Antifragility and the Right to the City: the Regeneration of Al Manshiya and Neve Tzedek, Tel Aviv-Jaffa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’S First Decades

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’s First Decades Rotem Erez June 7th, 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Kipfer A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Student Signature: _____________________ Supervisor Signature:_____________________ Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1: A Comparative Study of the Early Years of Colonial Casablanca and Tel-Aviv ..................... 19 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Historical Background ............................................................................................................................ -

Rates, Indications, and Speech Perception Outcomes of Revision Cochlear Implantations

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Rates, Indications, and Speech Perception Outcomes of Revision Cochlear Implantations Doron Sagiv 1,2,*,†,‡, Yifat Yaar-Soffer 3,4,‡, Ziva Yakir 3, Yael Henkin 3,4 and Yisgav Shapira 1,2 1 Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer 5262100, Israel; [email protected] 2 Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv City 6997801, Israel 3 Hearing, Speech, and Language Center, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer 5262100, Israel; [email protected] (Y.Y.-S.); [email protected] (Z.Y.); [email protected] (Y.H.) 4 Department of Communication Disorders, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv City 6997801, Israel * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +972-35-302-242; Fax: +972-35-305-387 † Present address: Department of Oolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, University of California Davis, Sacramento, CA 95817, USA. ‡ Sagiv and Yaar-Soffer contributed equally to this study and should be considered joint first author. Abstract: Revision cochlear implant (RCI) is a growing burden on cochlear implant programs. While reports on RCI rate are frequent, outcome measures are limited. The objectives of the current study were to: (1) evaluate RCI rate, (2) classify indications, (3) delineate the pre-RCI clinical course, and (4) measure surgical and speech perception outcomes, in a large cohort of patients implanted in a tertiary referral center between 1989–2018. Retrospective data review was performed and included patient demographics, medical records, and audiologic outcomes. Results indicated that RCI rate Citation: Sagiv, D.; Yaar-Soffer, Y.; was 11.7% (172/1465), with a trend of increased RCI load over the years. -

Zefat, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century C.E. Epitaphs from the Jewish Cemetery

1 In loving memory of my mother, Batsheva Friedman Stepansky, whose forefathers arrived in Zefat and Tiberias 200 years ago and are buried in their ancient cemeteries Zefat, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century C.E. Epitaphs from the Jewish Cemetery Yosef Stepansky, Zefat Introduction In recent years a large concentration of gravestones bearing Hebrew epitaphs from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries C.E. has been exposed in the ancient cemetery of Zefat, among them the gravestones of prominent Rabbis, Torah Academy and community leaders, well-known women (such as Rachel Ha-Ashkenazit Iberlin and Donia Reyna, the sister of Rabbi Chaim Vital), the disciples of Rabbi Isaac Luria ("Ha-ARI"), as well as several until-now unknown personalities. Some of the gravestones are of famous Rabbis and personalities whose bones were brought to Israel from abroad, several of which belong to the well-known Nassi and Benvenisti families, possibly relatives of Dona Gracia. To date (2018) some fifty gravestones (some only partially preserved) have been exposed, and that is so far the largest group of ancient Hebrew epitaphs that may be observed insitu at one site in Israel. Stylistically similar epitaphs can be found in the Jewish cemeteries in Istanbul (Kushta) and Salonika, the two largest and most important Jewish centers in the Ottoman Empire during that time. Fig. 1: The ancient cemetery in Zefat, general view, facing north; the bottom of the picture is the southern, most ancient part of the cemetery. 2 Since 2010 the southernmost part of the old cemetery of Zefat (Fig. 1; map ref. 24615/76365), seemingly the most ancient part of the cemetery, has been scrutinized in order to document and organize the information inscribed on the oldest of the gravestones found in this area, in wake of and parallel with cleaning-up and preservation work conducted in this area under the auspices of the Zefat religious council. -

