2017 Kansas Health Foundation Grant Report About the Center for Engagement and Community Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Construction Survey

CONSTRUCTION SURVEY Company City State Primary Type Sq. ft. Cost A/E Comp. Product (000) ($ Mil.) Date 7-Eleven (Op. Norris Food Svcs.) Bohemia NY Food distribution New 130 2/09 A Abbyland Foods Inc. Abbotsford WI Meats New 85 20 Excel Engineering 3/08 Advance Food Co. Enid OK RTE products Ren. 8 2.5 Gleeson Constructors LLC 10/08 Affiliated Foods Midwest Cooperative Kenosha WI Distribution center Exp. 731 99 AgPlus Cooperative Kindred ND Soybean oil New 130 Albertville Quality Foods Albertville AL Poultry New VCP&A 2/09 Alb-Gold/Bionade Amana IA Noodles/beverages New 122 40 Algood Food Co. Louisville KY Peanut butter, jams, jellies Exp. 8 3 Allen Flavors Inc. South Plainfield NJ Flavor extracts/dist./whse. Exp. 85 Allied Frozen Food Storage Inc. Niagara Falls NY Frozen foods New 2 Always Bagels Lebanon Cnty. PA Bagels New 68 21.5 09 American Blanching Co. Fitzgerald GA Peanut products Exp. 22 1 American Food Resources Nashville NC Specialty canning Exp. 50 3 American Proteins Hanceville AL Poultry meals Exp. 2 10 Ann’s House of Nuts/Olympus Partners Robersonville NC Roasted nuts Exp. 2 Appeeling Fruit Leesport PA Sliced fruit Ren. 25 1.5 Webber/Smith Associates Inc. 8/09 Archer Daniels Midland Co. Hazleton PA Cocoa New 500 Arizona Canning Co. Tucson AZ Distribution center Ren. 90 Stellar 8/09 Artesian Fresh Inc. Le Roy MN Bottled water New 21 Associated Brands Medina NY Private-label foods Exp. 08 Associated Food Stores Salt Lake City UT Cold storage Exp. 60 16 Food Tech 11/08 Aurora Organic Dairy Platteville CO Dairy Exp. -

The Nebraska Sandhills Food Desert: Causes, Identification, and Actions Towards a Resolution

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Community and Regional Planning Program: Student Projects and Theses Community and Regional Planning Program 5-2012 The Nebraska Sandhills Food Desert: Causes, Identification, and Actions towards a Resolution Andrew Thierolf University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/arch_crp_theses Part of the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Thierolf, Andrew, "The Nebraska Sandhills Food Desert: Causes, Identification, and Actions owart ds a Resolution" (2012). Community and Regional Planning Program: Student Projects and Theses. 11. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/arch_crp_theses/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Community and Regional Planning Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Community and Regional Planning Program: Student Projects and Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE NEBRASKA SANDHILLS FOOD DESERT: CAUSES, IDENTIFICATION, AND ACTIONS TOWARDS A RESOLUTION by Andrew Thierolf A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Community and Regional Planning Major: Community and Regional Planning Under the Supervision of Professor Gordon Scholz Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2012 THE NEBRASKA SANDHILLS FOOD DESERT: CAUSES, IDENTIFICATION, AND ACTIONS TOWARDS A RESOLUTION Andrew Thierolf, M.C.R.P. University of Nebraska, 2012 Advisor: Gordon Scholz Declining populations over the past several decades have created issues for residents in many rural areas. A serious concern is the emergence of “food deserts,” areas where people do not have sufficient access to nutritious foods. -

Proudly Serving Nebraska Grocers for Over 100 Years. 1-800-333-7340 1-402-592-9262

