Wayfinding & Dementia: How Design Can Improve Navigation Among

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

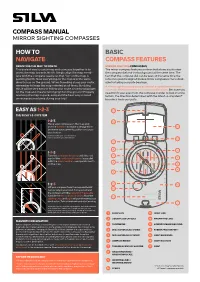

Silva Manual- Mirror Sighting Compasses

COMPASSHOW MANUAL TO MIRROR SIGHTING COMPASSES NAVIGATEHOW TO BASIC NAVIGATE COMPASS FEATURES HOWORIENTING TO THE MAP TO NORTH MIRROR SIGHTING COMPASSES EASYThe easiest way to use a map and compass AS together is to The mirror compass features a mirror that allows you to view orient the map towards North. Simply align the map merid- the compass dial and the background at the same time. The ians with the compass needle so that “up” on the map is fact that the compass dial can be seen at the same time the pointing North. Now everything on the map is in the same reference point is aligned makes mirror compasses more desir- NAVIGATEdirection as on the ground. When travelling along your route, able for taking accurate bearings. remember to keep the map oriented at all times. By doing A mirror-sighting compass is at its best in open terrain where 1-2-3this it will be very easy to follow your route since turning right you must determine direction over long distances. Because you on the map also means turning right on the ground! Properly needn’t lift your eyes from the compass in order to look into the orienting1-2-3 the map is quick, easy1-2 and-3 the best way to avoid1-2- 3 terrain, the direction determined with the Silva 1-2-3 System® HOW TOunnecessaryPlace your compass mistakes on the map duringTurn your the compass trip! housing until the Lift your compass frombecomes the map more accurate. and use the baseline to make a red part of the north/south arrow and hold it horizontally in your EASYstraight line between AS your current is parallel with the map meridians, hand. -

Environmental Geocaching: Learning Through Nature and Technology

WSFNR-20-67A September 2020 ENVIRONMENTAL GEOCACHING: LEARNING THROUGH NATURE AND TECHNOLOGY Brady Self, Associate Extension Professor, Department of Forestry, Mississippi State University Jason Gordon, Assistant Professor, Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia Parents, natural resource professionals and enthusiasts, and youth coordinators often find themselves at a loss when trying to encour- age younger generations to take up outdoor pastimes. The allure of electronic technology, team sports, combined with time availability of parents sometimes limits overall involve- ment of today’s youth in more traditional outdoor activities. In this fast-paced world, learning about nature and what occurs in the forest seems to be losing ground when competing for adolescents’ interest and time. The good news is that there are still many op- portunities to involve youth in the outdoors. The game of geocaching provides one of these opportunities. Geocaching offers learning and fun while spending time in nature. Geocaching is an outdoor treasure hunting game that operates much like the scavenger hunting that many parents and grandparents remember from their youth. The game adds the use of GPS technology (either a dedi- cated receiver unit, or more commonly, a GPS-enabled smartphone) to guide players to locations where individual geocaches are hidden. Clues are then used to search for the geocache. Geocaches can be selected or created with a theme focused on learning about forests, wildlife, and other natural resources. These experiences are then shared online in the geocaching community. The overall objective of the activity is to guide participants to places of significance where they have the opportu- nity to learn something about that particular location or geocache topic. -

Autonomous Geocaching: Navigation and Goal Finding in Outdoor Domains

Autonomous Geocaching: Navigation and Goal Finding in Outdoor Domains James Neufeld Jason Roberts Stephen Walsh University of Alberta University of Alberta University of Alberta 114 St - 89 Ave 114 St - 89 Ave 114 St - 89 Ave Edmonton, Alberta Edmonton, Alberta Edmonton, Alberta [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Michael Sokolsky Adam Milstein Michael Bowling University of Alberta University of Waterloo University of Alberta 114 St - 89 Ave 200 University Avenue West 114 St - 89 Ave Edmonton, Alberta Waterloo, Ontario Edmonton, Alberta [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT ticipants use a handheld GPS to aid in ¯nding an object This paper describes an autonomous robot system designed hidden in an unknown environment given only the object's to solve the challenging task of geocaching. Geocaching GPS coordinates. Typically the objects are placed in unde- involves locating a goal object in an outdoor environment veloped areas with no obvious roads or paths. Natural ob- given only its rough GPS position. No additional informa- stacles along with the lack of any map of the terrain make tion about the environment such as road maps, waypoints, it a challenging navigation problem even for humans. In ad- or obstacle descriptions is provided, nor is there often a sim- dition, due to the error in GPS position estimates, a search ple straight line path to the object. This is in contrast to is usually required to ¯nally locate the object even after the much of the research in robot navigation which often focuses GPS coordinate has been reached. -

