Child Work Or Child Labour? the Caddie Question in Edwardian Golf1 Wray Vamplew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golf Glossary by John Gunby

Golf Glossary by John Gunby GENERAL GOLF TERMS: Golf: A game. Golf Course: A place to play a game of golf. Golfer,player: Look in the mirror. Caddie: A person who assists the player with additional responsibilities such as yardage information, cleaning the clubs, carrying the bag, tending the pin, etc. These young men & women have respect for themselves, the players and the game of golf. They provide a service that dates back to 1500’s and is integral to golf. Esteem: What you think of yourself. If you are a golfer, think very highly of yourself. Humor: A state of mind in which there is no awareness of self. Failure: By your definition Success: By your definition Greens fee: The charge (fee) to play a golf course (the greens)-not “green fees”. Always too much, but always worth it. Greenskeeper: The person or persons responsible for maintaining the golf course Starting time (tee time): A reservation for play. Arrive at least 20 minutes before your tee time. The tee time you get is the time when you’re supposed to be hitting your first shot off the first tee. Golf Course Ambassador (Ranger): A person who rides around the golf course and has the responsibility to make sure everyone has fun and keep the pace of play appropriate. Scorecard: This is the form you fill out to count up your shots. Even if you don’t want to keep score, the cards usually have some good information about each hole (Length, diagrams, etc.). And don’t forget those little pencils. -

BERNHARD LANGER Sunday, April 21, 2013

Greater Gwinnett Championship INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT: BERNHARD LANGER Sunday, April 21, 2013 DAVE SENKO: Bernhard, congratulations, win number 18 and just a continuation of what's been a great year so far with two wins, two 2nds and a 3rd. Maybe just share your thoughts on winning by three shots, especially after to getting off to a little bit of a slow start on Friday. BERNHARD LANGER: It certainly was a slow start, I think I shot 9-under in the pro-am on Thursday and then shot 1-over the next day. I wasn't pleased with that. When I first set foot here at Sugarloaf, I really enjoyed the golf course. I said this is an amazing, good golf course, really reminded me of Augusta, same type of grass, similar tough greens and just in very good shape. I really just enjoyed playing golf here. It's a golf course where you have to think, where you have to position your shots, where you have options. You can play aggressive and if you pull it off you're going to get rewarded, and if you miss it a few you're going to get punished, and I enjoy those kind of golf courses. I was fortunate enough to play very well on the weekend and make a few putts, but hit some good shots. Today I got off to a really good start with 3-under after 5 and then especially the birdie on 5 was incredible. I think that was a really tough pin. I was surprised they even put the pin over there behind the tall tree because if you're in the middle of the fairway coming in with a 6- or 7-iron there, you can't even aim at the flag, you have to go 20 feet right or something and then it slopes off further right. -

Caddie Guide

GETTING STARTED AS A CADDIE A GUIDE FOR BEGINNERS 49 Knollwood Road • Elmsford, NY 10523 www.mgagolf.org INTRODUCTION Caddieing is a great job. The money is good, you work outdoors and have an opportunity to meet successful and influential people, and you may even earn a college scholarship. Caddieing is an important job. It is part of golf’s heritage and part of its future. It is also a great way to learn the game of golf. This is YOUR book. Study it and ask your Caddie Manager or Golf Professional to explain anything that is not entirely clear. Knowledge of its contents will help make you a better caddie and valuable to the club and the golfers you serve. This book is published by the MGA Foundation. We believe caddies are an important part of the game of golf and together we are working to help keep young people like you active and interested in this great sport. THE CADDIE MANAGER The Caddie Manager is pivotal to the golf club industry with many responsibilities, which can materially affect the welfare of the club. The Caddie Manager is charged with the task of recruiting and scheduling caddies. He must also communicate effectively with the Golf Professional and other club staff members and can have a significant influence on the extent to which the membership enjoys the game. A professionally trained, knowledgeable and courteous group of caddies and a well-managed caddie program can help a club deal more effectively with slow play, significantly add to the number of enjoyable rounds of golf a n d enhance the club’s overall image of a first class operation. -

