Pyritic Smelting at Deadwood: a Temporary Solution to Refractory Ores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mines An~ Mf 1Terals of Ulllasbf Ngton

I I I I I t I t I I t I I I I l I l I I t I I I I I I t • I I I I I I f Mines an~ Mf1terals of Ulllasbf ngton . • A~AL REPORT or GEORGE A. BETHUNE, FIRST STATE GEOLOGIST. OT.Y~rT'lA, \V A!':IT.: O. C. WOITE, tiTAT.E .PRINT.ER, 1801. I I t I I I t I I I I I I ' I f I I f I I I t I I t I f I I I I I t I I Tacoma, Wash.) Jan. ..............................1 891. To ······-·····-·················································-·····························.··········· I take pleasure in presenting this, the first annual report upon the Mines and Minerals of Washington. Yours very truly, GEO. A... BETHUNE, ~ First State Geologist. Mines anb Minerals of Ulllasbington . • ANNUAL REPORT OF GEORGE A . BETHUNE, FIRST STATE GEOL OGIST. OLYMPIA, WASU.: O. C. WU I TE, STATE PRI NTER. 1891. • ANNUAL REPORT. 'l'o his Excellency, Ct1ARU:S E. LAUG HTON, Governor·, and tlie lion orable, the membm·s of the Seri ate and House of Rep1·esentatives of the State of Washington: G~NTLEMEN- Herewitb find my annual report, as the first ~tate geologist of the State of Washington. In submitting this report for your consideration, and possibly for dissemination throughout the state, I beg leave first to call your attention to the following facts: By act of the legislature, the first to convene in this state, the office of which I have the honor to be the possessor, was created in March, 1890, and my appointment as state geologist and con firmation by the senate followed shortly thereafter. -

The Pharaohs' Gold: Ancient Egyptian Metallurgy

THE PHARAOHS' GOLD: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN METALLURGY TI n an age when mining is conducted on an lode country increased in size and scale, the clam industrial scale through the use of explosives, or for more efficient means of processing ores huge draglines, and enormous ore-carriers, there grew ever more strident and in response to this is a tendency to forget that mining was, and is, an demand milling processes grew increasingly activity involving the concerted efforts of human sophisticated. Greever notes that California's beings. In his depiction of mining activities in hardrock miners first relied on arrastras and California's nineteenth-century gold fields, Chilean mills to reduce their ores. When these William S. Greever in The Bonanza West: The Story devices failed to provide satisfactory returns of the Western Mining Frontier, 1848-1900 calls to California's argonauts then began to employ mind the human factor involved in the extraction stamp mills to process their gold ores.3 of ore from beneath the earth's surface: The processes underlying the operation of a stamp mill had changed little in the centuries [T)he deepest shafts in California leading up to the California gold rush.4 Greever quartz mining went down ... about compares the basic function of a stamp to that of a three hundred feet; often a deposit was pharmacist's mortar and pestle. In its simplest worked by a tunnel into a hillside or application, a stamp was dropped repeatedly on a even an open cut. The men used hand piece of metallic ore until the ore was reduced to drills, sledges, and a little black pow powder. -

A History of Tailings1

A HISTORY OF MINERAL CONCENTRATION: A HISTORY OF TAILINGS1 by Timothy c. Richmond2 Abstract: The extraction of mineral values from the earth for beneficial use has been a human activity- since long before recorded history. Methodologies were little changed until the late 19th century. The nearly simultaneous developments of a method to produce steel of a uniform carbon content and the means to generate electrical power gave man the ability to process huge volumes of ores of ever decreasing purity. The tailings or waste products of mineral processing were traditionally discharged into adjacent streams, lakes, the sea or in piles on dry land. Their confinement apparently began in the early 20th century as a means for possible future mineral recovery, for the recycling of water in arid regions and/or in response to growing concerns for water pollution control. Additional Key Words: Mineral Beneficiation " ... for since Nature usually creates metals in an impure state, mixed with earth, stones, and solidified juices, it is necessary to separate most of these impurities from the ores as far as can be, and therefore I will now describe the methods by which the ores are sorted, broken with hammers, burnt, crushed with stamps, ground into powder, sifted, washed ..•. " Agricola, 1550 Introduction identifying mining wastes. It is frequently used mistakenly The term "tailings" is to identify all mineral wastes often misapplied when including the piles of waste rock located at the mouth of 1Presented at the 1.991. National mine shafts and adi ts, over- American. Society for Surface burden materials removed in Mining and Reclamation Meeting surface mining, wastes from in Durango, co, May 1.4-17, 1.991 concentrating activities and sometimes the wastes from 2Timothy c. -

