Cardiac Lesions Associated with Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prolonged Asystole During Hypobaric Chamber Training

Olgu Sunumları Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 520 Case Reports 2012; 12: 517-24 contraction/ventricular tachycardia’s originating from mitral annulus contractions arising from the mitral annulus: a case with a pure annular are rarely reported (1). origin. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2009; 32: 680-2. [CrossRef] PVCs arising from the mitral annulus frequently originate from 5. Kimber SK, Downar E, Harris L, Langer G, Mickleborough LL, Masse S, et al. anterolateral, posteroseptal and posterior sites (2). It has been reported Mechanisms of spontaneous shift of surface electrocardiographic configuration that 2/3 of the PVCs arising from the mitral annulus originate from during ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 15: 1397-404. [CrossRef] anterolateral site (2). Furthermore, small part of these arrhythmias origi- Address for Correspondence/Yaz›şma Adresi: Dr. Ömer Uz nates from the anteroseptal site of the mitral annulus. Ablation of this Gülhane Askeri Tıp Akademisi Haydarpasa, Kardiyoloji Kliniği, İstanbul-Türkiye site may be technically very challenging. Cases have been reported that Phone: +90 216 542 34 65 Fax: +90 216 348 78 80 successful catheter ablation of the premature ventricular contraction E-mail: [email protected] origin from the anteroseptal site of the mitral annulus can be performed Available Online Date/Çevrimiçi Yayın Tarihi: 22.06.2012 either by a transseptal or transaortic approach in literature (3, 4). ©Telif Hakk› 2012 AVES Yay›nc›l›k Ltd. Şti. - Makale metnine www.anakarder.com web Anterolateral site of the mitral annulus is in close proximity to anterior sayfas›ndan ulaş›labilir. of the right ventricle outflow tract, left ventricular epicardium near to ©Copyright 2012 by AVES Yay›nc›l›k Ltd. -

Ventricular Rhythms Originate Below the Branching Portion of The

Northwest Community Healthcare Paramedic Program VENTRICULAR DYSRHYTHMIAS Pacemakers Connie J. Mattera, M.S., R.N., EMT-P Reading assignments: Bledsoe Vol 3; pp. 96-109 SOPs: VT with pulse; Ventricular fibrillation/PVT; Asystole/PEA Drugs: Amiodarone, magnesium, epinephrine 1mg/10mL Procedure manual: Defibrillation; Mechanical Circulatory Support (MCS) using a Ventricular Assist Device KNOWLEDGE OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of the reading assignments, class and homework questions, reviewing the SOPs, and working with their small group, each participant will independently do the following with at least an 80% degree of accuracy and no critical errors: 1. Identify the intrinsic rates, morphology, conduction pathways, and common ECG features of ventricular beats/rhythms. 2. Identify on a 6-second strip the following: a) Idioventricular rhythm b) Accelerated idioventricular rhythm c) Ventricular tachycardia: monomorphic & polymorphic d) Ventricular escape beats e) Premature Ventricular Contractions (PVCs) f) Ventricular fibrillation g) Asystole h) Paced rhythms i) Intraventricular conduction defects (Bundle branch blocks) 3. Systematically evaluate each complex/rhythm for the following: a) Rate (atrial and ventricular) b) Rhythm: Regular/irregular - R-R Interval, P-P Interval c) Presence/absence/morphology of P waves d) Presence/absence/morphology of QRS complexes d) P-QRS relationships f) QRS duration 4. Correlate the cardiac rhythm with patient assessment findings to determine the emergency treatment for each rhythm according to NWC EMSS SOPs. 5. Discuss the action, prehospital indications, side effects, dose and contraindications of the following during VT a) Amiodarone b) Magnesium 6. Describe the indications, equipment needed, critical steps, and patient monitoring parameters for cardioversion and defibrillation. 7. Identify the management of a patient with an implanted defibrillator and/or pacemaker. -

The Unsuspected Complications of Bacterial Endocarditis Imaged by Gallium-67 Scanning

