Shirazeh Houshiary Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SH-Sculpture 07-08.00 Text

Sculpture July/August 2000 From Form to Formlessness A Conversation with Shirazeh Houshiary By Anne Barclay Morgan Born in Shiraz, Persia, in 1955, Shirazeh Houshiary moved to London in 1973, pursuing her studies at the Chelsea School of Art. She became well known in Europe for her sculptures and was included in the 1989 Paris exhibition of world art "Magiciens de la Terre." In her artwork, Houshiary seeks to embody spiritual principles in order to manifest invisible processes or the dematerialization of form. Her earlier sculptures, with titles such as The Angel with Ten Thousand Wings or The Earth is an Angel, of the late 1980s, were made predominantly of copper, at times combined with brass. These floor sculptures contain curves in abstract shapes that suggest calligraphy. In the 1990s, her sculptures became more geometric. For example, her four-part piece Turning Around the Centre is composed of cubes of lead with recessed sections lined with gold leaf. Exhibitions of the work included works of graphite and acrylic on paper accompanied by quotations from the 13th-century Sufi poet, Rumi. Her sculptures have been included in numerous indoor and outdoor exhibitions, and she was nominated by the Tate Gallery for the Turner Prize in 1994. In September of 1999, she exhibited a new body of work at Lehmann Maupin Gallery in New York, in which she wanted to break through notions of specific media and specific nomenclature. Although her new work could be considered two dimensional, she advocates for it to be considered neither two-dimensional nor three-dimensional. Anne Barclay Morgan: What is the evolution of your new work? Shirazeh Houshiary: I began this body of work five years ago. -

Rice Public Art Announces Four New Works by Women Artists

RICE PUBLIC ART ANNOUNCES FOUR NEW WORKS BY WOMEN ARTISTS Natasha Bowdoin, Power Flower, 2021 (HOUSTON, TX – January 26, 2021) In support of Rice University’s commitment to expand and diversify its public art collection, four original works by leading women artists will be added to the campus collection this spring. The featured artists are Natasha Bowdoin (b. 1981, West Kennebunk, ME), Shirazeh Houshiary (b. 1955, Shiraz, Iran), Beverly Pepper (b. 1922 New York, NY, d. 2020 Todi, Italy), and Pae White (b. 1963, Pasadena, CA). Three of the works are site-specific commissions. The Beverly Pepper sculpture is an acquisition of one of the last works by the artist, who died in 2020. Alison Weaver, the Suzanne Deal Booth Executive Director of the Moody Center for the Arts, said, “We are honored to add these extraordinary works to the Rice public art collection and are proud to highlight innovative women artists. We look forward to the ways these unique installations will engage students, faculty, staff, alumni and visitors in the spaces where they study, learn, live, work, and spend time.” Natasha Bowdoin’s site-specific installation will fill the central hallway of the renovated M.D. Anderson Biology Building, Shirazeh Houshiary’s glass sculpture will grace the lawn of the new Sid Richardson College, Beverly Pepper’s steel monolith will be placed adjacent to the recently completed Brockman Hall for Opera, and Pae White’s hanging sculpture will fill the rotunda of McNair Hall, home to the Jones Graduate School of Business. The four works will be installed in the first four months of the year and be on permanent view beginning May 1, 2021. -

Shirazeh Houshiary B

Shirazeh Houshiary b. 1955, Shiraz, Iran 1976-79 Chelsea School of Art, London 1979-80 Junior Fellow, Cardiff College of Art 1997 Awarded the title Professor at the London Institute Solo Exhibitions 1980 Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff 1982 Kettle's Yard Gallery, Cambridge 1983 Centro d'Arte Contemporanea, Siracusa, Italy Galleria Massimo Minini, Milan Galerie Grita Insam, Vienna 1984 Lisson Gallery, London (exh. cat.) 1986 Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam 1987 Breath, Lisson Gallery, London 1988-89 Centre d'Art Contemporain, Musée Rath, Geneva (exh. cat.), (toured to The Museum of Modern Art, Oxford) 1992 Galleria Valentina Moncada, Rome Isthmus, Lisson Gallery, London 1993 Dancing around my ghost, Camden Arts Centre, London (exh. cat.) 1993-94 Turning Around the Centre, University of Massachusetts at Amherst Fine Art Center (exh. cat.), (toured to York University Art Gallery, Ontario and to University of Florida, the Harn Museum, Gainsville) 1994 The Sense of Unity, Lisson Gallery, London 1995-96 Isthmus, Le Magasin, Centre National d'Art Contemporain, Grenoble (exh. cat.), (touring to Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht, Hochschule für angewandte Kunst, Vienna). Organised by the British Council 1997 British Museum, Islamic Gallery 1999 Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, NY 2000 Self-Portraits, Lisson Gallery, London 2002 Musuem SITE, Santa Fe, NM 2003 Shirazeh Houshiary - Recent Works, Lehman Maupin, New York Shirazeh Houshiary Tate Liverpool (from the collection) Lisson Gallery, London 2004 Shirazeh Houshiary, -

