Some Issues Surrounding the Reduction of Macroeconomics to Microeconomics Author(S): Alan Nelson Source: Philosophy of Science, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine

with Open Texts Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine VERSION 2017 – REVISION B ADAPTABLE | ACCESSIBLE | AFFORDABLE Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-SA) advancing learning Champions of Access to Knowledge OPEN TEXT ONLINE ASSESSMENT All digital forms of access to our high- We have been developing superior on- quality open texts are entirely FREE! All line formative assessment for more than content is reviewed for excellence and is 15 years. Our questions are continuously wholly adaptable; custom editions are pro- adapted with the content and reviewed for duced by Lyryx for those adopting Lyryx as- quality and sound pedagogy. To enhance sessment. Access to the original source files learning, students receive immediate per- is also open to anyone! sonalized feedback. Student grade reports and performance statistics are also provided. SUPPORT INSTRUCTOR SUPPLEMENTS Access to our in-house support team is avail- Additional instructor resources are also able 7 days/week to provide prompt resolu- freely accessible. Product dependent, these tion to both student and instructor inquiries. supplements include: full sets of adaptable In addition, we work one-on-one with in- slides and lecture notes, solutions manuals, structors to provide a comprehensive sys- and multiple choice question banks with an tem, customized for their course. This can exam building tool. include adapting the text, managing multi- ple sections, and more! Contact Lyryx Today! [email protected] advancing learning Principles of Microeconomics an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine Version 2017 — Revision B BE A CHAMPION OF OER! Contribute suggestions for improvements, new content, or errata: A new topic A new example An interesting new question Any other suggestions to improve the material Contact Lyryx at [email protected] with your ideas. -

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — Preface to Game Theory

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — prefacetogametheory (Mar 11, 2012) School of Economics The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya Oligopoly is a market in which only a few firms compete with one another, • and entry of new firmsisimpeded. The situation is known as the Cournot model after Antoine Augustin • Cournot, a French economist, philosopher and mathematician (1801-1877). In the basic example, a single good is produced by two firms (the industry • is a “duopoly”). Cournot’s oligopoly model (1838) — A single good is produced by two firms (the industry is a “duopoly”). — The cost for firm =1 2 for producing units of the good is given by (“unit cost” is constant equal to 0). — If the firms’ total output is = 1 + 2 then the market price is = − if and zero otherwise (linear inverse demand function). We ≥ also assume that . The inverse demand function P A P=A-Q A Q To find the Nash equilibria of the Cournot’s game, we can use the proce- dures based on the firms’ best response functions. But first we need the firms payoffs(profits): 1 = 1 11 − =( )1 11 − − =( 1 2)1 11 − − − =( 1 2 1)1 − − − and similarly, 2 =( 1 2 2)2 − − − Firm 1’s profit as a function of its output (given firm 2’s output) Profit 1 q'2 q2 q2 A c q A c q' Output 1 1 2 1 2 2 2 To find firm 1’s best response to any given output 2 of firm 2, we need to study firm 1’s profit as a function of its output 1 for given values of 2. -

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics Global Citizenship Program ECON 3020 Intermediate Microeconomics (3) Knowledge Areas (....) This course covers advanced theory and applications in microeconomics. Topics include utility theory, consumer and ARTS Arts Appreciation firm choice, optimization, goods and services markets, resource GLBL Global Understanding markets, strategic behavior, and market equilibrium. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. PNW Physical & Natural World ECON 3030 Intermediate Macroeconomics (3) QL Quantitative Literacy This course covers advanced theory and applications in ROC Roots of Cultures macroeconomics. Topics include growth, determination of income, employment and output, aggregate demand and supply, the SSHB Social Systems & Human business cycle, monetary and fiscal policies, and international Behavior macroeconomic modeling. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. Global Citizenship Program ECON 3100 Issues in Economics (3) Skill Areas (....) Analyzes current economic issues in terms of historical CRI Critical Thinking background, present status, and possible solutions. May be repeated for credit if content differs. Prerequisite: ECON 2000. ETH Ethical Reasoning INTC Intercultural Competence ECON 3150 Digital Economy (3) Course Descriptions The digital economy has generated the creation of a large range OCOM Oral Communication of significant dedicated businesses. But, it has also forced WCOM Written Communication traditional businesses to revise their own approach and their own value chains. The pervasiveness can be observable in ** Course fulfills two skill areas commerce, marketing, distribution and sales, but also in supply logistics, energy management, finance and human resources. This class introduces the main actors, the ecosystem in which they operate, the new rules of this game, the impacts on existing ECON 2000 Survey of Economics (3) structures and the required expertise in those areas. -

FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021

9/15/21 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021 Course # Class # Units Course Title Day Time Location Instruction Mode Instructor Limit 1078-001 20457 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 8:00-8:50 ECON 117 IN PERSON Bentz 47 1078-002 20200 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 6:30-7:20 ECON 119 IN PERSON Hurt 47 1078-004 13409 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Marein 71 1088-001 18745 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 6:30-7:20 HLMS 141 IN PERSON Zhou, S 47 1088-002 20748 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 8:00-8:50 HLMS 211 IN PERSON Flynn 47 2010-100 19679 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Keller 500 2010-200 14353 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Carballo 500 2010-300 14354 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Bottan 500 2010-600 14355 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Klein 200 2010-700 19138 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Gruber 200 2020-100 14356 4 Principles of Macroeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Valkovci 400 3070-010 13420 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 9:10-10:00 ECON 119 IN PERSON Barham 47 3070-020 21070 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 2:20-3:35 ECON 117 IN PERSON Chen 47 3070-030 20758 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 11:10-12:25 ECON 119 IN PERSON Choi 47 3070-040 21443 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 1:50-2:40 ECON 119 IN PERSON Bottan 47 3080-001 22180 3 Intermediate Macroeconomic Theory MWF 11:30-12:20 -

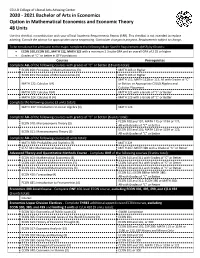

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

Principles of Microeconomics

PRINCIPLES OF MICROECONOMICS A. Competition The basic motivation to produce in a market economy is the expectation of income, which will generate profits. • The returns to the efforts of a business - the difference between its total revenues and its total costs - are profits. Thus, questions of revenues and costs are key in an analysis of the profit motive. • Other motivations include nonprofit incentives such as social status, the need to feel important, the desire for recognition, and the retaining of one's job. Economists' calculations of profits are different from those used by businesses in their accounting systems. Economic profit = total revenue - total economic cost • Total economic cost includes the value of all inputs used in production. • Normal profit is an economic cost since it occurs when economic profit is zero. It represents the opportunity cost of labor and capital contributed to the production process by the producer. • Accounting profits are computed only on the basis of explicit costs, including labor and capital. Since they do not take "normal profits" into consideration, they overstate true profits. Economic profits reward entrepreneurship. They are a payment to discovering new and better methods of production, taking above-average risks, and producing something that society desires. The ability of each firm to generate profits is limited by the structure of the industry in which the firm is engaged. The firms in a competitive market are price takers. • None has any market power - the ability to control the market price of the product it sells. • A firm's individual supply curve is a very small - and inconsequential - part of market supply. -

COURSE OUTLINE ECON 100 Introduction to Microeconomics 3.0 CREDITS

APPLIED SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT School of Business and Leadership Fall, 2017 COURSE OUTLINE ECON 100 Introduction to Microeconomics 3.0 CREDITS PREPARED BY: Jennifer Moorlag DATE: August 31, 2017 APPROVED BY: DATE: APPROVED BY ACADEMIC COUNCIL: (date) RENEWED BY ACADEMIC COUNCIL: (date) ECON 100 Course Outline by Jennifer Moorlag is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License 2 APPLIED SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT Economics 100 3 Credits Fall, 2017 Introduction to Microeconomics INSTRUCTOR: Jennifer Moorlag, B.A, M.Ed. OFFICE HOURS: M/W 10am-noon F 9am-noon OFFICE LOCATION: A2412 CLASSROOM: A2402 E-MAIL: [email protected] TIME: M/W 8:30am-10:00am TELEPHONE: 867.668.8756 DATES: Sept 6 – Dec 21 COURSE DESCRIPTION This course discusses the terminology, concepts, theory, methodology and limitations of current microeconomic analysis. The course provides students with a theoretical structure to analyze and understand economics as it relates to individuals and businesses. In addition, it seeks to provide students with an understanding of how political, social and market forces determine and affect the Canadian economy. This introductory course explores the principles of production and consumption – and the exchange of goods and services – in a market economy. In particular, it compliments courses in the Business Administration program by highlighting the various market mechanisms that influence managerial decision-making. PREREQUISITES None EQUIVALENCY OR TRANSFERABILITY SFU ECON 103 (3) -

The Ghosts of Hayek in Orthodox Microeconomics: Markets As Information Processors 2019