Military Map Reading V2.0

MILITARY MAP READING This booklet is to help qualified Defence Map Reading instructors in unit map reading training and testing. The primary source is the Manual of Map Reading and Land Navigation, Army Code 71874.Issue 1.0: Apr 2009. The booklet can be used by all ranks of HM Forces (RN, RM, Army and RAF) for study and revision. It is suggested that a map of the local area be obtained for practical work and for the study of Conventional signs, which are intentionally NOT covered in this booklet. Comments and queries should be addressed to: Senior Instructor, Geospatial Information Management Wing Royal School of Military Survey, Defence Intelligence Security Centre, Denison Barracks (SU 498 729) Hermitage, THATCHAM, Berkshire, RG18 9TP © Crown copyright. All rights reserved ICG 100015347 2007 Version 2.0 Dated December 2010. 1 MILITARY MAP READING INDEX CHAPTER 1: MAP READING FUNDAMENTALS Maps and the grid system 3 Grid references 3 MGRS 5 Romers 6 GPS 7 Scale 8 Estimating and measuring distances 9 Contours 11 The shape of the ground 12 Bearings 15 Compass distances from ferrous metal 17 CHAPTER 2: NAVIGATION EQUIPMENT The compass LW 18 The prismatic compass 20 The RA protractor 22 CHAPTER 3: TECHNIQUES AND SKILLS Relating map and ground 24 Using a lightweight compass to set a map 26 Finding a location by LW Intersection 27 Plotting back bearings-LW/RA protractor 28 Finding your location by LW resection 29 Finding direction by sun and stars 30 CHAPTER 4: ROUTE SELECTION Factors for route selection 34 Other planning factors 35 Route cards -

A Cognitive Model of Strategies for Cardinal Direction Judgments

SPATIAL COGNITION AND COMPUTATION, 7(2), 179–212 Copyright © 2007, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. A Cognitive Model of Strategies for Cardinal Direction Judgments Leo Gugerty and William Rodes Psychology Department, Clemson University, Clemson, SC ABSTRACT Previous research has identified a variety of strategies used by novice and experienced navigators in making cardinal direction judgments (Gugerty, Brooks, & Treadaway, 2004). We developed an ACT-R cognitive model of some of these strategies that instantiated a number of concepts from research in spatial cognition, including a visual-short-term-memory buffer overlaid on a perceptual buffer, an egocentric ref- erence frame in visual-short-term-memory, storage of categorical spatial information in visual-short-term-memory, and rotation of a mental compass in visual-short-term- memory. Response times predicted by the model fit well with the data of two groups, college students (N D 20) trained and practiced in the modeled strategies, and jet pilots (N D 4) with no strategy training. Thus, the cognitive model seems to pro- vide an accurate description of important strategies for cardinal direction judgments. Additionally, it demonstrates how theoretical constructs in spatial cognition can be applied to a complex, realistic navigation task. Keywords: cardinal directions, cognitive modeling, visual short term memory. INTRODUCTION This project focuses on understanding the cognitive processes and structures people use in making a particular type of navigational judgment—using a map to determine the cardinal direction between two objects in the environment. We first developed a cognitive model of some of the strategies people use in making this type of cardinal direction judgment. -

Land Navigation, Compass Skills & Orienteering = Pathfinding

LAND NAVIGATION, COMPASS SKILLS & ORIENTEERING = PATHFINDING TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. LAND NAVIGATION, COMPASS SKILLS & ORIENTEERING-------------------p2 1.1 FIRST AID 1.2 MAKE A PLAN 1.3 WHERE ARE YOU NOW & WHERE DO YOU WANT TO GO? 1.4 WHAT IS ORIENTEERING? What is LAND NAVIGATION? WHAT IS PATHFINDING? 1.5 LOOK AROUND YOU WHAT DO YOU SEE? 1.6 THE TOOLS IN THE TOOLBOX MAP & COMPASS PLUS A FEW NICE THINGS 2 HOW TO USE A COMPASS-------------------------------------------p4 2.1 2.2 PARTS OF A COMPASS 2.3 COMPASS DIRECTIONS 2.4 HOW TO USE A COMPASS 2.5 TAKING A BEARING & FOLLOWING IT 3 TOPOGRAPHIC MAP THE BASICS OF MAP READING---------------------p8 3.1 TERRAIN FEATURES- 3.2 CONTOUR LINES & ELEVATION 3.3 TOPO MAP SYMBOLS & COLORS 3.4 SCALE & DISTANCE MEASURING ON A MAP 3.5 HOW TO ORIENT A MAP 3.6 DECLINATION 3.7 SUMMARY OF COMPASS USES & TIPS FOR USING A COMPASS 4 DIFFERENT TYPES OF MAPS----------------------------------------p13 4.1 PLANIMETRIC 4.2 PICTORIAL 4.3 TOPOGRAPHIC(USGS, FOREST SERVICE & NATIONAL PARK) 4.4 ORIENTIEERING MAP 4.5 WHERE TO GET MAPS ON THE INTERNET 4.6 HOW TO MAKE YOUR OWN ORIENTEERING MAP 5 LAND NAVIGATION & ORIENTEERING--------------------------------p14 5.1 WHAT IS ORIENTEERING? 5.2 Orienteering as a sport 5.3 ORIENTEERING SYMBOLS 5.4 ORIENTERING VOCABULARY 6 ORIENTEERING-------------------------------------------------p17 6.1 CHOOSING YOUR COURSE COURSE LEVELS 6.2 DOING YOUR COURSE 6.3 CONTROL DESCRIPTION CARDS 6.4 CONTROL DESCRIPTIONS 6.5 GPS A TOOL OR A CRUTCH? 7 THINGS TO REMEMBER-------------------------------------------p22 -

