Robert Graves and Irish Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

There Is No “Unless” for Poets’:* Robert Graves and Postmodern Thought Nancy Rosenfeld

‘There is no “unless” for poets’:* Robert Graves and Postmodern Thought Nancy Rosenfeld Robert Graves’s place in twentieth century literature and thought is much more central than the relatively marginal status accorded him in standard critical accounts. Graves is best known as the author of historical novels. His I, Claudius, produced as a BBC television series in the 1970s, and its sequel Claudius the God and his Wife Messalina made his name a household word. Yet Graves was a twentieth century Renaissance man: his body of work includes poetry – Graves viewed himself as a poet first and foremost – more than a dozen historical novels, autobiography, studies of mythology and ethnography, writing guides, translation, social commentary, literary criticism. Graves’s autobiography Good-bye to All That is one of the most influential memoirs to come out of the First World War. His Greek Myths remains a basic text in comparative literature studies. Generations of aspiring poets have sought guidance in The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth. Poetry, Graves argued in Lecture One of the Oxford Chair of Poetry series delivered in 1964, ‘is a way of life, a vocation or a profession’, even though it is not ‘operationally organized’ as are the professions of medicine, law, architecture, pedagogy.1 This and more: the imperative of questioning ‘every word and sound and implication in a poem either read or written’ stands in direct opposition to ‘present trends in politics, economics and ethics which are wholly inimical to the appearance of new poets, or the honourable survival of those who may have already appeared.’ The true poets are always/already tempered by poetic principle, which is ‘a simple, obstinate belief in miracle: an asseveration of * Robert Graves, Poetic Craft and Principle (London: Cassell, 1967), p. -

Robert Graves1 Deya William Graves5 Oundle

Robert Graves1 Deya Robert Graves3, Deya William Graves5 Oundle School November 15, 1957 Dearest Wm : Good luck in your interview. If you are wholly at your ease - and why not? - all will go well. But try to raise some sort of enthusiasm for your proposed career: dont-care-ism doesn't go down well. There's never been so wet a November since - since last time - but we have had about three sunny days, and I even bathed three days ago at Can Floque. The best news is getting 3 bottles of butagaz smuggled from France, which means no more dirty carbon in the kitchen until the supply gives out. We hope to spend a few days in Austria with Jenny on the way to Jugland, but she is all snarled up with the Bevan libel case (on November 21st) & doesn't answer letters. She was very nice to Lucia and Juan on the way through. I expect my Goodbye To All That will create a stir again as it did in 1929 when it first came out - Canellun was built on the spoils. The Sunday Express reviewer cabled could he fly out & interview me. I cabled "yes: but you'll have to come out to Deya", & that's the last I've heard. The pups are eating raw meat now & are very large & fat & active; Mother spends most of her time trying to make them make little puddles on the Baleares. Castor is trimming the trees in the garden; the oranges nearly ripe. The stupid lilac thinks it is spring & is flowering like the pear tree. -

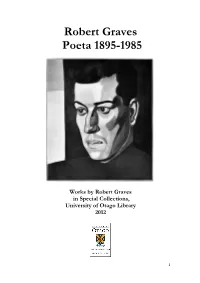

Works by Robert Graves in Special Collections, University of Otago Library 2012

Robert Graves Poeta 1895-1985 Works by Robert Graves in Special Collections, University of Otago Library 2012 1 There is no now for us but always, Nor any I but we – Who have loved only and love only From the hilltops to the sea In our long turbulence of nights and days: A calendar from which no lover strays In proud perversity. Envoi. (Collected Poems, 1975) On the headstone that marks his grave at Deyá, Marjorca, there is the simple: ‘Robert Graves Poeta 1895-1985’. And it was this aspect that attracted Charles Brasch, editor, patron and poet, to the works of Graves, calling him ‘among the finest English poets of our time, one of the few who is likely to be remembered as a poet.’ Indeed, not only did Brasch collect his own first editions volumes written by Graves, but he encouraged the University of Otago Library to buy more. Thanks to Brasch, Special Collections at the University of Otago now has an extensive collection of works (poetry, novels, essays, children’s books) by him. Born at Wimbledon in 1895, Graves had an Irish father, a German mother, an English upbringing, and a classical education. Enlisting in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, Graves faced the horrors of World War I. He was wounded by shrapnel, left for dead and later able to read his own obituary in The London Times. In 1929, he penned Goodbye To All That, his war-time autobiography which gave him success and fame. And aside from his regular output of poetry books, he wrote historical novels such as I Claudius (1934) and Claudius the God (1934), The White Goddess (1948), the heady study on matriarchal worship and poetry that in the sixties became a source book for readers of the Whole Earth Catalog, and the very successful The Greek Myths (1955). -

