Colliers and Christianity: Religion in the Coalmining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Profile – Ynyswen, Treorchy and Cwmparc

Community Profile – Ynyswen, Treorchy and Cwmparc Version 5 – will be updated and reviewed next on 29.05.20 Treorchy is a town and electoral ward in the county borough of Rhondda Cynon Taf in the Rhondda Fawr valley. Treorchy is one of the 16 communities that make up the Rhondda. Treorchy is bordered by the villages of Cwmparc and Ynyswen which are included within the profile. The population is 7,694, 4,404 of which are working age. Treorchy has a thriving high street with many shops and cafes and is in the running as one of the 3 Welsh finalists for Highs Street of the Year award. There are 2 large supermarkets and an Treorchy High Street industrial estate providing local employment. There is also a High school with sixth form Cwmparc Community Centre opportunities for young people in the area Cwmparc is a village and district of the community of Treorchy, 0.8 miles from Treorchy. It is more of a residential area, however St Georges Church Hall located in Cwmparc offers a variety of activities for the community, including Yoga, playgroup and history classes. Ynyswen is a village in the community of Treorchy, 0.6 miles north of Treorchy. It consists mostly of housing but has an industrial estate which was once the site of the Burberry’s factory, one shop and the Forest View Medical Centre. Although there are no petrol stations in the Treorchy area, transport is relatively good throughout the valley. However, there is no Sunday bus service in Cwmparc. Treorchy has a large population of young people and although there are opportunities to engage with sport activities it is evident that there are fewer affordable activities for young women to engage in. -

Maerdy, Ferndale and Blaenllechau

Community Profile – Maerdy, Ferndale and Blaenllechau Version 6 – will be updated and reviewed next on 29.05.20 Maerdy Miners Memorial to commemorate the mining history in the Rhondda is Ferndale high street. situated alongside the A4233 in Maerdy on the way to Aberdare Ferndale is a small town in the Rhondda Fach valley. Its neighboring villages include Maerdy and Blaenllechau. Ferndale is 2.1 miles from Maerdy. It is situated at the top at the Rhondda Fach valley, 8 miles from Pontypridd and 20 miles from Cardiff. The villages have magnificent scenery. Maerdy was the last deep mine in the Rhondda valley and closed in 1985 but the mine was still used to transport men into the mine for coal to be mined to the surface at Tower Colliery until 1990. The population of the area is 7,255 of this 21% is aged over 65 years of age, 18% are aged under 14 and 61% aged 35-50. Most of the population is of working age. 30% of people aged between 16-74 are in full time employment in Maerdy and Ferndale compared with 36% across Wales. 40% of people have no qualifications in Maerdy & Ferndale compared with 26% across Wales (Census, 2011). There is a variety of community facilities offering a variety of activities for all ages. There are local community buildings that people access for activities. These are the Maerdy hub and the Arts Factory. Both centre’s offer job clubs, Citizen’s Advice Bureau (CAB) and signposting. There is a sports centre offering football, netball rugby, Pen y Cymoedd Community Profile – Maerdy and Ferndale/V6/02.09.2019 basketball, tennis and a gym. -

