Syrian and Iraqi Citizen Journalists Versus the Islamic State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Same Breath

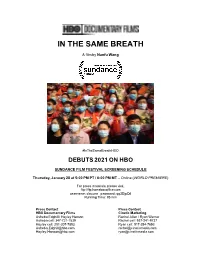

IN THE SAME BREATH A film by Nanfu Wang #InTheSameBreathHBO DEBUTS 2021 ON HBO SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL SCREENING SCHEDULE Thursday, January 28 at 5:00 PM PT / 6:00 PM MT – Online (WORLD PREMIERE) For press materials, please visit: ftp://ftp.homeboxoffice.com username: documr password: qq3DjpQ4 Running Time: 95 min Press Contact Press Contact HBO Documentary Films Cinetic Marketing Asheba Edghill / Hayley Hanson Rachel Allen / Ryan Werner Asheba cell: 347-721-1539 Rachel cell: 937-241-9737 Hayley cell: 201-207-7853 Ryan cell: 917-254-7653 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LOGLINE Nanfu Wang's deeply personal IN THE SAME BREATH recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. SHORT SYNOPSIS IN THE SAME BREATH, directed by Nanfu Wang (“One Child Nation”), recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. In a deeply personal approach, Wang, who was born in China and now lives in the United States, explores the parallel campaigns of misinformation waged by leadership and the devastating impact on citizens of both countries. Emotional first-hand accounts and startling, on-the-ground footage weave a revelatory picture of cover-ups and misinformation while also highlighting the strength and resilience of the healthcare workers, activists and family members who risked everything to communicate the truth. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I spent a lot of my childhood in hospitals taking care of my father, who had rheumatic heart disease. -

The Look of Silence and Last Day of Freedom Take Top Honors at the 2015 IDA Documentary Association Awards

Amy Grey / Ashley Mariner Phone: 818-508-1000 Dish Communications [email protected] / [email protected] The Look of Silence and Last Day of Freedom Take Top Honors at the 2015 IDA Documentary Association Awards Best of Enemies, Listen to Me Marlon & HBO’s The Jinx Also Pick Up Awards LOS ANGELES, December 5, 2015 – Winners in the International Documentary Association’s 2015 IDA Documentary Awards were announced during tonight’s program at the Paramount Theatre, giving Joshua Oppenheimer’s THE LOOK OF SILENCE top honors with the Best Feature Award. This critically acclaimed, powerful companion piece to the Oscar®-nominated The Act of Killing, follows a family of survivors of the Indonesian genocide who discover how their son was murdered and the identities of the killers. Also announced in the ceremony was the Best Short Award, which honored LAST DAY OF FREEDOM, directed by Dee Hibbert-Jones and Nomi Talisman. The film is an animated account of Bill Babbitt’s decision to support and help his brother in the face of war, crime and capital execution. Grammy-nominated comedian Tig Notaro hosted the ceremony, which gathered the documentary community to honor the best nonfiction films and programming of 2015. IDA’s Career Achievement Award was presented to Gordon Quinn, Founder and Artistic Director of Kartemquin Films. He has produced, directed and/or been cinematographer on over 55 films across five decades. A longtime activist for public and community media, Quinn was integral to the creation of ITVS, public access television in Chicago; in developing the Documentary Filmmakers Statement of Best Practice in Fair Use; and in forming the Indie Caucus to support diverse independent voices on Public Television. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

![Bibliography: Islamic State (IS, ISIS, ISIL, Daesh) [Part 5]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9484/bibliography-islamic-state-is-isis-isil-daesh-part-5-659484.webp)

Bibliography: Islamic State (IS, ISIS, ISIL, Daesh) [Part 5]

