DUTTON.Thesis.July 16.FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lost Book of Enki.Pdf

L0ST BOOK °f6NK1 ZECHARIA SITCHIN author of The 12th Planet • . FICTION/MYTHOLOGY $24.00 TH6 LOST BOOK OF 6NK! Will the past become our future? Is humankind destined to repeat the events that occurred on another planet, far away from Earth? Zecharia Sitchin’s bestselling series, The Earth Chronicles, provided humanity’s side of the story—as recorded on ancient clay tablets and other Sumerian artifacts—concerning our origins at the hands of the Anunnaki, “those who from heaven to earth came.” In The Lost Book of Enki, we can view this saga from a dif- ferent perspective through this richly con- ceived autobiographical account of Lord Enki, an Anunnaki god, who tells the story of these extraterrestrials’ arrival on Earth from the 12th planet, Nibiru. The object of their colonization: gold to replenish the dying atmosphere of their home planet. Finding this precious metal results in the Anunnaki creation of homo sapiens—the human race—to mine this important resource. In his previous works, Sitchin com- piled the complete story of the Anunnaki ’s impact on human civilization in peacetime and in war from the frag- ments scattered throughout Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Hittite, Egyptian, Canaanite, and Hebrew sources- —the “myths” of all ancient peoples in the old world as well as the new. Missing from these accounts, however, was the perspective of the Anunnaki themselves What was life like on their own planet? What motives propelled them to settle on Earth—and what drove them from their new home? Convinced of the existence of a now lost book that formed the basis of THE lost book of ENKI MFMOHCS XND PKjOPHeCieS OF XN eXTfCXUfCWJTWXL COD 2.6CHXPJA SITCHIN Bear & Company Rochester, Vermont — Bear & Company One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.InnerTraditions.com Copyright © 2002 by Zecharia Sitchin All rights reserved. -

Mesopotamian Mythology

MESOPOTAMIAN MYTHOLOGY The myths, epics, hymns, lamentations, penitential psalms, incantations, wisdom literature, and handbooks dealing with rituals and omens of ancient Mesopotamian. The literature that has survived from Mesopotamian was written primarily on stone or clay tablets. The production and preservation of written documents were the responsibility of scribes who were associated with the temples and the palace. A sharp distinction cannot be made between religious and secular writings. The function of the temple as a food redistribution center meant that even seemingly secular shipping receipts had a religious aspect. In a similar manner, laws were perceived as given by the gods. Accounts of the victories of the kings often were associated with the favor of the gods and written in praise of the gods. The gods were also involved in the established and enforcement of treaties between political powers of the day. A large group of texts related to the interpretations of omens has survived. Because it was felt that the will of the gods could be known through the signs that the gods revealed, care was taken to collect ominous signs and the events which they preached. If the signs were carefully observed, negative future events could be prevented by the performance of appropriate apotropaic rituals. Among the more prominent of the Texts are the shumma izbu texts (“if a fetus…”) which observe the birth of malformed young of both animals and humans. Later a similar series of texts observed the physical characteristics of any person. There are also omen observations to guide the physician in the diagnosis and treatment of patients. -

Mesopotamian Culture

MESOPOTAMIAN CULTURE WORK DONE BY MANUEL D. N. 1ºA MESOPOTAMIAN GODS The Sumerians practiced a polytheistic religion , with anthropomorphic monotheistic and some gods representing forces or presences in the world , as he would later Greek civilization. In their beliefs state that the gods originally created humans so that they serve them servants , but when they were released too , because they thought they could become dominated by their large number . Many stories in Sumerian religion appear homologous to stories in other religions of the Middle East. For example , the biblical account of the creation of man , the culture of The Elamites , and the narrative of the flood and Noah's ark closely resembles the Assyrian stories. The Sumerian gods have distinctly similar representations in Akkadian , Canaanite religions and other cultures . Some of the stories and deities have their Greek parallels , such as the descent of Inanna to the underworld ( Irkalla ) resembles the story of Persephone. COSMOGONY Cosmogony Cosmology sumeria. The universe first appeared when Nammu , formless abyss was opened itself and in an act of self- procreation gave birth to An ( Anu ) ( sky god ) and Ki ( goddess of the Earth ), commonly referred to as Ninhursag . Binding of Anu (An) and Ki produced Enlil , Mr. Wind , who eventually became the leader of the gods. Then Enlil was banished from Dilmun (the home of the gods) because of the violation of Ninlil , of which he had a son , Sin ( moon god ) , also known as Nanna . No Ningal and gave birth to Inanna ( goddess of love and war ) and Utu or Shamash ( the sun god ) . -