TheVoiceVoice ofof thethe NebraskaNebraska GroceryGrocery IndustryIndustry March/April 2010 AWG Distribution Center AWG Trade Area RetaileR Owned VMC Distribution Center 21 States And Growing associated wholesale Grocers: Florida Iowa • Home of independent retailers Louisiana Mississippi • Focused on our retailers’ success Virginia Indiana • Dedicated to serving Nebraska Illinois Georgia Tennessee our members in 21 states Alabama Kentucky • Established in our country’s heartland Texas New Mexico Kansas Ohio for over 83 years Missouri North Carolina • Financially sound balance sheet Oklahoma South Carolina Arkansas • Strong in numbers serving over 1,800 retail stores • We own our own warehouses • Award winning house brands: 8 Distribution Centers Best Choice, Always Save and Clearly Organic 5 Million sq. ft. • Specialized facilities: HBC/GM, Pharmacy, Specialty Foods, Authentic Kansas City Ft. Worth Hispanic, Dollar Merchandise Bill Quade, Sr. V.P. Tom Arledge, Sr. V.P. • Real Estate, Store Engineering, Division Manager Division Manager (913) 288-1280 (817) 568-3751 Design Services Springfield Oklahoma City Maurice Henry, Sr. V.P. Tim Bellanti, Sr. V.P. Division Manager Division Manager AWG Stands Out From The Competition (417) 875-4230 (405) 518-3329 Memphis Nashville “Profit From Our Experience” Gary Jennings, Sr. V.P. Milton Milam, Sr. V.P. Division Manager Division Manager (662) 342-4108 (615) 859-8201 Chairman of the Board: Bill Hueneman 5th Street IGA Vice Chairman of the Board: Bob Maline Maline’s Super Foods CONTENTS Treasurer: -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A)

FEB 2 6 2000 NPS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service MAR 1 2 2008 National Register of Historic Places NA HtGISIfcH OF HISTORIC PLA 3ES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SFRVIHF This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Grocers Wholesale Company Building other names/site number Sears and Roebuck Farm Store 2. Location street & number 22 West Ninth Street N/A1 not for publication city or town __ Des Moines ___ [N/A1 vicinity state Iowa code IA county Polk code 153 zip code 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination LJ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [X] meets LJ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

2016 Annual Report

BOARD OF DIRECTORS Barry Queen, Chairman David Ball Danny Boyle Jim Brown John Clarke Victor Cosentino Queen’s Enterprises - Paola, KS Four B Corp Country Boy Markets Doc’s Food Stores County Fair Cosentino’s Kansas City, KS Harrah, OK Bixby, OK Food Store Prairie Village, KS Mitchell, SD Don Woods, Jr., Vice-Chairman Kim Eskew Alan Larsen Jay Lawrence Alan McKeever Chuck Murfin Woods Supermarkets - Bolivar, MO Harp's Foods Houchens Industries Lawrence Brothers McKeever’s Ozark Supermarkets Springdale, AR Bowling Green, KY Sweetwater, TX Independence, MO Ozark, MO James Neumann Dave Nicholas Pat Raybould Jeff Reasor Randy Stepherson Erick Taylor Dale Trahan Valu Market, Inc. Nicholas B&R Stores Reasor’s Superlo Foods RPCS, Inc. Dale Trahan Louisville, KY Supermarkets Lincoln, NE Tahlequah, OK Memphis, TN Springfield, MO Enterprises Boonville, MO Rayne, LA DEAR SHAREHOLDERS March 22, 2017 Dear Shareholders, combined efforts and Your Board of Directors and management are a common purpose. pleased to present the audited results for our fiscal Beyond just our year 2016. Consolidated company sales reached operating results, another record of $9.18 billion, up 2.78%. Total year- AWG and VMC members also benefited from end patronage after retainage was $201.7 million, meaningful cost of goods reductions. In 2016, another record, which was 2.78% of qualifying sales. our merchant team worked closely with our Total distribution including patronage, allowances vendor partners to establish and build upon and interest back to members was $546.5 million, relationships that would further leverage an increase of $2.1 million even after reflecting an our collective membership’s scale of over increase in the amount of promotional allowances $20 billion in retail sales. -