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 13, Issue 3 Resources Bibliography: Islamic State (IS, ISIS, ISIL, Daesh) [Part 5] Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes [Bibliographic Series of Perspectives on Terrorism – BSPT-JT-2019-4] Abstract This bibliography contains journal articles, book chapters, books, edited volumes, theses, grey literature, bibliogra- phies and other resources on the Islamic State (IS / ISIS / ISIL / Daesh) and its predecessor organizations. To keep up with the rapidly changing political events, the most recent publications have been prioritized during the selec- tion process. The literature has been retrieved by manually browsing through more than 200 core and periphery sources in the field of Terrorism Studies. Additionally, full-text and reference retrieval systems have been employed to broaden the search. Keywords: bibliography, resources, literature, Islamic State; IS; ISIS; ISIL; Daesh; Al-Qaeda in Iraq; AQI NB: All websites were last visited on 18.05.2019. This subject bibliography is conceptualised as a multi-part series (for earlier bibliog- raphies, see: Part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3 , and Part 4). To avoid duplication, this compilation only includes literature not contained in the previous parts. However, meta-resources, such as bibliographies, were also included in the sequels. – See also Note for the Reader at the end of this literature list. Bibliographies and other Resources Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) (2014, November-): Thematic Dossier XV: Daesh in Afghanistan. URL: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/publication/aan-thematic-dossier/thematic-dossier-xv-daesh-in-af- ghanistan Al-Khalidi, Ashraf; Renahan, Thomas (Eds.) (2015, May-): Daesh Daily: An Update On ISIS Activities. URL: http://www.daeshdaily.com Al-Tamimi, Aymenn Jawad (2010-): [Homepage]. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

For Immediate Release Tribeca Film Festival® Announces

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL® ANNOUNCES FEATURE FILM LINE UP FOR THE COMPETITION, SPOTLIGHT, VIEWPOINTS AND MIDNIGHT SECTIONS OF THE 16TH ANNUAL FESTIVAL APRIL 19-30 ProgrAm Includes Artistic Gems, Comedies, Complex Artistic PortrAits, And PoliticAl And Social Action Films that will Engage, Inspire and Entertain New York, NY [MArch 2, 2017] – An exciting slate of films that showcases the breadth of contemporary filmmaking across a range of styles will premiere at the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival, presented by AT&T. The Festival today announced the feature films across the following programs: Competition, including U.S. Narrative, Documentary, and International Narrative categories; Spotlight, supported by The Lincoln Motor Company, a selection of anticipated premieres from major talent; Viewpoints, which recognizes distinct voices in international and American independent filmmaking; and the popular Midnight Section, supported by EFFEN® Vodka, featuring the best in psychological thriller, horror, sci-fi, and cult cinema. After receiving a record number of entries, the Festival’s seasoned team of programmers, led by Cara Cusumano in her new role as Director of Programming and Artistic Director Frédéric Boyer, carefully curated an edgy, entertaining and provocative program. The 16th Annual Tribeca Film Festival takes place April 19 – 30. Today’s announcement includes 82 of the 98 feature-length titles in the Festival. In a year of record high submissions, the Festival’s curators chose to reduce the size of the overall program by 20%, making this the most selective and focused festival slate yet. The Competition section features 32 films: 12 documentaries, 10 U.S. narratives and 10 international narratives. -

Journey to the Academy Awards: an Investigation of Oscar-Shortlisted and Nominated Documentaries (2014-2016) PRELIMINARY KEY

Journey to the Academy Awards: An Investigation of Oscar-Shortlisted and Nominated Documentaries (2014-2016) PRELIMINARY KEY FINDINGS By Caty Borum Chattoo, Co-Director, Center for Media & Social Impact American University School of Communication | Washington, D.C. February 2016 OVERVIEW For a documentary filmmaker, being recognized by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences for an Oscar nomination in the Best Documentary Feature category is often the pinnacle moment in a career. Beyond the celebratory achievement, the acknowledgment can open up doors for funding and opportunities for next films and career opportunities. The formal recognition happens in three phases: It begins in December with the Academy’s announcement of a shortlist—15 films that advance to a formal nomination for the Academy’s Best Documentary Feature Award. Then, in mid-January, the final list of five official nominations is announced. Finally, at the end of February each year, the one winner is announced at the Academy Awards ceremony. Beyond a film’s narrative and technical prowess, the marketing campaigns that help a documentary make it to the shortlist and then the final nomination list are increasingly expensive and insular, from advertisements in entertainment trade outlets to lavish events to build buzz among Academy members and industry influencers. What does it take for a documentary film and its director and producer to make it to the top—the Oscars shortlist, the nomination and the win? Which film directors are recognized—in terms of race and gender? -