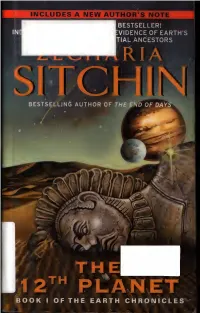

The Twelfth Planet

The Twelfth Planet The Earth Chronicles, #1 by Zecharia Sitchin, 1920-2010 Published: 1976 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Author‘s Note Prologue Genesis. & Chapter 1 … The Endless Beginning. Chapter 2 … The Sudden Civilization. Chapter 3 … Gods of Heaven and Earth. Chapter 4 … Sumer: Land of the Gods. Chapter 5 … The Nefilim: People of the Fiery Rockets. Chapter 6 … The Twelfth Planet. Chapter 7 … The Epic of Creation. Chapter 8 … Kingship of Heaven. Chapter 9 … Landing on Planet Earth. Chapter 10 … Cities of the Gods. Chapter 11 … Mutiny of the Anunnaki. Chapter 12 … The Creation of Man. Chapter 13 … The End of All Flesh. Chapter 14 … When the Gods Fled from Earth. Chapter 15 … Kingship on Earth. Sources About the Series Acknowledgements * * * * * Illustrations 1-1 Flintstones 1-2 Man has been preserved [attached] 1-3 Wearing some kind of goggles 2-4 Alphabets 2-5 Winged Globe 2-6 Layout of City 2-7 Cuneiform 2-8 Storage of Grains 2-9 Measuring rod and rolled string 2-10 Tablet of Temple [attached] 2-11 Ziggurat (Stairway to Heaven) 2-12 Cylinder Seal 2-13 Mathematical System 2-14 Surgical Thongs 2-15 Medical Radiation Treatment 2-16 Toga-style Clothing 2-17 Headdress 2-18 Head Jewelry 2-19 Horse Power 2-20 Harp Playing 2 Ancient Cities [attached] 3-21 Battle between Zeus and Typhon 3-22 Aphrodite 3-23 Jupiter 3-24 Taurus, Celestial Bull 3-25 Hittite Warriors 3-26 Hittite Warriors and Deities 3-27 Hittite Male and Female Deities 3-28 Meeting of Great Gods 3-29 Deities Meeting, Beit-Zehir 3-30 Eye Goggles of Gods 3-31 Goggles -

Sumerian Religion

1 אנשר אנשר (באכדית: Anshar או Anshur, מילולית:"ציר השמיים") הוא אל שמים מסופוטמי קדום. הוא מתואר כבן זוגה של אחותו קישאר. הזוג יחדיו מציינים את השמים (ההברה אן) והארץ (ההברה קי) במיתוס הבריאה אנומה אליש והם נמנים עם הדור השני לבריאה, ילדיהם של המפלצות לחמו (Lahmu) ולחאמו (Lahamu) ונכדיהם של תיאמת (Tiamat) ואפסו (Apsu), המסמנים את המים המלוחים והמתוקים בהתאמה. בתורם, הם בעצמם הוריו של אל שמים אחר בשם אנו (Anu). החל מימי סרגון השני, החלו האשורים לזהות את אנשר עם אשור בגירסתם למיתוס הבריאה, בגרסה זו בת זוגו היא נינ-ליל (NinLil). ערך זה הוא קצרמר בנושא מיתולוגיה. אתם מוזמנים לתרום לוויקיפדיה ו להרחיב אותו [1]. האל אנשר עומד על פר, נתגלה בחפירות העיר אשור הפניות editintro=%D7%AA%D7%91%D7%A0%D7%99%D7%AA%3A%D7%A7%D7%A6%D7%A8%D7%9E%D7%A8%2F%D7%94%D7%A8%D7%97%D7%91%D7%94&action=edit&http://he.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%D7%90%D7%A0%D7%A9%D7%A8 [1] המקורות והתורמים לערך 2 המקורות והתורמים לערך אנשר מקור: https://he.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?oldid=13750401 תורמים: GuySh, Ori, רועים המקורות, הרישיונות והתורמים לתמונה קובץ:Asur-Stier.PNG מקור: https://he.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=קובץ:Asur-Stier.PNG רישיון: Public Domain תורמים: Evil berry, Foroa, Gryffindor תמונה:Perseus-slays-medusa.jpg מקור: https://he.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=קובץ:Perseus-slays-medusa.jpg רישיון: GNU Free Documentation License תורמים: Bibi Saint-Pol, Editor at Large, Funfood, G.dallorto, Jastrow, Lokal Profil, Peter Andersen, Sreejithk2000 AWB, 4 עריכות אלמוניות רישיון Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 /creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0// Anu 1 Anu This article is about a myth. -

