The Spartan Defeat at Lechaeum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Greek Hoplites and Their Origins

Ancient Greek Hoplites and their Origins By Jordan Wilde Senior Seminar (HST 499W) June 6, 2008 Primary Reader: Dr. Benedict Lowe Secondary Reader: Dr. Lorie Carlson Course Instructor: Dr. David Doellinger History Department Western Oregon University 1 The ancient Greek hoplites were heavily armed infantry soldiers, known for wearing extensive armor, carrying a large rounded shield, spears, and a sword. By looking at armor, weapons, tactics, and vases recovered from archaeological digs, along with literature of the time, such as Homer’s Iliad (ca. 700 B.C.)1 and Hesiod’s Shield of Heracles (ca. end of the late 8th century B.C)2, who and what a hoplite was can be defined. The scholarly consensus has been that eighth century B.C. is crucial in exploring the origins of hoplites. The eighth century sees a dramatic increase in population leading to the rise of city-states and hoplites. In this paper I am going to consider the evidence for the existence of hoplites during the eighth century B.C. and whether or not there is any evidence for their existence before this. When examining evidence for defining when hoplites first appeared, it’s important to understand what makes a hoplite unique, specifically his equipment, weapons, and tactics. In the article “Hoplites and Heresies,” A.J. Holladay looks at the overall view of the hoplite on the battlefield and some forms of military tactics the Greeks might have had. Holladay examines what is typically assumed as hoplite customs, fighting in a close pack, with their shields in their left hand protecting themselves and their neighbors as well as carrying a spear in their right hand. -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

Alexander's Empire

4 Alexander’s Empire MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES EMPIRE BUILDING Alexander the Alexander’s empire extended • Philip II •Alexander Great conquered Persia and Egypt across an area that today consists •Macedonia the Great and extended his empire to the of many nations and diverse • Darius III Indus River in northwest India. cultures. SETTING THE STAGE The Peloponnesian War severely weakened several Greek city-states. This caused a rapid decline in their military and economic power. In the nearby kingdom of Macedonia, King Philip II took note. Philip dreamed of taking control of Greece and then moving against Persia to seize its vast wealth. Philip also hoped to avenge the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 B.C. TAKING NOTES Philip Builds Macedonian Power Outlining Use an outline to organize main ideas The kingdom of Macedonia, located just north of Greece, about the growth of had rough terrain and a cold climate. The Macedonians were Alexander's empire. a hardy people who lived in mountain villages rather than city-states. Most Macedonian nobles thought of themselves Alexander's Empire as Greeks. The Greeks, however, looked down on the I. Philip Builds Macedonian Power Macedonians as uncivilized foreigners who had no great A. philosophers, sculptors, or writers. The Macedonians did have one very B. important resource—their shrewd and fearless kings. II. Alexander Conquers Persia Philip’s Army In 359 B.C., Philip II became king of Macedonia. Though only 23 years old, he quickly proved to be a brilliant general and a ruthless politician. Philip transformed the rugged peasants under his command into a well-trained professional army. -

The Ubiquity of the Cretan Archer in Ancient Warfare

1 ‘You’ll be an archer my son!’ The ubiquity of the Cretan archer in ancient warfare When a contingent of archers is mentioned in the context of Greek and Roman armies, more often than not the culture associated with them is that of Crete. Indeed, when we just have archers mentioned in an army without a specified origin, Cretan archers are commonly assumed to be meant, so ubiquitous with archery and groups of mercenary archers were the Cretans. The Cretans are the most famous, but certainly not the only ‘nation’ associated with a particular fighting style (Rhodian slingers and Thracian peltasts leap to mind but there are others too). The long history of Cretan archers can be seen in the sources – according to some stretching from the First Messenian War right down to the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Even in the reliable historical record we find Cretan archer units from the Peloponnesian War well into the Roman period. Associations with the Bow Crete had had a long association with archery. Several Linear B tablets from Knossos refer to arrow-counts (6,010 on one and 2,630 on another) as well as archers being depicted on seals and mosaics. Diodorus Siculus (5.74.5) recounts the story of Apollo that: ‘as the discoverer of the bow he taught the people of the land all about the use of the bow, this being the reason why the art of archery is especially cultivated by the Cretans and the bow is called “Cretan.” ’ The first reliable references to Cretan archers as a unit, however, which fit with our ideas about developments in ancient warfare, seem to come in the context of the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE). -

The Battlefield Role of the Classical Greek General

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses The battlefield role of the Classical Greek general. Barley, N. D How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Barley, N. D (2012) The battlefield role of the Classical Greek general.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa43080 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Swansea University Prifysgol Abertawe The Battlefield Role of the Classical Greek General N. D. Barley Ph.D. Submitted to the Department of History and Classics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2012 ProQuest Number: 10821472 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Ideals and Pragmatism in Greek Military Thought 490-338 Bc