Shirazeh Houshiary the Eye Fell in Love with the Ear New York, 201 Chrystie Street 30 October ‐ 28 December, 2013 Opening Reception: Wednesday, 30 October, 6‐8 PM

Shirazeh Houshiary The eye fell in love with the ear New York, 201 Chrystie Street 30 October ‐ 28 December, 2013 Opening Reception: Wednesday, 30 October, 6‐8 PM New York, 11 October 2013 ‐ Lehmann Maupin is pleased to announce an exhibition of new work by Shirazeh Houshiary on view at 201 Chrystie Street from 30 October ‐ 28 December 2013. Shirazeh Houshiary’s sixth solo show with Lehmann Maupin features a selection of new paintings that continue to demonstrate the artist’s scale of effort and process which unites line, color, and light to shape a meditative visual experience. The eye fell in love with the ear will also include Houshiary’s new animation Dust in addition to a series of anodized aluminum twisting helical sculptures. The artist will be present for an opening reception on Wednesday, 30 October from 6 to 8 PM. Houshiary’s work explores the very nature of existence. Through her chosen media of painting, sculpture and video, the artist exposes the nature of human experience to time and space, marked by a multitude of binary ideas which include transparency and opacity, presence and absence, and light and shadow. By exploring these polarities, Houshiary illuminates unique moments suspended in time that reveal and ignite qualities that are often unseen. In creating her works the artist draws inspiration from both established formal principles of Western painting and the rich traditions of Islamic art, however the aesthetic outcome is a new order that is foreign to both. Houshiary’s paintings, which she describes as “a thin skin,” unravel concepts such as perception and cognition to suggest multiple visual planes that appear to pulse and undulate. -

Narguess Farzad SOAS Membership – the Largest Concentration of Middle East Expertise in Any Institution in Europe

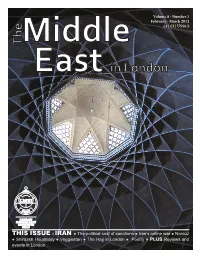

Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Interior of the dome of the house at Dawlat Abad Garden, Home of Yazd Governor in 1750 © Dr Justin Watkins About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) Volume 8 - Number 3 February – March 2012 Th e London Middle East Institute (LMEI) draws upon the resources of London and SOAS to provide teaching, training, research, publication, consultancy, outreach and other services related to the Middle Editorial Board East. It serves as a neutral forum for Middle East studies broadly defi ned and helps to create links between Nadje Al-Ali individuals and institutions with academic, commercial, diplomatic, media or other specialisations. SOAS With its own professional staff of Middle East experts, the LMEI is further strengthened by its academic Narguess Farzad SOAS membership – the largest concentration of Middle East expertise in any institution in Europe. Th e LMEI also Nevsal Hughes has access to the SOAS Library, which houses over 150,000 volumes dealing with all aspects of the Middle Association of European Journalists East. LMEI’s Advisory Council is the driving force behind the Institute’s fundraising programme, for which Najm Jarrah it takes primary responsibility. -

Alison Wilding

!"#$%&n '(h)b&#% Alison Wilding Born 1948 in Blackburn, United Kingdom Currently lives and works in London Education 1970–73 Royal College of Art, London 1967–70 Ravensbourne College of Art and Design, Bromley, Kent 1966–67 Nottingham College of Art, Nottingham !" L#xin$%on &%'##% London ()* +,-, ./ %#l +!! (+).+0+ //0!112! 1++.3++0 f24x +!! (+).+0+ //0!112! 1+.)3+0) info342'5%#564'7%#n5678h79b#'%.68om www.42'5%#64'7%#n5678h79b#'%.68om !"#$%&n '(h)b&#% Selected solo exhibitions 2013 Alison Wilding, Tate Britain, London, UK Alison Wilding: Deep Water, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2012 Alison Wilding: Drawing, ‘Drone 1–10’, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2011 Alison Wilding: How the Land Lies, New Art Centre, Roche Court Sculpture Park, Salisbury, UK Alison Wilding: Art School Drawings from the 1960s and 1970s, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2010 Alison Wilding: All Cats Are Grey…, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2008 Alison Wilding: Tracking, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2006 Alison Wilding, North House Gallery, Manningtree, UK Alison Wilding: Interruptions, Rupert Wace Ancient Art, London, UK 2005 Alison Wilding: New Drawings, The Drawing Gallery, London, UK Alison Wilding: Sculpture, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, US Alison Wilding: Vanish and Detail, Fred, London, UK 2003 Alison Wilding: Migrant, Peter Pears Gallery and Snape Maltings, Aldeburgh, UK 2002 Alison Wilding: Template Drawings, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2000 Alison Wilding: Contract, The Henry Moore Foundation Studio, Halifax, UK Alison Wilding: New Work, New -

