George Alan Russell: Jazz's First Theorist Robert E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

94 DOWNBEAT JUNE 2019 42Nd ANNUAL

94 DOWNBEAT JUNE 2019 42nd ANNUAL JUNE 2019 DOWNBEAT 95 JeJenna McLean, from the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley, is the Graduate College Wininner in the Vocal Jazz Soloist category. She is also the recipient of an Outstanding Arrangement honor. 42nd Student Music Awards WELCOME TO THE 42nd ANNUAL DOWNBEAT STUDENT MUSIC AWARDS The UNT Jazz Singers from the University of North Texas in Denton are a winner in the Graduate College division of the Large Vocal Jazz Ensemble category. WELCOME TO THE FUTURE. WE’RE PROUD after year. (The same is true for certain junior to present the results of the 42nd Annual high schools, high schools and after-school DownBeat Student Music Awards (SMAs). In programs.) Such sustained success cannot be this section of the magazine, you will read the attributed to the work of one visionary pro- 102 | JAZZ INSTRUMENTAL SOLOIST names and see the photos of some of the finest gram director or one great teacher. Ongoing young musicians on the planet. success on this scale results from the collec- 108 | LARGE JAZZ ENSEMBLE Some of these youngsters are on the path tive efforts of faculty members who perpetu- to becoming the jazz stars and/or jazz edu- ally nurture a culture of excellence. 116 | VOCAL JAZZ SOLOIST cators of tomorrow. (New music I’m cur- DownBeat reached out to Dana Landry, rently enjoying includes the 2019 albums by director of jazz studies at the University of 124 | BLUES/POP/ROCK GROUP Norah Jones, Brad Mehldau, Chris Potter and Northern Colorado, to inquire about the keys 132 | JAZZ ARRANGEMENT Kendrick Scott—all former SMA competitors.) to building an atmosphere of excellence. -

Cedille Records CDR 90000 066 DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 066 AFRICAN HERITAGE SYMPHONIC SERIES • VOLUME III WORLD PREMIERE RECORDINGS 1 MICHAEL ABELS (B

Cedille Records CDR 90000 066 DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 066 AFRICAN HERITAGE SYMPHONIC SERIES • VOLUME III WORLD PREMIERE RECORDINGS 1 MICHAEL ABELS (b. 1962): Global Warming (1990) (8:18) DAVID BAKER (b. 1931): Cello Concerto (1975) (19:56) 2 I. Fast (6:22) 3 II. Slow à la recitative (7:17) 4 III. Fast (6:09) Katinka Kleijn, cello soloist 5 WILLIAM BANFIELD (b. 1961): Essay for Orchestra (1994) (10:33) COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON (b. 1932) Generations: Sinfonietta No. 2 for Strings (1996) (19:31) 6 I. Misterioso — Allegro (6:13) 8 III. Alla Burletta (2:04) 7 II. Alla sarabande (5:35) 9 IV. Allegro vivace (5:28) CHICAGO SINFONIETTA / PAUL FREEMAN, CONDUCTOR TT: (58:45) Sara Lee Foundation is the exclusive corporate sponsor for African Heritage Symphonic Series, Volume III This recording is also made possible in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts & The Aaron Copland Fund for Music Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are supported in part by contributions and grants from individuals, foundations, corporations, and government agencies including the Alpha- wood Foundation, the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs (CityArts III Grant), and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 066 PROGRAM NOTES by dominique-rené de lerma The quartet of composers represented here have a par- cultures, and decided to write a piece that celebrates ticular distinction in common: Each displays remarkable these common threads as well as the sudden improve- stylistic versatility, working not just in concert idioms, but ment in international relations that was occurring.” The also in film music, gospel music, and jazz. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

![Eric Dolphy Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6248/eric-dolphy-collection-finding-aid-library-of-congress-226248.webp)

Eric Dolphy Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Eric Dolphy Collection Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2014 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu014006 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2014565637 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Collection Summary Title: Eric Dolphy Collection Span Dates: 1939-1964 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1960-1964) Call No.: ML31.D67 Creator: Dolphy, Eric Extent: Approximately 250 items ; 6 containers ; 5.0 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Eric Dolphy was an American jazz alto saxophonist, flautist, and bass clarinetist. The collection consists of manuscript scores, sketches, parts, and lead sheets for works composed by Dolphy and others. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Dolphy, Eric--Manuscripts. Dolphy, Eric. Dolphy, Eric. Dolphy, Eric. Works. Selections. Mingus, Charles, 1922-1979. Works. Selections. Schuller, Gunther. Works. Selections. Subjects Composers--United States. Jazz musicians--United States. Jazz--Lead sheets. Jazz. Music--Manuscripts--United States. Saxophonists--United States. Form/Genre Scores. Administrative Information Provenance Gift, James Newton, 2014. Accruals No further accruals are expected. Processing History The Eric Dolphy Collection was processed by Thomas Barrick in 2014. Thomas Barrick coded the finding aid for EAD format in October 2014. -

