Refugees, Asylum Seekers & Immigration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Place Like Home for Falcons

OOFFICIALFFICIAL PPUBLICATIONUBLICATION OOFF TTHEHE WWAFLAFL RROUNDOUND 1 MMARCHARCH 116,6, 22013013 $$3.003.00 AWARDS NNoo pplacelace llikeike hhomeome fforor FFalconsalcons TTweetsweets ooff tthehe WWeekeek WWAA FFootballootball HHallall ooff FFameame The Lions take top marks, so does our insurance. We’re proud to be Major Sponsor of the Subiaco Lions. And even prouder that our car and home policies are competitively priced. Better still, we’ll help you find the cover that’s right for you. To find out what we’ve made possible, call QBE today on 133 723. Call us for a PDS to decide if a product is right for you. QBE Insurance (Australia) Limited ABN 78 003 191 035, AFSL 239545. Every Week 6 Awards 7 Tipping 25-27 WAFC news 28 Country Football 29 Community Football 30 Club notes 31 WAFL Stats 33 Ladders & results 34 Fixtures Game time 13 Previews 14-15 Claremont v South Fremantle 16-17 East Fremantle v Swan Districts 20-21 Perth v Peel 22-23 West Perth v East Perth Features 4-6 No place like home 8 Collectables 9 Entertainment 10-12 WA Football Hall of Fame 18-19 East Fremantle team poster 24 WAFL club gains and losses 32 Foxtel Cup CONTENTS3 By Ross Lewis 4 @r_lewis_thewest Publisher This publication is proudly produced for the WA Football Commission by Media Tonic. Phone 9388 7844 Fax 9388 7866 Sales [email protected] No place like Editor Tracey Lewis Email [email protected] @traceylewis5 Contributing writers Ross Lewis, Andrea Damonse, Sean Cowan. Photography home for Falcons Andrew Ritchie, William Crabb & Paul Litherland Design/Typesetting Jacqueline Holland - Visible Ink Graphics For almost 20 years West Perth has been living in Printing Quality Press. -

East Fremantle Football Club 2 017 Annual Report

EAST FREMANTLE FOOTBALL CLUB 2 017 ANNUAL REPORT Lynn Medallist COLTS PREMIERS 2017 Jayden Schofield MELVILLE Hilton Hilton EVERY DAY 8AM - 10PM EVERY DAY 8AM - 10PM Working collaboratively with you and your GP toWorking improve collaboratively your health with you and your GP to improve your health Free Express Delivery on weekdays* Free Express Delivery on weekdays* Sleep apnoea screening and management Sleep apnoea screening and management Diabetes management and NDSS supplies Diabetes management and NDSS supplies Private pharmacist consultations Private pharmacist consultations Quick Check health assessments Quick Check health assessments Medication reviews Medication reviews Pain Pain management management *Conditions *Conditions apply apply 300 300South South St, St,Hilton Hilton 08 933708 9337 1434 1434 [email protected]@pharmacy777.com.au ENV302_East Fremantle Football Club's Annual Report for 2017_ART.pdf 1 28/09/2017 2:33 pm MRI | CT | PET | Ultrasound | X-Ray | NucMed | Dental C M Specialists in Y CM Sports Imaging MY Envision is the preferred CY medical imaging provider for leading sports practitioners CMY and professional athletes. K • Personal service • Short Ultrasound waiting times • State-of-the-art scanners, including Perth’s first Siemens 3T Skyra MRI Experience & innovation. State-of-the-art equipment. Personalised care. 178-190 Cambridge Street | Wembley | 6382 3888 | envisionmi.com.au Published by Perth Advertising Services. Phone: 9375 1922. Fax: 9275 2955. Contents Board, Administration, Patrons ....................................... -

