Five Border Arrondissements Around Brussels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overzicht Hinder Voor Dienstverlening

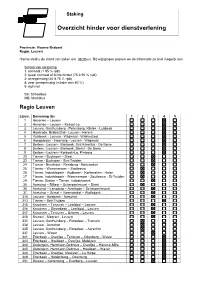

Staking Overzicht hinder voor dienstverlening Provincie: Vlaams-Brabant Regio: Leuven Hierna vindt u de stand van zaken om 06.00uur. Bij wijzigingen passen we de informatie zo snel mogelijk aan. Schaal van verstoring 1: normaal (+ 95 % rijdt) 2: quasi normaal of lichte hinder (75 à 95 % rijdt) 3: onregelmatig (40 à 75 % rijdt) 4: zeer onregelmatig (minder dan 40 %) 5: rijdt niet SB: Schoolbus MB: Marktbus Regio Leuven Lijnnr. Benaming lijn 1 2 3 4 5 1 Heverlee – Leuven 2 Heverlee – Leuven – Kessel-Lo 3 Leuven, Gasthuisberg - Pellenberg, Kliniek - Lubbeek 4 Haasrode, Brabanthal - Leuven - Herent 5 Vaalbeek - Leuven - Wijgmaal - Wakkerzeel 6 Hoegaarden - Neervelp - Leuven - Wijgmaal 7 Bertem - Leuven - Bierbeek, Sint-Kamillus - De Borre 8 Bertem - Leuven - Bierbeek, Bremt - De Borre 9 Bertem - Leuven - Korbeek-Lo, Pimberg 22 Tienen – Budingen – Diest 23 Tienen - Budingen - Sint-Truiden 24 Tienen - Neerlinter - Ransberg - Kortenaken 25 Tienen – Wommersom – Zoutleeuw 26 Tienen, Industriepark - Budingen - Kortenaken - Halen 27 Tienen, Industriepark - Wommersom - Zoutleeuw - St-Truiden 29 Tienen, Station – Tienen, Industriepark 35 Aarschot – Rillaar – Scherpenheuvel – Diest 36 Aarschot – Langdorp – Averbode – Scherpenheuvel 37 Aarschot – Gijmel – Varenwinkel – Wolfsdonk 310 Leuven - Holsbeek - Aarschot 313 Tienen – Sint-Truiden 315 Kraainem – Tervuren – Leefdaal – Leuven 316 Kraainem – Sterrebeek – Leefdaal – Leuven 317 Kraainem – Tervuren – Bertem – Leuven 318 Brussel - Moorsel - Leuven 333 Leuven, Gasthuisberg – Rotselaar – Tremelo 334 Leuven -

Une «Flamandisation» De Bruxelles?

Une «flamandisation» de Bruxelles? Alice Romainville Université Libre de Bruxelles RÉSUMÉ Les médias francophones, en couvrant l'actualité politique bruxelloise et à la faveur des (très médiatisés) «conflits» communautaires, évoquent régulièrement les volontés du pouvoir flamand de (re)conquérir Bruxelles, voire une véritable «flamandisation» de la ville. Cet article tente d'éclairer cette question de manière empirique à l'aide de diffé- rents «indicateurs» de la présence flamande à Bruxelles. L'analyse des migrations entre la Flandre, la Wallonie et Bruxelles ces vingt dernières années montre que la population néerlandophone de Bruxelles n'est pas en augmentation. D'autres éléments doivent donc être trouvés pour expliquer ce sentiment d'une présence flamande accrue. Une étude plus poussée des migrations montre une concentration vers le centre de Bruxelles des migrations depuis la Flandre, et les investissements de la Communauté flamande sont également, dans beaucoup de domaines, concentrés dans le centre-ville. On observe en réalité, à défaut d'une véritable «flamandisation», une augmentation de la visibilité de la communauté flamande, à la fois en tant que groupe de population et en tant qu'institution politique. Le «mythe de la flamandisation» prend essence dans cette visibilité accrue, mais aussi dans les réactions francophones à cette visibilité. L'article analyse, au passage, les différentes formes que prend la présence institutionnelle fla- mande dans l'espace urbain, et en particulier dans le domaine culturel, lequel présente à Bruxelles des enjeux particuliers. MOTS-CLÉS: Bruxelles, Communautés, flamandisation, migrations, visibilité, culture ABSTRACT DOES «FLEMISHISATION» THREATEN BRUSSELS? French-speaking media, when covering Brussels' political events, especially on the occasion of (much mediatised) inter-community conflicts, regularly mention the Flemish authorities' will to (re)conquer Brussels, if not a true «flemishisation» of the city. -