YSTRADOWEN YSTRADYFODWG, &C

62G YSTRADOWEN YSTRADYFODWG, &c. Thomas David, carpenter ThomR.!I William, farmer Thomas Edward, shoemaker Williams Philemon, f&rmer Thomas William, farmer Y BTRADOWEN, a parish and viiJage in the Bridgend and Cow bridge union and county court district, 3 miles from Cowbridge, and in the diocese and archdeaconry of Llandaff and deanery of Lower Llanda.ff, eastern division. The parish contains 1,003 acres; the rateable value is £1,100. Mrs. Ricketts, of Dorton House, Bucks, is lady of the manor, and, with the Spearman family, owns the soil. The line of railway to Cowbridge intersects the parish. The only place of worship is the parish church. The Rev. David Jones is the incumbent. PosTAL REGULATIONS. Letters are received through Cowbridge, which is the nearest money-order office and its post town. Owen Daniel, Esq. Matthews William, farmer COMMERCIAL. Morgan Enoch, farmer Da.vid Jacob, blacksmith Samuel John, wheelwright Davies Da.vid H., innkeeper Thomas William, farmer Evans David, farmer Williams Miles, farmer Harry Howell, farmer Williams Rees, builder Howe John, farmer Williams Thomas, farmer • • YsTRADYFODWG: WITH THE HAMLET OF THE RIGHOS AND THE VILLAGE OF TREHERBERT. Y STRADYFODWG is a large parish, situated in the Rhondda. Valley, 10 miles from Pon typridd, and is connected to that place by a branch of the Taff Vale Railway. It is in the Pontypridd union and county court district, diocese and archdeaconry of Landaff, and deanery of Upper Llandaff, northern division. The area of the parish, including the hamlet of th~ Righos, is estimated at 25,000 statute acres, the greater portion of which is moun tain waste, serving ouly for the feeding of sheep, but immensely rich in mineral wealth, and will become one of the principal coal producing dis tricts of South Wales. -

The London Gazette, 19 July, 1929. 4837

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 19 JULY, 1929. 4837 NEEDHAM; George Frederick, trading as FRliX PUGH, William, 58, Wern-street, Clydach Vale, . ' NEEDHAM, residing and trading at 166, Glamorgan. GROCER. Alfred-street South, Nottingham. WRING- Couri^PQNTYPRIDD, YSTRADYFODWG and ING and MANGLING MACHINE DEALER PORTH. ." and REPAIRER. No. of Matter—38 of 1928. Court—NOTTINGHAM. Trustee's Name, Address and Description— No. of Matter—51 of 1927. 0*ven, Ellis, 34, Park-place, Cardiff, Official - Trustee's Name, Address and Description— Receiver. .West Leslie Arthur, 22, Regent-street, Park- Date of Release—July 1, 1929. row, Nottingham, Official Receiver. Date of Release—July 8, 1929. THOMAS, Rupert Edwin, .residing at 31,-Syca- more-street, Rhydfelan, Pontypridd, Glamor- NIOHOL, Oscar residing at 23, Charnwood-grove, gan, and carrying on business at 84A, Taff- West Bridgford, Nottinghamshire, and carry- street, Pontypridd aforesaid. HATTER and ing on business at SA, Pepper-street, Notting- HOSIER. ham. GENERAL DEALER. Court^PONTYPRIDD, YSTRADYFODWG and Court—NOTTINGHAM. PORTH. No. of Matter—31 of 1928. No, of Matter—37 of 1928. - Trustee's Name, Address and Description— Trustee's 'Name, Address and. Description— West Leslie Arthur, 22, Regent-street, Park- Owen, Ellis, 34, Park-place, Cardiff, Official row, Nottingham, Official Receiver. Receiver. Date of Release—July 8, 1929. Date of Release—July 1, 1929. DAVID, William (trading as W. DAVID & THOMAS, 'Thomas' Herbert, ' residing at 25, SONS), 210, Ystrad-road, Pentre, in the 'Ebeneze'r - street, Rhydfelen, Glamorgan. parish of Rhondda, Glamorgan. PLUMBER, CREDIT DRAPER, OUTFITTER and BOOT GAS and HOT WATER FITTER. and SHOE DEALER. Court—PONTYPRIDD, YSTRADYFODWG and Courl^PONTYPRIDD, YSTRADYFODWG and PORTH. -

Rhondda Cynon Taf Christmas 2019 & New Year Services 2020

Rhondda Cynon Taf Christmas 2019 & New Year Services 2020 Christmas Christmas Service Days of Sunday Monday Boxing Day Friday Saturday Sunday Monday New Year's Eve New Year's Day Thursday Operators Route Eve Day number Operation 22 / 12 / 19 23 / 12 / 19 26 / 12 / 19 27 / 12 / 19 28 / 12 / 19 29 / 12 / 19 30 / 12 / 19 31 / 12 / 19 01 / 01 / 20 02 / 01 / 20 24 / 12 / 19 25 / 12 / 19 School School School Mon to Sat Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 1 Aberdare - Abernant No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Service Service Service Service Service Service Service School School School Mon to Sat Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 2 Aberdare - Tŷ Fry No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Service Service Service Service Service Service Service Early Finish Globe Mon to Sat Penrhiwceiber - Cefn Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal 3 No Service No Service No Service No Service (see No Service Coaches (Daytime) Pennar Service Service Service Service Service Service summary) School School School Mon to Sat Aberdare - Llwydcoed - Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 6 No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Merthyr Tydfil Service Service Service Service Service Service Service Harris Mon to Sat Normal Normal Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Normal 7 Pontypridd - Blackwood No Service No Service No Service No Service No Service Coaches (Daytime) Service Service Service -

Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS REPORT AND PROPOSALS COUNTY BOROUGH OF RHONDDA CYNON TAF LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE COUNTY BOROUGH OF RHONDDA CYNON TAF REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. SUMMARY OF PROPOSALS 3. SCOPE AND OBJECT OF THE REVIEW 4. DRAFT PROPOSALS 5. REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO THE DRAFT PROPOSALS 6. ASSESSMENT 7. PROPOSALS 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 9. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT APPENDIX 1 GLOSSARY OF TERMS APPENDIX 2 EXISTING COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP APPENDIX 3 PROPOSED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP APPENDIX 4 MINISTER’S DIRECTIONS AND ADDITIONAL LETTER APPENDIX 5 SUMMARY OF REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO DRAFT PROPOSALS The Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales Caradog House 1-6 St Andrews Place CARDIFF CF10 3BE Tel Number: (029) 2039 5031 Fax Number: (029) 2039 5250 E-mail [email protected] www.lgbc-wales.gov.uk FOREWORD This is our report containing our Final Proposals for Cardiff City and County Council. In January 2009, the Local Government Minister, Dr Brian Gibbons asked this Commission to review the electoral arrangements in each principal local authority in Wales. Dr Gibbons said: “Conducting regular reviews of the electoral arrangements in each Council in Wales is part of the Commission’s remit. The aim is to try and restore a fairly even spread of councillors across the local population. It is not about local government reorganisation. Since the last reviews were conducted new communities have been created in some areas and there have been shifts in population in others. This means that in some areas there is now an imbalance in the number of electors that councillors represent. -

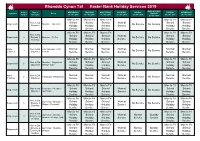

Rhondda Cynon Taf Easter Bank Holiday Services 2019

Rhondda Cynon Taf Easter Bank Holiday Services 2019 BANK HOLIDAY Service Days of WEDNESDAY THURSDAY GOOD FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY Operators Route MONDAY number Operation 17 / 04 / 2019 18 / 04 / 2019 19 / 04 / 2019 20 / 04 / 2019 21 / 04 / 2019 23 / 04 / 2019 24 / 04 / 2019 22 / 04 / 2019 Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat School School School Normal School School Stagecoach 1 Aberdare - Abernant No Service No Service (Daytime) Holiday Holiday Holiday Service Holiday Holiday Service Service Service Service Service Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat School School School Normal School School Stagecoach 2 (Daytime & Aberdare - Tŷ Fry No Service No Service Evening) Holiday Holiday Holiday Service Holiday Holiday Service Service Service Service Service Globe Mon to Sat Penrhiwceiber - Cefn Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal 3 No Service No Service Coaches (Daytime) Pennar Service Service Service Service Service Service Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat Aberdare - Llwydcoed - School School School Normal School School Stagecoach 6 No Service No Service (Daytime) Merthyr Tydfil Holiday Holiday Holiday Service Holiday Holiday Service Service Service Service Service Harris Mon to Sat Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal 7 Pontypridd - Blackwood No Service No Service Coaches (Daytime) Service Service Service Service Service Service Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat Penderyn - Aberdare - School -

