Judging the J Pouch: a Pictorial Review Shannon P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Practice Parameters for the Treatment of Patients with Dominantly Inherited Colorectal Cancer

Practice Parameters For The Treatment Of Patients With Dominantly Inherited Colorectal Cancer Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 2003;46(8):1001-1012 Prepared by: The Standards Task Force The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons James Church, MD; Clifford Simmang, MD; On Behalf of the Collaborative Group of the Americas on Inherited Colorectal Cancer and the Standards Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is dedicated to assuring high quality patient care by advancing the science, prevention, and management of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum, and anus. The standards committee is composed of Society members who are chosen because they have demonstrated expertise in the specialty of colon and rectal surgery. This Committee was created in order to lead international efforts in defining quality care for conditions related to the colon, rectum, and anus. This is accompanied by developing Clinical Practice Guidelines based on the best available evidence. These guidelines are inclusive, and not prescriptive. Their purpose is to provide information on which decisions can be made, rather than dictate a specific form of treatment. These guidelines are intended for the use of all practitioners, health care workers, and patients who desire information about the management of the conditions addressed by the topics covered in these guidelines. Practice Parameters for the Treatment of Patients With Dominantly Inherited Colorectal Cancer Inherited colorectal cancer includes two main syndromes in which predisposition to the disease is based on a germline mutation that may be transmitted from parent to child. -

Second European Evidence-Based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis: Special Situations

CROHNS-00649; No of Pages 33 Journal of Crohn's and Colitis (2012) xx, xxx–xxx Available online at www.sciencedirect.com SPECIAL ARTICLE Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis: Special situations Gert Van Assche⁎,1,2, Axel Dignass⁎⁎,2, Bernd Bokemeyer1, Silvio Danese1, Paolo Gionchetti1, Gabriele Moser1, Laurent Beaugerie1, Fernando Gomollón1, Winfried Häuser1, Klaus Herrlinger1, Bas Oldenburg1, Julian Panes1, Francisco Portela1, Gerhard Rogler1, Jürgen Stein1, Herbert Tilg1, Simon Travis1, James O. Lindsay1 Received 30 August 2012; accepted 3 September 2012 KEYWORDS Ulcerative colitis; Anaemia; Pouchitis; Colorectal cancer surveillance; Psychosomatic; Extraintestinal manifestations Contents 8. Pouchitis ............................................................ 0 8.1. General ......................................................... 0 8.1.1. Symptoms ................................................... 0 ⁎ Correspondence to: G. Van Assche, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Mt. Sinai Hospital and University Health Network, University of Toronto and University of Leuven, 600 University Avenue, Toronto, ON, Canada M5G 1X5. ⁎⁎ Correspondence to: A. Dignass, Department of Medicine 1, Agaplesion Markus Hospital, Wilhelm-Epstein-Str. 4, D-60431 Frankfurt/Main, Germany. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (G. Van Assche), [email protected] (A. Dignass). 1 On behalf of ECCO. 2 G.V.A. and A.D. acted as convenors of the consensus and contributed equally to this paper. 1873-9946/$ - see front matter © 2012 European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.005 Please cite this article as: Van Assche G, et al, Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis: Special situations, Journal of Crohn's and Colitis (2012), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.005 2 G. -

Management of Low Rectal Cancer Complicating Ulcerative Colitis: Proposal of a Treatment Algorithm

cancers Viewpoint Management of Low Rectal Cancer Complicating Ulcerative Colitis: Proposal of a Treatment Algorithm Bruno Sensi 1,*, Giulia Bagaglini 1, Vittoria Bellato 1 , Daniele Cerbo 1 , Andrea Martina Guida 1 , Jim Khan 2 , Yves Panis 3, Luca Savino 4, Leandro Siragusa 1 and Giuseppe S. Sica 1 1 Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Policlinico Tor Vergata, 00133 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (V.B.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (A.M.G.); [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (G.S.S.) 2 Colorectal Surgery Department, Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth NHS Trust, Portsmouth PO6 3LY, UK; [email protected] 3 Service de Chirurgie Colorectale, Pôle des Maladies de L’appareil Digestif (PMAD), Université Denis-Diderot (Paris VII),Hôpital Beaujon, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), 100, Boulevard du Général-Leclerc, 92110 Clichy, France; [email protected] 4 Pathology, Department of Biomedicine and Prevention, Policlinico Tor Vergata, 00133 Rome, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-338-535-2902 Simple Summary: This article expresses the viewpoint of the authors’ management of low rectal cancer in ulcerative colitis (UC). This subject suffers from a paucity of literature and therefore management decision is very difficult to take. The aim of this paper is to provide a structured Citation: Sensi, B.; Bagaglini, G.; approach to a challenging situation. It is subdivided into two parts: a first part where the existing Bellato, V.; Cerbo, D.; Guida, A.M.; literature is reviewed critically, and a second part in which, on the basis of the literature review Khan, J.; Panis, Y.; Savino, L.; and their extensive clinical experience, a management algorithm is proposed by the authors to offer Siragusa, L.; Sica, G.S. -