The Caddie Exam

THE CADDIE EXAM Western Golf Association www.wgaesf.org CADDIE EXAM Now that you have studied and reviewed the caddie manual and caddie orientation video, use this exam to test your caddie knowledge. This exam is worth 100 points. A minimum score of 85 points (85 percent) and above is considered passing. You have 30 minutes to complete. Thank you. The following statements are true or false. Read each statement carefully and circle the appropriate response. The True/False questions are worth 5 points each. 1. It is correct to pick up your player’s golf ball if you cannot identify the brand and number. True False 2. When the caddie manager assigns you a golfer, you may turn it down if you would like to caddie for someone else. True False 3. It is correct to demand from your player their golf club immediately after everyone has hit their tee shot. True False 4. In a greenside bunker, if your player fails to reach the putting green, stay with him/her and come back later to rake the sand or ask for another caddie’s assistance. True False 5. The caddie whose player is first to reach the putting green will be expected to handle the flagstick duties. True False Listed below are sentences followed by statements. Circle the letter(s) in front of all the correct statements. (There can be more than one correct answer for each question). The following questions are worth 5 points each. 6. Which of the following practices will help you become a good caddie? a. -

The Caddie Question in Edwardian Golf1 Wray Vamplew Introduction

Child Work or Child Labour? The Caddie Question in Edwardian Golf1 Wray Vamplew Introduction Child labour in sport is often regarded as a relatively modern phenomenon, usually with exploitative implications, involving third-world workers producing sporting goods, the abused bodies of communist bloc girl gymnasts, and teenage African footballers discarded when they failed to make the grade in Europe.2 Although historical examples are generally absent from the academic literature, there are late nineteenth and early twentieth-century instances in Britain in the use of boy jockeys in horseracing and, the subject of this chapter, the child caddie in golf.3 For the purposes of this chapter children are considered to be young persons under the age of sixteen, the line generally taken by golf clubs. Hence the discussion of child caddies is not confined to those still at school but also includes school leavers, many of whom could be as young as twelve.4 The perceived problems of such caddies were part of a wider issue in Britain. At the turn of the twentieth century there was concern that a growing demand for child labour in occupations such as errand boys, machine minders and industrial packers was creating a pool of young workers, trained for nothing else and destined to swell the ranks of casual labourers as they became older and lost their jobs to younger and cheaper boys who in turn faced the same fate.5 The list of jobs put forward by commentators as part of the ‘boy labour’ issue did not include the golf caddie, yet within golf the situation of the boy caddie had became recognised. -

The Caddie PLAYBOOK

The Caddie PLAYBOOK A guide to starting, building or perfecting your club’s youth caddie program PRODUCED BY THE WESTERN GOLF ASSOCIATION Table of Contents Introduction 3 Benefits of Youth Caddie Programs 4 Program Guidelines 5 Recruiting 6 Training Caddies 7 Classification 8 How to Assign Caddie Loops 9 How to Evaluate Performance 10 Caddie Compensation 11 Caddie Awards & Incentives 12 Promoting the Evans Scholarship 13 Introduction Caddying is an investment in the future of young men We recognize that many golf courses and clubs take and women. Caddies learn to work as a team on the alternative approaches to running a caddie program. golf course, helping one another and providing a great Many variables affect caddie programs, including service that amplifies the golfing experience. geographic location, number of golfers, number of caddies, etc. Please view these practices as general At the Western Golf Association, we provide affiliated recommendations rather than a formula for success that clubs with extensive resources for the development and all caddie programs must follow. operation of caddie programs at the club level. Still, there are basic elements that all successful caddie Materials available include: programs enjoy. These include: • Caddie training video • A dedicated caddie manager to recruit, train, select, • Caddie training manual pay, promote, encourage and discipline caddies • Caddie exam • An involved professional staff • Caddie operations manual • Interested golfers who are supportive of caddying • Brochures and posters promoting the benefits of • Committed young men and women caddie programs Our 22-minute caddie training video, Becoming a Great The WGA is committed to growing the game of golf Caddie, outlines a caddie’s duties before, during and through caddying, and we have dedicated staff to after a round of golf. -

