The Sari As a Creative Tool in Designing a Woman's Identity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

Diadem Gold Mining Co

aiyiM iwaftwfiFBywiwftBiaww1' 1,,iw Mf MJff Wednesday, May i, 1901 THE SUMPTER MINER Diadem Gold Mining Co. : OFFICERS Mines Situated on Green- This Mine is Working j President J. H. ROBBINS J Every Day j Mayor of Sumpttr a. N.C.RICHARDS horn Mountain Attorney (Uw J This Mine is a Shiping Sec'y and Treas...OTTO HERLOCKER Baker County Mine i4 At. Cathltr First Bank ol Sumpttr f Directors J. H. Robblns, N. C. J The Baker Cl!y SamplInK Works Richards, E. M. Anderson, M. D. gives the following returns (or two Supt. of Mines... DAVID O'NEIL small shipments: Lot 68-1- . 253 sacks X Of Iter P, O.. Baker County, Oregon 1,000,000 SHARES of ore, dry weight, 13,06) pounds. In addition to the officer of the company Z Gold, 7 ounces; silver, 940 ounces. J among the atockholderi are: Hon. Lee Mantle, T : PAR VALUE $1 00 EACH Gold per oz, $20; treatment cost 98. late IT. S. Senator, Hutte, Montana: Tho. R. Net price per Freight, Hindi, County Treasurer, Butte, Montana; I ton, 130.50. late of Hon. John F. Forbes, Attorney-at-La- Butte; Zi a 97 per ton. Net value lost, 9800,24. Chas. S. Warren, Speculator, Butte; los. F. Par-- T Lot No. 102. 378 sack ore; dry dee, Miner, Phllllpsburg, Montana; H. M. Grant, weight, 18,810. Gold, 6.20 ounces; Insurance Adfuster, Portland; Geo. W, McDow- - ell, Broker Portland; CB. Richardson, Contrac- - Home Office silver, q ounces; gold $20 per ounce. tor, Walla. Walla, Wash.; Hector McRea. -

A Paratextual Analysis of Nurturing Opera Audiences: Transmedia Practices, Interactivity and Historical Interpretation in the We

. Volume 16, Issue 1 May 2019 A paratextual analysis of Nurturing Opera Audiences: Transmedia practices, interactivity and historical interpretation in the Welsh National Opera’s promotion of the ‘Tudors Trilogy’1 Rachel Grainger and Márta Minier, University of South Wales, UK Abstract: This article examines contemporary opera marketing strategies in the context of paratextuality and transmedia storytelling using the case study of the Welsh National Opera’s (WNO) 2013 ‘Tudor trilogy’ (Anna Bolena, Maria Stuarda, Roberto Devereux by Gaetano Donizetti). The WNO’s marketing, and education & outreach campaigns for their Tudor opera performances build on the contemporary manifold ‘presence of the past in British society’ (Wright 2009: ix) and the widespread use of technologically aided branding in the arts world. We will argue that the WNO’s creative and heritagising recourse to the Tudor period as ‘usable past’ (Jordanova 2006, Smith 1997: 37) and ‘playable past’ (Kapell and Elliott 2013: 362) not only determines the main branding context for the performed opera trilogy as a cultural product but that there is also a lucrative case of one brand supporting another: the Tudor brand as a phenomenon of contemporary retro-culture bolstering the WNO brand as a not exclusively upper class but accessible and chic brand. WNO’s Tudors performance cluster is a project where significant agencies and configurations of the contemporary heritage industry converge: high opera meets Tudormania, digital marketing company Yello brick and the National Trust as -

From the Garden of Eden to the New Creation in Christ : a Theological Investigation Into the Significance and Function of the Ol

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2017 From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old estamentT imagery of Eden within the New Testament James Cregan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Cregan, J. (2017). From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old Testament imagery of Eden within the New Testament (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/181 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN TO THE NEW CREATION IN CHRIST: A THEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE SIGNIFICANCE AND FUNCTION OF OLD TESTAMENT IMAGERY OF EDEN WITHIN THE NEW TESTAMENT. James M. Cregan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, Australia. School of Philosophy and Theology, Fremantle. November 2017 “It is thus that the bridge of eternity does its spanning for us: from the starry heaven of the promise which arches over that moment of revelation whence sprang the river of our eternal life, into the limitless sands of the promise washed by the sea into which that river empties, the sea out of which will rise the Star of Redemption when once the earth froths over, like its flood tides, with the knowledge of the Lord. -