ART in AMERICA November, 1999 Shirazeh Houshiary at Lehmann

ART IN AMERICA November, 1999 Shirazeh Houshiary at Lehmann Maupin By Edward Leffingwell In her first New York solo exhibition, the London-based Iranian painter and sculptor Shirazeh Houshiary presented a series of monochromatic paintings that invited the viewer to peer closely into their graphite-inflected surfaces to discern the minute grids and vortices of calligraphy that are central to the artist's mystic contemplation. Houshiary achieves these dense matte surfaces of either white or black with an even application of Aquacryl, a concentrated, viscous suspension of rich pigment that dries to a uniformly flat finish with a barely perceptible incidence of randomly distributed pores. She then painstakingly inscribes the delicate patterns of Sufi incantations in graphite across the black surfaces, and across the white ones in graphite, silverpoint and occasionally pencil, on canvases ranging from 11 inches to nearly 75 inches square. For Houshiary, the labor-intensive paintings of this impressive show express Sufi doctrine in both their making and viewing. They involve a search for the reconciliation of opposing forces, unification with the world and the achievement of transcendence. As a kind of prayer, these complex paintings are at once contemplative and celebratory, bearing evidence of the concentration and discipline necessary to their making, and requiring quiet study or contemplation on the part of the viewer to be perceived on any meaningful level. The fine graphite calligraphy that makes up the central element in the large black field of Unknowable (1999) appears to begin at an unseen central point and spirals out in moirélike patterns, the text repeating, gracefully opening out and becoming less dense then disappearing. -

The University Gallery Is Pleased to Present Shirazeh Houshiary

The University Gallery is pleased to present Shirazeh Houshiary; Turning Around the Centre, an exhibition of recent sculpture and drawings by an Iranian-born artist who has lived in London since 1973. One of the key figures of the group of young British sculptors who emerged in the early 1980s, Houshiary has directed herself toward exploring the resolution of material form with spiritual concepts. The artist's self-imposed challenge is to transpose personal contemplations into a visual language that does not dematerialize form, but attempts to make a physical object bear the tension between being and thought. The exhibition is on view from November 6 through December 17, 1993 with an opening reception on Friday, November 5 from 5 to 7 p.m. The artist will give a presentation about her work on Thursday, November 4 in the University Gallery at 5 p.m. From her early biomorphic forms made of clay and straw, to her "mechano-morphic" sculptures in various metals, to her more physically simple, yet conceptually complex, recent work, Houshiary's course equates art-making with soul-making. For her, the art object is a manifesation of an intermediary realm--the "imaginal" realm--that exists between body and spirit. Imagination, as defined by the artist, does not signify fantasy, which constitutes thoughts and desires tied to the finite world, but, rather, signifies the pure and infinite vision of the soul. Art, then, is the creative by-product of the soul's journey. The significance of the unsustainable moment of transformation is one of the basic themes of Houshiary's work. -

Shirazeh Houshiary String Quintet 6 SEPTEMBER - 6 OCTOBER 2012 Reception for the Artist: Thursday, 6 September, 6-8 PM Valet Parking Available

