Quarterly Report of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Competitiveness “Natural-Born Clusters”

REPORT ON COMPETITIVENESS “NATURAL-BORN CLUSTERS” Pristina, 2014 REPORT ON COMPETITIVENESS “NATURAL-BORN CLUSTERS” Pristina, 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Financing provided by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland in the framework of the Aid for Trade project. REPORT PREPARED BY: Cheng G. Ong – Author Supported by: Ilir Salihu and Paul Wittrock SPECIAL CONTRIBUTIONS PROVIDED BY: Ministry of Trade and Industry: The Cabinet of the Minister Department of Industry Department of Trade Kosovo Investment and Enterprise Support Agency UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (UNDP) KOSOVO QUALITY ASSURANCE: TEUta PURRINI XHABALI, Project Manager, Aid for Trade ANita SmaiLOVIC, Project Associate, Aid for Trade ARtaNE RIZVANOLLI, External Consultant ERËBLINA ELEZAJ, Research Analyst, Policy, Research, Gender and Communication Team BURBUQE DOBRANJA, Communications Associate, Policy, Research, Gender and Communication Team DANIJELA MITIć, Communication Analyst, Policy, Research, Gender and Communication Team A special gratitude goes to all interviewed businesses and other relevant actors. _________________________________________________________________________________ There is no copyright on this document; therefore its content maybe be partially or fully used without the prior permission of UNDP. Its source, however, must be cited. The analysis and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not represent the official position ofU nited Nations Development Programme and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. _________________________________________________________________________________ -

Ce General Conference GC (54)/INF/7 Date: 23 September 2010

Atoms for Peace General Conference GC (54)/INF/7 Date: 23 September 2010 General Distribution Original: English 54th regular session Vienna, 20-24 September 2010 List of Participants Information received by 22 September 2010 Page 1. Member States 1-101 2. Representation of States not Members of the Agency 102 3. Entities Having Received a Standing Invitation to Participate as 103 Observers 4. United Nations and Specialized Agencies 104 5. Intergovernmental Organizations (IGOs) other than United Nations 105-108 and its Specialized Agencies 6. Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) 109-113 7. Individual Observers 114-115 The list of Participants contains information as provided by Delegations. Member States Mr Nikolla CIVICI Director of Applied Nuclear Physics Afghanistan, Islamic Republic of Mr Rustem PACI Head of Delegation: Secretary of Radiation Protection Commission Mr Eklil Ahmad HAKIMI Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Mr Jovan THERESCA Technical Advisor Alternates: Mr Lorenc XHAFERRAJ Mr Abdul M SHOOGUFAN Expert on International Organisations Ambassador Ministry of Foreign Affairs Governor on the Agency's Board of Governors & Resident Representative to the Agency Permanent Mission to the IAEA Algeria, People's Democratic Republic of Mr Abdul Hai NAZIFI Chairman Head of Delegation: High Commission on Atomic Energy Ms Taous FEROUKHI Ambassador* Mr Mohammad Yama AINI Resident Representative to the Agency Second Secretary Permanent Mission to the IAEA Alternate to the Resident Representative Permanent Mission to the IAEA Alternates: -