The Natural History of Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Syndrome: a 24 Year Review of a Single Center Experience in Screening, Diagnosis, and Outcomes

Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49 (2014) 82–86 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Pediatric Surgery journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jpedsurg The natural history of familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome: A 24 year review of a single center experience in screening, diagnosis, and outcomes Raelene D. Kennedy a,⁎, D. Dean Potter a, Christopher R. Moir a, Mounif El-Youssef b a Division of Pediatric Surgery, Department of Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55905 b Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Pediatrics, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55905 article info abstract Article history: Purpose: Understanding the natural history of Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) will guide screening and Received 17 September 2013 aid clinical management. Accepted 30 September 2013 Methods: Patients with FAP, age ≤20 years presenting between 1987 and 2011, were reviewed for presentation, diagnosis, extraintestinal manifestations, polyp burden, family history, histology, gene Key words: mutation, surgical intervention, and outcome. Familial adenomatous polyposis Results: One hundred sixty-three FAP patients were identified. Diagnosis was made by colonoscopy (69%) or Pediatric genetic screening (25%) at mean age of 12.5 years. Most children (58%) were asymptomatic and diagnosed via Screening screening due to family history. Rectal bleeding was the most common (37%) symptom prompting evaluation. Colon polyps appeared by mean age of 13.4 years with N50 polyps at the time of diagnosis in 60%. Cancer was found in 1 colonoscopy biopsy and 5 colectomy specimens. Family history of FAP was known in 85%. 53% had genetic testing, which confirmed APC mutation in 88%. Extraintestinal manifestations included congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (11.3%), desmoids (10.6%), osteomas (6.7%), epidermal cysts (5.5%), extranumerary teeth (3.7%), papillary thyroid cancer (3.1%), and hepatoblastoma (2.5%). -

When a Case of Ulcerative Colitis Requires Mucosectomy and Hand-Sewn Ileo-Anal Pouch Anastomosis Mary Teresa M O’Donnell1,2*, Joshua IS Bleier3 and Gary Wind4

ISSN: 2378-3397 O’Donnell et al. Int J Surg Res Pract 2018, 5:079 DOI: 10.23937/2378-3397/1410079 Volume 5 | Issue 2 International Journal of Open Access Surgery Research and Practice CASE REPORT When a Case of Ulcerative Colitis Requires Mucosectomy and Hand-Sewn Ileo-Anal Pouch Anastomosis Mary Teresa M O’Donnell1,2*, Joshua IS Bleier3 and Gary Wind4 1Colon & Rectal Surgery Fellow, University of Pennsylvania, USA 2 Check for Assistant Professor of Surgery, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, USA updates 3Associate Professor of Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Pennsylvania, USA 4Professor of Surgery, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, USA *Corresponding author: Mary Teresa M O’Donnell, Colon & Rectal Surgery Fellow, ACS AEI Educational Fellow, University of Pennsylvania, USA; Assistant Professor of Surgery, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, USA, E-mail: [email protected] Summary who have undergone mucosectomy [4]. In addition, it is associated with increased risk of incontinence and Treatment of ulcerative colitis with total proctocol- operative difficulty. As a result, mucosectomy is rarely ectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) pro- performed. vides a near cure for the bowel component of ulcerative colitis, a restoration of bowel continuity, and the possi- Nevertheless, there are cases where mucosectomy and bility of normal defecation behaviors for patients. The hand-sewn ileal anal anastomosis may be required. If there majority of these procedures are carried out using end- are significant mucosal changes associated with ulcerative to-end circular stapling devices, which shorten surgery colitis that persist low in the rectum to the dentate line, times and have been shown to give better long-term the double-stapled anastomosis may be inadequate. -