Tolkien, Bard of the Bible1

Tolkien, Bard of the Bible1 And in moments of exaltation we may call on all created things to join in our chorus, speaking on their behalf, as is done in Psalm 148, and in The Song of the Three Children in Daniel II. PRAISE THE LORD … all mountains and hills, all orchards and forests, all things that creep and birds on the wing. J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter to Camilla Unwin, Letters, p. 400. INTRODUCTION : TOLKIEN READER OF THE BIBLE The Bible stands as a particular influence on Tolkien's life and work. This conclusion has been well documented, even at the outset of Tolkien studies, and few scholars would now question the finely woven biblical tapestry of the Middle-earth corpus. Randel Helms pointed out, as early as 1981, in Tolkien and the Silmarils, the numerous parallels one could make between Tolkien's work and the biblical narratives.2 Christina Ganong Walton concluded, in her article 'Tolkien and the Bible', that 'Tolkien was familiar with the Bible in all its aspects because of his religious devotion and his work as a philologist'.3 Others have also indicated extra-Biblical influence, including Mesopotamian mythology, thus reinforcing the centrality of biblical patterns in Middle-earth.4 However, the reader must be careful not to be carried away by mere parallelisms, symbolism and 1 Unpublished paper. 2 Randel Helm, Tolkien and the Silmarils (London: Thames and Hudson, 1981); J. E. A. Tyler, The J. R. R. Tolkien's Companion (New York: Avon, 1977) 3 Christina Ganong Walton, “Tolkien and the Bible,' in Michael Drout (ed.), The J.R.R. -

BABYLONIAN CREATION from the Enuma Elish, 2050-1750 BC

BABYLONIAN CREATION From the Enuma Elish, 2050-1750 BC Before anything had a name, before there was firm ground or sky or the sun and moon there was Apsu, the sweet water sea and Tiamat, the salt water sea. When these two seas mingled, they created the gods Lahmu and Lahamu, who rose from the silt at the edge of the water. When Lahmu and Lahamu joined, they created the great gods Anshar, Kishar and Anu. From this generation of gods there arose mighty Ea and his many brothers. Ea and his brothers were restless - they surged over the waters day and night. Neither Apsu nor Tiamat could get any rest. They tried to plead with the gods to tread softly, but powerful Ea didn’t hear them. Apsu decided the only way to have some peace was to destroy Ea and his brothers. He began to plot their demise with some of the first generation gods. But Ea heard of their plans and struck him down first. This began a war among the gods. Tiamat was furious that her mate was killed, and she began producing great and ferocious monsters to slay Ea and his brothers. She created poisonous dragons and demons and serpents. She created the Viper, the Sphinx, the Lion, the Mad Dog and Scorpion Man. The chief of them all was called Kingu. He led the army of Tiamat’s monsters into heaven against Ea and his brothers to avenge Apsu’s death. While Tiamat fashioned her army, Ea and the goddess Damkina created the great god Marduk. -

Download Complete Volume

JOURNAL OF THE TllANSACTIONS OF THE VICTORIA INSTITUTE VOL. LXIV. JOURNAL OF THE TRANSACTIONS OF OR, VOL. LXIV. LONDON: lBublii!)ctr b!! tf)c institute, 1, <!i:cntrar JS11iitring-s;mcstmin1>trr, j,.00.1. A L L R I G H T S R E S E R V E D. 1932 LONDON: HAhfllSON AND SONS, LTD., PRINTERS IN ORDINARY TO HIS MAJESTY, ST. MARTIN'S LANE. PREFACE. -- THE present volume of Transactions-the sixty-fourth in series -makes its appearance at a time when the publications of Learned Societies are struggling with peculiar difficulties. The financial stringency dominating the commercial world has been reacting with serious consequences, also throughout the whole region of education and culture, religion and philanthropy; and to the sincere concern of its friends the Victoria Institute has not escaped the pressure of the times. The contents of the present volume will, we are sure, be held to reach the high standard maintained during many years past. Particular mention may be made of the Annual Address, delivered at the close of the session by Sir Ambrose Fleming, F.R.S., entitled "Some Recent Scientific Discoveries and Theories." The general body of papers, moreover, covers a wide range of subjects, Biblical and Theological, Scientific and Historical ; with Evolution theories treated under two aspects, and Assyriological research represented by studies that cannot but command the attention of Oriental scholars. With the list of Contents before him, the reader will not require a recital of the titles of the several essays now presented to the world. Suffice it to remark that, from first to last, when read at meetings of the Institute, the papers were accorded a hearty recep tion by Members and Associates, and the public generally. -