Journey to the Academy Awards: an Investigation of Oscar-Shortlisted and Nominated Documentaries (2014-2016)

Journey to the Academy Awards: An Investigation of Oscar-Shortlisted and Nominated Documentaries (2014-2016) PRELIMINARY KEY FINDINGS By Caty Borum Chattoo, Co-Director, Center for Media & Social Impact American University School of Communication | Washington, D.C. February 2016 OVERVIEW For a documentary filmmaker, being recognized by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences for an Oscar nomination in the Best Documentary Feature category is often the pinnacle moment in a career. Beyond the celebratory achievement, the acknowledgment can open up doors for funding and opportunities for next films and career opportunities. The formal recognition happens in three phases: It begins in December with the Academy’s announcement of a shortlist—15 films that advance to a formal nomination for the Academy’s Best Documentary Feature Award. Then, in mid-January, the final list of five official nominations is announced. Finally, at the end of February each year, the one winner is announced at the Academy Awards ceremony. Beyond a film’s narrative and technical prowess, the marketing campaigns that help a documentary make it to the shortlist and then the final nomination list are increasingly expensive and insular, from advertisements in entertainment trade outlets to lavish events to build buzz among Academy members and industry influencers. What does it take for a documentary film and its director and producer to make it to the top—the Oscars shortlist, the nomination and the win? Which film directors are recognized—in terms of race and gender? -

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2015 Our Work 08

ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2015 OUR WORK 08 ARTIST SUPPORT 11 PUBLIC PROGRAMS 35 TRANSFORMATIVE SUPPORT 42 INSTITUTIONAL HEALTH 44 FOCUS ON THE ARTIST 45 2 “ There will always be new terrain to explore as long as there are artists willing to take risks, who tell their stories without compromise. And Sundance will be here - to provide a range of support and a creative community in which a new idea or distinctive view is championed.” ROBERT REDFORD PRESIDENT AND FOUNDER Nia DaCosta and Robert Redford, Little Woods, 2015 Directors Lab, Photo by Brandon Cruz SUNDANCE INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT 2015 3 WELCOME ROBERT REDFORD PRESIDENT AND FOUNDER PAT MITCHELL CHAIR, BOARD OF TRUSTEES KERI PUTNAM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR I also want to thank the nearly 750 independent artists who As we close another year spent supporting extraordinary shared their work with us last year. We supported them Sundance Institute offers an environment and opportunities The health, vitality, and diversity of the Institute’s year-round artists and sharing their work with audiences around the through our 25 residency Labs, provided direct grants for artists to take risks, experiment, and fail without fear. programs are a testament to both the independent artists world, it is my pleasure to share with you the Sundance of nearly $3 million, awarded fellowships and structured We see failure not as an end but as an essential step in the who are inspired to tell their unique stories as well as the Institute Annual Report — filled with insight into the nature mentorship, and of course celebrated and launched their road. -