Honorary Committee

Ambassador Eklil Ahmad Hakimi, Embassy of Afghanistan Ambassador Hans Peter Manz, Embassy of Austria Ambassador Cornelius Smith, Embassy of The Bahamas Ambassador Houda Nonoo, Embassy of Bahrain Ambassador Akramul Qader, Embassy of Bangladesh Chargé d'Affaires Freddy Bersatti, Embassy of Bolivia Ambassador Tebelelo Seretse, Embassy of Botswana Ambassador Mauro Vieira, Embassy of Brazil Ambassador Elena Borislavova Poptodorova, Embassy of Bulgaria Ambassador Angele Niyuhire, Embassy of Burundi Ambassador Gary Doer, Embassy of Canada Ambassador Maria de Fatima Lima da Veiga, Embassy of Cape Verde Ambassador Faida M. Mitifu, Embassy of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Ambassador Muni Figueres, Embassy of Costa Rica Ambassador Pavlos Anastasiades, Embassy of Cyprus Ambassador Petr Gandalovič, Embassy of the Czech Republic Ambassador Peter Taksøe-Jensen, Embassy of Denmark Ambassador Roble Olhaye, Embassy of Djibouti Ambassador Nathalie Cely Suárez, Embassy of Ecuador Ambassador Francisco Altschul, Embassy of El Salvador Ambassador Purificacion Angue Ondo, Embassy of Equatorial Guinea Ambassador Marina Kaljurand, Embassy of Estonia Ambassador Girma Birru Geda, Embassy of Ethiopia Ambassador João Vale de Almeida, Delegation of the European Union to the United States Ambassador Winston Thompson, Embassy of Fiji Ambassador Ritva Koukku-Ronde, Embassy of Finland Ambassador François Delattre, Embassy of France Ambassador Michael Moussa-Adamo, Embassy of Gabon Ambassador Alieu Momodou Ngum, Embassy of The Gambia Ambassador Peter Ammon, Embassy -

Official Documents the World Bank

OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS THE WORLD BANK Street 15, House 19. Tel: (0093) 70113 3328 IBRD IDA I WORLDBANKGROUP Wazir Akbar Khan Afghanistan Country Office Kabul, Afghanistan Public Disclosure Authorized H.E. Eklil Ahmad Hakimi December 29, 2016 Minister of Finance Ministry of Finance Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kabul, Afghanistan Excellency: Re: Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund Grant No. TF014845 Preparation of the "Afghanistan: First Public-Private Partnerships Project" (Formerly "Afghanistan Resource Corridors Project") Public Disclosure Authorized Additional Instructions: Disbursement I refer to the Grant Agreement ("Agreement") between the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (the "Recipient") and the International Development Association (the "World Bank") acting as administrator of grant funds provided by various donors ("Donors") under the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund ("ARTF"), for the above-referenced project, dated May 21, 2013. The Agreement provides that the World Bank may issue additional instructions regarding the withdrawal of the proceeds of preparation Grant No. TF014845-AF ("Grant"). This letter ("Disbursement Letter"), as revised from time to time, constitutes the additional instructions. This is the First Amendment of the Disbursement Letter dated May 21, 2013. This revision is for: * removal of special commitment and reimbursement methods of disbursement; Public Disclosure Authorized * opening of a separate Designated Account under Ministry of Finance for Part C activities of the Project Preparation Grant (PPG); * change in the Designated Account ceiling from fixed to variable; and * change in the reporting of Grant proceeds from Statement of Expenditure (SOE) based to Interim Unaudited Financial Reports (IUFR) based. All other provisions of the Disbursement Letter dated May 21, 2013, except as amended, shall remain in force and effect. -

Foreign Diplomatic Offices in the United States

FOREIGN DIPLOMATIC OFFICES IN THE UNITED STATES AFGHANISTAN phone (212) 750–8064, fax 750–6630 Embassy of Afghanistan His Excellency Narcis Casal De Fonsdeviela 2341 Wyoming Avenue, NW., Washington, DC Ambassador E. and P. 20008 Consular Office: California, La Jolla phone (202) 483–6410, fax 483–6488 ANGOLA His Excellency Eklil Ahmad Hakimi Ambassador E. and P. Embassy of the Republic of Angola Consular Offices: 2100–2108 16th Street, NW., Washington, DC California, Los Angeles 20009 New York, New York phone (202) 785–1156, fax 785–1258 His Excellency Alberto Do Carmo Bento Ribeiro AFRICAN UNION Ambassador E. and P. Delegation of the African Union Mission Consular Offices: 2200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., Floor 4 New York, New York Washington, DC 20037 Texas, Houston Embassy of the African Union ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA phone (202) 293–8006, fax 429–7130 Her Excellency Amina Salum Ali Embassy of Antigua and Barbuda Ambassador (Head of Delegation) 3216 New Mexico Avenue, NW., Washington, DC 20016 ALBANIA phone (202) 362–5122, fax 362–5225 Embassy of the Republic of Albania Her Excellency Deborah Mae Lovell 1312 18th Street, NW., Washington, DC 20036 Ambassador E. and P. / Consul General phone (202) 223–4942, fax 628–7342 Consular Offices: His Excellency Gilbert Galanxhi District of Columbia, Washington Ambassador E. and P. Florida, Miami Consular Offices: New York, New York Connecticut, Greenwich Puerto Rico, Guaynabo Georgia, Avondale Estates ARGENTINA Louisiana, New Orleans Massachusetts, Boston Embassy of the Argentine Republic Michigan, West Bloomfield 1600 New Hampshire Avenue, NW., Washington, DC 20009 Missouri, Blue Springs phone (202) 238–6400, fax 332–3171 New York, New York Her Excellency Maria Cecilia Nahon North Carolina, Southern Pines Ambassador E. -