EX-VFL Players Now In

CCANNONSannons remainREMAIN inIN topTOP fourFOUR AFL VICTORIA VFL ROUND 8, TAC CUP ROUND 7 MAY 12-13, 2012 $3 SandrinGHAM rise to THird EDITORIAL More AFL debuts Another Peter Jackson VFL draftee debuted in the AFL on the weekend, continuing to highlight the great pathway to the highest competition. AHMED Saad, last year’s Peter Jackson VFL and 42 of it offers players the opportunity winner of the Fothergill those players have played at each and every week to play Round Medal for the most least one AFL match against AFL listed players. promising young player in From the 16 VFL players Interestingly, a total of 28 the Peter Jackson VFL, made selected at last year’s NAB former VFL players last week his AFL debut for St Kilda AFL Drafts, six – Saad, Jarrod played for an AFL Club and last weekend. Boumann (Box Hill Hawks/ that included some of the Saad, a youngster of Egyptian Hawthorn), Tim Mohr (Casey game’s biggest names – Sam heritage, is a great football Scorpions/Greater Western Mitchell, Nick Maxwell and story. He virtually ‘invited’ Sydney), Orren Stephenson Matthew Boyd – the latter two himself to training for the (North Ballarat/Geelong), Tory current AFL Club captains then Northern Bullants and Dickson (Bendigo/Western and the former a premiership on occasions could not Bulldogs) and James Magner captain. get a game in the club’s (Sandringham/Melbourne) – Just like Saad, at some point Development League team. have already made their AFL early in their careers they all Throughout those testing times, debut in 2012. played in the Development Saad’s commitment never That number is another League, which, again, wavered as he strove to get personal best for the Peter underlines the importance of the best out of himself; working Jackson VFL, which in the late this competition’s role in the his way from the Development 1990s sometimes struggled talent pathway. -

Rookies Lesson 8 – Many Players, One Team

ROOKIES LESSON 8 – MANY PLAYERS, ONE TEAM STUDENT WORKSHEET 8.1 Can I Kick It? – Player Data You and your partner(s) are going to investigate 20 players in the AFL. The players you investigate must come from the list provided below and from no more than three teams. Adelaide Crows Brisbane Lions Carlton Collingwood Brodie Smith Mitchell Golby Jayden Foster Michael Manteit Nathan Van Berlo Pearce Hanley Blaine Boekhorst Tim Broomhead Ryan Harwood Bradley Walsh Steele Sidebottom Ryan Lester Sam Docherty Marley Williams Matthew Leuenberger Zach Tuohy Ben Hudson Dayne Zorko Ciaran Byrne Nathan Freeman Jordan Bourke Ciaran Sheehan Essendon Fremantle Geelong Cats Gold Coast SUNS Kyle Langford Zachary Clarke Jordan Schroder Touk Miller James Gwilt Garrick Ibbotson Billie Smedts Greg Broughton David Zaharakis Chris Mayne Jarrad Jansen Adam Saad Mark Baguley Tendai Mzungu Nick Malceski Alex Silvagni Tom Nicholls Hayden Crozier Danny Stanley Anthony Morabito Aaron Hall Clancee Pearce Daniel Gorringe David Swallow Greater Western Sydney Hawthorn Melbourne North Melbourne Phil Davis Josh Gibson Christian Petracca Daniel Neilson Aidan Corr David Hale Heritier Lumumba Sam Durdin Lachie Whitfield Alex Woodard Max Gawn Liam Anthony Rhys Palmer Sam Mitchell Jack Watts Majak Daw Stephen Coniglio Paul Puoplo Christian Salem Michael Firrito Liam Shiels Andrew Swallow Shem-Kalvin Tatupu Robin Nahas Kurt Heatherly Page 1 of 9 ROOKIES LESSON 8 – MANY PLAYERS, ONE TEAM STUDENT WORKSHEET 8.1 Can I Kick It? – Player Data Port Adelaide Richmond St Kilda Sydney -

Easter Weekend Game Previews West Perth Poster

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WAFL ROUND 5 APRIL 18, 2014 $3.00 AAdvanceddvanced pplanninglanning ggivesives SSharksharks bbiteite EEasteraster wweekendeekend ggameame ppreviewsreviews WWestest PPertherth pposteroster What’s your car worth? TRADING IN YOUR CAR IS EASY AS 1,2,3! Right now AHG Dealerships will give you a great price for your trade-in! With low finance rates available, you could be driving a newer car and possibly paying lower finance repayments! To find out what your car is worth go to ahg.com.au Proud Supporters of the Royals! Every Week 7 Tipping 7 Tweets of the Week 10 Club Notes 23-25 WAFC 28 Stats 29 Ladders & Results 30 Fixtures Features 8 Collectables 9 Entertainment 16-17 West Perth poster Game time 11 Previews 12-13 Peel v East Fremantle 14-15 Subiaco v East Perth 18-19 West Perth v South Fremantle 20-21 Perth v Swan Districts 22 Sydney v Fremantle 22 West Coast v Port Adelaide 3 4 ADVANCEDggivesives SSharksh aPLrksA early season bite Publisher This publication is proudly produced for the WA Football Commission by East Fremantle was one of the teams hardest hit finals. Combined they had played a career total of Media Tonic. when it came to losing playing stocks following the 148 games for the Sharks. So far in season 2014, they Phone introduction of the Partnering Model for season have played a total of 10 games for the Thunder. 9388 7844 Fax 9388 7866 Sales 2014. The Sharks also lost retiring Eagles Brad Dick [email protected] Under the new arrangement, all Fremantle listed and Daniel Kerr who played 10 and three games Editor players have been located at Peel Thunder and all respectively for the Sharks. -

