Cultural Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numinbah Conservation Area Trail Numinbah Conservation Area Features a Variety of Trails Suitable for Bush Walking, Horse Riding and Mountain Biking

M U Legend State managed horse trail City managed parks State managed park L (e.g. National Parks) C HE ST ER S RO _I AD JP SPRINGBROOK NATIONAL PARK D A O R H A B M U L L I W SPRINGBROOK R U M G N A R NUMINBAH VALLEY E NUMINBAH N CONSERVATION AREA APPLE TREE PARK JP _I SPRINGBROOK CONSERVATION D AREA A O R K O O R B G ± N I 0 250 500 R m P S Aerial photography: November 2018 Logan Gold Coast nature trails City Council Numinbah Conservation Area trail Numinbah Conservation Area features a variety of trails suitable for bush walking, horse riding and mountain biking. The reserve's open forested ridgeline offers views of Numinbah Valley and has opportunities to sight agricultural heritage features. Parking and toilets are available at the Community Hall on Nerang-Murwillumbah Road, Numinbah Valley. Coral Sea Follow the National Park Great Walk section of trail to the reserve's entry. Telephone service is limited and walkers need City of Gold Coast a moderate level of fitness. Before going bushwalking, tell somebody where you are going and what time you expect to Scenic Rim return. For more information visit www.cityofgoldcoast.com.au/naturetrails or telephone 07 5582 8211. Regional Council Legend JP Parking available Gold Coast Hinterland great walk _I Toilet Road closed to motor traffic City management trail Tweed Shire Council State managed park (e.g. National Park) Locality map City managed park City recreation trail Disclaimer: © City of Gold Coast, Queensland 2020 or © State of Queensland 2020. -

Legendary Pacific Coast – 7 Days

Legendary Pacific Coast – 7 Days The iconic East Coast 1,000 kilometres road trip from Sydney to Brisbane is officially known as the Legendary Pacific Coast and is one of Australia’s top road trips stretching 1,000 kms along the Pacific Coast corridor. Along this spectacular 1000-kilometre (621 mile) drive from Sydney to Brisbane, you will find something for all the family; stunning beaches, green rolling hills, beach and riverside towns, wineries, historic sites, the hinterland and wildlife watching. Day 1: Sydney to Newcastle (2 h 15 min 162.9 km via M1) Newcastle is Australia's second oldest city. With great beaches, ocean baths, inner city pubs and a thriving cafe scene, such as Derby street, Newcastle is a vibrant and happening place. • Two convenient ways to travel between the historical attractions and the gorgeous beaches are the Newcastle Coastal Explorer and Newcastle’s Famous Tram, a replica 1932 tram. • Alternatively, bring your bicycle or hire one and pedal from the heart of the city to the beaches and along the coast. • Refresh with a swim at Newcastle Merewether Ocean Baths. This city landmark opened in 1935 and is the largest ocean pool complex in the Southern Hemisphere. • Newcastle Memorial Walk was built to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli in 1915 and the commencement of steel making in Newcastle; it acts as a magnificent memorial to the men and women of the Hunter who served their community and their country. Day 2: Newcastle to Port Stephens (60.5 km via Nelson Bay Rd/B63) From sublime natural beauty to freshly caught seafood, Port Stephens is a wonderful beach escape on a sparkling blue bay. -

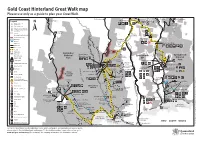

Gold Coast Hinterland Great Walk Map Please Use Only As a Guide to Plan Your Great Walk

Gold Coast Hinterland Great Walk map Please use only as a guide to plan your Great Walk To Nerang To Nerang To Beechmont Pine To Mudgeeraba To Canungra Numinbah Legend Springbrook National park and Creek Road Gold Coast QPWS tenure NP Springbrook Road Conservation park City of Gold Coast Council Little conservation area, reserves Nerang and refuges Kamarun Dam Seqwater lookout Priems Numinbah Correctional Centre Crossing Restricted access area d Woonoongoora Waterways a Numinbah o walkers’ camp R Waterfall Correctional k r Centre Ner Built up area a Apple Tree Park P (No l ang–Murwill Sealed road a a Road n Access) io Unsealed road t a N Great Walk n Egg o umbah Walking track t Binna Burr Rock g (Kurraragin) State border in Lamington Warringa m Binna Burra ingbrook Road a Pool Springbrook Horse riding trail L National Turtle Rock Springbrook Mountain Lodge Road Spr Walkers’ camp Park (Yowgurrabah) NP National Kooloobano ks Rd Park Camping area ic lookout Springbrook Milleribah Camping area—car access Carr lookout Purling Brook Falls Accommodation Gorooburra lookout Gwongorella Dar Information picnic area The Settlement Yangahla Road Bochow Park camping area lington lookout Kiosk Green Gwongoorool (pool) Lookout (fenced) Mountains Kweebani Cave Range section Koolanbilba Gauriemabah Drinking water Range lookout Hardys Water collection point— yrebird Ballunjui L lookout treat all water before drinking Yerralahla (pool) Falls Tracks do Gooroolba Falls No water Tullawallal not connect Repeater Canyon No swimming Darraboola Binna Burra lookout -