History of the Belshazzar and Mountain Chief Mines, Boise County, Idaho

History of the Belshazzar and Mountain Chief Mines, Boise County, Idaho Victoria E. Mitchell Idaho Geological Survey Morrill Hall, Third Floor Staff Report 08-3 University of Idaho July 2008 Moscow, Idaho 83844-3014 History of the Belshazzar and Mountain Chief Mines, Boise County, Idaho Victoria E. Mitchell Staff Reports present timely information for public distribution. This publication may not conform to the agency's standards. Idaho Geological Survey Morrill Hall, Third Floor Staff Report 08-3 University of Idaho July 2008 Moscow, Idaho 83844-3014 CONTENTS Introductory Note.. vii History of the Belshazzar and Mountain Chief Mines, Boise County, Idaho. 1 Introduction. 1 Geology. 1 Ore Characteristics.. 16 History of the Belshazzar and Mountain Chief Mines, Boise County, Idaho. 18 Belshazzar Mine.. 18 Mountain Chief Mine.. 25 References. 51 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Location of the Belshazzar and Mountain Chief mines, Boise County, Idaho.. 2 Figure 2. Boise Basin and area surrounding the Belshazzar and Mountain Chief mines. 3 Figure 3. Location of the Belshazzar and Mountain Chief Mines, Boise County, Idaho.. 4 Figure 4. Geology of the Belshazzar and Mountain Chief mines and vicinity, Boise County, Idaho.. 5 Figure 5. Sketch showing the underground features of the ore vein at the Belshazzar Mine.. 7 iii Figure 6. Sketch showing relationship of geologic features to the workings at the Mountain Chief Mine.. 8 Figure 7. Geologic map of the workings of the Belshazzar Mine in 1930. 10 Figure 8. Geologic map of the Quartzburg area, Boise Basin, Idaho.. 11 Figure 9. Geologic map of the workings of the Belshazzar Mine in 1932 or 1933. -

Mercury Use and Loss from Gold Mining in Nineteenth-Century Victoria 45

CSIRO Publishing The Royal Society of Victoria, 127, 44 –54, 2015 www.publish.csiro.au/journals/rs 10.1071/RS15017 Me RCuRy uSe and LOSS fROM GOLd MInInG In nIneTeenTh- CenTuRy Victoria Peter Davies1, susan Lawrence2 anD JoDi turnbuLL3 1, 2, 3 department of archaeology and history, La Trobe university, Bundoora, Victoria 3086 Correspondence: Peter davies, [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper reports on preliminary research into gold-mining-related mercury contamination in nineteenth-century Victoria. data drawn from contemporary sources, including Mineral Statistics of Victoria and Mining Surveyors Reports from 1868‒1888, are used to calculate quantities of mercury used by miners to amalgamate gold in stamp batteries and the rates of mercury lost in the process. Some of the mercury discharged from mining and ore milling flowed into nearby waterways and some remained in the waste residue, the tailings near the mills. We estimate that a minimum of 121 tons of mercury were discharged from stamp batteries in this period. although the figures fluctuate through time and space, they allow a good estimate of how much mercury was leaving the mine workings and entering Victorian creeks and rivers. Better understanding of historic mercury loss can provide the basis for improved mapping of mercury distribution in modern waterways, which can in turn inform the management of catchment systems. Keywords: mercury, gold mining, pollution, water, rivers In recent years, mercury in waterways has emerged as an et al. 1996) and new Zealand (Moreno et al. 2005), while important environmental issue in south-eastern australia extensive mercury pollution also resulted from silver and in many other areas. -