Roel Konijnendijk IDEALS AND PRAGMATISM IN GREEK MILITARY THOUGHT 490-338 BC PhD Thesis – Ancient History – UCL I, Roel Konijnendijk, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Thesis Abstract This thesis examines the principles that defined the military thinking of the Classical Greek city-states. Its focus is on tactical thought: Greek conceptions of the means, methods, and purpose of engaging the enemy in battle. Through an analysis of historical accounts of battles and campaigns, accompanied by a parallel study of surviving military treatises from the period, it draws a new picture of the tactical options that were available, and of the ideals that lay behind them. It has long been argued that Greek tactics were deliberately primitive, restricted by conventions that prescribed the correct way to fight a battle and limited the extent to which victory could be exploited. Recent reinterpretations of the nature of Greek warfare cast doubt on this view, prompting a reassessment of tactical thought – a subject that revisionist scholars have not yet treated in detail. This study shows that practically all the assumptions of the traditional model are wrong. Tactical thought was constrained chiefly by the extreme vulnerability of the hoplite phalanx, its total lack of training, and the general’s limited capacity for command and control on the battlefield. Greek commanders, however, did not let any moral rules get in the way of possible solutions to these problems. Battle was meant to create an opportunity for the wholesale destruction of the enemy, and any available means were deployed towards that goal. -

Politics and Policy in Corinth 421-336 B.C. Dissertation

POLITICS AND POLICY IN CORINTH 421-336 B.C. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by DONALD KAGAN, B.A., A.M. The Ohio State University 1958 Approved by: Adviser Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREWORD ................................................. 1 CHAPTER I THE LEGACY OF ARCHAIC C O R I N T H ....................7 II CORINTHIAN DIPLOMACY AFTER THE PEACE OF NICIAS . 31 III THE DECLINE OF CORINTHIAN P O W E R .................58 IV REVOLUTION AND UNION WITH ARGOS , ................ 78 V ARISTOCRACY, TYRANNY AND THE END OF CORINTHIAN INDEPENDENCE ............... 100 APPENDIXES .............................................. 135 INDEX OF PERSONAL N A M E S ................................. 143 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................... 145 AUTOBIOGRAPHY ........................................... 149 11 FOREWORD When one considers the important role played by Corinth in Greek affairs from the earliest times to the end of Greek freedom it is remarkable to note the paucity of monographic literature on this key city. This is particular ly true for the classical period wnere the sources are few and scattered. For the archaic period the situation has been somewhat better. One of the first attempts toward the study of Corinthian 1 history was made in 1876 by Ernst Curtius. This brief art icle had no pretensions to a thorough investigation of the subject, merely suggesting lines of inquiry and stressing the importance of numisihatic evidence. A contribution of 2 similar score was undertaken by Erich Wilisch in a brief discussion suggesting some of the problems and possible solutions. This was followed by a second brief discussion 3 by the same author. -

Impact of the Plague in Ancient Greece M.A

Infect Dis Clin N Am 18 (2004) 45–51 Impact of the plague in Ancient Greece M.A. Soupios, EdD, PhD Department of Political Science, Long Island University, C.W. Post Campus, 720 North Boulevard, Brookville, NY 11548, USA The Peloponnesian War is not an isolated incident in the social and military history of ancient Greece. It is better understood as the most spectacular example of a bloody internecine instinct that plagued Hellas throughout most of its history. In the absence of the generalized threat posed by the Great King’s army, the grand alliance that successfully had repulsed the Persian juggernaut in 480 to 479 BC soon began to unravel. Spurred by Athenian adventurism, the Greeks quickly reverted to their traditional jealousies and hatreds. The expansive lusts of Athens convinced Sparta and her allies that the Athenians were a menace to Hellas’ strategic balance of power and that conflict was necessary and inevitable. Formal hostilities commenced in 431 BC and continued intermittently for the next 27 years, during which time much of the luster of the Golden Age of Greece was tarnished irreversibly. War and disease In the 5th century BC, an infantry unit known as the phalanx dominated Greek warfare. This formation was comprised of hoplites, citizen–soldiers who took their name from a large wooden shield (hoplon) that they carried into battle [1]. The killing efficiency of the phalanx had been field-tested thoroughly in the struggles against Persia. In 431 BC, the Greeks redirected their war machine toward fratricidal ends. The Spartans, with their iron discipline and ready willingness to sacrifice all, were the acknowledged masters of this infantry combat. -

Lecture 17 Spartan Hegemony and the Persian Hydra

3/15/2012 Lecture 17 Spartan Hegemony and the Persian Hydra HIST 332 Spring 2012 The Aftermath of the Peloponnesian War • General – Greece in a state of economic and demographic devastation; proliferation of mercenaries. • Athens - starved into submission: – Demolish the Long Walls – Surrender all ships except 12 – Accept the lead of Sparta – An oligarchic government by 30 men is put in place by Lysander – Democracy is abolished • Rule of the Thirty Tyrants • Ionian Greeks – Under Persian control. • Sparta –hegemon of Greece; – imposes harmosts & garrisons on defeated cities – allied to the Persians. 4th century Greece Period of continuous warfare • The Corinthian War (394-386 BCE). • Thebes and Sparta (377-362 BCE). • The Social War (357-355 BCE). • The hegemony of Macedon. 1 3/15/2012 Spartan general Lysander Probably of noble descent but impoverished • Lover of prince Agesilaos • Ambitious and Un-Spartan in some ways: – understood way to defeat Athens was to create a navy – He created a bond with the Persian prince Cyrus, son of king Darius II • funded the Spartan fleet • Power-hungry – not enough to stage open revolt against the Spartan constitution Agesilaos II (401-360) A towering figure in Spartan history • Eurypontid king when Sparta ruled Greek world – Half-brother of king Agis II • Very popular among the men in the army, very influential – He had undergone the agoge despite his lame leg – hated Thebes • influenced many wrong decisions – largely responsible for the decline of Spartan power – impoverish the Spartan treasury • -