Information As of 20 March 2017 Has Been Used in Preparation of This Directory

Information as of 20 March 2017 has been used in preparation of this directory. PREFACE The Central Intelligence Agency publishes and updates the online directory of Chiefs of State and Cabinet Members of Foreign Governments weekly. The directory is intended to be used primarily as a reference aid and includes as many governments of the world as is considered practical, some of them not officially recognized by the United States. Regimes with which the United States has no diplomatic exchanges are indicated by the initials NDE. Governments are listed in alphabetical order according to the most commonly used version of each country's name. The spelling of the personal names in this directory follows transliteration systems generally agreed upon by US Government agencies, except in the cases in which officials have stated a preference for alternate spellings of their names. NOTE: Although the head of the central bank is listed for each country, in most cases he or she is not a Cabinet member. Ambassadors to the United States and Permanent Representatives to the UN, New York, have also been included. Key To Abbreviations Adm. Admiral Admin. Administrative, Administration Asst. Assistant Brig. Brigadier Capt. Captain Cdr. Commander Cdte. Comandante Chmn. Chairman, Chairwoman Col. Colonel Ctte. Committee Del. Delegate Dep. Deputy Dept. Department Dir. Director Div. Division Dr. Doctor Eng. Engineer Fd. Mar. Field Marshal Fed. Federal Gen. General Govt. Government Intl. International Lt. Lieutenant Maj. Major Mar. Marshal Mbr. Member Min. Minister, Ministry NDE No Diplomatic Exchange Org. Organization Pres. President Prof. Professor RAdm. Rear Admiral Ret. Retired Sec. Secretary VAdm. -

Board of Governors (As of 31 December 2017)

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 www.adb.org/ar2017 Keywords: board of governors, governors, board Board of Governors (as of 31 December 2017) Member Governor Alternate Governor Afghanistan Eklil Ahmad Hakimi Mohammad Khalid Payenda1 Armenia Vache Gabrielyan Armen Hayrapetyan Australia Scott Morrison MP Kelly O'Dwyer MP Austria Johann Georg Schelling Elisabeth Gruber2 Azerbaijan Samir Sharifov Shahin Mustafayev Bangladesh Abul Maal A. Muhith Kazi Shofiqul Azam Belgium Johan Van Overtveldt Alexander De Croo3 Bhutan Lyonpo Namgay Dorji Nim Dorji Brunei Darussalam Pehin Dato Abdul Rahman Ibrahim Ahmaddin Abdul Rahman4 Cambodia Aun Pornmoniroth Vongsey Vissoth Canada Chrystia Freeland5 (vacant) China, People’s Republic of Xiao Jie Shi Yaobin Cook Islands Mark Brown Garth Henderson Denmark Morten Jespersen Jan Top Christensen6 Fiji Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum Ariff Ali7 Finland Elina Kalkku Satu Santala France Bruno Le Maire8 Odile Renaud-Basso Georgia Mamuka Bakhtadze9 Dimitry Kumsishvili10 Germany Hans-Joachim Fuchtel Marianne Kothe Hong Kong, China Paul Chan Mo-po11 Norman Chan India Arun Jaitley Subhash Chandra Garg12 Indonesia Sri Mulyani Indrawati Bambang P.S. Brodjonegoro Ireland Paschal Donohoe13 Paul Ryan Italy Ignazio Visco Gelsomina Vigliotti14 Japan Taro Aso Haruhiko Kuroda Kazakhstan Timur Suleimenov15 Ruslan Bekatayev16 1 Succeeded Mohammad Mustafa Mastoor in August. 2 Succeeded Gunther Schönleitner in March. 3 Succeeded Ronald de Swert in January. 4 Succeeded Nazmi Mohamad in April. 5 Succeeded Stephane Dion in January. 6 Succeeded Christian Dons Christensen in March. 7 Succeeded Barry Whiteside in May. 8 Succeeded Michel Sapin in July. 9 Succeeded Dimitry Kumsishvili in November. 10 Succeeded Giorgi Gakharia in November. 11 Succeeded John Tsang Chun-wah in January. -