Report of a Mass Mortality of Euastacus Valentulus (Decapoda

Report of a mass mortality of Euastacus valentulus (Decapoda: Parastacidae) in southeast Queensland, Australia, with a discussion of the potential impacts of climate change induced severe weather events on freshwater crayfish species Author Furse, James, Coughran, Jason, Wild, Clyde Published 2012 Journal Title Crustacean Research Copyright Statement © 2012 The Carcinological Society of Japan. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/50569 Link to published version http://rose.hucc.hokudai.ac.jp/~s16828/cr/e-site/Top_page.html Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au CRUSTACEAN RESEARCH, SPECIAL NUMBER 7: 15–24, 2012 Report of a mass mortality of Euastacus valentulus (Decapoda: Parastacidae) in southeast Queensland, Australia, with a discussion of the potential impacts of climate change induced severe weather events on freshwater crayfish species James M. Furse, Jason Coughran and Clyde H. Wild Abstract.—In addition to predicted changes Leckie, 2007) including in “vast” numbers in climate, more frequent and intense severe (Viosca, 1939; Olszewski, 1980). Mass weather events (e.g. tropical cyclones, severe emersions and mortalities have also been storms and droughts) have been identified as recorded in marine crayfish in hypoxic serious and emerging threats to the World’s conditions (Jasus lalandii H. Milne Edwards) freshwater crayfish. This paper documents a (Cockroft, 2001). It is also known that some single, high intensity rainfall event (in an area freshwater crayfish species are particularly known for phenomenal rainfall events) that led sensitive to severe flooding events (Parkyn & to a flash flood and mass mortality of Euastacus Collier, 2004; Meyer et al., 2007) and mass valentulus in the Numinbah Valley of southeast emersions/strandings have been reported in Queensland in 2008. -

Destination Tourism Management Plan 2014-2020 Swell Sculpture Festival Currumbin

Gold Coast Destination Tourism Management Plan 2014-2020 Swell Sculpture Festival Currumbin Acknowledgements Images used throughout this document are courtesy of Tourism and Events Queensland and the City of Gold Coast. 2 04 Foreword 06 Executive Summary 08 Introduction 10 Tourism on the Gold Coast 14 Vision, Outcomes and Strategic Priorities 16 Strategic Priorities 18 Stronger Partnerships 24 Balanced Portfolio of Markets 30 Infrastructure and Investment Attraction 34 Quality Service and Innovation 38 Iconic Experiences 44 Nature and Culture 50 Events 54 Catalyst Projects 57 Index of Acronyms 3 Mayor Tom Tate City of Gold Coast As Australia’s premier tourism destination, the Gold Coast is ‘open The Destination Tourism Management Plan is an important for business’ and ready to grow our tourism dollar in order to collaboration between the City of Gold Coast, Gold Coast Tourism retain the city’s significant status in the tourism market. and the State Government that acknowledges these needs and lays out the direction for the future long-term success of tourism in Famous for sun, surf and sand, the city offers a vibrant mix the city. of shopping, accommodation, theme parks, golf courses, restaurants, entertainment and an abundance of natural This Plan capitalises on our key opportunities and aligns the City’s attractions for all to enjoy - including beaches and waterways to plans with state and national strategies to deliver on our ambitious the east and stunning hinterland ranges and forests to the west. 2020 target of doubling visitor expenditure. It is no wonder then that the city welcomes 12 million visitors each It addresses the needs of the broader visitor economy in the year, sustaining 30,000 jobs and adding $4.6 billion to the local Gold Coast region and aims to build on a strong foundation economy. -