Tel Aviv Elite Guide to Tel Aviv

DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES TEL AVIV ELITE GUIDE TO TEL AVIV HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV 3 ONLY ELITE 4 Elite Traveler has selected an exclusive VIP experience EXPERT RECOMMENDATIONS 5 We asked top local experts to share their personal recommendations ENJOY ELEGANT SEA-FACING LUXURY AT THE CARLTON for the perfect day in Tel Aviv WHERE TO ➤ STAY 7 ➤ DINE 13 ➤ BE PAMPERED 16 RELAX IN STYLE AT THE BEACH WHAT TO DO ➤ DURING THE DAY 17 ➤ DURING THE NIGHT 19 ➤ FEATURED EVENTS 21 ➤ SHOPPING 22 TASTE SUMPTUOUS GOURMET FLAVORS AT YOEZER WINE BAR NEED TO KNOW ➤ MARINAS 25 ➤ PRIVATE JET TERMINALS 26 ➤ EXCLUSIVE TRANSPORT 27 ➤ USEFUL INFORMATION 28 DISCOVER CUTTING EDGE DESIGNER STYLE AT RONEN ChEN (C) ShAI NEIBURG DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES ELITE DESTINATION GUIDE | TEL AVIV www.elitetraveler.com 2 HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV Don’t miss out on the wealth of attractions, adventures and experiences on offer in ‘The Miami of the Middle East’ el Aviv is arguably the most unique ‘Habuah’ (‘The Bubble’), for its carefree Central Tel Aviv’s striking early 20th T city in Israel and one that fascinates, and fun-loving atmosphere, in which century Bauhaus architecture, dubbed bewilders and mesmerizes visitors. the difficult politics of the region rarely ‘the White City’, is not instantly Built a mere century ago on inhospitable intrudes and art, fashion, nightlife and attractive, but has made the city a World sand dunes, the city has risen to become beach fun prevail. This relaxed, open vibe Heritage Site, and its golden beaches, a thriving economic hub, and a center has seen Tel Aviv named ‘the gay capital lapped by the clear azure Mediterranean, of scientific, technological and artistic of the Middle East’ by Out Magazine, are beautiful places for beautiful people. -

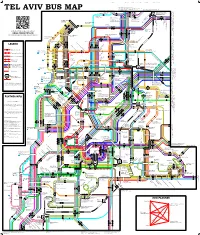

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Izraelský Kaleidoskop

Kaleidoscope of Israel Notes from a travel log Jitka Radkovičová - Tiki 1 Contents Autumn 2013 3 Maud Michal Beer 6 Amira Stern (Jabotinsky Institute), Tel Aviv 7 Yael Diamant (Beit ‑Haedut), Nir Galim 9 Tel Aviv and other places 11 Muzeum Etzel 13 Intermezzo 14 Chava a Max Livni, Kiryat Ti’von 14 Kfar Hamakabi 16 Beit She’arim 18 Alexander Zaid 19 Neot Mordechai 21 Eva Adorian, Ma’ayan Zvi 24 End of the first phase 25 Spring 2014 26 Jabotinsky Institute for the second time 27 Shoshana Zachor, Kfar Saba 28 Maud Michal Beer for the second time 31 Masada, Brit Trumpeldor 32 Etzel Museum, Irgun Zvai Leumi Muzeum, Tel Aviv 34 Kvutsat Yavne and Beit ‑Haedut 37 Ruth Bondy, Ramat Gan 39 Kiryat Tiv’on again 41 Kfar Ruppin (Ruppin’s village) 43 Intermezzo — Searching for Rudolf Menzeles (aka Mysteries remains even after seventy years) 47 Neot Mordechai for the second time 49 Yet again Eva Adorian, Ma’ayan Zvi and Ramat ha ‑Nadiv 51 Věra Jakubovič, Sde Nehemia — or Cross the Jordan 53 Tel Hai 54 Petr Erben, Ashkelon 56 Conclusion 58 2 Autumn 2013 Here we come. I am at the check ‑in area at the Prague airport and I am praying pleadingly. I have heard so many stories about the tough boys from El Al who question those who fly to Israel that I expect nothing less than torture. It is true that the tough boy seemed quite surprised when I simply told him I am going to look for evidence concerning pre ‑war Czechoslovak scout Jews in Israeli archives. -