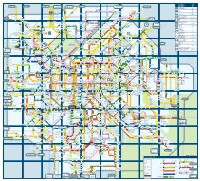

Overzichtskaart

Overzichtskaart Plechtige opening busstation Vilvoorde, 12 januari 2017 - De werkzaamheden zijn begonnen op 19 april 2016 en waren - zoals gepland - eind december voltooid . - Het project vertegenwoordigt een investering van zo’n 2,7 miljoen euro . Daarvan 2,2 miljoen euro voor de aankoop van het Joker Casino, 490 000 euro voor de bouw van de busterminal. - Het nieuwe busstation telt zes perrons die bediend worden door 15 buslijnen van De Lijn en 2 buslijnen van de MIVB . - Per dag zijn er in het busstation van Vilvoorde zo’n 5 000 op- en afstappers . Vijftien buslijnen van De Lijn en twee buslijnen van de MIVB verbinden het busstation van Vilvoorde met de ruime omgeving. Er zijn lijnen naar onder meer Mechelen en Grimbergen en enkele economische attractiepolen zoals de luchthaven van Zaventem. De volgende buslijnen van De Lijn bedienen het station van Vilvoorde: bus lijn 218 Vilvoorde - Peutie bus lijn 221 Vilvoorde - Steenokkerzeel (marktbus) bus lijn 222 Vilvoorde - Zaventem bus lijn 225 Vilvoorde - Kortenberg bus lijn 261 Vilvoorde - Londerzeel bus lijn 280 Vilvoorde - Mechelen bus lijn 282 Mechelen - Zaventem bus lijn 287 Vilvoorde - Houtem bus lijn 533 Vilvoorde - Kapelle-op-den-Bos bus lijn 536 Vilvoorde - Grimbergen bus lijn 538 Vilvoorde - Diegem Lo - Zaventem Atheneum bus lijn 621 Vilvoorde - Zaventem bus lijn 683 Zaventem - Vilvoorde - Zemst - Mechelen bus lijn 820 Zaventem - Dilbeek bus lijn 821 Zaventem – Merchtem Daarnaast hebben ook bussen 47 en 58 van de Brusselse vervoermaatschappij MIVB hun eindhalte aan het busstation van Vilvoorde. De volgende partners waren betrokken bij de aanleg van het busstation en de omgeving (in alfabetische volgorde): Agentschap Wegen en Verkeer – MIVB – NMBS – Stad Vilvoorde - Wegebo/Colas (aannemer) Overzichtskaart Plechtige opening busstation Vilvoorde, 12 januari 2017 . -

Public Fisheries Regulations 2018

FISHINGIN ACCORDANCE WITH THE LAW Public Fisheries Regulations 2018 ATTENTION! Consult the website of the ‘Agentschap voor Natuur en Bos’ (Nature and Forest Agency) for the full legislation and recent information. www.natuurenbos.be/visserij When and how can you fish? Night fishing To protect fish stocks there are two types of measures: Night fishing: fishing from two hours after sunset until two hours before sunrise. A large • Periods in which you may not fish for certain fish species. fishing permit of € 45.86 is mandatory! • Ecologically valuable waters where fishing is prohibited in certain periods. Night fishing is prohibited in the ecologically valuable waters listed on p. 4-5! Night fishing is in principle permitted in the other waters not listed on p. 4-5. April Please note: The owner or water manager can restrict access to a stretch of water by imposing local access rules so that night fishing is not possible. In some waters you might January February March 1 > 15 16 > 30 May June July August September October November December also need an explicit permit from the owner to fish there. Fishing for trout x x √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ x x x Fishing for pike and Special conditions for night fishing √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ pikeperch Always put each fish you have caught immediately and carefully back into the water of origin. The use of keepnets or other storage gear is prohibited. Fishing for other √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ species You may not keep any fish in your possession, not even if you caught that fish outside the night fishing period. Night fishing √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ Bobber fishing √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ Wading fishing x x √ √ x x √ √ √ √ √ √ x x x x Permitted x Prohibited √ Prohibited in the waters listed on p. -

