Zachman, Maryland Lucky R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Directory MINNESOTA

142 Congressional Directory MINNESOTA THIRD DISTRICT JIM RAMSTAD, Republican, of Minnetonka, MN; born in Jamestown, ND, May 6, 1946; education: University of Minnesota, B.A., Phi Beta Kappa, 1968; George Washington Univer- sity, J.D. with honors, 1973; military service: first lieutenant, U.S. Army Reserves, 1968–74; elected to the Minnesota Senate, 1980; reelected 1982, 1986; assistant minority leader; attorney; adjunct professor; member: Ways and Means Committee; elected to the 102nd Congress, No- vember 6, 1990; reelected to each succeeding Congress. Office Listings 103 Cannon House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515–2303 .......................... (202) 225–2871 Administrative Assistant.—Dean Peterson. Legislative Director.—Karin Hope. Executive Assistant / Scheduler.—Valerie Nelson. 1809 Plymouth Road South, Suite 300, Minnetonka, MN 55305 .............................. (952) 738–8200 District Director.—Shari Nichols. Counties: Dakota (part), Hennepin (part), Scott (part). CITIES AND TOWNSHIPS: Bloomington, Brooklyn Center, Brooklyn Park, Burnsville, Champlin, Corcoran, Dayton, Deephaven, Eden Prarie, Edina, Excelsior, Greenwood, Hanover, Hassan, Hopkins, Independence, Long Lake, Loretto, Maple Grove, Maple Plain, Medicine Lake, Medina, Minnetonka Beach, Minnetonka, Minnetrista, Mound, Orono, Osseo, Plymouth, Rockford, Rogers, Saint Bonifacius, Savage, Shorewood, Spring Park, Tonka Bay, Wayzata, and Woodland. Population (1990), 546,888. ZIP Codes: 55044 (part), 55305–06, 55311, 55316, 55323, 55327–28, 55331, 55337, 55340–41, 55343, 55344–47, 55356– 57, 55359, 55361, 55364, 55369, 55373–75, 55378, 55384, 55387, 55391, 55420, 55423, 55424 (part), 55425, 55428– 31, 55435 (part), 55436 (part), 55437–38, 55439 (part), 55441–47 *** FOURTH DISTRICT BETTY MCCOLLUM, Democrat, of North St. Paul, MN; born on July 12, 1954, in Min- neapolis, MN; education: A.A., Inver Hills Community College; B.S., College of St. -

Union Calendar No. 512 107Th Congress, 2D Session –––––––––– House Report 107–811

1 Union Calendar No. 512 107th Congress, 2d Session –––––––––– House Report 107–811 ACTIVITIES AND SUMMARY REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE BUDGET HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES One Hundred Seventh Congress (Pursuant to House Rule XI, Cl. 1.(d)) JANUARY 2, 2003.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 19–006 WASHINGTON : 2003 VerDate Jan 31 2003 01:23 May 01, 2003 Jkt 019006 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR811.XXX HR811 E:\seals\congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON THE BUDGET JIM NUSSLE, Iowa, Chairman JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire JOHN M. SPRATT, JR., South Carolina, Vice Chairman Ranking Minority Member PETER HOEKSTRA, Michigan JIM MCDERMOTT, Washington Vice Chairman BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi CHARLES F. BASS, New Hampshire KEN BENTSEN, Texas GIL GUTKNECHT, Minnesota JIM DAVIS, Florida VAN HILLEARY, Tennessee EVA M. CLAYTON, North Carolina MAC THORNBERRY, Texas DAVID E. PRICE, North Carolina JIM RYUN, Kansas GERALD D. KLECZKA, Wisconsin MAC COLLINS, Georgia BOB CLEMENT, Tennessee GARY G. MILLER, California JAMES P. MORAN, Virginia PAT TOOMEY, Pennsylvania DARLENE HOOLEY, Oregon WES WATKINS, Oklahoma TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin DOC HASTINGS, Washington CAROLYN MCCARTHY, New York JOHN T. DOOLITTLE, California DENNIS MOORE, Kansas ROB PORTMAN, Ohio MICHAEL M. HONDA, California RAY LAHOOD, Illinois JOSEPH M. HOEFFEL III, Pennsylvania KAY GRANGER, Texas RUSH D. HOLT, New Jersey EDWARD SCHROCK, Virginia JIM MATHESON, Utah JOHN CULBERSON, Texas [Vacant] HENRY E. BROWN, JR., South Carolina ANDER CRENSHAW, Florida ADAM PUTNAM, Florida MARK KIRK, Illinois [Vacant] PROFESSIONAL STAFF RICH MEADE, Chief of Staff THOMAS S. -