Of Audiotape

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. DAVID N. BAKER NEA Jazz Master (2000) Interviewee: David Baker (December 21, 1931 – March 26, 2016) Interviewer: Lida Baker with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: June 19, 20, and 21, 2000 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 163 pp. Lida: This is Monday morning, June 19th, 2000. This is tape number one of the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project interview with David Baker. The interview is being conducted in Bloomington, Indiana, [in] Mr. Baker’s home. Let’s start with when and where you were born. David: [I was] born in Indianapolis, December 21st, 1931, on the east side, where I spent almost all my – when I lived in Indianapolis, most of my childhood life on the east side. I was born in 24th and Arsenal, which is near Douglas Park and near where many of the jazz musicians lived. The Montgomerys lived on that side of town. Freddie Hubbard, much later, on that side of town. And Russell Webster, who would be a local celebrity and wonderful player. [He] used to be a babysitter for us, even though he was not that much older. Gene Fowlkes also lived in that same block on 24th and Arsenal. Then we moved to various other places on the east side of Indianapolis, almost always never more than a block or two blocks away from where we had just moved, simply because families pretty much stayed on the same side of town; and if they moved, it was maybe to a larger place, or because the rent was more exorbitant, or something. -

20Questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker

20questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker If Benny Goodman was the “King of Swing” periodically to continue his studies over the B-Town and Edward Kennedy Ellington was “the Duke,” next decade, leading a renowned IU-based then David Baker could be called “the Dean big band while expanding his artistic and Hero and Jazz of Jazz.” Distinguished Professor of Music at compositional horizons with musical scholars Indiana University and conductor of the Smithso- such as George Russell and Gunther Schuller. nian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, he is at home In 1966 he settled in the city for good and Legend performing in concert halls, traveling around the began what is now a world-renowned jazz world, or playing in late-night jazz bars. studies program at IU’s Jacobs School of Music. Born in Indianapolis in 1931, he grew up A pioneer of jazz education, a superlative in a thriving mid-20th-century local jazz scene trombonist forced in his early 30s to switch that begat greats such as J.J. Johnson and Wes to cello, a prolific composer, Pulitzer and Montgomery. Baker first came to Bloomington Grammy nominee and Emmy winner whose as a student in the fall of 1949, returning numerous other honors include the Kennedy 56 Bloom | August/September 2007 Toddler David in Indianapolis, circa 1933. Photo courtesy of the Baker family Center for the Performing Arts “Living Jazz Legend Award,” he performs periodically in Bloomington with his wife Lida and is unstintingly generous with the precious commodity of his time. -

Aspects of Jazz and Classical Music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2002 Aspects of jazz and classical music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini Heather Koren Pinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pinson, Heather Koren, "Aspects of jazz and classical music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini" (2002). LSU Master's Theses. 2589. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2589 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASPECTS OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL MUSIC IN DAVID N. BAKER’S ETHNIC VARIATIONS ON A THEME OF PAGANINI A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in The School of Music by Heather Koren Pinson B.A., Samford University, 1998 August 2002 Table of Contents ABSTRACT . .. iii INTRODUCTION . 1 CHAPTER 1. THE CONFLUENCE OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL MUSIC 2 CHAPTER 2. ASPECTS OF MODELING . 15 CHAPTER 3. JAZZ INFLUENCES . 25 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 48 APPENDIX 1. CHORD SYMBOLS USED IN JAZZ ANALYSIS . 53 APPENDIX 2 . PERMISSION TO USE COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL . 54 VITA . 55 ii Abstract David Baker’s Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini (1976) for violin and piano bring together stylistic elements of jazz and classical music, a synthesis for which Gunther Schuller in 1957 coined the term “third stream.” In regard to classical aspects, Baker’s work is modeled on Nicolò Paganini’s Twenty-fourth Caprice for Solo Violin, itself a theme and variations. -