Kanaal Leuven-Dijle Lengte : 30,043 Km Max

update: september 2009 Technische gegevens Kanaal Leuven-Dijle Lengte : 30,043 km Max. toegelaten afmetingen van de schepen : 51,70 x 7,55 m (mits vergunning grotere afmetingen toegelaten max. 55 x 7,50 m tot Battel) Diepgang (DG) : 2,30 m Vrije hoogte (VH) : 6,00 m Klasse DG VH oorsprong te Leuven tot en met de Zennegatsluis II 2,30 6,00 afwaarts de Zennegatsluis tot verbinding Beneden-Dijle (tij) II veranderlijk* ** Laad- en losplaatsen : Gemeente Oever Kmp Lengte(m) Eigenaar Uitrusting Gebruik Leuven (AB Inbev) Ro 0,44 300 Privé zuiginstallatie P Leuven (Vaartkom) Lo 0,44 100 Gewest geen O Leuven (Cervo) Ro 0,74 32 Privé zuiginstallatie P Wilsele (Kumps) Ro 1,12 16 Privé zuiginstallatie P Wilsele (De Stordeur) Ro 1,82 30 Privé zuiginstallatie N Wilsele (Wegebo) Lo 1,87 70 Privé mob kraan N Wilsele (Vlabraver) Ro 2 Gewest in aanbouw Wijgmaal (Remy Products) Ro 4,145 36 Privé zuiginstallatie P Herent (Cargill) Lo 6,045 120 Gewest in renovatie Tildonk (Trebos) Ro 7,5 18 Privé geen N Kampenhout (M&W Beton) Ro 12 Gewest in aanbouw Kampenhout (zwaaikom) Ro 12,863 200 Gewest geen O Boortmeerbeek (Boortmalt) Ro 14,73 110 Privé zuiginstallatie P Boortmeerbeek (Cobema) Ro 15,383 70 Privé geen N Hofstade (ABI Beton) Ro 18,76 91 Privé geen N Mechelen (Omato) Ro 22,674 575 Gewest geen O Mechelen (Battel) Ro 26,92 300 Gewest geen O Mechelen (Zennegat) Ro 28,343 250 Gewest geen O Tel.nrs. sluizen : Sluis Tildonk : 016/60.11.63 Sluis Kampenhout : 016/60.16.73 Sluis Boortmeerbeek : 015/51.11.67 Sluis Battel : 015/27.12.60 Sluis Zennegat : 015/27.12.57 Beheerder : Waterwegen en Zeekanaal NV, Afdeling Zeekanaal Oostdijk 110 2830 Willebroek Tel.: 03/886.80.86 Fax: 03/886.21.98 Legende bij technische fiches waterwegen VH: vrije hoogte. -

Memorandum Vlaamse En Federale

MEMORANDUM VOOR VLAAMSE EN FEDERALE REGERING INLEIDING De burgemeesters van de 35 gemeenten van Halle-Vilvoorde hebben, samen met de gedeputeerden, op 25 februari 2015 het startschot gegeven aan het ‘Toekomstforum Halle-Vilvoorde’. Toekomstforum stelt zich tot doel om, zonder bevoegdheidsoverdracht, de kwaliteit van het leven voor de 620.000 inwoners van Halle-Vilvoorde te verhogen. Toekomstforum is een overleg- en coördinatieplatform voor de streek. We formuleren in dit memorandum een aantal urgente vragen voor de hogere overheden. We doen een oproep aan alle politieke partijen om de voorstellen op te nemen in hun programma met het oog op het Vlaamse en federale regeerprogramma in de volgende legislatuur. Het memorandum werd op 19 december 2018 voorgelegd aan de burgemeesters van de steden en gemeenten van Halle-Vilvoorde en door hen goedgekeurd. 1. HALLE-VILVOORDE IS EEN CENTRUMREGIO Begin 2018 hebben we het dossier ‘Centrumregio-erkenning voor Vlaamse Rand en Halle’ met geactualiseerde cijfers gepubliceerd (zie bijlage 1). De analyse van de cijfers toont zwart op wit aan dat Vilvoorde, Halle en de brede Vlaamse Rand geconfronteerd worden met (groot)stedelijke problematieken, vaak zelfs sterker dan in andere centrumsteden van Vlaanderen. Momenteel is er slechts een beperkte compensatie voor de steden Vilvoorde en Halle en voor de gemeente Dilbeek. Dat is positief, maar het is niet voldoende om de problematiek, met uitlopers over het hele grondgebied van het arrondissement, aan te pakken. Toekomstforum Halle-Vilvoorde vraagt een erkenning van Halle-Vilvoorde als centrumregio. Deze erkenning zien we als een belangrijk politiek signaal inzake de specifieke positie van Halle-Vilvoorde. De erkenning als centrumregio moet extra financiering aanreiken waarmee de lokale besturen van de brede Vlaamse rand projecten en acties kunnen opzetten die de (groot)stedelijke problematieken aanpakken. -

