Adopted from Pdflib Image Sample

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Puzzles About Descriptive Names Edward Kanterian

Puzzles about descriptive names Edward Kanterian To cite this version: Edward Kanterian. Puzzles about descriptive names. Linguistics and Philosophy, Springer Verlag, 2010, 32 (4), pp.409-428. 10.1007/s10988-010-9066-1. hal-00566732 HAL Id: hal-00566732 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00566732 Submitted on 17 Feb 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Linguist and Philos (2009) 32:409–428 DOI 10.1007/s10988-010-9066-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Puzzles about descriptive names Edward Kanterian Published online: 17 February 2010 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 Abstract This article explores Gareth Evans’s idea that there are such things as descriptive names, i.e. referring expressions introduced by a definite description which have, unlike ordinary names, a descriptive content. Several ignored semantic and modal aspects of this idea are spelled out, including a hitherto little explored notion of rigidity, super-rigidity. The claim that descriptive names are (rigidified) descriptions, or abbreviations thereof, is rejected. It is then shown that Evans’s theory leads to certain puzzles concerning the referential status of descriptive names and the evaluation of identity statements containing them. -

CV, Paul Horwich, March 2017

Curriculum Vitae Paul Horwich Department of Philosophy 212 998 8320 (tel) New York University 212 995 4178 (fax) 5 Washington Place [email protected] New York, NY 10003 EDUCATION Cornell University (Philosophy) Ph.D. 1975 Cornell University (Philosophy) M.A. 1973 Yale University (Physics and Philosophy) M.A. 1969 Oxford University (Physics) B.A. 1968 TITLE OF DOCTORAL THESIS: The Metric and Topology of Time. EMPLOYMENT Spring 2007 Visiting Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Tokyo Fall 2006 Visiting Professor of Philosophy, Ecole Normale Superieure, Paris 2005–present Professor, Department of Philosophy, New York University 2000–2005 Kornblith Distinguished Professor, Philosophy Program, Graduate Center of the City University of New York Spring 1998 Visiting Professor of Philosophy, University of Sydney 1994–2000 Professor, Department of Philosophy, University College London Fall 1994 Associate Research Director, Institute d'Histoire et Philosophie des Sciences et Technique, CNRS, Paris 1987–1994 Professor, Department of Linguistics And Philosophy, Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1980–1987 Associate Professor of Philosophy, MIT Fall 1978 Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy, University of California at Los Angeles 1973–1980 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, MIT CV, Paul Horwich, March 2017 GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2008–9 Guggenheim Fellowship Spring 2007 Fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science 2007 U.S. National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship Fall 1988 U.S. National Science Foundation -

The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): Mathematician, Logician, and Philosopher

Louis deRosset { Spring 2019 Russell: The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): mathematician, logician, and philosopher. He's one of the founders of analytic philosophy. \On Denoting" is a founding document of analytic philosophy. It is a paradigm of philosophical analysis. An analysis of a concept/phenomenon c: a recipe for eliminating c-vocabulary from our theories which still captures all of the facts the c-vocabulary targets. FOR EXAMPLE: \The Name View Analysis of Identity." 2. Russell's target: Denoting Phrases By a \denoting phrase" I mean a phrase such as any one of the following: a man, some man, any man, every man, all men, the present King of England, the present King of France, the centre of mass of the Solar System at the first instant of the twentieth century, the revolution of the earth round the sun, the revolution of the sun round the earth. (479) Includes: • universals: \all F 's" (\each"/\every") • existentials: \some F " (\at least one") • indefinite descriptions: \an F " • definite descriptions: \the F " Later additions: • negative existentials: \no F 's" (480) • Genitives: \my F " (\your"/\their"/\Joe's"/etc.) (484) • Empty Proper Names: \Apollo", \Hamlet", etc. (491) Russell proposes to analyze denoting phrases. 3. Why Analyze Denoting Phrases? Russell's Project: The distinction between acquaintance and knowledge about is the distinction between the things we have presentation of, and the things we only reach by means of denoting phrases. [. ] In perception we have acquaintance with the objects of perception, and in thought we have acquaintance with objects of a more abstract logical character; but we do not necessarily have acquaintance with the objects denoted by phrases composed of words with whose meanings we are ac- quainted. -