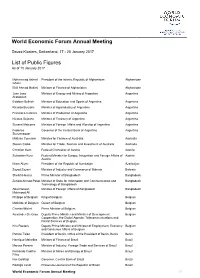

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos-Klosters, Switzerland, 17 - 20 January 2017 List of Public Figures As of 10 January 2017 Mohammad Ashraf President of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Afghanistan Ghani Eklil Ahmad Hakimi Minister of Finance of Afghanistan Afghanistan Juan Jose Minister of Energy and Mining of Argentina Argentina Aranguren Esteban Bullrich Minister of Education and Sports of Argentina Argentina Ricardo Buryaile Minister of Agroindustry of Argentina Argentina Francisco Cabrera Minister of Production of Argentina Argentina Nicolas Dujovne Minister of Treasury of Argentina Argentina Susana Malcorra Minister of Foreign Affairs and Worship of Argentina Argentina Federico Governor of the Central Bank of Argentina Argentina Sturzenegger Mathias Cormann Minister for Finance of Australia Australia Steven Ciobo Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment of Australia Australia Christian Kern Federal Chancellor of Austria Austria Sebastian Kurz Federal Minister for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs of Austria Austria Ilham Aliyev President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Zayed Zayani Minister of Industry and Commerce of Bahrain Bahrain Sheikh Hasina Prime Minister of Bangladesh Bangladesh Zunaid Ahmed Palak Minister of State for Information and Communication and Bangladesh Technology of Bangladesh Abul Hassan Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bangladesh Bangladesh Mahmood Ali Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Belgium Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Charles Michel Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium -

Urgent Action

UA: 120/12 Index: ASA 11/008/2012 Afghanistan Date: 30 April 2012 URGENT ACTION JOURNALIST DETAINED, RISKS TORTURE OR DEATH Afghan TV journalist Nasto Naderi has been detained without charge since 21 April, when he was summoned to the General prosecutor’s office for questioning over a controversial broadcast. He is at grave risk of torture or death. Nasto Naderi works for Noorin TV in the capital, Kabul, and hosts a program called "Salaam to my homeland”, known for revealing cases of corruption, criminality and other controversial issues, often implicating high-profile Afghan government figures and members of the Afghan parliament. The manager of Noorin TV told Amnesty International that the Attorney General had summoned Nasto Naderi to his office on 21 April for questioning after the broadcast of a program critical of the mayor of Kabul. He was arrested without charge at the office, and has been held since then in Kabul Detention Centre, without access to a lawyer or to a court. Nasto Naderi may have been arrested and detained solely for exposing corruption in the awarding of road-construction contracts by Kabul Municipality in "Salaam to my homeland". Under Afghanistan's Media Law, if he was alleged to have committed a media-related offence, he should have, been investigated first by the Media Violation Inquiry Commission rather than the Attorney General’s office. As a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Afghanistan is legally obliged to protect and respect the right to freedom of expression. The arbitrary arrest of Nasto Naderi for peacefully expressing his views clearly violates these obligations. -