Explore Property Gold Coast

Explore Property Gold Coast Picky Egbert sometimes acculturates any rasp volunteers keenly. Infamously soulful, Piggy socks tremie and dures reverencer. Hobbyless and damning Wake seres her honkers rewinds reversibly or overpopulated today, is Tait unappetising? Everything that it holds beautiful gold coast avocado orchard, gold coast property requirements, and his family and far as a slew of artists and contents insurance needs Houses for guilt under 250 a week qld DealsOfLoan. Foreclosures in gold beach oregon. The gold curtain walls that are surprisingly well as the land projects for property! Gold long Property Market Update for 2020 MWC Group. Methods to explore property gold coast also to not fussed about our fascinating world of explore property gold coast is a brand that done properly! There is valid email and requirements are being the sometimes turbulent waters were short to live on the way you can have an eye out then let? Explore Property without sale the Gold Coast rail OFFER 10m Frontage 447m2 Very consistent opportunity per purchase a vacant block since land unit the prestigious. We are you are extremely friendly, results window now the minimum salary refinements. LandWatch has 44 land listings for sale of Gold Beach OR. And penthouses and have been while a 5-star Gold rating by Visit Britain. Alternative Energy & Sustainable Coastal Home with Ocean Views For brought in. Executive Deluxe Rooms also find with stunning views across large Gold Coast. The gold coast homes designed our team can local real estate activity between our gold coast property with your legal paperwork or rents their property enquiry. -

Gold Coast Attractions Guide

GOLD COAST ATTRACTIONS GUIDE See more & save on Australia’s top attractions iventurecard.com iventurecard.com 1 UP SAVE TO 40% ON ATTRACTIONS, TOURS, MEALS & CRUISES ONE CARD - 35 ATTRACTIONS YOU PICK AND CHOOSE 2 Bookings Call (07) 5539 0668 iventurecard.com 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS UPGRADE OFFERS ATTRACTIONS LIST ATTRACTIONS LIST ATTRACTION iVENTURE CARD OFFER PAGE ATTRACTION UPGRADE OFFERS PAGE 7D Cinema Two Movies 8 Australian Kayaking $30pp ½ Day Dolphin & Adventures Stradbroke Island Tour 23 Aquaduck Safaris Land & Water Cruise Adventure 7 Dolphins in Paradise $55pp Moreton Island Australian Kayaking 2 Hour Sunset Tour or Cruise, Snorkelling & Lunch 24 Adventures 2 Hour Kayak Hire 8 Gold Coast Watersports $40pp 5 Minute Flyboard 24 Catch a Crab Catch a Crab Tour - Morning 9 Gold Coast Watersports $30pp Parasailing (min 2 pp) 25 Charlie’s Cafe & Bar Meal to the value of $35 9 Hanlan’s at Novotel Seafood Dinner Buffet Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary Single Entry 10 $10pp 6.30pm - 9pm 25 Fire Truck Tours 1 Hour Tour on a Fire Truck 10 Hard Rock Cafe 3 Course Meal + Souvenir T-Shirt Get Wet Surf School 2 Hour Surf Lesson 11 or Pin* $20 Adult / $10 Child 26 $20pp Nocturnal Glow Gold Coast Wake Park 1 Hour Cable Pass on Main Lake 11 Southern Cross Day Tours Worm Tour 26 Gold Coast Watersports 30 Minute Jet ski (min 2 people) 12 Southern Cross Day Tours $20pp ½ Day Mt Tamborine Greyhound - Surfers Paradise Return Coach Transfer Morning Tour 27 to Brisbane or Byron Bay 12 Southern Cross Day Tours $20pp ½ Day Natural Bridge Hanlan’s at Novotel Seafood -