Russell's Theory of Descriptions

Russell’s theory of descriptions PHIL 83104 September 5, 2011 1. Denoting phrases and names ...........................................................................................1 2. Russell’s theory of denoting phrases ................................................................................3 2.1. Propositions and propositional functions 2.2. Indefinite descriptions 2.3. Definite descriptions 3. The three puzzles of ‘On denoting’ ..................................................................................7 3.1. The substitution of identicals 3.2. The law of the excluded middle 3.3. The problem of negative existentials 4. Objections to Russell’s theory .......................................................................................11 4.1. Incomplete definite descriptions 4.2. Referential uses of definite descriptions 4.3. Other uses of ‘the’: generics 4.4. The contrast between descriptions and names [The main reading I gave you was Russell’s 1919 paper, “Descriptions,” which is in some ways clearer than his classic exposition of the theory of descriptions, which was in his 1905 paper “On Denoting.” The latter is one of the optional readings on the web site, and I reference it below sometimes as well.] 1. DENOTING PHRASES AND NAMES Russell defines the class of denoting phrases as follows: “By ‘denoting phrase’ I mean a phrase such as any one of the following: a man, some man, any man, every man, all men, the present king of England, the centre of mass of the Solar System at the first instant of the twentieth century, the revolution of the earth around the sun, the revolution of the sun around the earth. Thus a phrase is denoting solely in virtue of its form.” (‘On Denoting’, 479) Russell’s aim in this article is to explain how expressions like this work — what they contribute to the meanings of sentences containing them. -

Adopted from Pdflib Image Sample

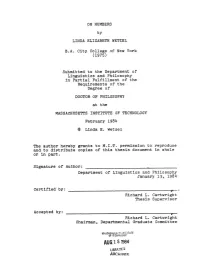

ON NUMBERS by LINDA ELIZABETH WETZEL B.A. City College of New York (1975) Submitted to the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 1984 @ Linda E. Wetzel The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute copies of this thesis document in whole or in part, Signature of Author: Department of Linguistics and Philosophy January 13, 1984 Certified by : .-_ - Richard L, Cartwright Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: v Richard L. Cartwright Chairman, Departmental Graduate Committee ON NUMBERS Linda E, Wetzel Submitted to the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy of October 21, 1983 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ABSTRACT We talk as though there are numbers. The view I defend, the "popularn view, has it that there -are numbers. However, since they clearly are not physical objects, we reason that they must be abstract ones. This suggests a realm of non-spatial non-temporal objects standing in numerical relations; arithmetic knowledge is then knowledge of this realm. But how do spatio~temporal creatures like ourselves come to have knowledge of this realm? The problem ("Benacerrafls probleni") can be avoided by arguing that there are no numbers. In "What Numbers Could Not Bew Benacerraf himself took such a route. In chapter one, I discuss three of Benacerrafls arguments, showing that the first is circular, that the second involves a consideration that can be explained by less drastic means than supposing there are no numbers, and that the third would, if successful, show that neither sets nor expressions exist either. -

Intrinsic Explanation and Field's Dispensabilist Strategy Sydney-Tilburg Conference on Reduction and the Special Sciences Russ

Intrinsic Explanation and Field’s Dispensabilist Strategy Sydney-Tilburg Conference on Reduction and the Special Sciences Russell Marcus Department of Philosophy, Hamilton College 198 College Hill Road Clinton NY 13323 [email protected] (315) 859-4056 (office) (315) 381-3125 (home) September 2007 ~2880 words Abstract: Philosophy of mathematics for the last half-century has been dominated in one way or another by Quine’s indispensability argument. The argument alleges that our best scientific theory quantifies over, and thus commits us to, mathematical objects. In this paper, I present new considerations which undermine the most serious challenge to Quine’s argument, Hartry Field’s reformulation of Newtonian Gravitational Theory. Intrinsic Explanation, Page 1 §1: Introduction Quine argued that we are committed to the existence mathematical objects because of their indispensable uses in scientific theory. In this paper, I defend Quine’s argument against the most popular objection to it, that we can reformulate science without reference to mathematical objects. I interpret Quine’s argument as follows:1 (QIA) QIA.1: We should believe the theory which best accounts for our empirical experience. QIA.2: If we believe a theory, we must believe in its ontic commitments. QIA.3: The ontic commitments of any theory are the objects over which that theory first-order quantifies. QIA.4: The theory which best accounts for our empirical experience quantifies over mathematical objects. QIA.C: We should believe that mathematical objects exist. An instrumentalist may deny either QIA.1 or QIA.2, or both. Regarding QIA.1, there is some debate over whether we should believe our best theories. -