Outer Garments: Copes, Cloaks and Mantles

CHAPTER 2 Outer Garments: Copes, Cloaks and Mantles Introduction was very much the province of the highest ranks, secular or ecclesiastical, in Europe. The cope is a form of vestment which has changed very In its ecclesiastical history the earliest use of the little over the centuries. It originated (like the chasuble, cope seems to have been as a hooded garment worn see chapter 3) from a Roman garment, the earliest form by monks and priests in church, probably for warmth of which was not particularly grand, called the paenula. and for protection against the weather. The Catholic This was a semi-circular cloak, open down the front, Encyclopedia notes some interesting eighth- to ninth- worn as everyday clothing by the ordinary citizen, and century mentions of a garment called a cappa (still an apparently by women and the upper classes as a pro- alternative name for a cope) which make clear that tection from the weather when travelling. This latter some were indeed everyday cloaks, others more suit- version could be made of splendid rather than merely able for liturgical wear – and in one instance that the practical material, and it was this which gradually, in garment called by some a cuculla (cowl) was the same fact very slowly, became part of ecclesiastical dress, and as that called by others a cappa, and was part of monas- even more slowly developed a ceremonial use. Because tic dress.1 This casts an interesting light on the ultimate of its originally protective function it was usually volu- origins of the Franciscan cowl of later centuries (see the minous, so that it could be wrapped around the body cowl of St Francis of Assissi, 4.4). -

Subducted Carbonates, Metasomatism of Mantle Wedges, and Possible Connections to Diamond Formation: an Example from California

American Mineralogist, Volume 90, pages xxx–xxx, 2005 Subducted carbonates, metasomatism of mantle wedges, and possible connections to diamond formation: An example from California MIHAI N. DUCEA,1,* JASON SALEEBY,2 JEAN MORRISON,3 AND VICTOR VALENCIA1 1University of Arizona, Department of Geosciences, Tucson, Arizona 85721, U.S.A. 2California Institute of Technology, Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, Pasadena, California 91125, U.S.A. 3University of Southern California, Department of Earth Sciences, Los Angeles, California 90089, U.S.A. ABSTRACT We investigated calcite globules and veins in two spinel-garnet peridotite xenoliths from the sub- Sierra Nevada mantle. The studied xenoliths were entrained in a Miocene (11 Ma) volcanic plug. These carbonates are associated spatially with silicate glass inclusions, suggesting that they are primary inclusions—inclusions that formed at high temperature in the mantle and not at or close to the Earthʼs surface. The host peridotites represent samples of the lithospheric mantle wedge beneath the Meso- zoic California magmatic arc, as indicated by radiogenic isotopic ratios measured on clinopyroxene 87 86 separates [ Sr/ Sr(11 Ma) = 0.7058–0.7061, εNd (11 Ma) = –1.9 to –0.7]. Mineral chemistry of the peridotite major phases is typical of a mantle section that was depleted of melt. The δ18O values of olivine and orthopyroxene from the two samples are also typical of mantle rocks (δ18O = 6–6.5‰). In contrast, calcite veins have δ18O of 18–20‰ and δ13C of –14‰, arguing for a subducted sedimentary origin for these carbonates. Presumably, the carbonates were expelled from the downgoing slab and fluxed into the overlying mantle wedge as CO2- or CO2-H2O-rich fluids or melts. -

On Site Opera Press Kit 2016

PRESS KIT 2016 P.O. Box 231480 | New York, NY 10023 347-394-3050 | [email protected] | www.osopera.org QUOTES Gregg Kallor's The Tell-Tale Heart • “The starkly simple production by Sarah Meyers, which placed Pojanowski in the merciless glare of a single spotlight, proved one of the most effective stagings I've seen from the always-inventive On Site Opera” –The Observer • “Part of the draw of The Crypt Sessions is its unique venue. Performances happen in the Crypt Chapel...an inspired setting for The Tell-Tale Heart—the vaulted, cloistered qualities well suited for a meditation on entombment.” –Parterre Box Dominick Argento’s Miss Havisham’s Wedding Night & Hector Berlioz’s La Mort de Cléopâtre • “I would not have wanted to hear either opera anywhere else....Without that separation from the audience, Partridge and Gaissert leveraged the closeness, relying on the transparency of their characters’ damaged psyches, indulging in murmured pianissimos and quick turns that might get lost in a bigger house. The result was both lavish and intimate.” — NY Magazine • “There was the gobsmacking experience of having the performers right there at one’s elbow, inches away – Cleopatra’s gown wafting against your shoulder as she passed, Miss Havisham’s old lace perfuming the air as her doleful countenance met yours in a transfixing intimacy. And, above all, there was the sound!” La Scena Musicale Marcos Portugal's The Marriage of Figaro • “So Much More Than Sleep No More. On Site Opera's immersive version of Marriage of Figaro is on point. This lively young cast was so irresistible that you wouldn’t ever want them to stop singing.” –The Observer • “On Site Opera presents the ultimate in intimate productions by performing works in spaces that fit the setting of the story. -