Informed Consent for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

6930 Williams Road | Niagara Falls, NY 14304 | 716-284-3264 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Patient Name: MRN: DOB: Gender: Date: Physician: Procedure: ___________________________________________________________________________________ INFORMED CONSENT FOR GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY EXPLANATION OF PROCEDURE Direct visualization of the digestive tract with lighted instruments is referred to as gastrointestinal endoscopy. Your physician has advised you to have this type of examination. The following information is presented to help you understand the reasons for and the possible risks of these procedures. At the time of your examination, the lining of the digestive tract will be inspected thoroughly and possibly photographed. If an abnormality is seen or suspected, a small portion of tissue (biopsy) may be removed or the lining may be brushed. Small growths (polyps), if seen, may be removed. These samples are sent for laboratory study to determine if abnormal cells are present. If active bleeding is found, coagulation control by heat, medication, or mechanical clips may be performed. Moderate (Conscious) Sedation: Medications to keep you comfortable during the procedure may be given in the vein by the physician or a registered nurse directed by the physician to achieve conscious (or moderate) sedation. The medication could cause vein irritation, allergic reaction, cardiorespiratory depression or possible arrest. BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF ENDOSCOPIC PROCEDURES 1. EGD (Esophagogastroduodenoscopy): Examination of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. 2. Esophageal Dilation: Dilating tubes or balloons are used to stretch narrow areas of the esophagus. 3. EIS (Endoscopic Injection Sclerotherapy): Injection of a chemical into varices (dilated varicose veins of the esophagus) to sclerose (harden) the veins to prevent further bleeding. Injection is done with a small needle probe through the endoscope. -

BWH Gastroenterology

BWH 11/27/2017 1:58:45 PM Page 1 of 2 Gastroenterology Summary by Procedure From 11/28/2016 to 11/27/2017 Notes included: Submitted, Finalized, Addendum, Supervisor Override Procedure Number Percent Colonoscopy 4469 37.23 % Upper GI endoscopy 3981 33.16 % Upper EUS 693 5.77 % ERCP 651 5.42 % Flexible Sigmoidoscopy 575 4.79 % High Resolution esophageal manometry 439 3.66 % Ambulatory esophageal pH and impedance monitoring 343 2.86 % Video capsule endoscopy 235 1.96 % Anorectal manometry 152 1.27 % Small bowel enteroscopy 104 0.87 % Revision of Gastrojejunal Anastomosis, with endoscopic examination 78 0.65 % Pouchoscopy 61 0.51 % Lower EUS 38 0.32 % Upper Device-Assisted Enteroscopy without Fluoroscopy 33 0.27 % Esophageal BRAVO pH Capsule Results / Interpretation 32 0.27 % Post bypass enteroscopy 23 0.19 % Ileoscopy 21 0.17 % Necrosectomy 14 0.12 % Esophageal BRAVO pH Capsule Placement Only (No UGI Endoscopy) 13 0.11 % Non-endoscopic Tube Procedure 11 0.09 % Cricopharyngeal Myotomy with Zenker's Diverticulum Septal Ablation 10 0.08 % Lower Device-Assisted Enteroscopy with Fluoroscopy 6 0.05 % Upper Device-Assisted Enteroscopy with Fluoroscopy 5 0.04 % Lower Device-Assisted Enteroscopy without Fluoroscopy 4 0.03 % Colonoscopy via Stoma with Endoscopy of Hartmann Pouch 3 0.02 % Colonoscopy of Post-surgical Anatomy 3 0.02 % Helicobacter Pylori breath test 2 0.02 % Breath Test for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth 2 0.02 % Manometry (esophageal) 2 0.02 % DPEJ - Jejunal Tube 1 0.01 % Wireless Motility Capsule (SmartPill) 1 0.01 % Total 12005 -

Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan IRB00071015 NCT02049502 Title

Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan IRB00071015 NCT02049502 Title: The Use of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis-associated Pouchitis Principal Investigator: Virginia Shaffer, MD, Associate Professor of Surgery, Emory University School of Medicine Date 06/26/2017 FMT in UC-associated Pouchitis Version 3.0, date finalized 06/26/2017 1 Title: The Use of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis- associated Pouchitis Principal Investigator: Virginia Shaffer, MD, Associate Professor of Surgery, Emory University School of Medicine Emory University School of Medicine Divisions of Digestive Diseases and Infectious Diseases, Department of Surgery Research Protocol Title: The Use of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis- associated Pouchitis Principal Investigator: Virginia Shaffer, MD, Associate Professor of Surgery, Emory University School of Medicine 1. SPECIFIC AIMS The aims of this study are: 1) to determine the utility of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in the treatment of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) associated chronic antibiotic- dependent pouchitis (CADP) and chronic antibiotic refractory pouchitis (CARP) and 2) to study the changes in the microbial environment in patients with pouchitis (pre- and post- treatment) and 3) to assess the impact of therapy on the patient's perceived quality of life. 2. BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE The spectrum of inflammatory bowel diseases (lBO) includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD). The etiology of these diseases is not clear but appears to involve aberrant immunological responses to intestinal bacteria in a genetically predisposed host. There is increasing evidence that the intestinal microbiota play an important role in the initiation and maintenance of lBO. -

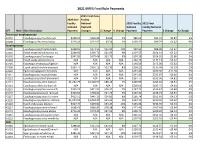

2021 MPFS Final Rule Payments

2021 MPFS Final Rule Payments 2021 Final Non- 2020 Non- Facility Facility National 2020 Facility 2021 Final National Payment National Facility National CPT Mod Short Descriptor Payment Changes $ Change % Change Payment Payment $ Change % Change Transnasal esophagoscopy 43197 Esophagoscopy flex dx brush $199.22 $203.08 $3.86 2% $86.62 $83.74 -$2.87 -3% 43198 Esophagosc flex trnsn biopy $219.43 $222.97 $3.54 2% $103.22 $99.79 -$3.42 -3% Esophagoscopy 43200 Esophagoscopy flexible brush $248.66 $273.56 $24.90 10% $90.95 $88.98 -$1.97 -2% 43201 Esoph scope w/submucous inj $248.66 $269.72 $21.06 8% $107.55 $104.33 -$3.22 -3% 43202 Esophagoscopy flex biopsy $347.91 $379.64 $31.73 9% $107.19 $104.33 -$2.86 -3% 43204 Esoph scope w/sclerosis inj N/A N/A N/A N/A $140.75 $137.13 -$3.62 -3% 43205 Esophagus endoscopy/ligation N/A N/A N/A N/A $146.89 $143.06 -$3.82 -3% 43206 Esoph optical endomicroscopy $293.77 $316.13 $22.36 8% $138.22 $135.04 -$3.19 -2% 43210 Egd esophagogastrc fndoplsty N/A N/A N/A N/A $451.49 $439.30 -$12.18 -3% 43211 Esophagoscop mucosal resect N/A N/A N/A N/A $244.33 $237.97 -$6.36 -3% 43212 Esophagoscop stent placement N/A N/A N/A N/A $197.77 $192.96 -$4.81 -2% 43213 Esophagoscopy retro balloon $1,262.79 $1,348.97 $86.18 7% $269.95 $263.44 -$6.51 -2% 43214 Esophagosc dilate balloon 30 N/A N/A N/A N/A $200.66 $195.75 -$4.91 -2% 43215 Esophagoscopy flex remove fb $395.19 $421.51 $26.32 7% $147.25 $143.41 -$3.84 -3% 43216 Esophagoscopy lesion removal $403.85 $438.61 $34.76 9% $139.31 $135.73 -$3.57 -3% 43217 Esophagoscopy snare -

Endoscopy Scheduling/Booking Form Date of Submission: Patient Data Name: Birth Date: Home Phone: Address: Sex: M F Other Phone: City: State: Zip: Religion