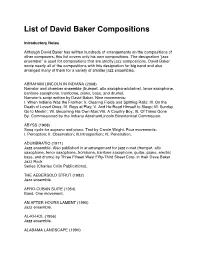

List of David Baker Compositions

List of David Baker Compositions Introductory Notes Although David Baker has written hundreds of arrangements on the compositions of other composers, this list covers only his own compositions. The designation “jazz ensemble” is used for compositions that are strictly jazz compositions. David Baker wrote nearly all of the compositions with this designation for big band and also arranged many of them for a variety of smaller jazz ensembles. ABRAHAM LINCOLN IN INDIANA (2008) Narrator and chamber ensemble (trumpet, alto saxophone/clarinet, tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, trombone, piano, bass, and drums). Narratorʼs script written by David Baker. Nine movements: I. When Indiana Was the Frontier; II. Clearing Fields and Splitting Rails; III. On the Death of Loved Ones; IV. Boys at Play; V. And He Read Himself to Sleep; VI. Sunday Go to Meetinʼ; VII. Becoming His Own Man;VIII. A Country Boy; IX. Of Times Gone By. Commissioned by the Indiana AbrahamLincoln Bicentennial Commission. ABYSS (1968) Song cycle for soprano and piano. Text by Carole Wright. Four movements: I. Perception; II. Observation; III.Introspection; IV. Penetration. ADUMBRATIO (1971) Jazz ensemble. Also published in anarrangement for jazz nonet (trumpet, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, trombone, baritone saxophone, guitar, piano, electric bass, and drums) by Three Fifteen West Fifty-Third Street Corp. in their Dave Baker Jazz Rock Series (Charles Colin Publications). THE AEBERSOLD STRUT (1982) Jazz ensemble. AFRO-CUBAN SUITE (1954) Band. One movement. AN AFTER HOURS LAMENT (1990) Jazz ensemble. AL-KI-HOL (1956) Jazz ensemble. ALABAMA LANDSCAPE (1990) Bass-baritone and orchestra. Text by Mari Evans. Commissioned by William Brown. -

Butler University School of Music Duckwall Artist Series Open Sky Bird at 100: a Tribute to Charlie Parker

BUTLER UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC DUCKWALL ARTIST SERIES presents OPEN SKY BIRD AT 100: A TRIBUTE TO CHARLIE PARKER Matt Pivec, saxophones Jesse Wittman, bass Sandy Williams, guitar Kenny Phelps, drums Steve Allee, piano Eidson-Duckwall Recital Hall Tuesday, October 13, 2020 • 7:30 P.M. The fourteenth program of the Butler University School of Music 2020-21 season PROGRAM Repertoire will be announced from the stage. BIOS MATT PIVEC As a performer of jazz and popular music, Matt has worked with Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, The Temptations, Dave Rivello, Bob Brookmeyer, Peter Erskine, Maria Schneider, Julia Dollison, Melvin Rhyne, the Buselli-Wallarab Jazz Orchestra, the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, the Rochester Philharmonic Pops Orchestra, and the national touring companies of Hairspray, 42nd Street, and The Producers. As a band leader and soloist, Matt has performed at jazz festivals and venues throughout the United States. He has three albums to his credit: Live at Snider Hall, Psalm Songs, and the recently released Time and Direction. Currently, Matt is the Director of Jazz Studies at Butler University where he leads the Jazz Ensemble and teaches courses in the jazz studies curriculum. Under his direction, Butler ensembles have performed with world-renowned guest artists such as Kurt Elling, Christian McBride, Bobby Sanabria, Donny McCaslin, Fred Sturm, Melvin Rhyne, Steve Allee, Ted Poor, and the Wee Trio. Matt received the Doctor of Musical Arts (Saxophone Performance and Literature) and Master of Music (Jazz Studies and Contemporary Media) degrees from the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. While at Eastman, Matt studied with Ramon Ricker. -

The Hard Bop Trombone: an Exploration of the Improvisational Styles of the Four Trombonist Who Defined the Genre (1955-1964)