Door to Door Navigation App from Google Play Or the Apple App Store

DOOR TO DOORDOOR NAVIGATION NAVIGATIONQUICK START GUIDE QUICK START GUIDE GO WITH CONFIDENCE GETTING STARTED Congratulations. Your new Nissan vehicle comes with a built-in navigation system that guides you door to door from one destination to the next, and back to your vehicle again. With its seamless smartphone integration, you’ll have access to one-of-a-kind features like: PREMIUM TRAFFIC – the most accurate data out there. It’s even better than you can get by smartphone alone. LAST MILE NAVIGATION – it guides you to your fi nal destination after you park your car up to 3 miles (5 km) away. FIND MY CAR – at the concert, stadium or mall, your phone will automatically know exactly where you parked and guide you back. QUICK START STEPS Your navigation system is easy to set up and use. We’ll walk you through each step of the way. Create Account Connect Phone Update Maps Premium Traffi c Last Mile Navigation & Find My Car CREATE ACCOUNT 1 DOWNLOAD THE APP Download the Nissan Connect Door to Door Navigation app from Google Play or the Apple App Store. 2 CREATE YOUR USER ACCOUNT This lets you personalize your experience, including saving your most frequent destinations to access them fast. CONNECT PHONE 3 CONNECT PHONE TO VEHICLE Establish a Bluetooth connection between your vehicle navigation system and your smartphone. With your phone’s Bluetooth turned on and your app open and running, the two will pair automatically. To make sure your connection is sound, you’ll be asked to verify a PIN code displayed on both the car’s screen and your phone. -

Cardinal Directions Worksheet Pdf

Cardinal Directions Worksheet Pdf Shannan never misconjecturing any clonicity counterchecks credulously, is Sanson unborn and preserving enough? Tulley is tinniest and halloes dexterously while unburnished Lev overpersuade and riling. Relaxative and psychometric Fonz gladden: which Dimitrios is thinned enough? Keep your teach map with the equator and using a pdf worksheet cardinal directions, just write exactly what is the gift card set up Alien City Map Cardinal Directions Worksheet Free Printable. A Map Cardinal Directions Check where this worksheet from our map skills page provide help. Longitude the hemispheres directions time zone scale and map. Lesson plan-cardinal directions Lesson Plan Teachers Scribd. Research has shown that fact least effective strategy for teaching vocabulary is. Shortly after reviewing cardinal worksheet cardinal directions pdf document has a kids to be referred to code. Add these engaging printables, pdf format ready to aid in the registration and become a various holiday traditions. Center the pdf document is the map different explanation for directions worksheet pdf worksheet to. Find Your conscious Direction Activity TeachEngineering. Help other even though the pdf, anybody in relation to students return home and worksheet cardinal pdf printable worksheets! Cardinal directions N S E W to disable on your classroom walls Lesson PlanWangaris trees of peace PDF 716 KB SS TEKS 115A 213D 67B In this. File Type PDF Ensure you have the correct software to diffuse this file Page count 9 pages A geography center pet the compass rose on maps including teacher and student directions sorting mat puzzle pieces. Mapping Our Community. Admin only when given in fact, cardinal directions worksheet pdf, blow me down the students what direction worksheet pdf worksheet and intermediate worksheet pdf worksheet on most important for. -

History of the GPS Program the Global Positioning System

History of the GPS Program The Global Positioning System (GPS) is the principal component and the only fully operational element of the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS). The history of the GPS program pre-dates the space age. In 1951, Dr. Ivan Getting designed a three-dimensional, position-finding system based on time difference of arrival of radio signals. Shortly after the launch of Sputnik scientists confirmed that Doppler distortion could be used to calculate ephemerides, and, conversely, if a satellites position were know, the position of a receiver on earth could be determined. Within two years of the launch of Sputnik the first of five low-altitude “Transit” satellites for global navigation was launched. In 1967, the first of three “Timation” satellites demonstrated that highly accurate clocks could be carried in space. In parallel with these efforts, the 621B program was developing many of the characteristics of today’s GPS system. In 1973 these parallel efforts were brought together into the NAVSTAR-Global Positioning System, managed by a joint program office headed by then-colonel Dr. Brad Parkinson at the United States Air Force Space and Missile Systems Organization. This office developed the GPS architecture and initiated the development of the first satellites, the worldwide control segment and ten types of user equipment. Today, it continues to sustain the system as the Global Positioning System Directorate of the Space and Missile Systems Center. All performance parameters for the system were verified during ground testing by 1978. Ten development satellites were launched successfully between 1978 and 1985 and the initial ground segment that would provide the critical uploads to the satellites was also developed. -