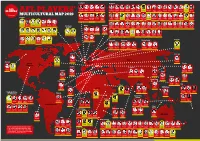

Afl Players' Multicultural Map 2019

Scotland England Aiden Bonar Aidan Corr Sam Docherty Paul Hunter Kirsten McLeod Oscar Allen Charlie Ballard Nicola Barr Kieren Briggs Riley Bonner Tim Callum Brown Stephanie Cain Stephen Callum Phil Davis Liam Dawson Tory Dickson Sam Draper Jade Ellenger Alicia Eva GWS GIANTS GWS GIANTS CARLTON ADELAIDE WESTERN WEST COAST GOLD COAST GWS GIANTS GWS GIANTS PORT Broomhead GWS GIANTS FREMANTLE Coniglio Coleman-Jones GWS GIANTS BRISBANE WESTERN ESSENDON BRISBANE GWS GIANTS AFL PLAYERS’ BULLDOGS ADELAIDE COLLINGWOOD GWS GIANTS RICHMOND BULLDOGS MULTICULTURAL MAP 2019 Ireland Brodie Smith Sam William Walker Aaron Young Cameron Zac Foot Billy Frampton Sabrina Ryan Hugh Goddard Damon Greaves Brianna Green Pearce Hanley Anne Hatchard Sam Hayes Jacob Heron Dana Hooker Dan Houston Nathan Hrovat Connor Idun Peter Ladhams ADELAIDE Switkowski NORTH GOLD COAST Zurhaar SYDNEY PORT Frederick Garthwaite CARLTON HAWTHORN FREMANTLE GOLD COAST ADELAIDE PORT GOLD COAST FREMANTLE PORT NORTH GWS GIANTS PORT FREMANTLE MELBOURNE NORTH ADELAIDE BRISBANE RICHMOND ADELAIDE ADELAIDE MELBOURNE ADELAIDE MELBOURNE Yvonne Bonner Callum Brown Ailish Conor Glass Pearce Hanley Nathan Jones Zak Jones GWS GIANTS GWS GIANTS Considine HAWTHORN GOLD COAST MELBOURNE SYDNEY Wales Sweden ADELAIDE Northern Mitchell Lewis Ryan Lester Chris Mayne Jarrad McVeigh Rhiannon Hayley Miller Dylan Moore Kurt Mutimer Connor Nutting Brodie Riach Josh Rotham Shane Savage Jessica Philipa Seth William Brodie Smith HAWTHORN BRISBANE COLLINGWOOD SYDNEY Metcalfe FREMANTLE HAWTHORN WEST COAST GOLD COAST -

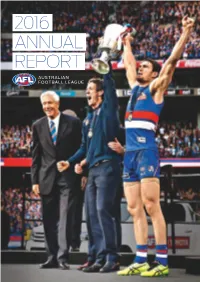

2016 Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 120TH ANNUAL REPORT 2016 4 2016 Highlights 16 Chairman’s Report 30 CEO’s Report 42 AFL Clubs & Operations 52 Football Operations 64 Commercial Operations 78 NAB AFL Women’s 86 Game & Market Development 103 Around The Regions 106 AFL in Community 112 Legal & Integrity 120 AFL Media 126 Awards, Results & Farewells 139 Obituaries 142 Financial Report 148 Concise Financial Report Western Bulldogs coach Cover: The wait is over ... Luke Beveridge presents Luke Beveridge (obscured), his Jock McHale Medal Robert Murphy and captain to injured skipper Robert Easton Wood raise the Murphy, a touching premiership cup, which was gesture that earned him a presented by club legend Spirit of Australia award. John Schultz (left). 99,981 The attendance at the 2016 Toyota AFL Grand Final. 4,121,368 The average national audience for the 2016 Toyota AFL Grand Final on the Seven Network which made the Grand Final the most watched program of any kind on Australian television in 2016. This total was made up of a five mainland capital city metropolitan average audience of 3,070,496 and an average audience of 1,050,872 throughout regional Australia. 18,368,305 The gross cumulative television audience on the Seven Network and Fox Footy for the 2016 Toyota AFL Finals Series which was the highest gross cumulative audience for a finals series in the history of the AFL/VFL. The Bulldogs’ 62-year premiership drought came to an end in an enthralling Grand Final, much to the delight of young champion Marcus Bontempelli and delirious 4 Dogs supporters. -