Robert Graves

Robert Graves Robert Graves The University of San Francisco aims “to cultivate the heart that it may love worthwhile things.” First editions with inscriptions and corrected galley proofs of such a writer as Robert Graves, Professor of Poetry at Oxford, have the magic to thrill the student, to give him a love of learning sufficient for a lifetime. Therefore, the University and the Gleeson Library Associates thank Mr. Walter Bartmann for adding to the cultivation of our students by the donation of his collection of first editions of Robert Graves. All titles of this collection are contained in the checklist except ephemera. Titles with asterisk are not in the collection but will be added. ANNUAL MEETING Gleeson Library Associates APRIL 29, 1962 A Checklist Robert Graves Section I Poetry, Novels and Essays 1916 Over the Brazier. David and Goliath. With author's book-plate. 1917 Fairies and Fusiliers. 1919 The White Cloud.* 1920 Treasure Box. Privately printed and signed. 1921 The Pier-Glass. 1922 On English Poetry. Robert Graves http://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.0020390s 1923 The Feather Bed. No. 82 of 250 signed. Whipperginny. 1924 Mock Beggar Hall. The Meaning of Dreams. 1925 Welchman's Hose. 525 copies. John Kemp's Wager: A Ballad Opera. My Head! My Head! Contemporary Techniques in Poetry: a Political Analogy. Poetical Unreason and Other Studies. 1926 Another Future of Poetry.* Impenetrability. 1927 Poems 1914–1926. No. 18 of 115 signed. The English Ballad. Lars Porsena or The Future of Swearing. Lawrence and the Arabs. 1928 Mrs. Fisher or The Future of Humour. -

Robert Graves - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Robert Graves - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Robert Graves(1895 - 1985) Robert Graves was born in 1895 in Wimbledon, a suburb of London. Graves was known as a poet, lecturer and novelist. He was also known as a classicist and a mythographer. Perhaps his first known and revered poems were the poems Groves wrote behind the lines in World War One. He later became known as one of the most superb English language 'Love' poets. He then became recognised as one of the finest love poets writing in the English language. Members of the poetry, novel writing, historian, and classical scholarly community often feel indebted to the man and his works. Robert Graves was born into an interesting time in history. He actually saw Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession at the age of two or three. His family was quite patriotic, educated, strict and upper middle saw his father as an authoritarian. He was not liked by his peers in school, nor did he care much for them. He attended British public school. He feared most of his Masters at the school. When he did seek out company, it was of the same sex and his relationships were clearly same sex in orientation. Although he had a scholarship secured in the classics at Oxford, he escaped his childhood and Father through leaving for the Great War. Graves married twice, once to Nancy Nicholson, and they had four children, and his second marriage to Beryl Pritchard brought forth four more children. -

Neurasthenia, Robert Graves, and Poetic Therapy in the Great War Juliette E

Student Publications Student Scholarship Fall 2017 Neurasthenia, Robert Graves, and Poetic Therapy in the Great War Juliette E. Sebock Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Cultural History Commons, European History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Military History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Sebock, Juliette E., "Neurasthenia, Robert Graves, and Poetic Therapy in the Great War" (2017). Student Publications. 588. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/588 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neurasthenia, Robert Graves, and Poetic Therapy in the Great War Abstract Though Robert Graves is remembered primarily for his memoir, Good-bye to All That, his First World War poetry is equally relevant. Comparably to the more famous writings of Sassoon and Owen, Graves' war poems depict the trauma of the trenches, marked by his repressed neurasthenia (colloquially, shell-shock), and foreshadow his later remarkable poetic talents. Keywords Robert Graves, poetry, great war, World War I, shell-shock Disciplines Cultural History | European History | Literature in English, British Isles | Military History Comments Written for HIST 219: The Great War. Creative Commons License Creative ThiCommons works is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This student research paper is available at The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ student_scholarship/588 Neurasthenia, Robert Graves, and Poetic Therapy in the Great War Juliette Sebock By 1914, hysterical disorders were easily recognisable, in both civilian and military life. -

An Emperor in Translation: Suetonius, Claudius, and Robert Graves

An Emperor in Translation: Suetonius, Claudius, and Robert Graves About twenty years after Robert Graves wrote the novels I, Claudius and Claudius the God, based on the life of the emperor Claudius, he published a translation of Suetonius’ De Vita Caesarum under the title The Twelve Caesars. While Graves’ translation is generally faithful, it is colored by his personal ideas about Claudius, which he expresses not only through his two novels, but also in interviews, letters, and other literary works. I argue that in The Twelve Caesars, Graves subtly inserts a new and improved, sympathetic Claudius into Suetonius’ more negative depiction. To show this, I will compare episodes in Suetonius to parallel episodes in the novels, demonstrating Graves’ manipulation of events, themes, and—above all—language. After giving a brief overview of our evidence for Graves’ views on Claudius, I will turn to the two letters of Augustus concerning Claudius, which are quoted by Suetonius and reworked in I, Claudius. These are not merely episodes in Suetonius that Graves has adapted, but recognizably the very same letters. In fact, in the second letter, Graves’ translation in The Twelve Caesars is less precise than his rendering of it in the novel. Next, I focus on the episode in which Claudius is declared emperor, pointing out that in The Twelve Caesars, Graves leaves out the damning phrase prae metu “because of fear” (Suet.Div.Claud.10.2) to explain Claudius’ actions. Finally, I turn to chapters 14 and 15 in Suetionus, in which Claudius’ law court activity occurs. I argue that Graves’ translation renders Claudius much more capable than the Latin implies and is highly influenced by the court scenes in Claudius the God. -