The Unsuspected Complications of Bacterial Endocarditis Imaged by Gallium-67 Scanning Shobha P. Desai and David L. Yuille Nuclear Medicine Department, St. Luke's Medical Center, Milwaukee, @V&sconsin tivity in the region of the aortic valve which extended into the In this case report, we present a patient with bacterial endocar right atrium (Fig. 1)but was better appreciated on an axial SPECF ditiswho was evaluatedby 67(@imagingfor persistentfever image (Fig. 2). despitetreatmentwith multipleintravenousantibiotics.Afthough cardiac catheterizationconfirmeda densely calcified bicuspid evidence of bactenal endocarditiswas absent wfth @“Gaimag aorticvalve with both stenosis and insufficiencyas well as what ing,the studydemonstratedfindingsthat representcomplica was thoughtto be aveiy largerightsinus ofvalsalva aneurysm.At tions of bacterial endocarditis. The procedure demonstrated surgery, there was evidence of epicarditisand pericarditisand a moderatepencardialuptakeof isotopeandthus pro@4dedthe hugerightsinus of valsalva abscess was foundwhich was eroding first evidence of pehcardi@swhich was later confirmed at sur into the aortic wall. The aortic valve annuluswas debrided, the gery.The studyalsodemonstratedmi@ increasedactivityin abscess cavity was drainedandthe patient's diseased aorticvalve thevicinityoftheaorticrootandnghtattium.A sinusofvalsalva was replacedwith a no. 25 St. Jude's prosthesis (St. JudeMedical abscess, complicatingthe underlyingdiagnosis of bacterialen Inc., St. Paul, MN). The immediatepostoperativeperiodwas docarc@bs,was -

Cardiac Arrhythmias in Survivors of Sudden Cardiac Death Requiring Impella Assist Device Therapy

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Cardiac Arrhythmias in Survivors of Sudden Cardiac Death Requiring Impella Assist Device Therapy Khaled Q. A. Abdullah 1,2, Jana V. Roedler 1, Juergen vom Dahl 1, Istvan Szendey 1, Dimitrios Dimitroulis 1, Lars Eckardt 3, Albert Topf 4, Bernhard Ohnewein 4, Lorenz Fritsch 4, Fabian Föttinger 4, Mathias C. Brandt 4, Bernhard Wernly 4,5,6 , Lukas J. Motloch 4 and Robert Larbig 2,3,* 1 Department of Cardiology, Hospital Maria Hilf Moenchengladbach, 41063 Moenchengladbach, Germany; [email protected] (K.Q.A.A.); [email protected] (J.V.R.); [email protected] (J.v.D.); [email protected] (I.S.); [email protected] (D.D.) 2 Department of Cardiology, University Hospital Aachen, RWTH University Aachen, 52062 Aachen, Germany 3 Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Division of Electrophysiology, University of Muenster, 48149 Muenster, Germany; [email protected] 4 Department of Cardiology, Clinic II for Internal Medicine, University Hospital Salzburg, Paracelsus Medical University, 5020 Salzburg, Austria; [email protected] (A.T.); [email protected] (B.O.); [email protected] (L.F.); [email protected] (F.F.); [email protected] (M.C.B.); [email protected] (B.W.); [email protected] (L.J.M.) 5 Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Medicine and Intensive Care Medicine, Paracelsus Medical University of Salzburg, 5026 Salzburg, Austria 6 Center for Public Health and Healthcare Research, Paracelsus Medical University of Salzburg, 5026 Salzburg, Austria Citation: Abdullah, K.Q.A.; Roedler, * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-216-1892-4770 J.V.; vom Dahl, J.; Szendey, I.; Dimitroulis, D.; Eckardt, L.; Topf, A.; Abstract: In this retrospective single-center trial, we analyze 109 consecutive patients (female: 27.5%, Ohnewein, B.; Fritsch, L.; Föttinger, F.; median age: 69 years, median left ventricular ejection fraction: 20%) who survived sudden cardiac et al. -