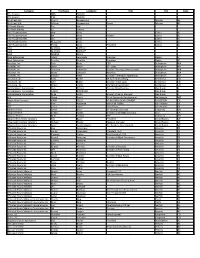

Participating Distributors Revised 05.26.15 Page 1 of 13

Participating Distributors Revised 05.26.15 Page 1 of 13 Recently Added Distributors Blair’s Market Dick’s TDL Group Corp (Tim Hortons) Blazer’s Fresh Foods DJ’s Inc Calgary Food Bank Blue Mountain Foods DJ’s Pilgrim Market The North West Company Bob’s Supermarket Don’s Market M&M Meat Shops Ltd. Bob’s Valley Don’s Thriftway T.I.G.O. Trading Bowman’s Double D Market Devash Farms Bradley’s Bestway Dove Creek Superette KCCP Distribution Company Broulim’s Market Downey Food Center Nutricion Fundemental Burney & Company Dry Creek Stations Pasquier Busy Corner Market Duane’s Foodtown Horizon Distributors Ltd. Buy Low Market Duckett’s Market Fruiticana Produce Ltd. Cactus Pete’s Country Store El Mexicano Market Dollarama L.P. Caliente Store El Rancho Market Camas Creek Country Store El Rodeo Market 99 Cents Only Stores Canyon Foods Elgin Foodtown Affiliated Foods Midwest Carter’s Market Emigrant General Store Affiliated Foods Inc - Amarillo Cash and Carry Foods Etcheverry’s Foodtown Ahold Cedaredge Foodtown F T Reynolds American Sales Company Central Market Familee Thriftway Giant Foods Chappel’s Market Family Foods Martin’s Foods Chuck Wagon General Family Market Stop & Shop Clarke’s Country Market Farmer’s Corner Albertson’s LLC Clark’s Market Farmer’s Market ACME Clinton Market Finley’s Food Farm Aldi Colter Bay Store Flaming George Market Asian Imports/Navarro Transportation Columbine Market Food Ranch Bestway Associated Food Stores (Far West) Cook’s Foodtown Food RoundUp A&A Market Cooperative Mercantile Corp Food World Thriftway Adamson’s Corner Market Fortine Merc. Alamo Store Cottonwood Market Fresh Approach Aldapes Market Cottonwoods Foods Fresh Market Allen’s Inc. -

8:16-Cv-00465-JFB-MDN Doc # 39 Filed: 02/03/17 Page 1 of 7

8:16-cv-00465-JFB-MDN Doc # 39 Filed: 02/03/17 Page 1 of 7 - Page ID # <pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEBRASKA AFFILIATED FOODS MIDWEST COOPERATIVE, INC., a Nebraska corporation; and ASSOCIATED WHOLESALE GROCERS, INC., Plaintiffs, 8:16CV465 vs. SUPERVALU INC., a Delaware MEMORANDUM AND ORDER corporation, Defendant, Borowiak IGA Foodliner, Inc., Intervenor. This matter is before the Court on the motion to intervene filed by Borowiak IGA Foodliner, Inc. (“Borowiak”). (Filing No. 10). Borowiak filed a brief in support of the motion. (Filing No. 11) Borowiak also filed a statement of interest in support of intervention (Filing No. 12). In response, plaintiff Affiliated Foods Midwest Cooperative, Inc. (“AFM”) filed a brief in opposition to the motion to intervene. (Filing No. 27). The defendant, SuperValu Inc. (“SuperValu”) has not filed a response to the motion. The plaintiff filed this action alleging that SuperValu tortiously interfered with the supply agreement between Borowiak and the plaintiff. The defendant, SuperValu, disagrees and argues that AFM cannot sustain a claim for tortious interference. SuperValu additionally asserts that competition for Borowiak’s business is a matter of public interest since society is benefitted by lawful competition. Plaintiff also filed a motion for a temporary restraining order (“TRO”) against SuperValu. BACKGROUND At all material times herein the plaintiff, AFM, is a grocery store chain which entered into a supply agreement with Borowiak. The defendant, SuperValu, is a 8:16-cv-00465-JFB-MDN Doc # 39 Filed: 02/03/17 Page 2 of 7 - Page ID # <pageID> Minnesota-based wholesaler which served as Borowiak’s primary grocery supplier until Borowiak decided to switch to AFM. -