Congressional Directory MINNESOTA

140 Congressional Directory MINNESOTA MINNESOTA (Population 2000, 4,919,479) SENATORS PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Democrat, of Northfield, MN; born in Washington, DC, July 21, 1944; attended Wakefield and Yorktown High Schools, Arlington, VA; B.A., political science, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1965; Ph.D., political science, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1969; professor of political science, Carleton College, Northfield, MN, 1969–90; director, Minnesota Community Energy Program; member, Democratic Farmer Labor Party, and numerous peace and justice organizations; publisher of three books: ‘‘How the Rural Poor Got Power’’, ‘‘Powerline’’ and ‘‘The Conscience of a Liberal Reclaiming the Compas- sionate Agenda’’; published several articles; married to the former Sheila Ison; three children: David, Marcia, and Mark; committees: Agriculture; Foreign Relations; Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions; Indian Affairs; Small Business and Entrepreneurship; Veterans’ Affairs; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 6, 1990; reelected to each succeeding Senate term. Office Listings http://www.senate.gov/∼wellstone [email protected] 136 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510–2303 ............................... (202) 224–5641 Administrative Assistant.—Colin McGinnis. FAX: 224–8438 Office Manager.—Jeffrey Levensaler. Legislative Director.—Brian Ahlberg. Court International Building, 2550 University Avenue West, St. Paul, MN 55114– 1025 .......................................................................................................................... -

State of Minnesota Special Redistricting Panel C0-01

STATE OF MINNESOTA SPECIAL REDISTRICTING PANEL C0-01-160 Susan M. Zachman, Maryland Lucky R. Rosenbloom, Victor L.M. Gomez, Gregory G. Edeen, Jeffrey E. Karlson, Diana V. Bratlie, Brian J. LeClair and Gregory J. Ravenhorst, individually and on behalf of all citizens and voting residents of Minnesota similarly situated, FINAL ORDER Plaintiffs, Adopting a Congressional and Redistricting Plan Patricia Cotlow, Thomas L. Weisbecker, Theresa Silka, Geri Boice, William English, Benjamin Gross, Thomas R. Dietz and John Raplinger, individually and on behalf of all citizens and voting residents of Minnesota similarly situated, Plaintiffs-Intervenors, and Jesse Ventura, Plaintiff-Intervenor, and Roger D. Moe, Thomas W. Pugh, Betty McCollum, Martin Olav Sabo, Bill Luther, Collin C. Peterson and James L. Oberstar, Plaintiffs-Intervenors, vs. Mary Kiffmeyer, Secretary of State of Minnesota, and Doug Gruber, Wright County Auditor, individually and on behalf of all Minnesota county chief election officers, Defendants. -1- O R D E R On January 4, 2001, Susan M. Zachman et. al brought an action in Wright County District Court alleging that “the present congressional district boundaries in the State of Minnesota violate Plaintiffs’ rights to due process and equal protection guaranteed by the United States Constitution.” (Zachman Compl. at 12.) The Zachman plaintiffs then petitioned Chief Justice Kathleen Blatz of the Minnesota Supreme Court to appoint a Special Redistricting Panel to oversee all of Minnesota’s 2001-2002 redistricting litigation. (Zachman Pet. for Appointment of Spec. Redistricting Panel at 1.) Pursuant to her authority under Minnesota law, Chief Justice Blatz appointed this panel on July 12, 2001, directing us to adopt congressional and legislative redistricting plans only in the event the legislature failed to do so in a timely manner. -