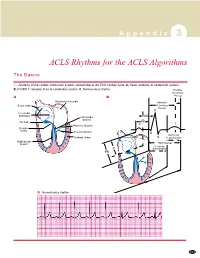

ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms

A p p e n d i x 3 ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms The Basics 1. Anatomy of the cardiac conduction system: relationship to the ECG cardiac cycle. A, Heart: anatomy of conduction system. B, P-QRS-T complex: lines to conduction system. C, Normal sinus rhythm. Relative Refractory A B Period Bachmann’s bundle Absolute Sinus node Refractory Period R Internodal pathways Left bundle AVN branch AV node PR T Posterior division P Bundle of His Anterior division Q Ventricular Purkinje fibers S Repolarization Right bundle branch QT Interval Ventricular P Depolarization PR C Normal sinus rhythm 253 A p p e n d i x 3 The Cardiac Arrest Rhythms 2. Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia Pathophysiology ■ Ventricles consist of areas of normal myocardium alternating with areas of ischemic, injured, or infarcted myocardium, leading to chaotic pattern of ventricular depolarization Defining Criteria per ECG ■ Rate/QRS complex: unable to determine; no recognizable P, QRS, or T waves ■ Rhythm: indeterminate; pattern of sharp up (peak) and down (trough) deflections ■ Amplitude: measured from peak-to-trough; often used subjectively to describe VF as fine (peak-to- trough 2 to <5 mm), medium-moderate (5 to <10 mm), coarse (10 to <15 mm), very coarse (>15 mm) Clinical Manifestations ■ Pulse disappears with onset of VF ■ Collapse, unconsciousness ■ Agonal breaths ➔ apnea in <5 min ■ Onset of reversible death Common Etiologies ■ Acute coronary syndromes leading to ischemic areas of myocardium ■ Stable-to-unstable VT, untreated ■ PVCs with -

Severe Hypotension, Bradycardia and Asystole After Sugammadex Administration in an Elderly Patient

medicina Case Report Severe Hypotension, Bradycardia and Asystole after Sugammadex Administration in an Elderly Patient Carmen Fierro 1 , Alessandro Medoro 1 , Donatella Mignogna 1 , Carola Porcile 1 , Silvia Ciampi 1 , Emanuele Foderà 1 , Romeo Flocco 2, Claudio Russo 1,3,* and Gennaro Martucci 2 1 Department of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Molise, 86100 Campobasso, Italy; c.fi[email protected] (C.F.); [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (E.F.) 2 Anesthesia and Intensive Care Unit, “A. Cardarelli” Hospital, Azienda Sanitaria Regionale del Molise, 86100 Campobasso, Italy; romeofl[email protected] (R.F.); [email protected] (G.M.) 3 UOC Governance del Farmaco, Azienda Sanitaria Regionale del Molise, 86100 Campobasso, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Background and Objectives: Sugammadex is a modified γ-cyclodextrin largely used to prevent postoperative residual neuromuscular blockade induced by neuromuscular aminosteroid blocking agents. Although Sugammadex is considered more efficacious and safer than other drugs, such as Neostigmine, significant and serious complications after its administration, such as hypersen- sitivity, anaphylaxis and, more recently, severe cardiac events, are reported. Case presentation: In this report, we describe the case of an 80-year-old male with no medical history of cardiovascular disease who was scheduled for percutaneous nephrolithotripsy under general anesthesia. The intraoperative course was uneventful; however, the patient developed a rapid and severe hypotension, asystole and cardiac arrest after Sugammadex administration. Spontaneous cardiac activity and hemodynamic Citation: Fierro, C.; Medoro, A.; stability was restored with pharmacological therapy and chest compression. -

Fire Fighter FACE Report No. F2005-16, Captain Suffers an Acute Aortic Dissection After Responding to Two Alarms and Subsequentl

F2005 16 A Summary of a NIOSH fi re fi ghter fatality in ves ti ga tion August 24, 2005 Captain Suffers an Acute Aortic Dissection After Responding to Two Alarms and Subsequently Dies Due to Hemopericardium – Pennsylvania SUMMARY On January 21, 2004, a 35-year-old male vol- signifi cant risk to the safety and health of unteer Captain responded to two alarms: a mo- themselves or others. tor vehicle crash (MVC) with an injury, and a reported house fi re that turned out to be a false • Perform an annual physical performance alarm. Returning to the fi re station after the false (physical ability) evaluation to ensure alarm, he complained of not feeling well and went fi re fi ghters are physically capable of home. After being home about 15 minutes, he performing the essential job tasks of collapsed. The Captain was transported to the lo- structural fi re fi ghting. cal hospital and later fl own to a regional hospital for diagnostic testing. Despite having a cardiac • Phase in a mandatory wellness/fi tness pro- catheterization with coronary angiography, and a gram for fi re fi ghters to reduce risk factors chest computed tomography (CT) scan, his aortic for cardiovascular disease and improve dissection went undiagnosed. He was treated for cardiovascular capacity. bilateral pneumonia but his condition continued to deteriorate. Despite cardiopulmonary resus- • Ensure that fi re fi ghters are cleared for citation (CPR) and advanced life support (ALS), duty by a physician knowledgeable about the Captain was pronounced dead approximately the physical demands of fi re fi ghting, the 20 hours after his initial complaint. -