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 2012 Media Contact: Elizabeth East Telephone: 310-822-4955 SHirazeH Houshiary String Quintet 6 SEPTEMBER - 6 OCTOBER 2012 Reception for the Artist: Thursday, 6 September, 6-8 PM Valet parking available Venice, CA – L.A. Louver is pleased to present the first solo exhibition in Los Angeles for the Iranian-born, London-based artist Shirazeh Houshiary. A new sculpture by Houshiary titled String Quintet will be exhibited in L.A. Louver’s open air Skyroom. Standing 16 1/2 feet (5 meters) high, the sculpture is comprised of five slim, entwined, stainless steel forms that emerge from the ground, and reach towards the sky with twisted rhythmic force. The five tapered tendrils seem to embrace each other, then pull apart, elegantly soaring into space. Three paintings are presented in the intimate environment of L.A. Louver’s south gallery. Houshiary first maps each painting through a series of small studies. Then, working on the floor, she uses aquacryl (a water based acrylic paint) and pencil on canvas, applying numerous fine layers of medium, moving back and forth between transparency and opaqueness. The paintings evoke delicate atmospheric color fields that encourage prolonged attention. They conjure emotional states, yet remain both elusive and intangible. Beauty is their surface, and the sublime is their substance. Named after her birthplace of Shiraz, Iran, Houshiary studied at the Chelsea School of Art in London, England, and Cardiff College of Art, Wales. Houshiary has exhibited extensively in Europe and North America, including solo exhibitions at Centre d’Art Contemporain, Musée Rath, Geneva, Switzerland (traveled to the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, England), 1988-89; Camden Art Center, London, England, 1993; University of Massachusetts, Amherst Fine Art Center, MA, U.S. -

Shirazeh Houshiary

SHIRAZEH HOUSHIARY Born Shiraz, Iran, 1955 Lives London, United Kingdom EDUCATION 1997 Awarded the title of Professor at the London Institute, London, England 1980 Junior Fellow, Cardiff College of Art, Cardiff, Wales 1979 Chelsea School of Art, London, United Kingdom SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 A Thousand Folds, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY 2017 Nothing is deeper than the skin, Lisson Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Grains Swirl and the Ripples Shift, Espace Muraille, Geneva, Switzerland The River is Within Us, Singapore Tyler Print Institute, Singapore 2015 Lehmann Maupin, Hong Kong Shirazeh Houshiary: Smell of First Snow, Lisson Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2013 The eye fell in love with the ear, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY Breath, Collateral Event of the 55th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy Breath, Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai, India Shirazeh Houshiary, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY 2012 Shirazeh Houshiary, Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy String Quintet, LA Louver, Los Angeles, CA 2011 No Boundary Condition, Lisson Gallery, London, United Kingdom Altar, Saint Martin-in-the-Field Church, London, United Kingdom 2010 Light Darkness, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY 2008 Shirazeh Houshiary - New Work, Lisson Gallery, London, United Kingdom Saint Martin-in-the-Field Church, London, United Kingdom 2007 Douglas Breath, Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai, India The Paradise (28), The Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, Ireland 2006 Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY 2004 Works on Paper, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY Breath by Shirazeh -

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth British Art Studies Issue 3, published 4 July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth Cover image: Installation View, Simon Starling, Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima), 2010–11, 16 mm film transferred to digital (25 minutes, 45 seconds), wooden masks, cast bronze masks, bowler hat, metals stands, suspended mirror, suspended screen, HD projector, media player, and speakers. Dimensions variable. Digital image courtesy of the artist PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Expanding the Field: How the “New Sculpture” put British Art on the Map in the 1980s, Nick Baker Expanding the Field: How the “New Sculpture” put British Art on the Map in the 1980s Nick Baker Abstract This paper shows that sculptors attracted much of the attention that was paid to emerging British artists during the 1980s. -

'Magiciens De La Terre'

EXHIBITION REVIEWS Paris and Cologne is founded upon the observation that the a meaning which, in another context, it 'Bilderstreit' and 'Magiciens de la western 'civilised' world is introspective in might not have; but it is much the stronger Terre' its insistence on the primacy of western for it. Indeed Long is one of the few western art and that all so-called international artists to survive with credit, for many of Bilderstreit (at the Rheinhallen der exhibitions have hitherto been limited by his colleagues emerge as too calculating K61lner Messe, Cologne, 8th April to this perspective. Furthermore westerners and too reliant on strategy to withstand 28th June) 1 has been justifiably criticised regard any art which lies outside the the freshness, the directness and depth of as one of the worst conceived exhibitions western tradition as either ethnographic, meaning of the 'third world' art. Where of the decade. Taking up where Westkunst and therefore not art, or as craft. Magiciens religion, sex, death and functionalism seem left off, the organisers, Siegfried Gohr and sets out to show that contemporary art is to be the basis for the creation of most Johannes Gachnang, set out to chart the also produced within less developed coun- forms of 'ethnic' art, art itself is often the course of art in Europe and America from tries and that in the same way as western only reason for the making of western art. 1960 onwards, on the premise that Euro- artists work within, develop and deviate Although an artist such as Kiefer tackles pean art has principally been figurative from a tradition, so too do their 'third important issues, his work appears gran- while American art has been almost en- world' counterparts (Fig.103).