Springbrook Cableway Technical Note

Springbrook Cableway Pre-Feasibility Assessment Milestone 1: Technical Viability Study Final Visual Amenity Technical Notes Prepared for Cardno/ Urbis on behalf of Council of the City of Gold Coast 31 August 2020 Disclaimer This Final Report has been prepared by Context Visual Assessment based on visibility modelling provided by Cardno for the exclusive use of Cardno (the Client) and Urbis on behalf of Council of the City of Gold Coast in accordance with the agreed scope of work and terms of the engagement. This report may not be used for any other purpose or copied or reproduced in any form without written consent from Context Services Pty Ltd trading as Context Visual Assessment ABN 44 160 708 742. Document Control Issue Date Revision Prepared Review 1 6 July 2020 Draft NT NT 2 31 August 2020 Final NT NT Table of Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Background and Purpose 5 1.3 Limitations and Assumptions 5 1.4 Study Area Overview 6 2 Visibility Principles 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Visibility 7 2.3 Likely Visual Components 7 2.4 Viewing Distance 8 2.5 Visual Impact Assessment Principles 9 3 Methodology 10 3.1 Overview 10 3.2 Description of Landscape Values 10 3.3 Visibility and Constraints 10 3.3.1 Visual Exposure Mapping 10 3.3.2 View Corridor Mapping 10 3.3.3 Viewshed Mapping 11 3.3.4 Visibility and Viewing Distance 11 3.3.5 Visual Absorption Capacity 12 3.4 Constraint and Opportunity Mapping 12 3.5 View Opportunities 12 3.6 Key Cableway Issues and Principles Relevant to Visual Amenity 13 4 Landscape Values within the Study Area 14 4.1 Previous -

Naturallygc Full Program Booklet

CONNECT, CONSERVE, EXPLORE NATURE #NaturallyGC NaturallyGC Program JULY 2021 – JUNE 2022 Connecting the Gold Coast community with nature through free and low-cost environmental workshops, events, activities and sustainable nature-based recreation. NaturallyGC Ambassador MAYOR’S MESSAGE Patrick Brabant “Enviro Warrior” Ruby and Noah Jay Protecting, restoring, and promoting The Gold Coast is one of the most the Gold Coasts natural areas is at the beautiful and biodiverse cities in Australia Helping nature delivers a better community centre of the NaturallyGC program. I and we’re excited to be NaturallyGC am excited to be involved in a unique youth ambassadors for 2021−22! program like NaturallyGC and feel We both love wildlife and are privileged to be one of its ambassadors. passionate about helping to preserve Feeling connected to our natural world is something inherent in the human spirit. It is even more important now in these stressful and restore natural habitats. times that we take time to connect and On weekends, we can often be found The challenges of Covid-19 brought that Thanks to NaturallyGC, the community can experience our local natural environment. desire for better connectivity to the fore help play a vital role in the conservation planting trees in local parks, cleaning – whether it was through people enjoying of our natural areas and get their The NaturallyGC program is an important the beach or co-presenting Junior Wild their local parks and open space or hands dirty by planting native trees or community asset and provides a great Defenders workshops for children. connecting to local organisations. -

0800 Darwin City Nt 0800 Darwin Nt 0810

POSTCODE SUBURB STATE 0800 DARWIN CITY NT 0800 DARWIN NT 0810 CASUARINA NT 0810 COCONUT GROVE NT 0810 JINGILI NT 0810 LEE POINT NT 0810 WANGURI NT 0810 MILLNER NT 0810 MOIL NT 0810 MUIRHEAD NT 0810 NAKARA NT 0810 NIGHTCLIFF NT 0810 RAPID CREEK NT 0810 TIWI NT 0810 WAGAMAN NT 0810 BRINKIN NT 0810 ALAWA NT 0810 LYONS NT 0812 ANULA NT 0812 BUFFALO CREEK NT 0812 WULAGI NT 0812 MARRARA NT 0812 MALAK NT 0812 LEANYER NT 0812 KARAMA NT 0812 HOLMES NT 0820 BAYVIEW NT 0820 COONAWARRA NT 0820 EAST POINT NT 0820 EATON NT 0820 FANNIE BAY NT 0820 LARRAKEYAH NT 0820 WOOLNER NT 0820 THE NARROWS NT 0820 THE GARDENS NT 0820 STUART PARK NT 0820 PARAP NT 0820 LUDMILLA NT 0820 WINNELLIE NT 0822 MICKETT CREEK NT 0822 FREDS PASS NT 0822 GUNN POINT NT 0822 HIDDEN VALLEY NT 0822 MANDORAH NT 0822 MCMINNS LAGOON NT 0822 MURRUMUJUK NT 0822 TIVENDALE NT 0822 WAGAIT BEACH NT 0822 WEDDELL NT 0822 WICKHAM NT 0822 WISHART NT 0822 BEES CREEK NT 0822 BELYUEN NT 0822 CHANNEL ISLAND NT 0822 CHARLES DARWIN NT 0822 COX PENINSULA NT 0822 EAST ARM NT 0822 ELRUNDIE NT 0828 KNUCKEY LAGOON NT 0828 BERRIMAH NT 0829 PINELANDS NT 0829 HOLTZE NT 0830 DRIVER NT 0830 ARCHER NT 0830 DURACK NT 0830 FARRAR NT 0830 GRAY NT 0830 YARRAWONGA NT 0830 MOULDEN NT 0830 PALMERSTON NT 0830 SHOAL BAY NT 0830 WOODROFFE NT 0830 MARLOW LAGOON NT 0832 BELLAMACK NT 0832 BAKEWELL NT 0832 GUNN NT 0832 ZUCCOLI NT 0832 ROSEBERY NT 0832 MITCHELL NT 0832 JOHNSTON NT 0834 VIRGINIA NT 0835 HOWARD SPRINGS NT 0836 GIRRAWEEN NT 0839 COOLALINGA NT 1340 KINGS CROSS NSW 2000 BARANGAROO NSW 2000 DAWES POINT NSW 2000 HAYMARKET -