The Hard Bop Trombone: An exploration of the improvisational styles of the four trombonist who defined the genre (1955-1964) Emmett C. Goods Dissertation submitted to the School of Music at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Trombone Performance H. Keith Jackson, DMA, Committee Chair Constinia Charbonnette, EDD David Taddie, Ph.D. Michael Vercelli, DMA Mitchell Arnold, DMA Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2019 Keywords: Hard Bop, Trombone, Jazz, Jazz Improvisation Copyright 2019 Emmett C. Goods The Hard Bop Trombone: An exploration of the improvisational styles of the four trombonist who defined the genre (1955-1964). Emmett C. Goods This dissertation examines the improvisational stylings of Curtis Fuller, Locksley “Slide” Hampton, Julian Priester and Grachan Moncur III from 1955 through 1964. In part one of this study, each musician is presented through their improvisational connections to J.J. Johnson, the leading trombonist of the Bebop era. His improvisational signatures are then traced through to the musical innovations of the Hard-Bop Trombone Era. Source material for this part of the study includes published books, dissertations, articles, online sources, discographies and personal interviews. Part two of this paper analyzes selected solos from each of the four subjects to identify the defining characteristics of the Hard-Bop Trombone Era. Evidence for these claims is bolstered by interviews conducted with the four men and their protégés. In a third and final part, a discography has been compiled for each artists during the defined era. Through historical analysis of these four artists’ music and recording of first-hand accounts from the artists themselves, this document attempts to properly contextualize the Hard-Bop Trombone Era as unique and important to the further development of the jazz trombone. -

I a COMPARATIVE STUDY of the JAZZ TRUMPET STYLES of CLIFFORD BROWN, DONALD BYRD, and FREDDIE HUBBARD an EXAMINATION of IMPROVISA

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE JAZZ TRUMPET STYLES OF CLIFFORD BROWN, DONALD BYRD, AND FREDDIE HUBBARD AN EXAMINATION OF IMPROVISATIONAL STYLE FROM 1953-1964 by JAMES HARRISON MOORE Bachelor of Music, West Virginia University, 2003 Master of Music, University of the Arts, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by James Harrison Moore It was defended on March 29, 2012 Committee Members: Dean L. Root, Professor, Music Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Music Lawrence Glasco, Professor, History Dissertation Advisor: Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music ii Copyright © by James Harrison Moore 2012 iii Nathan T. Davis, PhD A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE JAZZ TRUMPET STYLES OF CLIFFORD BROWN, DONALD BYRD, AND FREDDIE HUBBARD: AN EXAMINATION OF IMPROVISATIONAL STYE FROM 1953-1964. James Harrison Moore, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This study is a comparative examination of the musical lives and improvisational styles of jazz trumpeter Clifford Brown, and two prominent jazz trumpeters whom historians assert were influenced by Brown—Donald Byrd and Freddie Hubbard. Though Brown died in 1956 at the age of 25, the reverence among the jazz community for his improvisational style was so great that generations of modern jazz trumpeters were affected by his playing. It is widely said that Brown remains one of the most influential modern jazz trumpeters of all time. In the case of Donald Byrd, exposure to Brown’s style was significant, but the extent to which Brown’s playing was foundational or transformative has not been examined. -

National Endowment for the Arts Newsletter (Feat. Eli

VOL 1 2008 A GREAT NATION DESERVES GREAT ART A Ho t Time Up North 20 08 NEA Jazz Masters Awards 11 Bringing Jazz to a 13 Tuning In: NEA’s 14 NEA Receives 14 New Lifetime New Generation: Jazz Moments Historic Budget Achievement Award: NEA Jazz Hit the Airwaves Increase NEA Opera Honors in the Schools NEA ARTS NEA Jazz Masters Celebrating the Nation’s Highest Honor in Jazz The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) has tion, a new award cate - supported the jazz Yeld for almost 40 years. Ve Yrst gory was established: the grant for jazz was awarded in 1969—a $5,500 com - A.B. Spellman NEA Jazz position grant to composer, arranger, theoretician, Masters Award for Jazz pianist, and drummer George Russell—who would Advocacy. later receive an NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship in To maximize public 1990. By 2007, the NEA’s Ynancial support of jazz awareness of the NEA reached nearly $3 million. Jazz Masters initiative, In 1982, the NEA created the fellowship pro - new radio and television gram to recognize outstanding jazz musicians for programs were launched: artistic excellence and lifelong achievements in the Jazz Moments, a series of Yeld of jazz. With the appointment of Chairman radio segments broad - Gioia in 2004, the NEA Jazz Masters initiative was cast Yrst on XM Satellite expanded to foster a higher awareness of America’s jazz Music and Opera Director Wayne Radio, and Legends of legends. Ve number of awards was increased to six and Brown. Photo by Kevin Allen. Jazz, a television series individual fellowship stipends rose to $25,000.