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Edward Nik-Khah; Philip Mirowski The Ghosts of Hayek in Orthodox Microeconomics: Markets as Information Processors 2019 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12241 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Nik-Khah, Edward; Mirowski, Philip: The Ghosts of Hayek in Orthodox Microeconomics: Markets as Information Processors. In: Armin Beverungen, Philip Mirowski, Edward Nik-Khah u.a. (Hg.): Markets. Lüneburg: meson press 2019, S. 31–70. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12241. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell 4.0 Lizenz zur Verfügung Attribution - Non Commercial 4.0 License. For more information gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 [ 2 ] The Ghosts of Hayek in Orthodox Microeconomics: Markets as Information Processors Edward Nik- Khah and Philip Mirowski In media studies, there is recurrent fascination with how commu- nication, especially when couched in terms of “information,” tends to influence many spheres of social life and intellectual endeavor. Some of the key figures in that discipline have been especially at- tentive to the implications for politics of the modern advent of the “information economy.” Nevertheless, we think that there has been little impetus among media scholars to explore how other disci- plines, and in this case orthodox economics, have been providing competing accounts of the nature and importance of information over the same rough time frame. Furthermore, we think they might be surprised to learn that Friedrich Hayek and the neoliberals have been important in framing inquiry into the information economy for the larger culture for a couple of generations. -

Publics and Markets. What's Wrong with Neoliberalism?

12 Publics and Markets. What’s Wrong with Neoliberalism? Clive Barnett THEORIZING NEOLIBERALISM AS A egoists, despite much evidence that they POLITICAL PROJECT don’t. Critics of neoliberalism tend to assume that increasingly people do act like this, but Neoliberalism has become a key object of they think that they ought not to. For critics, analysis in human geography in the last this is what’s wrong with neoliberalism. And decade. Although the words ‘neoliberal’ and it is precisely this evaluation that suggests ‘neoliberalism’ have been around for a long that there is something wrong with how while, it is only since the end of the 1990s neoliberalism is theorized in critical human that they have taken on the aura of grand geography. theoretical terms. Neoliberalism emerges as In critical human geography, neoliberal- an object of conceptual and empirical reflec- ism refers in the first instance to a family tion in the process of restoring to view a of ideas associated with the revival of sense of political agency to processes previ- economic liberalism in the mid-twentieth ously dubbed globalization (Hay, 2002). century. This is taken to include the school of This chapter examines the way in which Austrian economics associated with Ludwig neoliberalism is conceptualized in human von Mises, Friedrich von Hayek and Joseph geography. It argues that, in theorizing Schumpeter, characterized by a strong com- neoliberalism as ‘a political project’, critical mitment to methodological individualism, an human geographers have ended up repro- antipathy towards centralized state planning, ducing the same problem that they ascribe commitment to principles of private property, to the ideas they take to be driving forces and a distinctive anti-rationalist epistemo- behind contemporary transformations: they logy; and the so-called Chicago School of reduce the social to a residual effect of more economists, also associated with Hayek but fundamental political-economic rationalities. -

AS Economics: Microeconomics Ability to Pay Where Taxes Should

AS Economics: Microeconomics Key Term Glossary Ability to pay Where taxes should be set according to how well a person can afford to pay Ad valorem tax An indirect tax based on a percentage of the sales price of a good or service Adam Smith One of the founding fathers of modern economics. His most famous work was the Wealth of Nations (1776) - a study of the progress of nations where people act according to their own self-interest - which improves the public good. Smith's discussion of the advantages of division of labour remains a potent idea Adverse selection Where the expected value of a transaction is known more accurately by the buyer or the seller due to an asymmetry of information; e.g. health insurance Air passenger duty APD is a charge on air travel from UK airports. The level of APD depends on the country to which an airline passenger is flying. Alcohol duties Excise duties on alcohol are a form of indirect tax and are chargeable on beer, wine and spirits according to their volume and/or alcoholic content Alienation A sociological term to describe the estrangement many workers feel from their work, which may reduce their motivation and productivity. It is sometimes argued that alienation is a result of the division of labour because workers are not involved with the satisfaction of producing a finished product, and do not feel part of a team. Allocative efficiency Allocative efficiency occurs when the value that consumers place on a good or service (reflected in the price they are willing and able to pay) equals the cost of the resources used up in production (technical definition: price eQuals marginal cost). -

Microeconomics Definitions Microeconomics Is the Study of Individuals, Firms Or Markets

Microeconomics Definitions microeconomics is the study of individuals, firms or markets. Macroeconomics is the study of a whole country's economy growth an increase in production or income over a period of time development an improvement in the quality of life for the majority of the population sustainable development development that doesn't leave future generations worse off positive something that can be objectively measured normative something that is subjective and has a value judgement ceteris paribus everything else remains equal (latin) land any raw material labour people paid to work capital something man-made used in production entrepreneur a person that combines the other resources in production rent the payment from land wage the payment for labour interest the payment from capital profit the payment to entrepreneurs utility a unit of happiness opportunity cost the difference between the best and next best alternatives free good one with no opportunity cost economic good one with an opportunity cost mixed economy one that combines the private and public sector public sector that owned by the government private sector that owned by private individuals planned economy one where what, how and for whom to produce is decided by the government market economy one where the free market decides what and how to produce transition economy one changing from planned to market economy market a place where buyers and sellers meet monopoly a market of one firm or dominated by one firm oligopoly a market dominated by a few firms monopolistic