Anthropogenic Copper Inventories and Mercury Profiles from Lake Superior: Evidence for Mining Impacts

J. Great Lakes Res. 25(4):663–682 Internat. Assoc. Great Lakes Res., 1999 Anthropogenic Copper Inventories and Mercury Profiles from Lake Superior: Evidence for Mining Impacts W. Charles Kerfoot*,1, Sandra Harting1, Ronald Rossmann2, and John A. Robbins3 1Lake Superior Ecosystem Research Center and Department of Biological Sciences Michigan Technological University Houghton, Michigan 49931 2United States Environmental Protection Agency Mid-Continent Ecology Division, Large Lakes Research Station 9311 Groh Road Grosse Ile, Michigan 48138 3NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory 2205 Commonwealth Blvd Ann Arbor, Michigan 48105 ABSTRACT. During the past 150 years, the mining industry discharged more than a billion tons of tailings along Lake Superior shorelines and constructed numerous smelters in the watershed. Given the vast size of Lake Superior, were sediment profiles at locations far offshore impacted by nearshore activi- ties? Did copper and associated precious metal mining modify regional fluxes for copper and mercury? Samples from thirty sediment cores document that background concentrations of copper are high (mean 60.9 ± 7.0 µg/g), due to the proximity of natural ore sources. Anthropogenic inventories uncorrected for focusing also are high, ranging from 20 to 780 µg/cm2 (mean 187 ± 54 µg/cm2). Focusing factor correc- tions decrease the mean estimate and reduce variance (144 ± 24 µg/cm2). Several approaches to estimat- ing inputs suggest that only 6 to 10% of historic copper deposition originated directly from atmospheric sources, emphasizing terrestrial sources. Moreover, coastal sediment cores often show synchronous early increases in copper and mercury with buried maxima. Around the Keweenaw Peninsula, twenty-two cores trace high copper and mercury inventories back to mill and smelting sources. -

Tamarack Area Facilities Task 3

TAMARACK AREA FACILITIES TASK 3 - PHASE 2 REPORT Historical Archive Research and Mapping From Hubbell Beach through Tamarack City C&H Historic Properties of Torch Lake Prepared for: MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY Reclamation and Redevelopment Division 55195 US Highway 41 Calumet, Michigan 49913 Prepared by: MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY Carol MacLennan, Principal Investigator With John Baeten, Emma Schwaiger, Dan Schneider, Brendan Pelto Industrial Archaeology and Heritage Program Department of Social Sciences October 2014 Contract No. Y4110 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….5 Section 2: Narratives and Timelines ……………….……………...………………………………11 Ahmeek Mill Facilities1 - Narrative & Timeline ...……………...………………………………….12 Tamarack Reclamation Plant2 – Narrative & Timeline ………….……………………………..23 Lake Chemical Co. – Narrative & Timeline …………………………………………………………..46 Building Narratives ………………………………………………………………………………………..…55 Ahmeek Stamp Mill ………………………………………………..……………………………….58 Ahmeek Pump House ...……………………………………………………………………………60 Ahmeek Power House ……………………………………………………………………………..62 Ahmeek Transformer House ……………………………………………………………………64 Ahmeek Boiler House …...…………………………………………………………………………65 Tamarack Regrinding Plant ……………………………………………………………………..67 Tamarack Electric Sub-Station ...………………………………………………………………69 Tamarack Classifying Plant ..……………………………………………………………………70 Tamarack Flotation Plant ………………………………………………………………………..72 Tamarack Leaching Plant ...……………………………………………………………………...74 Tamarack Stamp -