Appendix G: Mailing List

Appendix G: Mailing List Appendix G: Mailing List 145 Appendix G: Mailing List The following is an initial list of government offices, private organizations, and individuals who will receive notice of the availability of this CCP. We continue to add to this list. Elected Officials Senator Norm Coleman Senator Mark Dayton Representative Bill Luther Representative Collin Peterson Representative Mike Kennedy Governor Tim Pawlenty Representative Betty McCollum Representative Martin Sabo Tribal Government Red Lake Band of the Chippewa Indians Local Government City of Baudette City of Bemidji City of Hallock City of Roseau City of Red Lake Falls City of Thief River Falls City of Warren City of Middle City City of Grygla City of Crookston City of Newfolden Beltrami County Kittson County Lake of the Woods County Pennington County Red Lake County Roseau County Marshall County Beltrami Co. Soil & Water Conservation District Kittson Co. Soil & Water Conservation District Lake of the Woods Co. Soil & Water Conservation Dist. Pennington Co. Soil & Water Conservation Dist. Red Lake Co. Soil & Water Conservation District Roseau Co. Soil & Water Conservation Dist. Marshall Co. Soil & Water Conservation District Red River Watershed Management Board Red River Basin Flood Damage Reduction Work Group Red Lake Watershed District Mediation Committee Snake River/Middle River Watershed Mediation Committee Two Rivers Watershed District Roseau River Watershed District Appendix G: Mailing List 147 Federal Agencies USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service USFWS, -

SENATE-Tuesday, February 11, 1997

February 11, 1997 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 1851 SENATE-Tuesday, February 11, 1997 The Senate met at 2:15 p.m., and was out that nomination this afternoon, honest exchange of views. Let me one called to order by the President pro and we will attempt to reach an agree more time just make clear to col tempore [Mr. THURMOND]. ment limiting debate to approximately leagues what this amendment says. 20 minutes equally divided but we will, This amendment says that if we are PRAYER of course, wait until the committee has going to make a commitment by way The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John officially reported it and then bring it of a constitutional amendment to bal Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: up as shortly thereafter as possible. ance the budget, then we go on record Eternal Father, You have told us Following that vote, we will continue that the Federal outlays, as we do this, that the things we can see are tem debate on the balanced budget amend should not be reduced in a manner that porary, but the things which are un ment, and it is my understanding that disproportionately affects outlays for seen are eternal. We confess that what Senator REID will be prepared to offer education, nutrition, and health pro is seen captivates our attention. It is his amendment relative to Social Secu grams for poor children. easy to get lost in the labyrinth of rity. The amendment will be debated Yesterday my colleague, Senator life's enigmas. The media constantly today and tomorrow, and we hope to HATCH, said I was asking for an exemp remind us of violence and vandalism, set a vote on or in relation to the Reid tion. -

Statistics of the Presidential and Congressional Election of Nov.7

STATISTICS OF THE PRESIDENTIAL AND CONGRESSIONAL ELECTION OF NOVEMBER 7, 2000 SHOWING THE HIGHEST VOTE FOR PRESIDENTIAL ELECTORS, AND THE VOTE CAST FOR EACH NOMINEE FOR UNITED STATES SENATOR, REPRESENTATIVE, RESIDENT COMMIS- SIONER, AND DELEGATE TO THE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS, TOGETHER WITH A RECAPITULATION THEREOF, INCLUDING THE ELECTORAL VOTE COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL SOURCES BY JEFF TRANDAHL CLERK OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES (Corrected to June 21, 2001) WASHINGTON : 2001 VerDate 23-MAR-99 13:50 Jul 10, 2001 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 0217 Sfmt 0217 C:\DBASE\STATS107.TXT PUB1 PsN: PUB1 STATISTICS OF THE PRESIDENTIAL AND CONGRESSIONAL ELECTION OF NOVEMBER 7, 2000 (Number which precedes name of candidate designates congressional district. Since party names for Presidential Electors for the same candidate vary from state to state, the most commonly used name is listed in parentheses.) ALABAMA FOR PRESIDENTIAL ELECTORS Republican .................................................................................................. 941,173 Democratic .................................................................................................. 692,611 Independent ................................................................................................ 1 25,896 Libertarian ................................................................................................. 5,893 Write-in ....................................................................................................... 699 FOR UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE -

Federal Government President of the United States

Chapter Eight Federal Government President of the United States .......................................................................474 Vice President of the United States ................................................................474 President’s Cabinet .........................................................................................474 Minnesota’s U.S. Senators .............................................................................475 Minnesota Congressional District Map ..........................................................476 Minnesota’s U.S. Representatives ..................................................................477 Minnesotans in Congress Since Statehood .....................................................480 Supreme Court of the United States ...............................................................485 Minnesotans on U.S. Supreme Court Since Statehood ..................................485 U.S. Court of Appeals .....................................................................................486 U.S. District Court .........................................................................................486 Office of the U.S. Attorney ............................................................................487 Presidents and Vice Presidents of the United States ......................................488 B Capitol Beginnings B The exterior of the Minnesota Capitol with the dome still unfinished, viewed from the southwest, on June 1, 1901. This photo was taken from where the front steps -

Gems Sovc Report

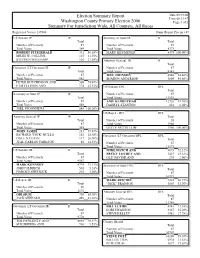

Election Summary Report Date:09/19/06 Time:08:21:47 Washington County Primary Election 2006 Page:1 of 2 Summary For Jurisdiction Wide, All Counters, All Races Registered Voters 139884 Num. Report Precinct 87 US Senator IP IP Secretary of State IR R Total Total Number of Precincts 87 Number of Precincts 87 Total Votes 584 Total Votes 8375 ROBERT FITZGERALD 331 56.68% MARY KIFFMEYER 8375 100.00% MILES W. COLLINS 127 21.75% STEPHEN WILLIAMS 126 21.58% Attorney General IR R Total Governor LT Governor IP IP Number of Precincts 87 Total Total Votes 8345 Number of Precincts 87 JEFF JOHNSON 4540 54.40% Total Votes 682 SHARON ANDERSON 3805 45.60% PETER HUTCHINSON AND 508 74.49% PAM ELLISON AND 174 25.51% US Senator DFL DFL Total Secretary of State IP IP Number of Precincts 87 Total Total Votes 13538 Number of Precincts 87 AMY KLOBUCHAR 12720 93.96% Total Votes 548 DARRYL STANTON 818 6.04% JOEL SPOONHEIM 548 100.00% US Rep 4 - DFL DFL Attorney General IP IP Total Total Number of Precincts 20 Number of Precincts 87 Total Votes 1960 Total Votes 585 BETTY MCCOLLUM 1960 100.00% JOHN JAMES 231 39.49% RICHARD "DICK" BULLO 152 25.98% Governor LT Governor DFL DFL DALE NATHAN 117 20.00% Total JUAL CARLOS CARLSON 85 14.53% Number of Precincts 87 Total Votes 13375 US Senator IR R MIKE HATCH AND 9673 72.32% Total BECKY LOUREY AND 3427 25.62% Number of Precincts 87 OLE' SAVIOR AND 275 2.06% Total Votes 9567 MARK KENNEDY 8774 91.71% Secretary of State DFL DFL JOHN ULDRICH 501 5.24% Total HAROLD SHUDLICK 292 3.05% Number of Precincts 87 Total Votes 10791 US Rep -