Whither Cowboy Poetry?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1999 WHITHER COWBOY POETRY? Jim Hoy Emporia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Hoy, Jim, "WHITHER COWBOY POETRY?" (1999). Great Plains Quarterly. 902. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/902 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WHITHER COWBOY POETRY? JIM HOY As a cultural phenomenon the explosion in high-heeled boots, silk neckerchief, leather popularity of cowboy poetry in the past dozen chaps-has long since become an icon that years has been nothing short of spectacular. represents the very nation: wear a cowboy hat Until the first full-scale cowboy poetry gath and you will be taken for an American any ering at Elko, Nevada, in late January 1985, where in the world. The two essential working poetry was arguably the one aspect of cowboy skills of the cowboy-roping cattle and riding culture that had not been expropriated into bucking horses-long ago have been trans American popular culture. Certainly the men formed from actual ranch work into one of the tal picture of the cowboy himself-big hat, nation's largest spectator and participant sports: rodeo. And the idealized, romanticized image of the cowboy (certainly far removed from the low-paid, hard-working hired man on horseback who actually works with cows, horses, and four-wheel-drive pickups) has be come, through pulp fiction, television, and James F. -

Spanish Open Dictionary by Alfredo Edgardo Alvarez Ahumada VOL4

SPANISH DICTIONARY Alfredo Edgardo Alvarez Ahumada Dictionary of meanings generated by www.wordmeaning.org INTRODUCTION www.wordmeaning.org is an open and collaborative dictionary project that, apart from being able to consult meanings of words, also offers its users the possibility of including new words or nuancing the meaning of existing words in it. As is understandable, this project would be impossible to carry out without the esteemed collaboration of the people who follow us around the world. This e-Book, therefore, was born with the intention of paying a small tribute to all our collaborators. Alfredo Edgardo Alvarez Ahumada has contributed to the dictionary with 9909 meanings that we have approved and collected in this small book. We hope that the reader is very valuable and if you find it useful or want to be part of the project, do not hesitate to visit our website, we will be delighted to receive you. Working Group www.wordmeaning.org Dictionary of meanings generated by www.wordmeaning.org cazabe CAZABE:OBLEA, BISCUIT OR BREAD WITHOUT YEAST, MADE OF CASSAVA FLOUR. cazador CAZADOR:1. TO HUNT ANIMALS BY DEPORTE.2. DEPREDADOR.3 TRACKER, STALKER. cazalla dry Cazalla:aguardiente, manufactured, or produced in the sierra, province of Seville, Spain. cazoleta CAZOLETA:EMPUNADURA, GUARDIAN, OR OPENING OF A SWORD ON TOP TO PROTECT THE HAND.SPACE OR HOLE IN A PIPE IS PLACED WHERE THE CUT TOBACCO. cazoleteo I cazoleteo: de cazoletear. cucharetear.mover, and removing, removing and putting a spoon in a pot with food. cazonete cazonete: refers to the refrain of wood in the form of tube placed at one end of a cable to carry it, or pass it through a gaza. -

Groundwater Brochure Bhavnagar District

For official use Technical Report Series GROUNDWATER BROCHURE BHAVNAGAR DISTRICT Compiled By SANDEEP VIDYARTHI Scientist – B Government of India Ministry of Water Resources Central Ground Water Board West Central Region Ahmedabad 2013 Profile of Bhavnagar District – Gujarat State Sr No. Particular / Items 1 General Information i. Geographic Area (Sq km) : 9980.9 Sq Km ii. Administrative Units : 11Taluaka – Bhavnagar, Botad, Gadhada, Sihor, Umarana, Gariyadhar, Palitana, Mahuva, Talaja, Ghogha&Vallbhipur iii. No of Villages / Towns :793 Villages ; 10 Statutory Towns and 11 Census Towns. iv. Population ( 2011 Census) : 28,77,961 ; 14,90,465Males&13,87,496Females ; Decennial Growth Rate of population 16.53 % v. Climate : Semi-arid vi. Normal Rainfall : 598.40 mm 2 Physiographic Features i. Physiographic Zones :Coastal marshes ,sandy areas,hilly upland area ,hill ranges,inland Plain & Coastal Plain ii. Drainage :Shetrunji, Ranghola and Kaludhar 3 Agriculture & Irrigation i. Area Reported for Land Use : 857945 ha ii. Gross cropped area: 582001 ha iii. Forest: 26924 ha iv. Irrigation Sources(surface water) a. Canal Network Length : 310.58 km b. Irrigation schemes : 1 major, 14 medium and 53 mino c. Area : 12,9615 ha 4 Geology & Hydrogeology i. Major Geological Formation : Deccan Trap & Alluvium ii. Aquifer System: Both Unconfined & Semi to Confined system in Deccan Trap and Alluvium Formation iii. Groundwater Monitoring : 36 Open wells &12 Piezometers iv. Depth to water level : 1.99 to 30.10 m bgl(Pre monsoon) and 1.37 to 21.76 m bgl (Post monsoon) v. Groundwater Quality : Fresh to saline vi. Groundwater Exploration : Exploration up to 94 m at 67 locations; 42 Exploration Wells ,16 Observation Wells , 9 Piezometers vii. -