Mining & Milling

Mining & Milling The Story of Park City 8TH GRADE SCIENCE CURRICULUM © Park City Historical Society & Museum All Rights Reserved These materials and the photographs are copyrighted by the Park City Historical Society & Museum. Permission is granted to make photocopies and transparencies of the handouts as directed in the lesson plans. Please contact the Park City Historical Society & Museum for permission to use materials for any other purpose. This program was developed by Johanna Fassbender, Curator of Education With special thanks to Richard Pick Keith J. Droste Thanks also to Courtney Cochley Josephine Janger David Hedderly-Smith James L. Hewitson Tom Barber Sydney Reed Park City Rotary Çlub Summit County Recreation, Arts and Parks Program The Underdog Foundation Dear Teachers, We hope that you will enjoy the 8th grade science curriculum and use it with your students to teach major physical and chemical con- cepts. Each lesson is keyed to the Utah Science Core Curriculum to help you deliver science instructions. Our curriculum includes history sections to provide the students with the appropriate background knowledge and get them excited about their hometown of Park City which was the unique setting for the science of mining and mineralo- gy. This goes along with our belief in an interdisciplinary approach which provides students with a more holistic knowledge and will empower them in future research projects. Almost all of the lesson plans allow for adjustments and provide you with different options, depending on the progress of your class. You can teach the entire curriculum within three weeks, or you can extend it to six weeks by slowing down the pace and reducing the workload. -

8402Ba D6745675513242bdb4

General principles of extraction of metals (i) Crushing and pulverization (ii) Concentration or dressing of the ore (iii) Calcination or roasting of the ore (iv) Reduction of metal oxides to free metal (v) Purification and refining of metal. Crushing and Pulverization The ore is generally obtained as big rock pieces. These big lumps of the ore are crushed to smaller pieces by using jaw-crushers and grinders. One of the plates of the crusher is stationary while the other moves to and fro and the crushed pieces are collected below The crushed pieces of the ore are then pulverized (powdered) in a stamp mill Concentration or Dressing of the Ore Generally, the ores are found mixed with earthy impurities like sand, clay, lime stone etc. These unwanted impurities in the ore are called gangue or matrix. The process of removal of gangue from powdered ore is called concentration or ore dressing. several methods for concentrating the ores. The choice of method depends on the nature of the ore. (i) Gravity separation (Hydraulic washing): concentration of heavier oxide ores, like haematite (Fe2O3) tinstone (SnO2) and gold (Au). (ii) Magnetic separation method: Those ores can be concentrated which either contain impurities which are magnetic or are themselves magnetic in nature. For example, the tin ore, tin stone (SnO2 ) itself is non-magnetic but contains magnetic impurities such as iron tungstate (FeWO4 ) and manganese tungstate (MnWO4 ) . (iii) Froth floatation method This method is especially applied to sulphide ores, such as galena (PbS), zinc blende (ZnS), or copper pyrites (CuFeS2 ). It is based on the different wetting properties of the surface of the ore and gangue particles. -

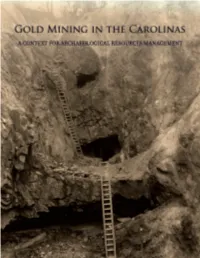

Gold Mining in the Carolinas

Gold Mining in the Carolinas A CONTEXT FOR ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT Report submitted to: Haile Gold Mine, Inc. • 7283 Haile Gold Mine Road • Kershaw, South Carolina 29067 Report prepared by: New South Associates • 6150 East Ponce de Leon Avenue • Stone Mountain, Georgia 30083 Natalie Adams Pope – Principal Investigator Brad Botwick – Archaeologist and Author March 31, 2012 • Final Report New South Associates Technical Report 2053 i Gold Mining in the Carolinas Abstract Gold mining was a significant early industry in North This context was written as a part of mitigation of and South Carolina. The first commercial gold mines Archaeological Site 38LA383, the Stamp Mill at Haile in the United States were in North Carolina, and the Gold Mine. The purpose of this context is to provide development of the mining industry led to important guidance for archaeological studies of gold mining developments in the region’s economy, settlement, in the Carolinas, regardless of whether it is related to industry, and landscape. Although a moderate number compliance with Federal laws, heritage studies, or of cultural resources relating to the Carolina gold academic research. This context can be used to aid mining industry have been identified, there has been researchers in making National Register evaluations little archaeological research into it to date. Most of under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation the research has been completed for compliance or Act but does not dictate mitigation efforts or actions, heritage projects, and site identification and evaluation which are negotiated on a case by case basis for eligible has been hindered by the lack of a comprehensive properties. -