THE 12Th PLANET the STAIRWAY to HEAVEN the WARS of GODS and MEN the LOST REALMS WHEN TIME BEGAN the COSMIC CODE

INCLUDES A NEW AUTHOR'S P BESTSELLER! EVIDENCE OF EARTH’S TIAL ANCESTORS HARPER Now available in hardcover: U.S. $7.99 CAN. $8.99 THE LONG-AWAITED CONCLUSION TO ZECHARIA SITCHIN’s GROUNDBREAKING SERIES THE EARTH CHRONICLES ZECHARIA SITCHIN THE END DAYS Armageddon and Propfiffie.t of tlic Renirn . Available in paperback: THE EARTH CHRONICLES THE 12th PLANET THE STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN THE WARS OF GODS AND MEN THE LOST REALMS WHEN TIME BEGAN THE COSMIC CODE And the companion volumes: GENESIS REVISITED EAN DIVINE ENCOUNTERS . “ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT BOOKS ON EARTH’S ROOTS EVER WRITTEN.” East-West Magazine • How did the Nefilim— gold-seekers from a distant, alien planet— use cloning to create beings in their own image on Earth? •Why did these "gods" seek the destruc- tion of humankind through the Great Flood 13,000 years ago? •What happens when their planet returns to Earth's vicinity every thirty-six centuries? • Do Bible and Science conflict? •Are were alone? THE 12th PLANET "Heavyweight scholarship . For thousands of years priests, poets, and scientists have tried to explain how life began . Now a recognized scholar has come forth with a theory that is the most astonishing of all." United Press International SEP 2003 Avon Books by Zecharia Sitchin THE EARTH CHRONICLES Book I: The 12th Planet Book II: The Stairway to Heaven Book III: The Wars of Gods and Men Book IV: The Lost Realms Book V: When Time Began Book VI: The Cosmic Code Book VII: The End of Days Divine Encounters Genesis Revisited ATTENTION: ORGANIZATIONS AND CORPORATIONS Most Avon Books paperbacks are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchases for sales promotions, premiums, or fund-raising. -

Report to Donors 2019

Report to Donors 2019 Table of Contents Mission 2 Board of Trustees 3 Letter from the Director 4 Letter from the President 5 Exhibitions and Publications 6 Public, Educational, and Scholarly Programs 11 Family and School Programs 16 Museum and Research Services 17 Acquisitions 18 Statement of Financial Position 24 Donors 25 Mission he mission of the Morgan Library & Museum is to preserve, build, study, present, and interpret a collection T of extraordinary quality in order to stimulate enjoyment, excite the imagination, advance learning, and nurture creativity. A global institution focused on the European and American traditions, the Morgan houses one of the world’s foremost collections of manuscripts, rare books, music, drawings, and ancient and other works of art. These holdings, which represent the legacy of Pierpont Morgan and numerous later benefactors, comprise a unique and dynamic record of civilization as well as an incomparable repository of ideas and of the creative process. 2 the morgan library & museum Board of Trustees Lawrence R. Ricciardi Susanna Borghese ex officio President T. Kimball Brooker Colin B. Bailey Karen B. Cohen Barbara Dau Richard L. Menschel Flobelle Burden Davis life trustees Vice President Annette de la Renta William R. Acquavella Jerker M. Johansson Rodney B. Berens Clement C. Moore II Martha McGarry Miller Geoffrey K. Elliott Vice President John A. Morgan Marina Kellen French Patricia Morton Agnes Gund George L. K. Frelinghuysen Diane A. Nixon James R. Houghton Treasurer Gary W. Parr Lawrence Hughes Peter Pennoyer Herbert Kasper Thomas J. Reid Katharine J. Rayner Herbert L. Lucas Secretary Joshua W. Sommer Janine Luke Robert King Steel Charles F. -