Robert C. Koons

ROBERT C. KOONS ADDRESSES Department of Philosophy 1, University Station C3500 University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 78712-3500 (512) 471-5530 [email protected] EDUCATION 1979 B.A., Philosophy, Michigan State University, Summa cum laude 1981 B.A., Philosophy and Theology, Oxford University First Class Honours 1987 Ph.D., Philosophy, UCLA AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Metaphysics and Epistemology Philosophical Logic Philosophy of Religion PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Sept. 1, 2000 Professor, University of Texas at Austin 1993-2000 Associate Professor, University of Texas at Austin 1987-1993 Assistant Professor, University of Texas at Austin HONORS Visiting Scholar, Nanjing University, April/May 2007 Philosopher-in-Residence, Valparaiso University, Spring 2001 Gustave O. Arlt Award (Council of Graduate Schools) 1992 Carnap Prize (UCLA) 1987 Richard M. Weaver Fellow, 1985-87 Danforth Fellow, l979-85 Dillistone Scholar (Oriel College, Oxford), l980 Marshall Scholar, l979-1981 ROBERT C. KOONS PAGE 2 RESEARCH GRANTS National Science Foundation, Division of Information, Robotics and Intelligent Systems, "The Logic and Representation of Properties and Propositions for Computer Natural Language Processing," with Kamp, Bonevac, Asher, and C. Smith, 1988-1989. National Research Council Travel Grant for Attendance of the Ninth International Congress on Logic, Methodology and Philosophy of Science, Uppsala, Sweden, 1991. Faculty Research Assignment, "The Logic of Causation and Teleological Function," Spring 1997. Visiting Scholar, Institute for Advanced -

Russell's Theory of Descriptions

Russell’s theory of descriptions September 23, 2004 1 Propositions and propositional functions . 1 2 Descriptions and names . 3 2.1 Indefinite descriptions do not stand for particular objects in the same waynamesdo ............................... 3 2.2 Three puzzles caused by the assimilation of definite descriptions to names . 4 2.2.1 The problem of negative existentials . 4 2.2.2 Substitution failures . 5 2.2.3 The law of the excluded middle . 5 2.3 The distinction between primary and secondary occurrence . 5 3 Russell’s theory of descriptions . 6 3.1 Indefinite descriptions . 6 3.2 Definite descriptions . 6 3.3 ‘Everyone’, ‘someone’ . 7 3.4 Strengths of Russell’s theory . 7 4 Objections to Russell’s theory . 7 4.1 Incomplete definite descriptions . 7 4.2 Other uses of ‘the’: generics . 7 4.3 The view that sentences containing descriptions say something about propositional functions . 8 5 Russell’s view of names . 8 6 The metaphysical importance of Russell’s theory . 8 1 Propositions and propositional functions Russell (unlike contemporary theorists) means by ‘proposition’, as he puts it, “pri- marily a form of words which expresses what is either true or false.” Roughly, then, ‘propositions’ in Russell refers to ‘declarative sentences.’ Propositional functions are something else: “A ‘propositional function,’ in fact, is an expression containing one or more undetermined constituents, such that, when values are assigned to 1 these constituents, the expression becomes a proposition. Examples of propositional functions are easy to give: “x is human” is a propositional function; so long as x remains undetermined, it is neither true nor false, but when a value is assigned to x it becomes a true or false proposition.” (An Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy, pp. -

Realism and Anti-Realism in Mathematics

REALISM AND ANTI-REALISM IN MATHEMATICS The purpose of this essay is (a) to survey and critically assess the various meta- physical views - Le., the various versions of realism and anti-realism - that people have held (or that one might hold) about mathematics; and (b) to argue for a particular view of the metaphysics of mathematics. Section 1 will provide a survey of the various versions of realism and anti-realism. In section 2, I will critically assess the various views, coming to the conclusion that there is exactly one version of realism that survives all objections (namely, a view that I have elsewhere called full-blooded platonism, or for short, FBP) and that there is ex- actly one version of anti-realism that survives all objections (namely, jictionalism). The arguments of section 2 will also motivate the thesis that we do not have any good reason for favoring either of these views (Le., fictionalism or FBP) over the other and, hence, that we do not have any good reason for believing or disbe- lieving in abstract (i.e., non-spatiotemporal) mathematical objects; I will call this the weak epistemic conclusion. Finally, in section 3, I will argue for two further claims, namely, (i) that we could never have any good reason for favoring either fictionalism or FBP over the other and, hence, could never have any good reason for believing or disbelieving in abstract mathematical objects; and (ii) that there is no fact of the matter as to whether fictionalism or FBP is correct and, more generally, no fact of the matter as to whether there exist any such things as ab- stract objects; I will call these two theses the strong epistemic conclusion and the metaphysical conclusion, respectively. -