PAIRINGS Updated 8-23-15

MGA Caddie Scholarship Pro-Am Winged Foot Golf Club (West Course), Mamaroneck, N.Y. Monday, August 24, 2015 PAIRINGS Updated 8-23-15 8:00 a.m. Shotgun Tee Time Name 1 8:00 a.m. Jim McGovern, White Beeches Golf & Country Club Pat Paolella, Bob Silvestri & Bob Dubrowski 1a 8:00 a.m. MGA Partner – MetLife Zoltan Gombas, Keith Busch, John Jankowski & Paul Cimino 2 8:00 a.m. Bryan Klinder, Hawke Pointe Golf Club Jan Price, Pat Schaible & Mark Haas 3 8:00 a.m. Brian Giordano, Sunningdale Golf Club Stephen Karotkin, Richard Schapiro & James Weil 3a 8:00 a.m. Mark Brazziler, Westhampton Country Club Robert Whittenberger, George Foley & Gary Smith 4 8:00 a.m. Mark Fretto, Montauk Downs Golf Course Douglas Maxwell, Gary Seigal & Brad Schneider 5 8:00 a.m. Mark McCormick, Suburban Golf Club Andrew Nordstrom, Doug Nordstrom & Frank Taranto 5a 8:00 a.m. Mark Giuliano, Fairmount Country Club Greg McGrath, James Schroeder & Lew Rauter 6 8:00 a.m. Jim Weiss, Cold Spring Country Club Mark Dobriner, Mike Langer & Jeff Garyn 7 8:00 a.m. Michael Kierner, Maplewood Country Club Larry Lewis, Barry Kronman & Barry Ostrowsky 7a 8:00 a.m. Matt Belizze, Southward Ho Country Club Fred O’Meally, Joe Macina & Mark Smith 8 8:00 a.m. Patrick Fillian, Echo Lake Country Club Dave Lieberman, Wally Parker & Kevin Fitzpatrick 9 8:00 a.m. Vaughan Abel, Hawke Pointe Golf Club Bob Wheatley, Jim Palson & Chris Bresler 9a 8:00 a.m. MGA Partner – Tiffany & Vineyard Vines Erik Liebler, Paul Cerami, Cory Crelan & Ryan Cannon The MGA….So You Can Play For MGA and Met Area results and scores visit www.mgagolf.org Follow us on Facebook | Twitter MGA Caddie Scholarship Pro-Am Winged Foot Golf Club (West Course), Mamaroneck, N.Y. -

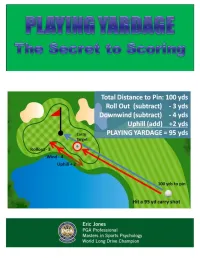

Playing Yardage: the Secret to Scoring

Playing Yardage: The Secret to Scoring One of the great secrets to scoring is understanding how to calculate true playing yardage. The good news is that playing yardage is easy to learn and use on the course. The bad news is that it is seldom taught. Most players have to learn about playing yardage the hard way - paying attention to shot after shot over hundreds of rounds to observe distances, trends and tendencies. Even then it is mostly guess-work. If you want to play better golf and consistently shoot lower scores it is critical to understand these two things: 1) how to calculate and use playing yardage, and 2) what your true carry yardage is for all your clubs. When you know your playing yardage you'll make better strategic decisions and you'll have a lot more confidence in your shots. You will hit your approach shots closer to the hole. We'll start with playing yardage. What Is Playing Yardage? Playing Yardage is not just how far it is to the pin. It's not how far you hit a given club. Here's playing yardage at its simplest: It's how far you intend to carry the ball. But of course calculating your playing yardage is a bit more complicated than just carry distance. In fact there's a formula you should be using. A formula you should use on every shot into the green and most other shots as well. A formula you should know so well that it comes as naturally as breathing. Here is the Playing Yardage Formula: Distance to pin Less: Roll-out Plus or minus Wind Plus or minus Elevation Plus or minus lie and stance Equals Playing Yardage The distance to the pin is the starting point. -

The Caddie PLAYBOOK

The Caddie PLAYBOOK A guide to starting, building or perfecting your club’s youth caddie program PRODUCED BY THE WESTERN GOLF ASSOCIATION Table of Contents Introduction 3 Benefits of Youth Caddie Programs 4 Program Guidelines 5 Recruiting 6 Training Caddies 7 Classification 8 How to Assign Caddie Loops 9 How to Evaluate Performance 10 Caddie Compensation 11 Caddie Awards & Incentives 12 Promoting the Evans Scholarship 13 Introduction Caddying is an investment in the future of young men We recognize that many golf courses and clubs take and women. Caddies learn to work as a team on the alternative approaches to running a caddie program. golf course, helping one another and providing a great Many variables affect caddie programs, including service that amplifies the golfing experience. geographic location, number of golfers, number of caddies, etc. Please view these practices as general At the Western Golf Association, we provide affiliated recommendations rather than a formula for success that clubs with extensive resources for the development and all caddie programs must follow. operation of caddie programs at the club level. Still, there are basic elements that all successful caddie Materials available include: programs enjoy. These include: • Caddie training video • A dedicated caddie manager to recruit, train, select, • Caddie training manual pay, promote, encourage and discipline caddies • Caddie exam • An involved professional staff • Caddie operations manual • Interested golfers who are supportive of caddying • Brochures and posters promoting the benefits of • Committed young men and women caddie programs Our 22-minute caddie training video, Becoming a Great The WGA is committed to growing the game of golf Caddie, outlines a caddie’s duties before, during and through caddying, and we have dedicated staff to after a round of golf. -