Adult Cardiac Protocols TABLE of CONTENTS Asystole/Pulseless

Oakland County Adult Cardiac Protocols Date: February 1, 2013 Page 1 of 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Asystole/Pulseless Electrical Activity__________________________ Section 2-1 Bradycardia ______________________________________________ Section 2-2 Cardiac Arrest - General____________________________________ Section 2-3 Cardiac Arrest – Return of Spontaneous Circulation (ROSC)_______ Section 2-4 Chest Pain/Acute Coronary Syndrome_________________________ Section 2-5 Hypothermia Cardiac Arrest ____________________ Section 2-6 Pulmonary Edema/CHF (Addendum)______________________ Section 2-7 Tachycardia __________________________________ Section 2-8 Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia Section 2-9 MCA Name: Oakland County Section 2 MCA Board Approval Date: February 1, 2013 MDCH Approval Date: May 31, 2013 MCA Implementation Date: August 1, 2013 Michigan Adult Cardiac Protocols ASYSTOLE / PULSELESS ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY (PEA) Date: May 31, 2012 Page 1 of 1 Asystole / Pulseless Electrical Activity During CPR, consider reversible causes of Asystole/PEA and treat as indicated. Causes and efforts to correct them include but are not limited to: Hypovolemia – give NS IV/IO fluid bolus up to 1 liter, wide open. Hypoxia – reassess airway and ventilate with high flow oxygen Tension pneumothorax – see Pleural Decompression Procedure Hypothermia – follow Hypothermia Cardiac Arrest Protocol rapid transport Hyperkalemia (history of renal failure) – see #5 below. Pre-Medical Control PARAMEDIC 1. Follow the Cardiac Arrest - General Protocol. 2. Confirm that patient is in asystole by evaluating more than one lead. 3. Administer Epinephrine 1:10,000, 1 mg (10 ml) IV/IO, repeat every 3-5 minutes. 4. Per MCA selection, administer Vasopressin 40 Units IV/IO in place of second dose of Epinephrine. Vasopressin 40 Units IV/IO Included ✔ Not Included 5. -

CARDIAC ARREST: PULSELESS ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY (PEA) and ASYSTOLE

CARDIAC ARREST: PULSELESS ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY (PEA) and ASYSTOLE APPROVED: Gregory Gilbert, MD EMS Medical Director Sam Barnett EMS Administrator DATE: January 2012 Information Needed: • See Cardiac Arrest overview protocol Objective Findings: • Pulseless (check carotid and femoral pulses) • Apneic • Electrical activity on the monitor exclusive of ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia Treatment: • Assess patient and confirm pulselessness • Start CPR and assure adequacy of compressions and ventilations. An emphasis on high quality CPR with minimal interruptions in chest compressions. • Determine cardiac rhythm • BLS should use Automatic External Defibrillator if available and shock as appropriate • For Asystole or PEA, confirm in two ECG leads • Establish large bore IV or IO of normal saline • Give epinephrine (1:10,000) 1 mg IV/IO, repeat q 3 to 5 minutes until rhythm change or termination of resuscitation efforts • Assess for possible causes of PEA and administer corresponding treatments (See Precautions and Comments) • Consider advanced airway. Confirm ventilation with capnography • Fluid challenge 250-1000 cc NS for suspected hypovolemia • In the setting of renal failure, dialysis, DKA, or potassium ingestion (possible hyperkalemia), give calcium chloride 1 gm IV/IO over one minute then flush and then administer sodium bicarbonate 1 mEq/kg IV/IO Precautions and Comments: • Consider termination of efforts if patient is unresponsive to initial treatments (see Guideline for Determining Death in the Field Policy) • External -

Management of Asymptomatic Arrhythmias

Europace (2019) 0, 1–32 EHRA POSITION PAPER doi:10.1093/europace/euz046 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/europace/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/europace/euz046/5382236 by PPD Development LP user on 25 April 2019 Management of asymptomatic arrhythmias: a European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus document, endorsed by the Heart Failure Association (HFA), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA), and Latin America Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS) David O. Arnar (Iceland, Chair)1*, Georges H. Mairesse (Belgium, Co-Chair)2, Giuseppe Boriani (Italy)3, Hugh Calkins (USA, HRS representative)4, Ashley Chin (South Africa, CASSA representative)5, Andrew Coats (United Kingdom, HFA representative)6, Jean-Claude Deharo (France)7, Jesper Hastrup Svendsen (Denmark)8,9, Hein Heidbu¨chel (Belgium)10, Rodrigo Isa (Chile, LAHRS representative)11, Jonathan M. Kalman (Australia, APHRS representative)12,13, Deirdre A. Lane (United Kingdom)14,15, Ruan Louw (South Africa, CASSA representative)16, Gregory Y. H. Lip (United Kingdom, Denmark)14,15, Philippe Maury (France)17, Tatjana Potpara (Serbia)18, Frederic Sacher (France)19, Prashanthan Sanders (Australia, APHRS representative)20, Niraj Varma (USA, HRS representative)21, and Laurent Fauchier (France)22 ESC Scientific Document Group: Kristina Haugaa23,24, Peter Schwartz25, Andrea Sarkozy26, Sanjay Sharma27, Erik Kongsga˚rd28, Anneli Svensson29, Radoslaw Lenarczyk30, Maurizio Volterrani31, Mintu Turakhia32, -

