret’s Tanjong Katong Raffles Dunman High 2005 School College Secondary Secondary Institution School (Independent) (Junior High) School School Anglo-Chinese United World C.H.I.J.