Logical Atomism in Russell and Wittgenstein

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 04/15/11, SPi c h a p t e r 1 0 logical atomism in russell and wittgenstein i a n p r o o p s I n t r o d u c t i o n Russell and Wittgenstein develop diff erent, though closely related, versions of a posi- tion that has come to be known as ‘logical atomism’. Wittgenstein’s version is presented in the Tractatus , and discussed in the various pre-Tractatus manuscripts. Russell’s is pre- sented most fully in a set of eight lectures given in Gordon Square, London in early 1918. Th ese lectures, which are familiar to us today under the title ‘Th e Philosophy of Logical Atomism’ (Russell 1918/1956 : 175–281 , hereaft er ‘PLA’), were originally serialized in the Monist during the years 1918 and 1919. In them Russell attempts to synthesize his own ideas with those of Wittgenstein’s 1913 Notes on Logic . Although PLA is oft en treated as the defi nitive presentation of Russell’s logical atomism, we should not forget that Russell had already arrived at many elements of this doctrine before he encountered Wittgenstein. Th is earlier, pure Russellian, brand of logical atomism is fi rst set out in Russell’s 1911 article ‘Analytical Realism’ 1 —a text in which the phrase ‘logical atomism’ appears for the fi rst time. (See Monk 1996 , 200 .) It is further developed in certain chap- ters of the Problems of Philosophy of 1912. 2 Analytical realism, Russell explains, is a form of atomism because it maintains—in contrast to the British Hegelianism of Bradley, McTaggart, Joachim, and others,3 fi rst, 1 Th is work was composed in the summer of 1911, and so before Russell’s fi rst encounter with Wittgenstein. -

SCOTT SOAMES USC School of Philosophy 3709 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, CA 90089-0451 [email protected] / (213) 740-0798 October 2020

SCOTT SOAMES USC School of Philosophy 3709 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, CA 90089-0451 [email protected] / (213) 740-0798 October 2020 EDUCATION Stanford University, BA., 1968 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ph.D. Philosophy, 1976 ACADEMIC HONORS Phi Beta Kappa, 1967 Danforth Graduate Fellow, 1971-76 Woodrow Wilson Graduate Fellow, 1971 AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS American Academy of Arts and Sciences, elected in 2010. Albert S. Raubenheimer Award for excellence in research, teaching, and service, 2009. The Raubenheimer is the highest faculty honor of the College of Letters, Arts, and Sciences of the University of Southern California. Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences Fellowship 1998-99 Academic Year. John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship 1989- 90. Title of Project: "Truth and Meaning" Class of 1936 Bicentennial Preceptorship, Princeton University, 1982-1985 National Endowment for the Humanities Research Fellowship for 1978-79. Title of Project: "The Philosophical Investigation of Linguistic Theory" ACADEMIC POSITIONS Director of the School of Philosophy, University of Southern California, August 2007 – Distinguished Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Southern California, 2011 – Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Southern California, 2004 - 2010 Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, July 1989 - 2004 Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, July 1985 - June 1989 2 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, September 1980 - June 1985 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Yale University, January 1976 - June 1980 Instructor, Linguistics Department, M.I.T., 1974-75 VISITING POSITIONS Franklin Pease Garcia Visiting Professor, Department of Humanities, Catholic Pontifical University of Peru, Lima Peru, May 18 – June 25, 2015. Visiting Professor, Department of Philosophy, Graduate School & University Center, City University of New York, Spring 1997. -

Jared Warren

JARED WARREN Curriculum Vitae B [email protected] T 904.866.8439 www.jaredwarren.org Education 2015 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PhD in Philosophy COMMITTEE: David Chalmers, Hartry Field (chair), Crispin Wright Areas of Specialization Mind and Language, Metaphysics and Epistemology, Mathematics and Logic Areas of Competence History of Analytic Philosophy, Metaethics, Philosophy of Science Publications (1) “The Possibility of Truth by Convention”(2015) The Philosophical Quarterly 65(258): 84-93. (2) “Quantifier Variance and the Collapse Argument” (2015) The Philosophical Quarterly 65(259): 241-253. (3) “Conventionalism, Consistency, and Consistency Sentences” (2015) Synthese 192(5): 1351-1371. (4) “Talking with Tonkers” (2015) Philosophers’ Imprint 15(24): 1-24. (5) “Trapping the Metasemantic Metaphilosophical Deflationist?” (2016) Metaphilosophy 47(1): 108-121. (6) “Sider on the Epistemology of Structure” (2016) Philosophical Studies 173(9): 2417-2435. (7) “Epistemology vs Non-Causal Realism” (2017) Synthese 194(5): 1643-1662. (8) “Revisiting Quine on Truth by Convention” (2017) The Journal of Philosophical Logic 46(2): 119-139. 1 (9) “Internal and External Questions Revisited” (2016) The Journal of Philosophy 113(4): 177-209. (10) “Change of Logic, Change of Meaning” (forthcoming) Philosophy & Phenomenological Research. (11) “Quantifier Variance and Indefinite Extensibility” (2017) The Philosophical Review 126(1): 81-122. (12) “A Metasemantic Challenge for Mathematical Determinacy” (forthcoming) Synthese. (with Daniel Waxman) (13) “Quantifier Variance