Contactgegevens Gemeente Kampenhout Gemeentehuisstraat 16 - 1910 Kampenhout 016/65 99 11 [email protected]

Providentia cvba met sociaal oogmerk Burgerlijke vennootschap die de vorm van een handelsvennootschap heeft aangenomen bij de rechtbank van koophandel te Brussel, nr 97 Sociale huisvestingsmaatschappij door de VMSW erkend onder nr 222/8. Brusselsesteenweg 191 - 1730 Asse Bezoekdagen : maandag, woensdag en vrijdag van 8 tot 11.30 uur Contactgegevens gemeente Kampenhout Gemeentehuisstraat 16 - 1910 Kampenhout 016/65 99 11 [email protected] www.kampenhout.be Medische spoedgevallen Politiezone KASTZE Politiezone KASTZE 112 Hoofdkantoor Wijkkantoor Kampenhout Brandweer Tervuursesteenweg 295 Gemeentehuisstraat 16 112 1820 Steenokkerzeel 1910 Kampenhout Dringende politiehulp 02/759 78 72 016/31 48 40 101 [email protected] www.kastze.be [email protected] Centrum Algemeen Welzijn JAC Inloop- ontmoetingscentrum (CAW) (jongerenwerking CAW) Komma Binnen (CAW) J.Baptiste Nowélei 33 J.Baptiste Nowélei 33 Mechelsesteenweg 55 1800 Vilvoorde 1800 Vilvoorde 1800 Vilvoorde 02/613 17 00 02/613 17 02 02/613 17 00 www.caw.be www.jac.be www.caw.be www.caw.be/chat www.jac.be/chat [email protected] [email protected] OCMW Kampenhout RVA-kantoor Vilvoorde VDAB Vilvoorde Dorpsstraat 9 Leopoldstraat 25 - Bus A Witherenstraat 19 1910 Kampenhout 1800 Vilvoorde 1800 Vilvoorde 016/31 43 10 www.rva.be/nl/kantoren/rva- 0800/30 700 - 02/254 73 00 kantoor-vilvoorde www.vdab.be [email protected] [email protected] Bureau juridische bijstand Huurdersbond Burenbemiddeling Gerechtsgebouw Vlaams-brabant - Leuven Regenschapsstraat 63 - B1 Tiensevest -

De Zwalpende

RANDKRANT FR · DE · EN traductions Maandblad over de Vlaamse Rand · december 2020 · jaar 24 · #09 Übersetzungen translations Kinderrechtencommissaris Caroline Vrijens ‘Kinderarmoede bestrijden, moet topprioriteit zijn’ Meer veerkracht voor het onderwijs in de Rand Psychiater Dirk Olemans ‘Er is een uitputtingsslag aan de gang’ Fotograaf Turjoy Chowdhury ‘De mensheid redden, is onze verantwoordelijkheid’ FOTO: FILIP CLAESSENS FOTO: • Wat loopt er scheef bij De Lijn? De zwalpende bus 1 VERSCHIJNT NIET IN JANUARI, JULI EN AUGUSTUS NIET IN JANUARI, VERSCHIJNT DEKETTING INHOUD Stijn Mertens (42) uit Grimbergen werd vorige maand door Femke DE Duquet aangeduid om deketting voort te zetten. Mertens komt uit een ondernemersfamilie en baat een fietsenhandel uit. Alles loopt op wieltjes FR e familie Mertens heeft iets met naar fietsen heel sterk toegenomen. De wielen. Stijn Mertens: ‘Ik ben fabrikanten kunnen de fietsen zelfs niet op opgegroeid in Wolvertem. Na mijn tijd leveren. Ik geef voorrang aan mijn eigen D studies ging ik als mecanicien klanten voor het onderhoud van hun fiets. werken in het autocenter van mijn vader. Het orderboekje zit al weken op voorhand vol. Onze familie is al verschillende generaties Vandaag werken we op afspraak. We komen actief in de auto mobielsector. In 1930 richtte handen tekort.’ Alfons Mertens aan de Beigemsesteenweg in Grimbergen een garage op. Zijn zoon Frans Fietsen steeds populairder – mijn grootvader – begon er in 1955 met de ‘De trend van steeds meer fietsen is positief verdeling van Fiat en startte in Nieuwenrode en mag zich voortzetten. Mensen zijn de files een carrosserie centrum. Zijn zonen Robert beu en kiezen voor de fiets als alternatief. -