WA Women's Football League Grand Finals

OOFFICIALFFICIAL PPUBLICATIONUBLICATION OOFF TTHEHE WWAFLAFL RROUNDOUND 2233 AAUGUSTUGUST 224,4, 22013013 $$3.003.00 WWAA WWomen’somen’s FFootballootball LLeagueeague GGrandrand FFinalsinals GGameame ppreviewsreviews EEntertainmentntertainment The Lions take top marks, so does our insurance. We’re proud to be Major Sponsor of the Subiaco Lions. And even prouder that our car and home policies are competitively priced. Better still, we’ll help you find the cover that’s right for you. To find out what we’ve made possible, call QBE today on 133 723. Call us for a PDS to decide if a product is right for you. QBE Insurance (Australia) Limited ABN 78 003 191 035, AFSL 239545. Every Week 7 Tipping 7 Tweets of the Week 25 Country Football 26 Amateur Football 27 Club calendar 28 WAFL Stats 29 Ladders & results 30 Fixtures Game time 9 Collingwood v West Coast 9 Fremantle v Port Adelaide 13 Previews 14-15 Perth v Claremont 16-17 South Fremantle v East Perth 18-19 Subiaco v Peel 20-21 Swan Districts v East Fremantle 22-24 Women’s Football League Grand Finals Features 4-5 Five keys to the finals 6 Awards 8 Entertainment 10-11 Collectables CONTENTS3 By Ross Lewis 4 @r_lewis_thewest kkeyseys ttoo Publisher This publication is proudly produced for the WA Football Commission by Media Tonic. Phone 9388 7844 Fax 9388 7866 Sales ccelebrationelebration [email protected] Editor Tracey Lewis Email [email protected] The time of year has come when you can count the So for five teams it has come down to five weeks. -

2017 Premiers CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 121ST ANNUAL REPORT 2017

Australian Football League Annual Report 2017 Premiers CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 121ST ANNUAL REPORT 2017 4 2017 Highlights 16 Chairman’s Report 26 CEO’s Report 36 Strong Clubs 44 Spectacular Game 68 Revenue/Investment 80 Financial Report 96 Community Football 124 Growth/Fans 138 People 144 Awards, Results & Farewells Cover: The 37-year wait is over for Richmond as coach Damien Hardwick and captain Trent Cotchin raise the premiership cup; co-captains Chelsea Randall and Erin Phillips with coach Bec Goddard after the Adelaide Crows’ historic NAB AFLW Grand Final win. Back Cover: Richmond star Jack Riewoldt joining US Jubilant Richmond band The Killers on fans erupt around the stage at the Grand MCG at the final siren Final Premiership as the Tigers clinch Party was music their first premiership to the ears of since 1980. Tiger fans. 100,021 The attendance at the 2017 Toyota AFL Grand Final 3,562,254 The average national audience on the Seven Network for the 2017 Toyota AFL Grand Final, which was the most watched program of any kind on Australian television in 2017. This was made up by an audience of 2,714,870 in the five mainland capital cities and an audience in regional Australia of 847,384. 16,904,867 The gross cumulative audience on the Seven Network and Fox Footy Channel for the 2017 Toyota AFL Finals Series. Richmond players celebrate after defeating the Adelaide Crows in the 2017 Toyota AFL Grand Final, 4 breaking a 37-year premiership drought. 6,732,601 The total attendance for the 2017 Toyota AFL Premiership Season which was a record, beating the previous mark of 6,525,071 set in 2011. -

2019 Annual Report 2019 Premiers

2019 ANNUAL REPORT2019 ANNUAL 2019 ANNUAL 2019 REPORT PREMIERS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE AUSTRALIAN 2019 AFL AR Cover_d5.indd 3 19/2/20 13:54 CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 123RD ANNUAL REPORT 2019 4 2019 Highlights 14 Chairman’s Report 24 CEO’s Report 34 Football Operations 44 AFL Women’s 54 Broadcasting 60 Game Development, Legal & Integrity 84 Commercial Operations 100 Growth, Digital & Audience 108 Strategy 114 People & Culture 118 Inclusion & Social Policy 124 Corporate Affairs 130 Infrastructure 134 Awards, Results & Farewells 154 Financial Report The MCG was filled Cover: The jubilant Back Cover: Tayla Harris to capacity when the Richmond and displays her perfect kicking Giants, playing in their Adelaide Crows teams style, an image that will go first Grand Final, did celebrate their 2019 down as a pivotal moment battle with the Tigers. premiership triumphs. in the women’s game. 2019 AFL AR Cover_d5.indd 6 19/2/20 13:54 2019 AFL AR Cover_d5.indd 9 19/2/20 13:54 100,014 The attendance at the 2019 Toyota AFL Grand Final 2,938,670 Television audience for the Toyota AFL Grand Final. 6,951,304 Record home and away attendance. Five-goal hero Jack Riewoldt whips adoring Tiger fans into a frenzy after Richmond’s emphatic 4 Grand Final win over the GWS Giants. 4-13_2019 Annual Report_Highlights_FA.indd 4 25/2/20 14:24 4-13_2019 Annual Report_Highlights_FA.indd 5 25/2/20 14:24 1,057,572 Record total club membership of 1,057,572, compared with 1,008,494 in 2018 35,108 Average home and away match attendance of 35,108, compared with 34,822 in 2018. -