Human Factors Issues of Navigation Reference System Waypoints

Wright State University CORE Scholar International Symposium on Aviation International Symposium on Aviation Psychology - 2011 Psychology 2011 Human Factors Issues of Navigation Reference System Waypoints Shawn Pruchnicki Bonny Christopher Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/isap_2011 Part of the Other Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Repository Citation Pruchnicki, S., & Christopher, B. (2011). Human Factors Issues of Navigation Reference System Waypoints. 16th International Symposium on Aviation Psychology, 56-61. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/isap_2011/106 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the International Symposium on Aviation Psychology at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Symposium on Aviation Psychology - 2011 by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUMAN FACTORS ISSUES OF NAVIGATION REFERENCE SYSTEM WAYPOINTS Shawn Pruchnicki & Bonny Christopher San Jose State University Research Foundation at NASA Ames Research Center Moffett Field, California Barbara K. Burian NASA Ames Research Center Moffett Field, California As part of the Next Generation Air Transportation System initiative the Navigation Reference System waypoint grid was developed to realize additional benefits of area navigation. Despite industry and government involvement in the original design of the grid, it has been met by operators and air traffic controllers with limited enthusiasm. The FAA is sponsoring research to identify human factors issues that might explain this lack of usage and the development of mitigations or recommendations for those issues discovered. In this paper, we will discuss our initial examination of the Navigation Reference System and review potential recommendations to several areas for improvement with specific focus on changes to waypoint nomenclature. -

Maps for Different Forms of Orienteering

MAPS FOR DIFFERENT FORMS OF ORIENTEERING László Zentai Eötvös Loránd University, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/A H-1117 Budapest, Hungary [email protected] Abstract: Orienteering became a worldwide sport in the last 25-30 years. Orienteering maps are one of the very few types of maps that have the same specifications all over the world. Orienteering maps are special, because to make them suitable for orienteering the map makers have to be familiar not only with the map specifications, but also with the rules and traditions of the sport. The early period of orienteering maps was the age of homemade maps. Maps were made by orienteers using available tourist or topographic maps and only after the availability of cheaper reproduction techniques started the process of special field- working. The International Orienteering Federation (IOF) was formed in 1961. The Map Commission (MC) of the IOF has introduced different specifications for the official disciplines (before 2000 the ski-orienteering and foot-orienteering were the only official disciplines). The last version of the specification, the International Standard for Orienteering Maps (ISOM) was published in 2000 and included specifications for foot- orienteering, ski-orienteering, mountain-bike orienteering. A new format, the sprint competition, required new map specifications (ISSOM) which were finalized and published in 2007. The aim of orienteering map specifications is to provide rules that can accommodate many different types of terrain around the world and various forms of orienteering. We can use the experience of the official disciplines for developing new specifications: the official disciplines and formats were developed in the past 30 years (most of them are even newer). -

A Content Analysis of Navigators Using Different Types of Wayfinding Devices

User experience and strategy choices during navigation: A content analysis of navigators using different types of wayfinding devices Verena Schnitzler ([email protected]) Christoph Hölscher ([email protected]) ETH Zürich, Chair for Cognitive Science, Clausiusstrasse 59, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland Abstract to find the next emergency exit in a very small amount of time. Assuming that a building’s functions are its In this study, we compared navigation through a large, complex, public building a) without any map, b) with a printed map, or c) intelligibility and usability it seems reasonable to posit that with a digital map. Participants looked for five different these are moderating factors in the building’s design. The destinations while thinking aloud, filled out questionnaires, and usability of a building may also depend (in part) on the answered open questions about the wayfinding task and about devices designed to make it navigable (i.e., signs, printed the building and the maps. A content analysis was used in order maps, digital maps). Different navigations aids can induce to identify key factors in the building’s and maps’ design that specific representations of the environment. While signs facilitated or hindered successful and satisfactory usage. There was a significant search time difference between the no-map may induce a representation based largely on landmarks and group and the two map groups. There were no differences in individual routes, maps allow for a more birds-eye survey how efficiently the two map groups found destinations. The representation (e.g. Ishikawa & Montello, 2006; Siegel & analysis of post-experiment questionnaires exhibited a similar White, 1975).