British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D'art Ambition D'art Alighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony

Ambition d’art AmbitionAlighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony Cragg, Luciano Fabro, Yona Friedman, Anish Kapoor, On Kawara, Martha Rosler, Jeff Wall, Lawrence Weiner d’art16 May – 21 September 2008 The Institut d’art contemporain aspect (an anniversary) and the is celebrating its 30th anniversary setting – the inauguration of an in 2008 and on this occasion exhibition in the artistico-political has invited its founder, context of the 2000s – it is aimed Jean Louis Maubant, to design at shedding light on what the an exhibition, accompanied by an ‘ambition’ of art and its ‘world’ important publication. might be. The exhibition Ambition d’art, held in partnership with the The retrospective dimension Rhône-Alpes Regional Council of the event is presented above and the town of Villeurbanne, is a all in the two volumes (Alphabet strong and exceptional event for and Archive) of the publication to the Institute: beyond the anecdotal which it has given rise. Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne www.i-art-c.org Any feedback in the exhibition is Yona Friedman, Jordi Colomer) or less to commemorate past history because they have hardly ever been than to give present and future shown (Martha Rosler, Alighiero history more density. In fact, many Boetti, Jeff Wall). Other works have of the works shown here have already been shown at the Institut never been seen before. and now gain fresh visibility as a result of their positioning in space and their artistic company (Luciano Fabro, Daniel Buren, Martha Rosler, Ambition d’art Tony Cragg, On Kawara). For the exhibition Ambition d’art, At the two ends of the generation Jean Louis Maubant has chosen chain, invitations have been eleven artists for the eleven rooms extended to both Jordi Colomer of the Institut d’art contemporain. -

SH-Sculpture 07-08.00 Text

Sculpture July/August 2000 From Form to Formlessness A Conversation with Shirazeh Houshiary By Anne Barclay Morgan Born in Shiraz, Persia, in 1955, Shirazeh Houshiary moved to London in 1973, pursuing her studies at the Chelsea School of Art. She became well known in Europe for her sculptures and was included in the 1989 Paris exhibition of world art "Magiciens de la Terre." In her artwork, Houshiary seeks to embody spiritual principles in order to manifest invisible processes or the dematerialization of form. Her earlier sculptures, with titles such as The Angel with Ten Thousand Wings or The Earth is an Angel, of the late 1980s, were made predominantly of copper, at times combined with brass. These floor sculptures contain curves in abstract shapes that suggest calligraphy. In the 1990s, her sculptures became more geometric. For example, her four-part piece Turning Around the Centre is composed of cubes of lead with recessed sections lined with gold leaf. Exhibitions of the work included works of graphite and acrylic on paper accompanied by quotations from the 13th-century Sufi poet, Rumi. Her sculptures have been included in numerous indoor and outdoor exhibitions, and she was nominated by the Tate Gallery for the Turner Prize in 1994. In September of 1999, she exhibited a new body of work at Lehmann Maupin Gallery in New York, in which she wanted to break through notions of specific media and specific nomenclature. Although her new work could be considered two dimensional, she advocates for it to be considered neither two-dimensional nor three-dimensional. Anne Barclay Morgan: What is the evolution of your new work? Shirazeh Houshiary: I began this body of work five years ago. -

Rice Public Art Announces Four New Works by Women Artists

RICE PUBLIC ART ANNOUNCES FOUR NEW WORKS BY WOMEN ARTISTS Natasha Bowdoin, Power Flower, 2021 (HOUSTON, TX – January 26, 2021) In support of Rice University’s commitment to expand and diversify its public art collection, four original works by leading women artists will be added to the campus collection this spring. The featured artists are Natasha Bowdoin (b. 1981, West Kennebunk, ME), Shirazeh Houshiary (b. 1955, Shiraz, Iran), Beverly Pepper (b. 1922 New York, NY, d. 2020 Todi, Italy), and Pae White (b. 1963, Pasadena, CA). Three of the works are site-specific commissions. The Beverly Pepper sculpture is an acquisition of one of the last works by the artist, who died in 2020. Alison Weaver, the Suzanne Deal Booth Executive Director of the Moody Center for the Arts, said, “We are honored to add these extraordinary works to the Rice public art collection and are proud to highlight innovative women artists. We look forward to the ways these unique installations will engage students, faculty, staff, alumni and visitors in the spaces where they study, learn, live, work, and spend time.” Natasha Bowdoin’s site-specific installation will fill the central hallway of the renovated M.D. Anderson Biology Building, Shirazeh Houshiary’s glass sculpture will grace the lawn of the new Sid Richardson College, Beverly Pepper’s steel monolith will be placed adjacent to the recently completed Brockman Hall for Opera, and Pae White’s hanging sculpture will fill the rotunda of McNair Hall, home to the Jones Graduate School of Business. The four works will be installed in the first four months of the year and be on permanent view beginning May 1, 2021. -