Beyond the Boats: Building an Asylum and Refugee Policy for the Long Term Long the for Policy Refugee and Asylum an Building Boats: the Beyond

Beyond the boats: building an asylum and refugee policy for the long term Australia21 is a not for profit research company, founded Established in the Faculty of Law at the University of NSW in 2001 that is not affiliated with any political party or in 2013, it seeks to produce high-quality research feeding interest group. We bring together leading thinkers from into public policy and legislative reform. all sectors of the Australian community to explore the The Centre for Policy Development is an independent and evidence and develop new frameworks for understanding non-partisan policy institute. Our focus is developing and dealing with some of the major challenges facing long-term policy ideas that can outlast political cycles the nation. We make the results of our investigations and Beyond the boats: building an asylum and enhance the lives of current and future generations. research widely available to policy developers, industry, CPD’s core model is threefold: we create viable ideas media and the public. and refugee policy for the long term from rigorous, cross-disciplinary research at home and The Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International abroad. We connect experts and stakeholders to develop Refugee Law at UNSW is the world’s first academic these ideas into practical policy proposals. We then work Report following high-level roundtable research centre dedicated to the study of international to convince government, business and civil society of the refugee law and policy. merits of implementation. Bob Douglas, Claire Higgins, Arja Keski-Nummi, Jane McAdam and Travers McLeod Report roundtable high-level following 51883 Aus21 Beyond the Boats Report - Cover_FA2.indd 1 29/10/2014 7:20 pm Widyan Al Ubudy Aliir Aliir Widyan Al Ubudy is a broadcast journalist with Special Aliir Aliir is a professional footballer in the Australian Football Broadcasting Service (SBS) News and was formerly radio host League (AFL). -

Farewell to Footy's Loyal Servant

OOFFICIALFFICIAL PPUBLICATIONUBLICATION OOFF TTHEHE WWAFLAFL RROUNDOUND 1122 JJUNEUNE 88,, 22013013 $$3.003.00 FFarewellarewell ttoo ffooty’sooty’s lloyaloyal sservantervant GGameame ppreviewsreviews TTweetsweets ooff tthehe WWeekeek The Lions take top marks, so does our insurance. We’re proud to be Major Sponsor of the Subiaco Lions. And even prouder that our car and home policies are competitively priced. Better still, we’ll help you find the cover that’s right for you. To find out what we’ve made possible, call QBE today on 133 723. Call us for a PDS to decide if a product is right for you. QBE Insurance (Australia) Limited ABN 78 003 191 035, AFSL 239545. Game time 9 Previews 10-11 East Fremantle v Peel 12-13 West Perth v Claremont 14-15 Subiaco v South Fremantle 17 St Kilda v West Coast 17 Fremantle stats Every Week 7 Tipping 7 Tweets of the Week 18-20 WAFC news Features 21 Country Football 22 Amateur Football 4-5 Farewell to a loyal footy servant 23 Club calendar 6 Awards 24 WAFL stats 8 Collectables 25 Ladders & results 16 Mark McGough Q & A 26 Fixtures CONTENTS3 By Ross Lewis 4 @r_lewis_thewest FFarewellarewell Publisher This publication is proudly produced for the WA Football Commission by Media Tonic. to footy’s loyal servant Phone 9388 7844 Fax 9388 7866 Sales [email protected] Five decades of dedication to Australian Football into administration for over 30 years, it is part of your Editor will soon come to an end. DNA. Tracey Lewis Email Grant Dorrington has been asscoaited with The wonderful people, especially the passionate [email protected] the great Australian game his entire adult life, volunteers who you interact with along this footy @traceylewis5 serving as player, coach, selector, commentator and life journey make it extra special.