Buddhist Monks As Healers in Early and Medieval Japan1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

The Establishment of State Buddhism in Japan

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository The Establishment of State Buddhism in Japan Tamura, Encho https://doi.org/10.15017/2244129 出版情報:史淵. 100, pp.1-29, 1968-03-01. Faculty of Literature, Kyushu University バージョン: 権利関係: - 1 - THE ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE BUDDHISM IN JAPAN Encho Tamura In ancient times, during the Yamato period, it was the custom for each succeeding emperor at the beginning of his reign to seek some site on which to build a new imperial palace and relocate himself. In other words, successive emperors neither inherited their palaces from the previous emperor nor handed them down to the following emperor. Hardly any example is to be found of the same palace being used by more than two emperors successively. The fact that the emperor in ancient times was called by the name of the place where his palace was located* is based on this custom of seeking new sites and founding new palaces. < 1 > This custom was strictly adhered to until the 40th Emperor, Temmu (672-686 A. D.).** The palaces, though at times relocated at Naniwa (the present Osaka Prefecture), or at Cmi (Shiga Prefecture), in most cases were built in different locations within the boundary of the Yamato area (Nara Prefecture). It is true that there is a theory denying the existence of emperors previous to the 14th Emperor, Chuai, but it is clearly stated in both the Kojiki and the Nihonshoki that all of the emperors including Jimmu, the 1st Emperor, strictly adhered to this custom of relocating the palace. This reflects the fact *For example, Emperor Kimmei was called "Shikishima no Kanazashi no Miya ni Arne ga shita Shiroshimesu Sumeramikoto" (The Emperor who rules the whole area under heaven at his Kanazashi Palace in Shikishima). -

The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’S Subjugation of Silla

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1993 20/2-3 The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’s Subjugation of Silla Akima Toshio In prewar Japan, the mythical tale of Empress Jingii’s 神功皇后 conquest of the Korean kingdoms comprised an important part of elementary school history education, and was utilized to justify Japan5s coloniza tion of Korea. After the war the same story came to be interpreted by some Japanese historians—most prominently Egami Namio— as proof or the exact opposite, namely, as evidence of a conquest of Japan by a people of nomadic origin who came from Korea. This theory, known as the horse-rider theory, has found more than a few enthusiastic sup porters amone Korean historians and the Japanese reading public, as well as some Western scholars. There are also several Japanese spe cialists in Japanese history and Japan-Korea relations who have been influenced by the theory, although most have not accepted the idea (Egami himself started as a specialist in the history of northeast Asia).1 * The first draft of this essay was written during my fellowship with the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, and was read in a seminar organized by the institu tion on 31 January 199丄. 1 am indebted to all researchers at the center who participated in the seminar for their many valuable suggestions. I would also like to express my gratitude to Umehara Takeshi, the director general of the center, and Nakanism Susumu, also of the center, who made my research there possible. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Guangxiao Temple (Guangzhou) and Its Multi Roles in the Development of Asia-Pacific Buddhism

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 8, No. 1; 2016 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Guangxiao Temple (Guangzhou) and its Multi Roles in the Development of Asia-Pacific Buddhism Xican Li1 1 School of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China Correspondence: Xican Li, School of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou Higher Education Mega Center, 510006, Guangzhou, China. Tel: 86-203-935-8076. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 21, 2015 Accepted: August 31, 2015 Online Published: September 2, 2015 doi:10.5539/ach.v8n1p45 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v8n1p45 Abstract Guangxiao Temple is located in Guangzhou (a coastal city in Southern China), and has a long history. The present study conducted an onsite investigation of Guangxiao’s precious Buddhist relics, and combined this with a textual analysis of Annals of Guangxiao Temple, to discuss its history and multi-roles in Asia-Pacific Buddhism. It is argued that Guangxiao’s 1,700-year history can be seen as a microcosm of Chinese Buddhist history. As the special geographical position, Guangxiao Temple often acted as a stopover point for Asian missionary monks in the past. It also played a central role in propagating various elements of Buddhism, including precepts school, Chan (Zen), esoteric (Shingon) Buddhism, and Pure Land. Particulary, Huineng, the sixth Chinese patriarch of Chan Buddhism, made his first public Chan lecture and was tonsured in Guangxiao Temple; Esoteric Buddhist master Amoghavajra’s first teaching of esoteric Buddhism is thought to have been in Guangxiao Temple. -