Shirazeh Houshiary B

Shirazeh Houshiary b. 1955, Shiraz, Iran 1976-79 Chelsea School of Art, London 1979-80 Junior Fellow, Cardiff College of Art 1997 Awarded the title Professor at the London Institute Solo Exhibitions 1980 Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff 1982 Kettle's Yard Gallery, Cambridge 1983 Centro d'Arte Contemporanea, Siracusa, Italy Galleria Massimo Minini, Milan Galerie Grita Insam, Vienna 1984 Lisson Gallery, London (exh. cat.) 1986 Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam 1987 Breath, Lisson Gallery, London 1988-89 Centre d'Art Contemporain, Musée Rath, Geneva (exh. cat.), (toured to The Museum of Modern Art, Oxford) 1992 Galleria Valentina Moncada, Rome Isthmus, Lisson Gallery, London 1993 Dancing around my ghost, Camden Arts Centre, London (exh. cat.) 1993-94 Turning Around the Centre, University of Massachusetts at Amherst Fine Art Center (exh. cat.), (toured to York University Art Gallery, Ontario and to University of Florida, the Harn Museum, Gainsville) 1994 The Sense of Unity, Lisson Gallery, London 1995-96 Isthmus, Le Magasin, Centre National d'Art Contemporain, Grenoble (exh. cat.), (touring to Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht, Hochschule für angewandte Kunst, Vienna). Organised by the British Council 1997 British Museum, Islamic Gallery 1999 Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, NY 2000 Self-Portraits, Lisson Gallery, London 2002 Musuem SITE, Santa Fe, NM 2003 Shirazeh Houshiary - Recent Works, Lehman Maupin, New York Shirazeh Houshiary Tate Liverpool (from the collection) Lisson Gallery, London 2004 Shirazeh Houshiary, -

Shirazeh Houshiary the Eye Fell in Love with the Ear New York, 201 Chrystie Street 30 October ‐ 28 December, 2013 Opening Reception: Wednesday, 30 October, 6‐8 PM

Shirazeh Houshiary The eye fell in love with the ear New York, 201 Chrystie Street 30 October ‐ 28 December, 2013 Opening Reception: Wednesday, 30 October, 6‐8 PM New York, 11 October 2013 ‐ Lehmann Maupin is pleased to announce an exhibition of new work by Shirazeh Houshiary on view at 201 Chrystie Street from 30 October ‐ 28 December 2013. Shirazeh Houshiary’s sixth solo show with Lehmann Maupin features a selection of new paintings that continue to demonstrate the artist’s scale of effort and process which unites line, color, and light to shape a meditative visual experience. The eye fell in love with the ear will also include Houshiary’s new animation Dust in addition to a series of anodized aluminum twisting helical sculptures. The artist will be present for an opening reception on Wednesday, 30 October from 6 to 8 PM. Houshiary’s work explores the very nature of existence. Through her chosen media of painting, sculpture and video, the artist exposes the nature of human experience to time and space, marked by a multitude of binary ideas which include transparency and opacity, presence and absence, and light and shadow. By exploring these polarities, Houshiary illuminates unique moments suspended in time that reveal and ignite qualities that are often unseen. In creating her works the artist draws inspiration from both established formal principles of Western painting and the rich traditions of Islamic art, however the aesthetic outcome is a new order that is foreign to both. Houshiary’s paintings, which she describes as “a thin skin,” unravel concepts such as perception and cognition to suggest multiple visual planes that appear to pulse and undulate. -