The Cleaners a Documentary By

THE CLEANERS A DOCUMENTARY BY HANS BLOCK & MORITZ RIESEWIECK Official selection Geneva International film festival and forum on human rights 2018 88 MIN 2018 GERMANY, BRAZIL CONTENTS CONTENTS CONTACTS 03 CREDITS 04 SYNOPSIS 5-6 DIRECTOR´S NOTES 7-8 PRESS REVIEWS 09 CONTENT MODERATORS 10-11 SILICON VALLEY 12 SECONDARY CHARACTERS 13-15 EXPERTS 15 FILMMAKER BIOS 16-20 PRODUCTION COMPANIES 21-22 02 CONTACTS Publicity Contact US Sales Contact Int‘l Sales Contact Production company Nina Hölzl Submarine - Josh Braun Cinephil gebrueder beetz gebrueder beetz [email protected] Philippa Kowarsky filmproduktion filmproduktion 212 625 1410 [email protected] [email protected] n.hoelzl@ c: 917 687 311 +972 3 566 4129 www.beetz-brothers.de gebrueder-beetz.de +49 (0)30 695 669 14 03 CREDITS CREDITS DIRECTORS MUSIC CO-PRODUCERS LINE PRODUCER Hans Block John Gürtler, Jan Miserre Fernando Dias Kathrin Isberner Moritz Riesewieck and Lars Voges Mauricio Dias Reinhardt Beetz PRODUCTION MANAGER Andrea Romeo DIRECTORS OF PRODUCER Anique Roelfsema PHOTOGRAPHY Georg Tschurtschenthaler PRODUCED BY Axel Schneppat and PRODUCTION COMPANIES Max Preiss Christian Beetz EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS gebrueder beetz filmproduktion Christopher Clements ASSOCIATE PRODUCERS SOUND Julie Goldman Grifa Filmes Zora Nessl Karsten Höfer Philippa Kowarsky Motto Pictures Marissa Ericson CO-EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS EDITORS POST-PRODUCTION Philipp Gromov Carolyn Hepburn MANAGER Hansjörg Weißbrich Neil Tabatzink Xavier Agudo Markus CM Schmidt Robin Smith A gebrueder beetz filmproduktion -

Paul Conroy on Marie Colvin and the Personal Cost of Covering War

Donate February 2019 PAUL CONROY ON MARIE COLVIN AND THE PERSONAL COST OF COVERING WAR 04/02/19 Written by Molly Clarke with Sophie Baggott Photo: Paul Conroy On 31 January 2019, a US court found Syria’s Assad regime responsible for the murder of renowned Sunday Times journalist Marie Colvin in 2012. As a feature film about Marie goes on release in the UK, we spoke with its director Matthew Heineman and freelance photographer Paul Conroy – Marie’s close friend and colleague – about the personal cost of covering conflict and the importance of telling Marie’s story at a time when journalists are increasingly coming under attack. In her landmark ruling last week, US District Judge Amy Berman Jackson said Marie was “specifically targeted because of her profession, for the purpose of silencing those reporting on the growing opposition movement in the country", adding that “The murder of journalists acting in their professional capacity could have a chilling effect on reporting such events worldwide”. For Paul Conroy, the ruling is a vindication. He sustained severe injuries in the explosion that killed Marie and French freelance photographer Rémi Ochlik in the city of Homs on 22 February 2012. With his expertise as a former soldier with the Royal Artillery, Paul has always argued that the way in which the bombs closed in on the makeshift media centre revealed that the Syrian army was pinpointing its target. Marie had made broadcasts to the BBC, Channel 4 and CNN from the centre, telling them that the bombing of Homs was slaughtering civilians, not terrorists. -

City of Ghosts Free

FREE CITY OF GHOSTS PDF Stacia Kane | 408 pages | 27 Jul 2010 | Random House USA Inc | 9780345515599 | English | New York, United States City of Ghosts - Wikipedia Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to City of Ghosts. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. City of Ghosts — City of Ghosts by Victoria Schwab. Cassidy Blake's parents are The Inspecters, a somewhat inept ghost-hunting team. In fact, her best friend, Jacob, just happens to be one. In Scotland, Cass is surrounded by ghosts, not all of them friendly. Then she meets Cassidy Blake's parents are The Inspecters, a somewhat inept ghost-hunting team. Then she meets Lara, a girl who can also see the dead. But Lara tells Cassidy that City of Ghosts an In-betweener, their job is to send ghosts permanently beyond the Veil. Cass isn't sure about her new mission, but she does know the sinister Red Raven haunting the City of Ghosts doesn't belong in her world. Cassidy's powers will draw her into an epic fight that stretches through the worlds of the living and the dead, in order to save herself. Get A Copy. More Details Original Title. Cassidy Blake 1. Edinburgh, Scotland Scotland. Other Editions Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about City of Ghostsplease sign up.