Places to Visit in Tel Aviv

Places to visit in Tel Aviv Tel Aviv – North The Yitzhak Rabin Center The Yitzhak Rabin Center is the national institute established by the Knesset in 1997 that advances the legacy of the late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, a path-breaking, visionary leader whose life was cut short in a devastating assassination. The Center presents Yitzhak Rabin’s remarkable life and tragic death, pivotal elements of the history of Israel, whose impact must not be ignored or forgotten lest risk the recurrence of such shattering events. The Center’s mission is to ensure that the vital lessons from this story are actively remembered and used to shape an Israeli society and leadership dedicated to open dialogue, democratic value, Zionism and social cohesion. The Center promotes activities and programs that inspire cultured, engaged and civil exchanges among the different sectors that make up the complex mosaic of Israeli society. The Israeli Museum at the Yitzhak Rabin Center is the first and only museum in Israel to explore the development of the State of Israel as a young democracy. Built in a downward spiral, the Museum presents two parallel stories: the history of the State and Israeli society, and the biography of Yitzhak Rabin. The Museum’s content was determined by an academic team headed by Israeli historian, Professor Anita Shapira. We recommend allocating from an hour and thirty minutes to two hours for a visit. The Museum experience utilizes audio devices that allow visitors to tour the Museum at their own pace. They are available in Hebrew, English and Arabic. -

Israel: a Mosaic of Cultures Touring Israel to Encounter Its People, Art, Food, Nature, History, Technology and More! May 30- June 11, 2018 (As of 8/28/17)

Israel: A Mosaic of Cultures Touring Israel to encounter its People, Art, Food, Nature, History, Technology and more! May 30- June 11, 2018 (As of 8/28/17) Day 1: Wednesday May 30, 2018: DEPARTURE Depart the United States via United Airlines on our overnight flight to Israel. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Day 2: Thursday, May 31, 2018: WELCOME TO ISRAEL! We arrive at Ben Gurion Airport in the early afternoon, and are assisted by an Ayelet Tours representative. Welcome home! Our tour begins with a visit to Independence Hall, site of the signing of Israel’s Declaration of Independence in 1948, including the special exhibits for Israel’s 70th. We conclude our visit with a moving rendition of Hatikva. We travel now from the past to the present. We visit the Taglit Innovation Center for a glimpse into Israel’s hi-tech advances in the fields of science, medicine, security and space. We visit the interactive exhibit and continue with a meeting with one of Israel’s leading entrepreneurs. We check in to our hotel and have time to refresh. This evening, we enjoy a welcome dinner and tour orientation with our expert guide at a local gourmet restaurant Overnight at the Crowne Plaza Hotel, Tel Aviv --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Day 3: Friday, June 1, 2018: ISRAEL PAST TO PRESENT Breakfast at our hotel. Visit the Israel Sports Center for the Disabled in Ramat Gan for a special program with Paralympic medal winner, Pascale Bercovitch. Experience the multi-ethnic weave of Tel Aviv through tastings at the bustling Levinsky Market, with tastes and aromas from all over the Balkans and Greek Isles. -

The Strategic Plan for Tel Aviv-Yafo

THE STRATEGIC PLAN FOR TEL AVIV-YAFO The City Vision / December 2017 THE STRATEGIC PLAN FOR TEL AVIV-YAFO The City Vision / December 2017 A Message from the Mayor This document presents the today. It has gone from being a 'disregarded city' to a 'highly updated Strategic Plan for Tel regarded city' with the largest population it ever had, and from Aviv-Yafo and sets forth the a 'waning city' to a 'booming city' that is a recognized leader and vision for the city's future in the pioneer in many fields in Israel and across the globe. coming years. Because the world is constantly changing, the city – and Approximately two decades especially a 'nonstop city' like Tel Aviv-Yafo – must remain up have elapsed since we initiated to date and not be a prisoner of the past when planning its the preparation of a Strategic future. For that reason, about two years ago we decided the Plan for the city. As part time had come to revise the Strategic Plan documents and of the change we sought to achieve at the time in how the adapt our vision to the changing reality. That way we would be Municipality was managed - and in the absence of a long-term able to address the significant changes that have occurred in plan or zoning plan that outlined our urban development – we all spheres of life since drafting the previous plan and tackle the attached considerable importance to a Strategic Plan which opportunities and challenges that the future holds. would serve as an agreed-upon vision and compass to guide As with the Strategic Plan, the updating process was also our daily operations. -