Case Report of the Patient with Acute Myocardial Infarction: "From Flatline to Stent Implantation"

ACTA FACULTATIS MEDICAE NAISSENSIS DOI: 10.1515/afmnai-2017-0036 UDC: 616.127-005.8 616.12-008.46:616.12-008.315 036.88-083.98 Case report Case Report of the Patient with Acute Myocardial Infarction: "From Flatline to Stent Implantation" Dejan Petrović1,2, Marina Deljanin Ilić1,2, Bojan Ilić1, Sanja Stojanović1, Milovan Stojanović1, Dejan Simonović1 1University of Niš, Faculty of Medicine, Niš, Serbia 2Institute for Treatment and Rehabilitation , “Niška Banja”, Niška Banja, Serbia SUMMARY Asystole is a rare primary manifestation in the development of sudden cardiac death (SCD), and survival during cardiac arrest as the consequence of asystole is extremely low. The aim of our paper is to illustrate successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and rare and severe form of cardiac arrest - asystole. A very short time between cardiac arrest in acute myocardial infarction, which was manifested by asystole, and the adequate CPR measures that have been taken are of great importance for the survival of our patient. After successful reanimation, the diagnosis of anterior wall AMI with ST segment elevation was established. The right therapeutic strategy is certainly the early primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI). In less than two hours, after recording the "flatline" and successful reanimation, the patient was in the catheterization laboratory, where a successful PPCI of LAD was performed, after emergency coronary angiography. In the further treatment course of the patient, the majority of risk factors were corrected, except for smoking, which may be the reason for newly discovered lung tumor disease. Early recognition and properly applied treatment of CPR can produce higher rates of survival. -

AC 1. Adult Asystole / Pulseless Electrical Activity

Adult Asystole / Pulseless Electrical Activity History Signs and Symptoms Differential SAMPLE Pulseless See Reversible Causes below Estimated downtime Apneic See Reversible Causes below No electrical activity on ECG DNR, MOST, or Living Will No heart tones on auscultation Cardiac Arrest Protocol AC 3 Decomposition Rigor mortis Dependent lividity Blunt force trauma Criteria for Death / No Resuscitation Injury incompatible with Review DNR / MOST Form life YES Extended downtime with asystole NO Utilize this protocol with Do not begin Team Focused CPR Procedure resuscitation Resuscitation Follow AED Procedure Protocol I Deceased Subjects if available Policy Consider reversible causes Consider Chest Decompression Procedure in ROSC at any time setting of possible chest trauma Reversible Causes Go to P Protocol Adult Section Cardiac Post Resuscitation Cardiac Monitor; place Zoll Stat Padz and Hypovolemia Protocol secondary set of pads Hypoxia IV / IO Procedure Hydrogen ion (acidosis) Hypothermia Epinephrine 0.1mg/mL (1:10,000) 1 mg IV / IO Hypo / Hyperkalemia Every 5 minutes A Tension pneumothorax Normal Saline Bolus 500 mL IV / IO Tamponade; cardiac May repeat as needed Toxins Maximum 2 L Thrombosis; pulmonary (PE) Thrombosis; coronary (MI) Airway protocols as indicated Consider Early for PEA 1. Repeated NS boluses for Airway protocols possible hypovolemia as indicated 2. Glucagon 4 mg IV/IO/IM for suspected beta blocker or calcium channel blocker overdose 3. Calcium chloride 1 g IV/IO for After four (4) cycles of CPR after initial ALS P suspected hyperkalemia/ in place consider LUCAS3 placement hypocalcemia 4. Sodium bicarbonate 50 mEq IV/IO for possible overdose, hyperkalemia, renal failure 5. Consider dopamine drip 6.