Listed Exhibitions (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y Anish Kapoor Biography Born in 1954, Mumbai, India. Lives and works in London, England. Education: 1973–1977 Hornsey College of Art, London, England. 1977–1978 Chelsea School of Art, London, England. Solo Exhibitions: 2016 Anish Kapoor. Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, China. Anish Kapoor: Today You Will Be In Paradise. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City, Mexico. 2015 Descension. Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA. Kapoor Versailles. Gardens at the Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, Brussels, Belgium. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Prints from the Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR. Anish Kapoor chez Le Corbusier. Couvent de La Tourette, Eveux, France. Anish Kapoor: My Red Homeland. Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre, Moscow, Russia. 2013 Anish Kapoor in Instanbul. Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul, Turkey. Anish Kapoor Retrospective. Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany 2012 Anish Kapoor. Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Leeum – Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea. Anish Kapoor, Solo Exhibition. PinchukArtCentre, Kiev, Ukraine. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Flashback: Anish Kapoor. Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, England. Anish Kapoor. De Pont Foundation for Contemporary Art, Tilburg, Netherlands. 2011 Anish Kapoor: Turning the Wold Upside Down. Kensington Gardens, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Flashback. Nottingham Castle Museum, Nottingham, England. -

Press Release

For Immediate Release. Tony Cragg February 1 – March 10, 2012 Opening reception: Wednesday, February 1st, 6-8 pm. Marian Goodman Gallery is delighted to present an exhibition of new sculpture by Tony Cragg opening on Wednesday, February 1st, and continuing through Saturday, March 10th. The exhibition will feature recent sculptures in bronze, corten steel, wood, cast iron, and stone. Concurrently, and accompanying the gallery presentation, a group of large scale works will be exhibited at The Sculpture Garden at 590 Madison Avenue (entrance at 56th Street). The Sculpture Garden is open to the public daily from 8 am to 10 pm. Tony Cragg is one of the most distinguished contemporary sculptors working today. During the past year, there have been several important solo exhibitions of his work worldwide: Seeing Things at The Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas; Figure In/ Figure Out at The Louvre, Paris; Museum Küppersmühle für Moderne Kunst, Duisburg, Germany; Tony Cragg in 4 D from Flux to Stability at The International Gallery of Modern Art, Venice; It is, Isn’t It at the Church of San Cristoforo, Lucca, Italy; and Tony Cragg: Sculptures and Drawings at The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh. Cragg’s work developed within the context of diverse influences including early experiences in a scientific laboratory; English landscape and time-based art, a precursor to the presenting of found objects and fragments that characterized early performative work; and Minimalist sculpture, an antecedent to the stack, additive and accumulation works of the mid- seventies. Cragg has widened the boundaries of sculpture with a dynamic and investigative approach to materials, to images, and objects in the physical world, and an early use of found industrial objects and fragments. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

“NEW BRITISH SCULPTURE” and the RUSSIAN ART CONTEXT 1 Saint Petersburg Stieglitz State Academy of Art and Design, 13, Solyanoy Per., St

UDC 7.067 Вестник СПбГУ. Сер. 15. 2016. Вып. 3 A. O. Kotlomanov1,2 “NEW BRITISH SCULPTURE” AND THE RUSSIAN ART CONTEXT 1 Saint Petersburg Stieglitz State Academy of Art and Design, 13, Solyanoy per., St. Petersburg, 191028, Russian Federation 2 St. Petersburg State University, 7–9, Universitetskaya nab., St. Petersburg, 199034, Russian Federation The article examines the works of leading representatives of the “New British Sculpture” Tony Cragg and Antony Gormley. The relevance of the text is related to Tony Cragg’s recent retrospective at the Hermitage Museum. Also it reviews the circumstances of realizing the 2011 exhibition project of Ant- ony Gormley at the Hermitage. The problem is founded on the study of the practice of contemporary sculpture of the last thirty years. The author discusses the relationship of art and design and the role of the financial factors in contemporary art culture. The text is provided with examples of individual theoretical and self-critical statements of Tony Cragg and Antony Gormley. It makes a comparison of the Western European art context and Russian tendencies in this field as parallel trends of creative thinking. Final conclusions formulate the need to revise the criteria of art theory and art criticism from the point of recognition of new commercial art and to determine its role in the culture of our time. Refs 5. Figs 7. Keywords: Tony Cragg, Antony Gormley, New British Sculpture, Hermitage, contemporary art, contemporary sculpture. DOI: 10.21638/11701/spbu15.2016.303 «НОВАЯ БРИТАНСКАЯ СКУЛЬПТУРА» И РОССИЙСКИЙ ХУДОЖЕСТВЕННЫЙ КОНТЕКСТ А. О. Котломанов1,2 1 Санкт-Петербургская государственная художественно-промышленная академия им. -

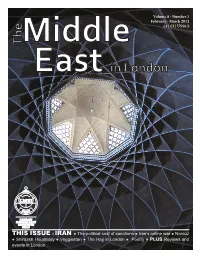

Narguess Farzad SOAS Membership – the Largest Concentration of Middle East Expertise in Any Institution in Europe

Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Interior of the dome of the house at Dawlat Abad Garden, Home of Yazd Governor in 1750 © Dr Justin Watkins About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) Volume 8 - Number 3 February – March 2012 Th e London Middle East Institute (LMEI) draws upon the resources of London and SOAS to provide teaching, training, research, publication, consultancy, outreach and other services related to the Middle Editorial Board East. It serves as a neutral forum for Middle East studies broadly defi ned and helps to create links between Nadje Al-Ali individuals and institutions with academic, commercial, diplomatic, media or other specialisations. SOAS With its own professional staff of Middle East experts, the LMEI is further strengthened by its academic Narguess Farzad SOAS membership – the largest concentration of Middle East expertise in any institution in Europe. Th e LMEI also Nevsal Hughes has access to the SOAS Library, which houses over 150,000 volumes dealing with all aspects of the Middle Association of European Journalists East. LMEI’s Advisory Council is the driving force behind the Institute’s fundraising programme, for which Najm Jarrah it takes primary responsibility. -

Alison Wilding

!"#$%&n '(h)b&#% Alison Wilding Born 1948 in Blackburn, United Kingdom Currently lives and works in London Education 1970–73 Royal College of Art, London 1967–70 Ravensbourne College of Art and Design, Bromley, Kent 1966–67 Nottingham College of Art, Nottingham !" L#xin$%on &%'##% London ()* +,-, ./ %#l +!! (+).+0+ //0!112! 1++.3++0 f24x +!! (+).+0+ //0!112! 1+.)3+0) info342'5%#564'7%#n5678h79b#'%.68om www.42'5%#64'7%#n5678h79b#'%.68om !"#$%&n '(h)b&#% Selected solo exhibitions 2013 Alison Wilding, Tate Britain, London, UK Alison Wilding: Deep Water, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2012 Alison Wilding: Drawing, ‘Drone 1–10’, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2011 Alison Wilding: How the Land Lies, New Art Centre, Roche Court Sculpture Park, Salisbury, UK Alison Wilding: Art School Drawings from the 1960s and 1970s, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2010 Alison Wilding: All Cats Are Grey…, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2008 Alison Wilding: Tracking, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2006 Alison Wilding, North House Gallery, Manningtree, UK Alison Wilding: Interruptions, Rupert Wace Ancient Art, London, UK 2005 Alison Wilding: New Drawings, The Drawing Gallery, London, UK Alison Wilding: Sculpture, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, US Alison Wilding: Vanish and Detail, Fred, London, UK 2003 Alison Wilding: Migrant, Peter Pears Gallery and Snape Maltings, Aldeburgh, UK 2002 Alison Wilding: Template Drawings, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2000 Alison Wilding: Contract, The Henry Moore Foundation Studio, Halifax, UK Alison Wilding: New Work, New -

ART in AMERICA November, 1999 Shirazeh Houshiary at Lehmann

ART IN AMERICA November, 1999 Shirazeh Houshiary at Lehmann Maupin By Edward Leffingwell In her first New York solo exhibition, the London-based Iranian painter and sculptor Shirazeh Houshiary presented a series of monochromatic paintings that invited the viewer to peer closely into their graphite-inflected surfaces to discern the minute grids and vortices of calligraphy that are central to the artist's mystic contemplation. Houshiary achieves these dense matte surfaces of either white or black with an even application of Aquacryl, a concentrated, viscous suspension of rich pigment that dries to a uniformly flat finish with a barely perceptible incidence of randomly distributed pores. She then painstakingly inscribes the delicate patterns of Sufi incantations in graphite across the black surfaces, and across the white ones in graphite, silverpoint and occasionally pencil, on canvases ranging from 11 inches to nearly 75 inches square. For Houshiary, the labor-intensive paintings of this impressive show express Sufi doctrine in both their making and viewing. They involve a search for the reconciliation of opposing forces, unification with the world and the achievement of transcendence. As a kind of prayer, these complex paintings are at once contemplative and celebratory, bearing evidence of the concentration and discipline necessary to their making, and requiring quiet study or contemplation on the part of the viewer to be perceived on any meaningful level. The fine graphite calligraphy that makes up the central element in the large black field of Unknowable (1999) appears to begin at an unseen central point and spirals out in moirélike patterns, the text repeating, gracefully opening out and becoming less dense then disappearing.