Hand Sanitizers: Not a Replacement for Handwashing in Food Service Settings

TheVoiceVoice ofof thethe NebraskaNebraska GroceryGrocery IndustryIndustry January/FebruaryJanuary/February 20102010 ™ It’s like a store... for your store. From retail systems to sanitation. From merchandising to marketing. We have what you need to run a profitable store. Want to know more? Call Louis Stinebaugh 402-537-6637 or Bob Destefano 402-537-6627 You can also visit: www.nashfinch.com/services.html AWG Distribution Center AWG Trade Area RetaileR Owned VMC Distribution Center 21 States And Growing associated wholesale Grocers: Florida Iowa • Home of independent retailers Louisiana Mississippi • Focused on our retailers’ success Virginia Indiana • Dedicated to serving Nebraska Illinois Georgia Tennessee our members in 21 states Alabama Kentucky • Established in our country’s heartland Texas New Mexico Kansas Ohio for over 83 years Missouri North Carolina • Financially sound balance sheet Oklahoma South Carolina Arkansas • Strong in numbers serving over 1,800 retail stores • We own our own warehouses • Award winning house brands: 8 Distribution Centers Best Choice, Always Save and Clearly Organic 5 Million sq. ft. • Specialized facilities: HBC/GM, Pharmacy, Specialty Foods, Authentic Kansas City Ft. Worth Hispanic, Dollar Merchandise Bill Quade, Sr. V.P. Tom Arledge, Sr. V.P. • Real Estate, Store Engineering, Division Manager Division Manager (913) 288-1280 (817) 568-3751 Design Services Springfield Oklahoma City Maurice Henry, Sr. V.P. Tim Bellanti, Sr. V.P. Division Manager Division Manager AWG Stands Out From The Competition (417) 875-4230 (405) 518-3329 Memphis Nashville “Profit From Our Experience” Gary Jennings, Sr. V.P. Milton Milam, Sr. V.P. Division Manager Division Manager (662) 342-4108 (615) 859-8201 Chairman of the Board: Bill Hueneman 5th Street IGA Vice Chairman of the Board: Bob Maline Maline’s Super Foods CONTENTS Treasurer: Larry Baus Village Market, Wagner’s Food Pride features & departments advertisers Secretary: Richard Cosaert 18 Advantage Sales 3 Nebraska Food News.. -

2010-Year in Review-082610.Indd

A MESSAGE FROM YOUR CHAIRMAN As one door closes, another door opens: a saying which proved true in 2009/2010 as we ushered an old decade out and a new one in. A similar transition in leadership transpired with the National Grocers Association (N.G.A.). After 28 years of dedication and leadership to the independent grocery industry, President and CEO Tom Zaucha transitioned the organization to Peter Larkin. Larkin is the former President and CEO of the California Grocers Association (CGA). On behalf of the N.G.A. Board of Directors we say welcome Peter! Time and again, the independent grocers have been challenged by doubters, regulators, mother nature and more. Yet as each challenge is tossed at our industry, we fi ght back. The National Grocers Association steps forward and tells our story – the story of thousands of innovative retailers and their employees across the country who strive every day to serve the communities in which they live. The independent grocers have a voice and the National Grocers Association is here to get that voice and message heard. Together this year, we advanced the cause of independent grocery retailers and wholesalers on many fronts – from regulation to legislation, from operational issues to food safety. One of the things I am most proud of is the way grocers from different states came together to speak with one voice and raise the profi le of today’s independent community-focused retailer. In the following pages, you will learn what your Association accomplished in 2009/2010. I expect even greater success in 2011. -

2013 List of Registrants

Company FirstName LastName Title City State 4T's Grocery ANN TAYLOR 4T's Grocery TIM TAYLOR 5th Street IGA Sherry Huenemann Minden NE 5th Street IGA William Huenemann Owner Minden NE 99 Ranch Market Tee Jaw 99 Ranch Market Ty Truong A & R Supermarkets Ann Davis Calera AL A & R Supermarkets Bill Davis Partner Calera AL A & R Supermarkets Jan Davis Calera AL A & R Supermarkets Margarita Davis Calera AL A & R Supermarkets Phillip Davis President Calera AL AAIA MICHAEL BARRATT AAIA MICHAEL BARRATT AAIA ARLENE DAVIS Abco Enterprises Adam Sepulveda Manager Ogden VT Abco Enterprises Suzette Sharifan President Ogden VT Accelitec, Inc. Tom Bartz CEO Bellingham WA Accelitec, Inc. Steve Byron VP - Sales Bellingham WA Accelitec, Inc. Christine Schneider Director -Business Development Bellingham WA Accelitec, Inc. Marty Schroder Accelitec Bellingham WA Accelitec, Inc. Edward West Director - Merchant Operations Bellingham WA AccuCode, Inc. Todd Baillie VP Sales & Marketing Centennial CO AccuCode, Inc. John Butler Director of AO: Apps Centennial CO AccuCode, Inc. Robyn Crotty Marketing Coordinator Centennial CO Ace Hardware Corporation Curt DeHart Director New Business Oak Brook IL Ace Hardware Corporation CARLO MORANDO Oak Brook IL Ace Hardware Corporation Mike Smith Grocery Channel Manager Oak Brook IL ACS Chuck Daniel Dir of Corporate Development Nottingham MD Action Retail Services JOHN GILLIS VP BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT FULLERTON CA ADT Teal Hausman Jack of all Trades San Antonio TX ADT Cesar Lopez Sales/Buyer San Antonio TX Advance Pierre David Minx VP Strategic Sourcing Cincinnati OH Advance Pierre Shawn Sparks Director of Strategic Sourcing Enid OK Advance Pierre Mike Zelkind SVP Cincinnati OH Advanced Inventory Solutions Tim Bayer President Grand Rapids MI Advanced Inventory Solutions Richard Heetai Regional Manager Grand Rapids MI Advanced Inventory Solutions Steve Southerington Dir. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of NEBRASKA AFFILIATED FOODS MIDWEST COOPERATIVE, INC., a Nebraska Corporat