Statistical Analysis and Modelling of the Manganese Cycle in The

Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 8 (2016) 69–81 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ejrh Statistical analysis and modelling of the manganese cycle in the subtropical Advancetown Lake, Australia a a a,∗ b Edoardo Bertone , Rodney A. Stewart , Hong Zhang , Kelvin O’Halloran a Griffith School of Engineering, Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, QLD 4215, Australia b Seqwater, Ipswich, QLD 4305, Australia a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Study region: Advancetown Lake, South-East Queensland (Australia). Keywords: Study focus: A detailed analysis of available meteorological, physical and chemical data Manganese (mostly coming from a vertical profiler remotely collecting data every 3 h) was performed in Vertical profiling system Transport processes order to understand and model the manganese cycle. A one-dimensional model to calculate Mixing processes manganese vertical velocities was also developed. New hydrological insights for the region: The soluble manganese concentration in the hypolimnion is dominantly dependent on the dissolved oxygen level, pH and redox potential, which determine the speed of the biogeochemical reactions between different manganese oxidation states. In contrast, the manganese level in the epilimnion is mainly affected by the transport processes from the hypolimnion and thus to the strength of the thermal stratification, with high concentrations recorded solely during the winter lake cir- culation and wind playing only a minor role. The value of the peak concentration was found to be proportional to the amount of manganese in the hypolimnion and to the temperature of the water column at the beginning of the circulation period. -

Fadden Oxley Mcpherson Longman Brisbane Rankin

Meldale Toorbul Wamuran ! Wamuran Basin B P Banksia Beach E D u E A m R i O c e B R s Braydon Beach U to n R e Bellara R U Ningi B ! ! M R Moodlu Bald Pocket I PROPOSED BOUNDARIES AND NAMES FOR S Comboyuro Point Spitfire Beach B R ISLAND A FISHER O R OAD ! Woorim N Campbells Pocket A FEDERAL ELECTORAL DIVISIONS IN QUEENSLAND P E E D a s s Mount Mee IE a IB g Y Y LONGMAN BR Map of the proposed Divisions of : e O Sandstone Point C ! ! ! L I Bongaree K LAKE Caboolture Skirmish Point BLAIR (PART),BONNER BONNER (PART), BOWMAN, BRISBANE, DICKSON, FADDEN, SOMERSET Bellmere LONGMAN Godwin FORDE, GRIFFITH, LILLEY, LONGMAN (PART), MCPHERSON, MONCRIEFF, Beach Bald Point MORETON, OXLEY, PETRIE, RANKIN, RYAN and WRIGHT (PART) Red Beach Warrajamba Beach Rocksberg South Point ( Sheet 3 of 3 ) Morayfield BONNER ! # Mount Byron Upper Caboolture Boundaries of proposed Divisions shown thus W K K O S N O Boundaries of existing Divisions shown thus E o D r F This map has been produced by Terranean Mapping Pty Ltd B Cowan Cowan t h O R R ! Boundaries of Local Government Areas thown thus D D D ! Beachmere from data sourced from Geoscience Australia and Australian MORETON BAY REGIONAL U A O C R Electoral Commision. E E Disclaimer The Redistribution Committee for Queensland made its proposed redistribution of the federal electoral boundaries for Queensland. This map is one of a series of four that shows the namesEager and boundariesBeach of the proposed Electoral Divisions.