The Limits of Separation: Jaffa and Tel Aviv Before 1948—The Underground Story

– Karlinsky The Limits of Separation THE LIMITS OF SEPARATION: JAFFA AND TEL AVIV — BEFORE 1948 THE UNDERGROUND STORY In: Maoz A zaryahu and S. Ilan Troen (eds.), Tel-Aviv at 100: Myths, Memories and Realities (Indiana University Press, in print) Nahum Karlinsky “ Polarized cities are not simply mirrors of larger nationalistic ethnic conflicts, but instead can be catalysts through which conflict is exacerbated ” or ameliorated. Scott A. Bollens, On Narrow Ground: Urban Policy and Ethnic Conflict in Jerusalem and Belfast (Albany, NY, 2000), p. 326. Abstract — This article describes the development of the underground infrastructure chiefly the — water and sewerage systems of Tel Aviv and Jaffa from the time of the establishment of Tel Aviv (1909) to 1948. It examines the realization of the European-informed vision of ’ Tel Aviv s founders in regard to these underground constructs in a basically non-European context. It adds another building block, however small and partial, to the growing number of studies that aspire to reconstruct that scantily researched area of relations between Jaffa and Tel Aviv before 1948. Finally, it revisits pre-1948 ethnic and national relations ’ between the country s Jewish collective and its Palestinian Arab population through the prism of the introduction of a seemingly neutral technology into a dense urban setting, and the role played by a third party (here, mainly, the British authorities) in shaping these relations. Models of Urban Relations in Pre-1948 Palestine The urban history of pre-1948 Palestine has gained welcome momentum in recent years. Traditionally, mainstream Zionist and Palestinian historiographies concentrated mainly on the rural sector, which for both national communities symbolized a mythical attachment to “ ” the land. -

Fine Judaica, to Be Held May 2Nd, 2013

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts & autograph Letters including hoLy Land traveL the ColleCtion oF nathan Lewin, esq. K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, m ay 2nd, 2013 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 318 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . PRINTED BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, & AUTOGRAPH LETTERS INCLUDING HOLY L AND TR AVEL THE COllECTION OF NATHAN LEWIN, ESQ. ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, May 2nd, 2013 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, April 28th - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, April 29th - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Tuesday, April 30th - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, May 1st - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Pisgah” Sale Number Fifty-Eight Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. Insel Client Accounts: S. Rivka Morris Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. (Consultant) Printed Books & Manuscripts: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial & Graphic Art: Abigail H. -

Tel Aviv University the Buchmann Faculty of Law

TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY THE BUCHMANN FACULTY OF LAW HANDBOOK FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS 2014-2015 THE OFFICE OF STUDENT EXCHANGE PROGRAM 1 Handbook for International Students Tel Aviv University, the Buchmann Faculty of Law 2014-2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 4 I. The Buchmann Faculty of Law 4 II. About the student exchange program 4 III. Exchange Program Contact persons 5 IV. Application 5 V. Academic Calendar 6 2. ACADEMIC INFORMATION 7 I. Course registration and Value of Credits 7 II. Exams 8 III. Transcripts 9 IV. Student Identification Cards and TAU Email Account 9 V. Hebrew Language Studies 9 VI. Orientation Day 9 3. GENERAL INFORMATION 10 I. Before You Arrive 10 1. About Israel 10 2. Currency and Banks 10 3. Post Office 11 4. Cellular Phones 11 5. Cable TV 12 6. Electric Appliances 12 7. Health Care & Insurance 12 8. Visa Information 12 II. Living in Tel- Aviv 13 1. Arriving in Tel- Aviv 13 2. Housing 13 3. Living Expenses 15 4. Transportation 15 2 III. What to Do in Tel-Aviv 17 1. Culture & Entertainment 17 2. Tel Aviv Nightlife 18 3. Restaurants and Cafes 20 4. Religious Centers 23 5. Sports and Recreation 24 6. Shopping 26 7. Tourism 26 8. Emergency Phone Numbers 27 9. Map of Tel- Aviv 27 4. UNIVERSITY INFORMATION 28 1. Important Phone Numbers 28 2. University Book Store 29 3. Campus First Aid 29 4. Campus Dental First Aid 29 5. Law Library 29 6. University Map 29 7. Academic Calendar 30 3 INTRODUCTION The Buchmann Faculty of Law Located at the heart of Tel Aviv, TAU Law Faculty is Israel’s premier law school.