Boston College Collection of Siegfried Sassoon Before 1930-1964 MS.1986.051

Boston College collection of Siegfried Sassoon before 1930-1964 MS.1986.051 https://hdl.handle.net/2345.2/MS1986-051 Archives and Manuscripts Department John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Biographical note ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 I: Manuscript ............................................................................................................................................... 6 II: Correspondence ...................................................................................................................................... 6 III: Printed works ....................................................................................................................................... -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

Graves and the Grocery Philip Stewart

Graves and the Grocery Philip Stewart Robert Graves and his wife Nancy Nicholson lived on Boars Hill from late in 1919 to June 1921, in what is now called Dingle Cottage, at the bottom of John Masefield‟s garden. In October 1920, Nancy opened a grocer‟s shop in partnership with the Hon. Mrs Michael Howard. Graves often helped out behind the counter, The shop signboard, almost certainly painted by Nancy Nicholson. The Wandering Scholar is looking across fields to the ‘dreaming spires’ – All 206 GRAVESIANA: THE JOURNAL OF THE ROBERT GRAVES SOCIETY Saints spire, St Mary’s, the Radcliffe Camera, Magdalen Tower. It was found in woodland near Dingle Cottage, and had apparently been made into part of a children’s playhouse. The image is painted on two metal sheets mounted back-to-back in a wooden frame; on the top are two stout eyes from which to suspend it. Expertise must have gone into the choice of paints, which survived exposure to the elements for some years. One side is brighter but has three small craters, as if hit by air-gun pellets; the other side is more scratched and pitted. (Photo: Philip Stewart.) but it was not his enterprise. It occupied a wooden shed, which soon had to be expanded to make room for more stock. At first the grocery did very well, thanks largely to curious visitors, who came up from Oxford in the hope of buying cheese from the hands of the poet. However, business soon slackened and they began to lose money. They tried to get the shop taken over by an Oxford firm, but Mrs Masefield persuaded the owner of the land not to agree, as she felt it would lower the tone of the neighbourhood. -

Senatorial Bias in the Portrayal of Gaius Caligula

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PDXScholar Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2020 Apr 27th, 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM Senatorial Bias in the Portrayal of Gaius Caligula Haley E. Stark Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Stark, Haley E., "Senatorial Bias in the Portrayal of Gaius Caligula" (2020). Young Historians Conference. 14. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2020/papers/14 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Senatorial Bias in the Portrayal of Gaius Caligula Haley Stark Honors Western Civilizations Humanities January 22, 2020 1 The name “Caligula” is synonymous with the most egregious excesses of the Roman Empire. Known for his extravagant spending, vicious temper, and outright madness, Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, better known as Caligula, is seen as more monster than man. Despite his horrible reputation, many of Caligula’s actions enriched the lives of the public and are often ignored by historians in lieu of his infamous violence, wrought out of a lifetime of fear living under a hostile Senate and his cruel uncle Tiberius. Even his most extreme acts were not without reason in the cutthroat environment of the early Roman Empire, and ancient authors who made claims of incest and insanity against him exaggerated and fabricated events of his life as a means to slander Caligula and support the senatorial elite’s biases against him. -

'A Poet You Shall Be, My Son': Robert Graves and Dylan Thomas

‘A poet you shall be, my son’: Robert Graves and Dylan Thomas Nancy Rosenfeld Robert Graves lived during the modernist period and often wrote on themes associated with modernism. As co-author, together with Laura Riding, of A Survey of Modernist Poetry, Graves commented widely on contemporary poets and their creations. In this collaborative work Riding and Graves differentiate between ‘modern-ness’, that is, ‘keeping up in poetry with the pace of civilization and intellectual history’, and ‘modernism’.1 Whatever the period in which he lives, an excellent poet is, according to Riding and Graves, ‘something more than a mere servant and interpreter of civilization’. He is, rather, ‘a new and original individual’.2 Modernism, an attack on so-called bourgeois values and thought, was rooted in the nineteenth century, but came to the forefront in the aftermath of the Great War. The Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism provides a useful definition: ‘it is associated with experimentation with traditional genres and styles, and a conception of the artist as creator rather than preserver of culture’, as well as being ‘unconventional, often formally complex and thematically apocalyptic'.3 Indeed, the above view of the artist as ‘'creator rather than preserver of culture’' recalls Riding’s and Graves’s definition of the first-rate poet as ‘a new and original individual’. Although in time the term Neo- (or New) Romanticism came to be applied to the writings of poets such as Dylan Thomas, conventional scholarly wisdom is not