%, ^SS^-S/ 0 R~Z CITY OR TOWN: STATER >' ^ /;O/ CODE V ^ ^ S — ,DATE

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Washington COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLAC ES Chelan INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sectiona> SEP 1 7 W4 mmm^iiiiiimmmimimm COMMON: > Blewett Arrastra AND/OR HISTORIC: till :::;:il!IB::!!!§l;!ll!ilt:Sl^ STREET AND NUMBER: ^T ^J^ f~ ~. *.~\ ,., .^ h U.S. Route 97 CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: #5 - Hon. Thomas S. Foley STATE 7 C°DE COUNTY: CODE Washington 53 litlllisiPJliiiiN;; • • •• - w- : -^;:^ ':"; ;-: ^ ^ ^- • ^ ; ' : •$$&&£% Chelan 007 STATUS ACCESS.BLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Q District Q Building 0 Public Public Acquisitic n: Q Occupied Yes: ss i—i 1 1 • j 1 1 Restricted G Site Q Structure D Private Q ' n Proc< s J£j Unoccupied 3 Object D Both D Beip 9 C onsidered r-j Preservation work 09 Unrestricted in progress '— ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) [~| Agricultural O Government [~| Park | | Transportation 1 1 Comments [~1 Commercial d Industrial [~] Private Residence f^i Other fSperfry) Q Educational 1 1 Mi itary | | Religious Roadside attraction I"! Entertainment CD Museum [~H Scientific iiillilllllllliiii^ OWNER'S NAME: STATE Washington State Department of Highways Washing STREET AND NUMBER: Highway Administration Building CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODF rt o Olympia Washincrton 53 ^xf-^xf^wm&xxv&f&zs^^ |iiii$i*ii$i:^F:::;iis*ii: -i^^^^^-'^miiMm-^^^^M WS^.W:^\m:[:mWf:W^f^^^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: COUNTY: District Engineer, Washington State Department of Hiahwavs n STREET AND NUMBER: D 1551 North Wenatchee Avenue D CITY OR TOWN: STATE CODE Wenatchee Washington 53 ^.•.-.-pi*8ii8i$i*WMi*p^ .-.-.•.-.• .•^.•w.;.-.»V'?-x ! '. -

The “Poor Man's Mill”: a Rich Vernacular Legacy

The “Poor Man’s Mill”: A Rich Vernacular Legacy Thad M. Van Bueren Arrastras are ancient ore milling devices that could be played a persistent but marginal role in the American cheaply built of local materials and operated with nearly any West, whereas they dominated the Mexican gold and sil- available source of power. Most were built and operated by ver mining industry. Those differences invite compar- small concerns in the American West. Those vernacular isons of the stamp milling and arrastra technologies as a devices offer rich clues about cultural traditions, the adapta- way to gain access to the cultural, economic, and scien- tion of technology, and the niches carved out by small opera- tific reasons behind technology choices. Although tors. In a broader comparative context, arrastras also provide stamp mills were favored by heavily capitalized Ameri- insights into choices of milling technologies. That interpretive can mining companies, arrastras were most often potential is illustrated with a small Italian mining operation employed by small operators relegated to the fringes of in California. the industry. Nevertheless, arrastras were used not only for prospecting but also for reprocessing stamp mill tail- ings and improving the recovery of gold in large indus- Introduction trial stamp mills. Their success in those latter roles has Arrastras are simple circular drag mills of ancient ori- intriguing implications for theories of economic ration- gin. They were popular throughout the Mediter- ality and the evolution of global capitalism. ranean region since Phoenician times and were intro- duced in the New World by the Spanish, following Both themes are explored as a way to situate the inter- discoveries of plentiful gold and silver in Mexico and pretation of arrastras in the American West.