Address the Position of One's Body Taken Just Before the Golfer Hits the Ball

INTERNATIONAL GOLF FEDERATION Maison du Sport International Av. de Rhodanie 54 1007 Lausanne, Switzerland Tel. +41 21 623 12 12 Fax +41 21 601 6477 www.igf.golf TERM DEFINITION Address The position of one's body taken just before the golfer hits the ball. A player has "addressed the ball" when he/she has grounded his/her club immediately in front of or immediately behind the ball, whether or not he/she has taken his/her stance. After hole See "thru". Aggregate score See "total score". Albatross See "double eagle". Approach shot The last shot that lands on or around the green, or in the hole, that does not begin on or around the green. Apron See "fringe". Back nine Holes 10 through 18. Backspin A reverse spin naturally imparted on the ball by a club (other than a putter) when a stroke is made, which can cause the ball to stop quickly when it lands and often move in the opposite direction. Backswing The backward portion of the swing prior to making a stroke at the ball. Birdie A score of 1 under par for a hole. Bogey A score of 1 over par for a hole. Bunker A hazard consisting of a prepared area of ground, often a hollow, from which turf or soil has been removed and replaced with sand or the like. Also unofficially referred to as a "sandtrap". Caddie A person who assists the player in accordance with the rules, which may include carrying or handling the player's clubs during play. The caddie may give the player advice. -

2019 Golf Fees Resident

- 2019 Resident Cards - - Save Money This Spring! $199 Spring Special – “Best Deal in Golf” - Pre-Season Discount Deadline—March 15 Who qualifi es for a Resident Card? Get your 2019 golf season off to a great start with the $199 Applicants must reside within the corporate limits of the Spring Special. Play the 9-hole & 18-hole courses and get Village of Glen Ellyn. Apply in person at the Golf Shop to unlimited weekday golf thru April, along with 50% off weekday have your photo taken. Proof of residency is required. green fees in May. If you don’t play at least $199 in FREE Resident Cards must be renewed annually and expire (April) and HALF PRICE (May) green fees, we will credit you on December 31. the full difference. The Spring Special cannot be combined What are the benefi ts of a Resident Card? with any other offers or discounts. Green fee discount does Resident Card holders receive discounts on their green not apply on Memorial Day, Monday, May 27. Optional carts fees, and receive preferred access to tee time reservations. are available at the regular fee. You can use your “Village Links Card” immediately. Why should I apply for my Resident Card now? Adult Resident Cards are $10 before March 15 and $20 thereafter. Junior Cards are $5 and $10 after March 15. Cards must be renewed annually and expire on December 31. - 2019 Multi-Play & V.I.P. Cardholder - Multi-Play Resident Discount Rounds RESIDENT REGULAR V.I.P. Multi-Play Resident Discount Rounds—Resident card 2019 GOLF FEES CARD (NON-RESIDENT) CARD holders can pre-purchase 20 or more 18-hole green fees at a discounted multi-play rate. -

Where to Play Golf

Where to Play Golf • Choosing the courses – Play whatever golf courses you want to play! Have a look through Scottish golf map or the full list of course reviews on my site to plan out your trip. My advice would be to play all of the famous courses you want, but try to work in a few lesser-known gems. You’ll be amazed by how fondly you look back on the choice to play a local gem after your trip. • Tee times - Getting tee times on Scottish golf courses is a very straightforward process. 99% of golf courses in Scotland are open to the public. Some courses may limit their visitor play to only a few days per week (Muirfield and Troon etc.), but nearly all welcome guests with open arms! You can call every course, email most courses, and even use online booking systems for some of the tech friendly courses. Emailing particularly well-known clubs months in advance typically pays off. Also, I have written an entire post on getting a tee time on the St Andrews Old Course. • Ranges – Keep in mind during your visit that most traditional Scottish golf courses don’t have a practice range. The real tip here has to do with St Andrews. The St Andrews Links Trust does have a range, but it is a 20-minute walk from the first tee of the Old Course – don’t expect to hit a few balls 10 minutes before your tee time. During high season, a shuttle runs from the range to the first tees of the links courses in town! • Hickory Golf – The experience of playing a round of golf with hickory clubs taps into a purer form of the game.