Ludvik KCJS Syllabus Spring 2018Rev

From India to Japan Patterns of Transmission and Innovation in Japanese Buddhism KCJS, Spring 2018 Catherine Ludvik Class Time: Mon & Fri 1:10–2:40 Course Description This course takes students on a pan-Asian journey from India to Japan, via the Silk Road, through an exploration of the origins, transmission and assimilation of selected themes in Japanese Buddhism, and their subsequent developments within Japan. We trace the beginnings and metamorphoses of selected figures of the Japanese Buddhist pantheon, like the ancient Indian river goddess Sarasvatī who is worshipped in Japan as Benzaiten, and of certain ritual practices, like the Japanese goma fire ceremonies and their relationship to the Vedic homa rites of India, and we study about some of the illustrious Indian, Chinese and Japanese monks who functioned as their transmitters. By way of these themes, we examine patterns of transmission and innovation. The aim of this course is to provide a wider Asian context and a layered understanding for what students encounter in the many temples of Kyoto and nearby Nara, and in the numerous festivals and ceremonies that take place within them. Themes discussed in class will be amply illustrated through field trips to temples and festivals. Course Materials There is no single textbook. Readings are listed in the Course Outline below. Course Requirements and Grading Policy 1. Attendance and participation in classes and field trips, timely completion of the required readings, contribution to class discussions (15%) Attendance: please be sure to arrive on time and prepared for class. If you are more than 30 minutes late, you will be counted as absent. -

Shintō and Buddhism: the Japanese Homogeneous Blend

SHINTŌ AND BUDDHISM: THE JAPANESE HOMOGENEOUS BLEND BIB 590 Guided Research Project Stephen Oliver Canter Dr. Clayton Lindstam Adam Christmas Course Instructors A course paper presented to the Master of Ministry Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Ministry Trinity Baptist College February 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Stephen O. Canter All rights reserved Now therefore fear the LORD, and serve him in sincerity and in truth: and put away the gods which your fathers served −Joshua TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... vii Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Chapter One: The History of Japanese Religion..................................................................3 The History of Shintō...............................................................................................5 The Mythical Background of Shintō The Early History of Shintō The History of Buddhism.......................................................................................21 The Founder −− Siddhartha Gautama Buddhism in China Buddhism in Korea and Japan The History of the Blending ..................................................................................32 The Sects That Were Founded after the Blend ......................................................36 Pre-War History (WWII) .......................................................................................39 -

Buddhist Sculpture and the State: the Great Temples of Nara Samuel Morse, Amherst College November 22, 2013

Arts of Asia Lecture Series Fall 2013 The Culture and Arts of Korea and Early Japan Sponsored by The Society for Asian Art Buddhist Sculpture and the State: The Great Temples of Nara Samuel Morse, Amherst College November 22, 2013 Brief Chronology 694 Founding of the Fujiwara Capital 708 Decision to move the capital again is made 710 Founding of the Heijō (Nara) Capital 714 Kōfukuji is founded 716 Gangōji (Hōkōji) is moved to Heijō 717 Daianji (Daikandaiji) is moved to Heijō 718 Yakushiji is moved to Heijō 741 Shōmu orders the establishment of a national system of monasteries and nunneries 743 Shōmu vows to make a giant gilt-bronze statue of the Cosmic Buddha 747 Casting of the Great Buddha is begun 752 Dedication of the Great Buddha 768 Establishment of Kasuga Shrine 784 Heijō is abandoned; Nagaoka Capital is founded 794 Heian (Kyoto) is founded Yakushiji First established at the Fujiwara Capital in 680 by Emperor Tenmu on the occasion of the illness of his consort, Unonosarara, who later took the throne as Empress Jitō. Moved to Heijō in 718. Important extant eighth century works of art include: Three-storied Pagoda Main Image, a bronze triad of the Healing Buddha, ca. 725 Kōfukuji Tutelary temple of the Fujiwara clan, founded in 714. One of the most influential monastic centers in Japan throughout the temple's history. Original location of the statues of Bonten and Taishaku ten in the collection of the Asian Art Museum. Important extant eighth century works include: Statues of the Ten Great Disciples of the Buddha Statues of the Eight Classes of Divine Protectors of the Buddhist Faith Tōdaiji Temple established by the sovereign, Emperor Shōmu, and his consort, Empress Kōmyō as the central institution of a countrywide system of monasteries and nunneries. -