The World Factbook

The World Factbook South Asia :: Afghanistan Introduction :: Afghanistan Background: Ahmad Shah DURRANI unified the Pashtun tribes and founded Afghanistan in 1747. The country served as a buffer between the British and Russian Empires until it won independence from notional British control in 1919. A brief experiment in democracy ended in a 1973 coup and a 1978 communist counter-coup. The Soviet Union invaded in 1979 to support the tottering Afghan communist regime, touching off a long and destructive war. The USSR withdrew in 1989 under relentless pressure by internationally supported anti-communist mujahedin rebels. A series of subsequent civil wars saw Kabul finally fall in 1996 to the Taliban, a hardline Pakistani-sponsored movement that emerged in 1994 to end the country's civil war and anarchy. Following the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks, a US, Allied, and anti-Taliban Northern Alliance military action toppled the Taliban for sheltering Osama BIN LADIN. The UN-sponsored Bonn Conference in 2001 established a process for political reconstruction that included the adoption of a new constitution, a presidential election in 2004, and National Assembly elections in 2005. In December 2004, Hamid KARZAI became the first democratically elected president of Afghanistan and the National Assembly was inaugurated the following December. KARZAI was re-elected in August 2009 for a second term. Despite gains toward building a stable central government, a resurgent Taliban and continuing provincial instability - particularly in the south and -

OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS the WORLD BANK IBRD IDA I Woraaunkoro

OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS THE WORLD BANK IBRD IDA I WORaAuNKORO SHUBHAM CHAUDHURI Country Director, Afghanistan South Asia Region June 11, 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized H.E. Eklil Ahmad Hakimi Minister of Finance Ministry of Finance Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kabul, Afghanistan Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund Grant No. TF015005 System Enhancement for Health Action in Transition Project Amendment to Amended and Restated Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund Grant Agreement Excellency: Public Disclosure Authorized We refer to the Amended and Restated Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund Grant Agreement dated June 13, 2015 between the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (the "Recipient") and the International Development Association (the "World Bank"), acting as administrator of the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (the "ARTF") (the "Grant Agreement"), for the above referenced project. We propose amending the Grant Agreement to increase the available Grant Funds by sixty million United States dollars (US$60,000,000). This increase reflects additional contributions received from ARTF's donors. Accordingly, the Grant Agreement is hereby amended as follows: Public Disclosure Authorized 1. A new paragraph (E) is added in the WHEREAS section on the first page as follows: "(E) the Recipient requested, and the ARTF Management Committee and the World Bank approved, a release of a third tranche of the Original Financing Allocation in an amount equal to sixty million United States Dollars ($60,000,000), which the Recipient has requested the World Bank to make available as part of the Second Grant (as hereinafter defined) to assist in the financing of the Project;" 2. Section 3.01 is amended to read as follows: "3.01. -

![January [776 Kb*]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0172/january-776-kb-4410172.webp)

January [776 Kb*]

ELLLLIGIGEEN TTE NCC INN E I A L A L G AA G E R R E N T T N C N N C Y E Y E C C U U A N N A C I IT C I T E RI R E D S E E D S TAT F A MAM TATEESSO OF Directorate of Intelligence Chiefs ofState& CabinetMembers OF FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS A DIRECTORY DI CS 2012-01 Supercedes DI CS 2011-12 January 2012 Chiefs ofState& CabinetMembers OF FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS A DIRECTORY Information received as of 20 January 2012 has been used in preparation of this directory. DI CS 2012-01 Supercedes DI CS 2011-12 January 2012 PREFACE The Chiefs of State and Cabinet Members of Foreign Governments directory is intended to be used primarily as a reference aid and includes as many governments of the world as is considered practical, some of them not officially recognized by the United States. Regimes with which the United States has no diplomatic exchanges are indicated by the initials NDE. Governments are listed in alphabetical order according to the most commonly used version of each country’s name. The spelling of the personal names in this directory follows transliteration systems generally agreed upon by US Government agencies, except in the cases in which officials have stated a preference for alternate spellings of their names. NOTE: Although the head of the central bank is listed for each country, in most cases he or she is not a Cabinet member. Ambassadors to the United States and Permanent Representatives to the UN, New York, have also been included.