SERVICE ELECTORAL ROLL- 2017(Draft W.R.T 01.01.2017) SL

S28-UTTARAKHAND 1 AC NO AND NAME- 2 - Yamunotri ( GEN ) LAST PART NO- 160 SERVICE ELECTORAL ROLL- 2017(Draft w.r.t 01.01.2017) SL. Name of RLN Father/Husband Date of Sex Service/Regim Rank Regiment Address House Address NO. Elector Type Name Birth (DOB) ent/Buckle No (Where individual (Permanent Address) (F/H Age Posted) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Tanuja H Hari Singh F Artillery Records Nasik Vill.- Murari 1 Road camp.Hyadrabad P.O.- Naugaon Teh.- Barkot 0 Pin.- 249132 Dist.- Uttarkashi Babita Rana H Vikram Singh F Garhwal Rifles Lansdowne Vill.- Bharkot 2 Rana C/O 56 APO P.O.- badhan gaon Teh.- Chinyalisaur 29 Pin.- 249196 Dist.- Uttarkashi Manjara H Nihal Singh F Central Industrial Security Vill.- Patara 3 Force Othpp Obra Distt. Sonebhadra (UP) P.O.- Patara Teh.- Dunda 0 Pin.- 249152 Dist.- Uttarkashi Pramila Devi H Vijendra Singh F Central Reserve Police Vill.- Pipalmandi 4 . force 91 Bn.C/O 56 APO P.O.- Chinyalisaur Teh.- Chinyalisaur 0 Pin.- 249132 Dist.- Uttarkashi Laxmi Devi H Rukam Singh F Dogra Regiement Vill.- Khand 5 Chauhan Faizabad (UP) P.O.- Khand Teh.- Chinyalisaur 0 Pin.- 249196 Dist.- Uttarkashi Sunita Devi H Vijendra Singh F Garhwal Rifles Lansdowne Vill.- Jagad Gaon 6 (UK) P.O.- Thati Dichli Teh.- Chinyalisaur 31 Pin.- 249196 Dist.- Uttarkashi Vijayswari H Mukund Lal F Garhwal Rifles Lansdowne Vill.- Pujiyar Gaon 7 Devi C/O 56 APO P.O.- Bangaon Teh.- Chinyalisaur 39 Pin.- 249152 Dist.- Uttarkashi Rakhi H Vijayanand F Garhwal Rifles Lansdowne Vill.- Manol maya Lodarka 8 (UK) P.O.- Junga Teh.- Dunda 31 Pin.- 249152 Dist.- Uttarkashi Rajni Devi H Bishan Singh F Garhwal Rifles Lansdowne Vill.- Garhwalgad 9 (UK) P.O.- Khalsi Teh.- Chinyalisaur 32 Pin.- 249196 Dist.- Uttarkashi ERO S28-UTTARAKHAND 2 AC NO AND NAME- 2 - Yamunotri ( GEN ) LAST PART NO- 160 SERVICE ELECTORAL ROLL- 2017(Draft w.r.t 01.01.2017) SL. -

Perceptions of the Serpent in the Ancient Near East: Its Bronze Age Role in Apotropaic Magic, Healing and Protection

PERCEPTIONS OF THE SERPENT IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST: ITS BRONZE AGE ROLE IN APOTROPAIC MAGIC, HEALING AND PROTECTION by WENDY REBECCA JENNIFER GOLDING submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN STUDIES at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR M LE ROUX November 2013 Snake I am The Beginning and the End, The Protector and the Healer, The Primordial Creator, Wisdom, all-knowing, Duality, Life, yet the terror in the darkness. I am Creation and Chaos, The water and the fire. I am all of this, I am Snake. I rise with the lotus From muddy concepts of Nun. I am the protector of kings And the fiery eye of Ra. I am the fiery one, The dark one, Leviathan Above and below, The all-encompassing ouroboros, I am Snake. (Wendy Golding 2012) ii SUMMARY In this dissertation I examine the role played by the ancient Near Eastern serpent in apotropaic and prophylactic magic. Within this realm the serpent appears in roles in healing and protection where magic is often employed. The possibility of positive and negative roles is investigated. The study is confined to the Bronze Age in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and Syria-Palestine. The serpents, serpent deities and deities with ophidian aspects and associations are described. By examining these serpents and deities and their roles it is possible to incorporate a comparative element into his study on an intra- and inter- regional basis. In order to accumulate information for this study I have utilised textual and pictorial evidence, as well as artefacts (such as jewellery, pottery and other amulets) bearing serpent motifs.