Baekje's Relationship with Japan in the 6Th Century G G G PARK, Hyun-Sook* G G Introduction

International Journal of Korean History(Vol.11, Dec. 2007) 97 G G G Baekje's Relationship with Japan in the 6th Century G G G PARK, Hyun-Sook* G G Introduction The goal of the present study is to elucidate the nature of foreign relations between Baekje (ᓏ᱕) and Japan's Yamato regime in the 6th century. The relations between Korea and Japan in the 6th century is recorded extensively in ØNihon Shoki (ᬝᔲᙠᄀ)Ù. Although Japan had relations with several countries in Korea, the focus of the book is heavily placed on Baekje. Therefore, unveiling the nature of foreign relations between Baekje and the Yamato regime of Japan in the 6th century is important to determine the actual situation of Korea-Japan relations in ancient times. One major theme in research trends1 concerning the relations between 6th century Baekje and Japan's Yamato regime is the continuity found between the ‘Imna-Ilbon Bu (ᬢᄧᬝᔲᕒ)’ of the “Wai (ᦖ)” after the 4th century and the tributary foreign relation policy of Baekje. Conversely, in Korea, a mutually beneficial relationship existed between Baekje and Japan Baekje provided advanced cultural resources and Japan provided military power. Thus, the mutual understanding based on tactical foreign relation policy2 defined the relations between these two countries. In this GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG * Professor, Department of History Education, Korea University. 98 Baekje's Relationship with Japan in the 6th Century light, studies of Korean and Japan relations were not able to clarify reality due to the understanding of others through their own perspectives. Basically, the standpoint of Japanese historians has centered on the Yamato regime and on its dynamical relations with the Three Kingdoms of the Korean peninsula. -

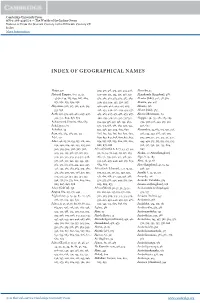

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

Works of Famous Calligrapher on Show

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Friday, May 29, 2020 | 17 LIFE SHANGHAI Works of famous calligrapher on show Calligraphy pieces and poems reveal the personality and vision of Zhao Puchu as a patriot, a social activist and a scholar, Zhang Kun reports in Shanghai. he exhibition, Infinite was his mission in life to serve the details his understanding of Bud- Compassion: The Calligra- people and society. dhism and his work promoting reli- phy of Zhao Puchu, which As early as in 1928, Zhao became gious tolerance and Chinese provides a glimpse into the a leader in Buddhist associations in religious policies; and the last chap- Zhao played an Tlife of the patriotic religious leader, Shanghai and the Yangtze Delta ter, A Man of Virtue, consists of writ- opened at Shanghai Museum on regions. In 1938, as a religious lead- ing that reflects upon his life of important role in May 21, the 20th anniversary of his er and active member of the nation- selfless contributions and righteous facilitating cultural death. al salvation movement against the conduct. Zhao was president of the Bud- Japanese invasion, Zhao built a A calligraphy work by Zhao was exchanges between dhist Association of China, a famous home for orphans and refugees of among the exhibits of A Blessing China and Japan.” social activist and a close friend of the war, sheltering up to 500,000 over the Sea: Cultural Relics on Ling Lizhong, head of the the Communist Party of China. He people. Jianzhen and Murals by Higashi- research center of paintings was also one of the most recognized During this period, he became yama Kaii from Toshodaiji, an exhi- and calligraphy at Shanghai calligraphers, poets and authors in close friends with members of the bition which concluded at Shanghai Museum China.