RIH Endoscopy Scheduling/Booking Form Date of Submission: Patient Data Name: Birth Date: Home phone: Address: Sex: M F Other phone: City: State: Zip: Religion: Procedure Information Interpreter Needed? Yes No Procedure Date: Ordering Physician: Language: Requested Time: Performing Physician: Pacemaker? Yes No *Leave date/time blank for Anesthesia cases PCP: External Defibrillator? Yes No Make/Serial# of Device: Dx Codes ICD10: Description: ICD10: Description: ICD10: Description: ICD10: Description: Procedure: Asterisk (*) indicates a Medicare Advanced Beneficiary Notice (ABN) may be needed if ordered test/procedure is not covered by applicable ICD codes/Dx. Check RI Medicare Local Medicare Review Policy for coverage information **Requires Additional Requisition Form M2A Capsule Endoscopy** (91110) Change of G tube (43760) Colon* (45378) 24-Hour pH Monitor** (91034) EGD (43235) Screen colon average risk* (G0121) Bravo 24-Hour pH Capsule** (91035) EGD w/Esophageal Motility (43241) Date of last exam: Bravo 48-Hour pH Capsule** EGD w/PEG (43246) Screen colon high risk* (G0105) Impedence 24-Hour pH Probe (91038) EGD w/Stent Placement (43266) Date of last exam: Esophageal Motility (91010) EGD w/Ablation (43270) Barrx Cryo Colon w/Stent Placement* (45387) Esophageal Motility w/Impedence (91037) EGD w/Ultrasound (43259) Stool Transplant (44705) EGD w/US FNA (43242) Need Cytology Retro Colon (44799) ECHO Transrectal Ultrasound (76872) EGD w/EMR (43254) EA Motor Nerve w/o Wave Study (95907) ERCP (43260) EMG -

Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute

Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute This project would not have been possible without the commitment and expertise of a team led by Laura Buccini, DrPH, MPH. Graphic design and photography were provided by Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Medical Art and Photography. © The Cleveland Clinic Foundation 2017 9500 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44195 clevelandclinic.org 2016 Outcomes 17-OUT-416 108371_CCFBCH_17OUT416_ACG.indd 1-3 8/31/17 12:54 PM Measuring Outcomes Promotes Quality Improvement Clinical Trials Cleveland Clinic is running more than 2200 clinical trials at any given time for conditions including breast and liver cancer, coronary artery disease, heart failure, epilepsy, Parkinson disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, high blood pressure, diabetes, depression, and eating disorders. Cancer Clinical Trials is a mobile app that provides information on the more than 200 active clinical trials available to cancer patients at Cleveland Clinic. clevelandclinic.org/cancertrialapp Healthcare Executive Education Cleveland Clinic has programs to share its expertise in operating a successful major medical center. The Executive Visitors’ Program is an intensive, 3-day behind-the-scenes view of the Cleveland Clinic organization for the busy executive. The Samson Global Leadership Academy is a 2-week immersion in challenges of leadership, management, and innovation taught by Cleveland Clinic leaders, administrators, and clinicians. Curriculum includes coaching and a personalized 3-year leadership development plan. clevelandclinic.org/executiveeducation Consult QD Physician Blog A website from Cleveland Clinic for physicians and healthcare professionals. Discover the latest research insights, innovations, treatment trends, and more for all specialties. consultqd.clevelandclinic.org Social Media Cleveland Clinic uses social media to help caregivers everywhere provide better patient care. -

Recurrent Ileal J Pouch Volvulus

ACS Case Reviews in Surgery Vol. 2, No. 5 Recurrent Ileal J Pouch Volvulus AUTHORS: CORRESPONDENCE AUTHOR: Gabrielle M. Perrotti, BA; Omar Marar, MD; Gabrielle Perrotti Benjamin R. Phillips MD, FACS, FASCRS 25 Pollari Circle Newark, DE 19702 Phone: 302-530-9305 Email: [email protected] Background For refractory ulcerative colitis (UC), total proctocolectomy (TP) with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) is the operative treatment of choice. Unfortunately, there are numerous complications that are unique to patients with an IPAA. Pouch volvulus represents one of the rarer complications encountered in the post-operative period. We present the case of a recurrent pouch volvulus treated with pouch pexy and absorbable mesh placement. Summary This patient is a 40-year-old female with a history of refractory ulcerative colitis who is status post 3-stage total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. A year after the reversal of the loop ileostomy she presented to the emergency room with obstipation, nausea, and vomiting. Work-up was suspicious for pouch volvulus. She was taken to the operating room and underwent laparoscopic detorsion of the pouch with pouch pexy. A year later, the patient presented to the emergency department with similar symptoms and CT scan along with pouchoscopy revealed recurrent torsion of the pouch. We present a rare case of recurrent pouch volvulus and its successful management by laparoscopic detorsion with pouch pexy and presacral absorbable mesh placement. Conclusion Volvulus is a rare complication of an IPAA. Successful management during the initial procedure is important to prevent recurrence and its sequelae. We recommend deliberate and meticulous obliteration of the defect between the ileal mesentery and the sacral promontory to prevent internal herniation and recurrence of the volvulus.