Uw Gemeente in Cijfers: Huldenberg

Uw gemeente in cijfers: Huldenberg Uw gemeente in cijfers: Huldenberg FOD Economie, AD Statistiek en Economische informatie FOD Economie, AD Statistiek en Economische informatie Uw gemeente in cijfers: Huldenberg Uw gemeente in cijfers: Huldenberg Inleiding Huldenberg : Huldenberg is een gemeente in de provincie Vlaams-Brabant en maakt deel uit van het Vlaams Gewest. Buurgemeentes zijn Bertem, Graven, Oud-Heverlee, Overijse, Tervuren en Waver. Huldenberg heeft een oppervlakte van 39,6 km2 en telt 9.464 ∗ inwoners, goed voor een bevolkingsdichtheid van 238,8 inwoners per km2. 61% ∗ van de bevolking van Huldenberg is tussen de 18 en 64 jaar oud. De gemeente staat op de 51ste plaats y van de 589 Belgische gemeentes in de lijst van het hoogste gemiddelde netto-inkomen per inwoner en op de 161ste plaats z in de lijst van de duurste bouwgronden. ∗. Situatie op 1/1/2011 y. Inkomstenjaar : 2009 - Aanslagjaar : 2010 z. Referentiejaar : 2011 FOD Economie, AD Statistiek en Economische informatie Uw gemeente in cijfers: Huldenberg Uw gemeente in cijfers: Huldenberg Inhoudstafel 1 Inhoudstafel 2 Bevolking Structuur van de bevolking Leeftijdspiramide voor Huldenberg 3 Grondgebied Bevolkingsdichtheid van Huldenberg en de buurgemeentes Bodembezetting 4 Vastgoed Prijs van bouwgrond in Belgi¨e Prijs van bouwgrond in Huldenberg en omgeving Prijs van bouwgrond : rangschikking 5 Inkomen Jaarlijks gemiddeld netto-inkomen per inwoner Jaarlijks gemiddeld netto-inkomen per inwoner voor Huldenberg en de buurgemeentes Evolutie van het jaarlijks gemiddeld netto-inkomen -

A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 B C D E F G H I J a B C D E F G H