STANDING COMMITTEES of the HOUSE* Agriculture

STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE* [Republicans in roman; Democrats in italic; Independents in bold.] [Room numbers beginning with H are in the Capitol, with CHOB in the Cannon House Office Building, with LHOB in the Longworth House Office Building, with RHOB in the Rayburn House Office Building, with H1 in O'Neill House Office Building, and with H2 in the Ford House Office Building] Agriculture 1301 Longworth House Office Building, phone 225±2171, fax 225±0917 http://www.house.gov/agriculture meets first Tuesday of each month Larry Combest, of Texas, Chairman. Bill Barrett, of Nebraska, Vice Chairman. John A. Boehner, of Ohio. Charles W. Stenholm, of Texas. Thomas W. Ewing, of Illinois. øGeorge E. Brown, Jr.¿, of California. Bob Goodlatte, of Virginia. Gary A. Condit, of California. Richard W. Pombo, of California. Collin C. Peterson, of Minnesota. Charles T. Canady, of Florida. Calvin M. Dooley, of California. Nick Smith, of Michigan. Eva M. Clayton, of North Carolina. Terry Everett, of Alabama. David Minge, of Minnesota. Frank D. Lucas, of Oklahoma. Earl F. Hilliard, of Alabama. Helen Chenoweth, of Idaho. Earl Pomeroy, of North Dakota. John N. Hostettler, of Indiana. Tim Holden, of Pennsylvania. Saxby Chambliss, of Georgia. Sanford D. Bishop, Jr., of Georgia. Ray LaHood, of Illinois. Bennie G. Thompson, of Mississippi. Jerry Moran, of Kansas. John Elias Baldacci, of Maine. Bob Schaffer, of Colorado. Marion Berry, of Arkansas. John R. Thune, of South Dakota. Virgil H. Goode, Jr., of Virginia. William L. Jenkins, of Tennessee. Mike McIntyre, of North Carolina. John Cooksey, of Louisiana. Debbie Stabenow, of Michigan. -

The United States House of Representatives

THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES “Tough but doable” was the way Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee Executive Director Howard Wolfson described the Democrats' chances of taking back the House of Representative last Friday. Wolfson had a rough week. Charlie Cook, the respected non-partisan political analyst who is listened to by political reporters, and maybe more importantly, by political PACs, wrote that the math just didn’t seem to be there for the Democrats to pick up the net of six seats they’d need to regain control of the House. During the spring and summer, Cook believed that the Democrats could overcome "the math” with their strength on domestic issues. But, despite a slight edge (48% Democrat- 46% Republican) in the “generic ballot question" (“If the election were held today for Congress, for whom would you vote?”) Democrats haven’t put the issues together in a way to produce the tide it would take to move enough races to produce a Democratic House. Last summer, not only Cook, but top Democrats believed that the Enron, WorldCom and Arthur Anderson scandals, along with the plummeting stock market, had created a climate that could sweep the Democrats back. At one point they even fantasized that all 40 or so competitive races could break their way. But, by August, guns had replaced butter as the overarching national political theme, and the Democrats lost that “mo.” A driving force behind the vote on the Iraq resolution was burning desire by the Democratic leadership to get the focus back on the economy. Indeed, the day after the vote, House Democratic Leader Dick Gephardt and Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle held a high profile economic forum as a signal that the economy was the main concern of Democrats. -

Federal Government President of the United States

Chapter Eight Federal Government President of the United States .......................................................................466 Vice President of the United States ................................................................466 President’s Cabinet .........................................................................................466 Minnesota’s U.S. Senators .............................................................................467 Minnesota Congressional District Map ..........................................................468 Minnesota’s U.S. Representatives ..................................................................469 Minnesotans in Congress Since Statehood .....................................................472 Supreme Court of the United States ...............................................................477 Minnesotans on U.S. Supreme Court Since Statehood ..................................477 U.S. Court of Appeals .....................................................................................478 U.S. District Court .........................................................................................478 Office of the U.S. Attorney ............................................................................479 Presidents and Vice Presidents of the United States ......................................480 Federal Government PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES Donald J. Trump (Republican) 45th President of the United States Elected: 2016 Term: Four years Term expires: January 2021 Salary: $400,000