8:16-cv-00465-JFB-MDN Doc # 55 Filed: 05/30/17 Page 1 of 7 - Page ID # <pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEBRASKA AFFILIATED FOODS MIDWEST ) COOPERATIVE, INC., a Nebraska ) corporation, and ASSOCIATED ) WHOLESALE GROCERS, INC., ) 8:16CV465 ) Member Case Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ORDER SUPERVALU INC., a Delaware ) corporation, ) ) Defendant. ) BOROWIAK IGA FOODLINER, INC., ) ) Plaintiff/Counter Defendant, ) ) v. ) AFFILIATED FOODS MIDWEST ) 8:16CV466 COOPERATIVE, INC., and ) Lead Case ASSOCIATED WHOLESALE ) GROCERS, INC., ) ORDER ) Defendants/Third-Party ) Plaintiffs/Counter Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) TREVOR BOROWIAK, ) ) Third Party Defendant. ) This matter comes before the Court on the Motion to Strike Plaintiff’s Jury Demand in the Lead Case (Filing No. 37) filed by the Lead Case defendants, Affiliated Foods Midwest Cooperative, Inc. (“AFM”) and Associated Wholesale Grocers (“AWG”). AFM/AWG argue 8:16-cv-00465-JFB-MDN Doc # 55 Filed: 05/30/17 Page 2 of 7 - Page ID # <pageID> that the Lead Case plaintiff, Borowiak IGA Foodliner, Inc. (“Borowiak”), waived its right to a jury trial in pre-litigation written agreements with AFM. The Court will grant the motion. BACKGROUND Borowiak is a grocery store chain currently operating seven local supermarkets in southern Illinois. (Filing No. 1 at p. 2). On December 29, 2015, Borowiak and AFM entered into a Supply Agreement in which AFM agreed to supply Borowiak with foodstuffs and other items sold to retail grocers. (Filing No. 38-1). On the same date, in connection with the Supply Agreement, Borowiak executed a Promissory Note (Filing No. 38-3) and a Security Agreement (Filing No. -

Co Op 100 WELCOME to the CO OP 100 in Releasing the Annual NCB Co-Op 100®, National Cooperative Bank Proudly Highlights America’S Top 100 Cooperatives

A BETTER WORLD The 2016 NCB ® Co op 100 WELCOME TO THE CO OP 100 In releasing the annual NCB Co-op 100®, National Cooperative Bank proudly highlights America’s top 100 cooperatives. These member- owned, member-controlled businesses generated revenues of Equal Exchange Co-op $223.8 billion in 2015. Like investor owned firms (IOFs), cooperatives While cooperatives may offer the same kinds of consumers in mind while conducting business. employ millions of people, pay taxes and give back goods or services as publicly traded firms, they use Those surveyed also believed that co-ops are to their communities. They are organized under distinctly different business models. Cooperatives committed to and involved in their communities; bylaws and articles of incorporation. They provide are owned and controlled by the very people who are committed to providing the highest quality valuable products and services, trade in the global use and benefit from their goods and services: the service to their customers; and can be counted on market and deal with competition. members. Having a vested interest in the co-op to meet their customers’ needs. fosters a natural closeness and accountability And like, IOFs, cooperatives feel the pressure of a between owner/members and management. Cooperatives remain a trusted, viable and deflated stock market and commodity pricing. As a successful business model. They build jobs and result, co-op revenues for 2015 dropped 8.6% from Cooperatives also differ from IOFs in how they are community. Cooperatives Build A Better World. the previous year mainly in the agricultural sector. perceived by the public.