In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Ancient Macedonia

Advance press kit Exhibition From October 13, 2011 to January 16, 2012 Napoleon Hall In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Ancient Macedonia Contents Press release page 3 Map of main sites page 9 Exhibition walk-through page 10 Images available for the press page 12 Press release In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Exhibition Ancient Macedonia October 13, 2011–January 16, 2012 Napoleon Hall This exhibition curated by a Greek and French team of specialists brings together five hundred works tracing the history of ancient Macedonia from the fifteenth century B.C. up to the Roman Empire. Visitors are invited to explore the rich artistic heritage of northern Greece, many of whose treasures are still little known to the general public, due to the relatively recent nature of archaeological discoveries in this area. It was not until 1977, when several royal sepulchral monuments were unearthed at Vergina, among them the unopened tomb of Philip II, Alexander the Great’s father, that the full archaeological potential of this region was realized. Further excavations at this prestigious site, now identified with Aegae, the first capital of ancient Macedonia, resulted in a number of other important discoveries, including a puzzling burial site revealed in 2008, which will in all likelihood entail revisions in our knowledge of ancient history. With shrewd political skill, ancient Macedonia’s rulers, of whom Alexander the Great remains the best known, orchestrated the rise of Macedon from a small kingdom into one which came to dominate the entire Hellenic world, before defeating the Persian Empire and conquering lands as far away as India. -

Phalanxes and Triremes: Warfare in Ancient Greece by Ancient History Encyclopedia, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 08.08.17 Word Count 1,730 Level 1230L

Phalanxes and Triremes: Warfare in Ancient Greece By Ancient History Encyclopedia, adapted by Newsela staff on 08.08.17 Word Count 1,730 Level 1230L A lithograph plate showing ancient Greek warriors in a variety of different uniforms. Photo from Wikimedia. In the ancient Greek world, warfare was seen as a necessary evil of the human condition. Whether it be small frontier skirmishes between neighboring city-states, lengthy city-sieges, civil wars or large-scale battles between multi-alliance blocks on land and sea, the vast rewards of war were thought to outweigh the costs in material and lives. While there were lengthy periods of peace, the desire for new territory, war booty or revenge meant the Greeks were regularly engaged in warfare both at home and abroad. Toward professional warfare The Greeks did not always have professional soldiers. Warfare started out as the business of private individuals. Armed bands led by warrior leaders, city militias of part-time soldiers provided their own equipment and may have included all the citizens of the city-state. Eventually, the conduct of warfare started to move away from private individuals and into the realm of the state. This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. In the early stages of Greek warfare in the Archaic period, training was haphazard. There were no uniforms or insignia and as soon as the conflict was over the soldiers would return to their farms. By the fifth century B.C, the military might of Sparta provided a model for all other states to follow. -

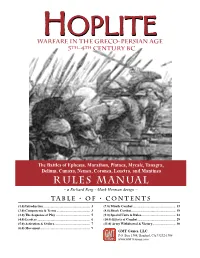

Rules Manual ~ a Richard Berg - Mark Herman Design ~ Table • of • Contents (1.0) Introduction

Warfare in the Greco-Persian Age 5th-4th Century BC The Battles of Ephesus, Marathon, Plataea, Mycale, Tanagra, Delium, Cunaxa, Nemea, Coronea, Leuctra, and Mantinea Rules Manual ~ a Richard Berg - Mark Herman design ~ Table • of • Contents (1.0) Introduction ......................................................... 3 (7.0) Missile Combat .................................................... 15 (2.0) Components & Terms ......................................... 3 (8.0) Shock Combat ...................................................... 18 (3.0) The Sequence of Play .......................................... 5 (9.0) Special Units & Rules .......................................... 24 (4.0) Leaders ................................................................. 6 (10.0) Effects of Combat .............................................. 28 (5.0) Activation & Orders ............................................ 7 (11.0) Army Withdrawal & Victory ............................ 30 (6.0) Movement ............................................................. 9 GMT Games, LLC P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 www.GMTGames.com 2 Hoplite ~ Rules of Play (2.0) Components & Terms Each Game of Hoplite contains: 3 22" x 34” mapsheets, backprinted 4 Sheets of game pieces (units & markers) (1.0) Introduction 1 Rules Booklet Hoplite (HOP), the 15th volume in the Great Battles of His- 1 Scenario Booklet tory series of games, allows players to recreate classic battles 6 17" x 11" Player Aid cards (two of each) from the pre-Alexandrian Greco-Persian Age, the