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 POINTS D’INTÉRÊT ARRÊT BEZIENSWAARDIGHEDEN HALTE Asse Puurs via Liezele Humbeek Mechelen Drijpikkel Puurs via Willebroek Luchthaven Malines Malderen Mechelen - Antwerpen POINT OF INTEREST STOP Dendermonde Boom via Londerzeel Kapelle-op-den-Bos Zone tarifaire MTB Tariefzone MTB Antwerpen Malines - Anvers Boom via Tisselt Verbrande Brug Anvers Stade Roi Baudouin Heysel B2 Koning Boudewijn stadion Heizel Jordaen Pellenberg Heysel Ennepetal Minnemolen Sportcomplex Kerk Vilvoorde Heldenplein Atomium B3 Vilvoorde Station 64 Heizel Vlierkens 260 47 58 Kerk Machelen 820 Machelen A 250-251 460-461 A 230-231-232 Twee Leeuwenweg Vilvoorde Heysel Blokken Brussels Expo B3 Zone tarifaire MTB Tariefzone MTB Koningin Fabiola Heizel VTM Drie Fonteinen Parkstraat Aéroport Bruxelles National Windberg Kasteel Luchthaven Brussel-Nationaal Brussels Airport B8 Zellik Station Twyeninck Witloof Beaulieu Raedemaekers Brussels National Airport Dilbeek Keebergen Kaasmarkt Robbrechts Cortenbach Kampenhout RTBF 243-820 Kerk Kortenbach Haacht Diamant D6 Hoogveld VRT Kerk Haren-Sud SAO DGHR Domaine Militaire Omnisports Haren 270-271-470 Markt Bever De Villegas Buda Haren-Zuid Omnisport Haren Basilique de Koekelberg Rijkendal Militair Hospitaal DOO DGHR Militair Domein Dobbelenberg Bossaert-Basilique Gemeenteplein Biplan Basiliek van Koekelberg E2 Guido Gezelle Vijvers Hôpital Militaire 47 Bicoque Aérodrome Bossaert-Basiliek Tweedekker Vliegveld Leuven National Basilica 820 Van Zone tarifaire MTB Louvain 240 Bloemendal Long Bonnier Beyseghem 53 57 -

Grimbergen Prinsenstraat 3 - 1850 Grimbergen 02/260 12 11 [email protected]

Providentia cvba met sociaal oogmerk Burgerlijke vennootschap die de vorm van een handelsvennootschap heeft aangenomen bij de rechtbank van koophandel te Brussel, nr 97 Sociale huisvestingsmaatschappij door de VMSW erkend onder nr 222/8. Brusselsesteenweg 191 - 1730 Asse Bezoekdagen : maandag, woensdag en vrijdag van 8 tot 11.30 uur Contactgegevens gemeente Grimbergen Prinsenstraat 3 - 1850 Grimbergen 02/260 12 11 [email protected] www.grimbergen.be Medische spoedgevallen Politiezone Grimbergen OCMW Grimbergen 112 Vilvoordsesteenweg 191 Verbeytstraat 30 Brandweer 1850 Grimbergen 1800 Vilvoorde 112 02/272 72 72 02/267 15 05 Dringende politiehulp www.politie.be [email protected] 101 [email protected] Centrum Algemeen Welzijn JAC Inloop- ontmoetingscentrum (CAW) (jongerenwerking CAW) Komma Binnen (CAW) J.Baptiste Nowélei 33 J.Baptiste Nowélei 33 Mechelsesteenweg 55 1800 Vilvoorde 1800 Vilvoorde 1800 Vilvoorde 02/613 17 00 02/613 17 02 02/613 17 00 www.caw.be www.jac.be www.caw.be www.caw.be/chat www.jac.be/chat [email protected] [email protected] Bureau juridische bijstand Huurdersbond Huurdersbond VL-Brabant Gerechtsgebouw Vlaams-brabant - Leuven Adviespunt Vilvoorde Regenschapsstraat 63 - B1 Tiensevest 106 - B48 Lange Molenstraat 44 1000 Brussel 3000 Leuven 1800 Vilvoorde 02/519 84 94 - 02/511 50 45 016/25 05 14 016/25 05 14 - 0494/99 51 43 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.baliebrussel.be www.huurdersbond.be RVA-kantoor Vilvoorde VDAB Vilvoorde Burenbemiddeling -

Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT

Asse Beersel Dilbeek Drogenbos Grimbergen Hoeilaart Kraainem Linkebeek Machelen Meise Merchtem Overijse Sint-Genesius-Rode Sint-Pieters-Leeuw Tervuren Vilvoorde Wemmel Wezembeek-Oppem Zaventem Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering oktober 2011 Samenstelling Diensten voor het Algemeen Regeringsbeleid Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering Cijferboek: Naomi Plevoets Georneth Santos Tekst: Patrick De Klerck Met medewerking van het Documentatiecentrum Vlaamse Rand Verantwoordelijke uitgever Josée Lemaître Administrateur-generaal Boudewijnlaan 30 bus 23 1000 Brussel Depotnummer D/2011/3241/185 http://www.vlaanderen.be/svr INHOUD INLEIDING ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Algemene situering .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Demografie ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Aantal inwoners neemt toe ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Aantal huishoudens neemt toe....................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Bevolking is relatief jong én vergrijst verder