COCKTAIL MENU at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, America Was Booming and the Future Was Bright

Drink in the Spirit of Butte. COCKTAIL MENU At the turn of the twentieth century, America was booming and the future was bright. The Industrial Revolution was pushing technology forward, powered by steam and ingenuity. Railroads crossed the continent, connecting people and resources as never before. A network of wires began to weave its way throughout the country, with electric signals and power humming through thousands of miles of copper. In 2010, John and Courtney McKee founded Headframe Spirits in celebration of Butte’s spirit. Standing on the confluence of four lodes of ore, in one of the city’s historic buildings, our company operates with the deepest respect for the history of Butte and the legacy of the mines and the people who worked there. Just as the miners would share an evening together after a hard day’s work, today we share holidays, celebrations and everyday moments with those closest to us. We invite you to share in the joy and appreciate being able to continue our story with you. John & Courtney McKee “The better each of us does, the better we all do together.” To learn more about our story, watch our video from the 'Under The Big Sky Series.’ bit.ly/hfutbs Menu We take our martinis very seriously at Headframe. Please feel free to pick from the High Ore Vodka, Destroying Angel Whiskey or the Anselmo Gin as the base for your martini. If you’re not sure which you’d prefer, ask your bartender for a suggestion. As dirty, or not, as you like. -

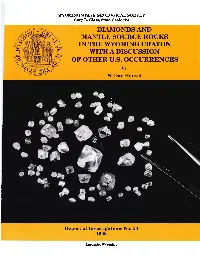

DIAMONDS and MANTLE SOURCE ROCKS in the WYOMING CRATON with a DISCUSSION of OTHER U.S. OCCURRENCES by W

WYOMING STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gary B. Glass, State Geologist DIAMONDS AND MANTLE SOURCE ROCKS IN THE WYOMING CRATON WITH A DISCUSSION OF OTHER U.S. OCCURRENCES by W. Dan Hause} Report of Investigations No. 53 1998 Laramie, Wyoming WYOMING STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Lance Cook, State Geologist GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BOARD Ex Officio Jim Geringer, Governor Randi S. Martinsen, University of Wyoming Don J. Likwartz, Oil and Gas Supervisor Lance Cook, State Geologist Appointed Nancy M. Doelger, Casper Charles M. Love, Rock Springs Ronald A. Baugh, Casper Stephen L. Payne, Casper John E. Trummel, Gillette Computer Services Unit Publications Section Susan McClendon - Manager Richard W. Jones - Editor Jaime R. Bogaard - Editorial Assistant Geologic Sections Lisa J. Alexander - Sales Manager James c. Case, Staff Geologist - Geologic Hazards Fred H . Porter, III - Cartographer Rodney H . De Bruin, Staff Geologist - Oil and Gas Phyllis A. Ranz - Cartographer Ray E. Harris, Staff Geologist - Industrial Minerals Joseph M. Huss - GIS Specialist and Uranium W. Dan Hausel, Senior Economic Geologist - Metals and Precious Stones Supportive Services Unit Robert M. Lyman, Staff Geologist - Coal Susanne G. Bruhnke - Office Manager Alan J. Ver Ploeg, Senior Staff Geologist - Geologic Joan E. Binder - Administrative Assistant Mapping This and other publications available from: Wyoming State Geological Survey P.O. Box 3008 Laramie, WY 82071-3008 Phone: (307) 766-2286 Fax: (307) 766-2605 Email: [email protected] Web Page: http://wsgsweb.uwyo.edu People with disabilities who require an alternative form of communication in order to use this publication should contact the Editor, Wyoming State Geological Survey at (307) 766-2286. TTY Relay operator 1(800) 877-9975.