Starting School 2018-19 Cover Final.Qxp Layout 1

Starting School 2018-2019 Contents Introduction 2 Information and advice - Contact details..............................................................................................2 Part 1 3 Primary and Secondary Education – General Admission Arrangements A. Choosing a School..........................................................................................................................3 B. Applying for a place ........................................................................................................................4 C.How places are allocated ................................................................................................................5 Part 2 7 Stages of Education Maintained Schools ............................................................................................................................7 Admission Timetable 2018 - 2019 Academic Year ............................................................................14 Admission Policies Voluntary Aided and Controlled (Church) Schools ................................................15 Special Educational Needs ................................................................................................................24 Part 3 26 Appeals Process ..............................................................................................................................26 Part 4 29 Provision of Home to School/College Transport Learner Travel Policy, Information and Arrangements ........................................................................29 -

Tremle Court, Treorchy, Rhondda, Cynon, Taff. CF42 6ST 334,950

Tremle Court, Treorchy, Rhondda, Cynon, Taff. CF42 6ST 334,950 • 3-5 Bedrooms • Detached • 1-3 Reception Rooms • Large Front Garden With Driveway • Landscaped Rear Garden • Garage & Workshop • Ample Parking • One of a Kind • Simply Stunning Ref: PRA10363 Viewing Instructions: Strictly By Appointment Only General Description Simply stunning one of a kind! This beautiful detached house has so much to offer, with 3-5 bedroom (currently 3) 1-3 reception rooms (currently 3) large fitted kitchen, utility space and garage with workshop area, landscaped front and rear gardens. With amazing view of garden and valley, viewing Accommodation Entrance Entrance via upvc double door to front, with upvc double glazed full length window, into hallway. Hallway (9' 4" x 16' 9" Min) or (2.84m x 5.11m Min) (Measurements to stairs): Wood panelling to walls with feature stonework wall, tongue and groove ceiling, tiled flooring, 300mm skirting boards, radiator, power points and access to bedrooms 1 & 3, ground floor W/C , cloakroom and garage. Reception Room 1 (19' 5" x 13' 3") or (5.92m x 4.04m) 1st Floor. Formally used as a cinema room, with amazing views, 2 floor length upvc double glazed floor length picture windows to front, upvc double glazed picture window to side and further upvc double glazed window to side. Plastered walls, wood ceiling, solid wood flooring, 300mm skirting boards, radiator and power points. Reception Room 2 (16' 7" x 11' 11") or (5.05m x 3.64m) 1st Floor. Upvc double glazed french doors to side accessing veranda leading to rear garden, plastered walls and ceiling, parquet flooring, 300mm skirting boards stone fireplace with log burner, radiator and power points. -

Player Registration Football Association of Wales

Player Registration TRANSFER Monday, 26 September, 2016 Football Association Of Wales Active Name ID DOB Player Status Transfer From To Date ANSTEE Cory S 548661 31/01/1997 Non-Contract 09/09/2016 Stanleytown AFC Gelli Hibernia FC BATEMAN Calum C 555228 21/11/1995 Non-Contract 14/09/2016 Caerau Ely FC Cardiff Hibernian FC BEDDIS Joshua P 536096 18/02/1995 Non-Contract 15/09/2016 AFC Whitchurch Ely Rangers FC BEESTY Connor J 657381 17/12/1997 Non-Contract 09/09/2016 Four Crosses FC Llansantffraid Village FC BELL Daniel P 557405 24/09/1993 Non-Contract 09/09/2016 Porthmadog FC Nantlle Vale FC BENNETT Matthew J 469751 17/02/1989 Non-Contract 16/09/2016 FC Queens Park Offa Athletic BIRDSEY Matthew 554546 05/11/1995 Non-Contract 15/09/2016 Briton Ferry Llansawel Bryncoch FC FC BONIFACIO Christopher 702409 20/12/2004 Non-Contract 09/09/2016 Calsonic Kansei Junior Seaside Junior AFC (<18) FC BONSER Greg 671312 21/01/1987 Non-Contract 09/09/2016 The Baglan Pentre Rovers FC BOSWELL Wayne D 482142 28/08/1983 Non-Contract 10/09/2016 Pennar Robins AFC Monkton Swifts BOWEN Darren S 491110 12/07/1970 Non-Contract 09/09/2016 Tata Steel FC Margam Youth Club BRACE Andrew J 581520 06/03/1976 Non-Contract 09/09/2016 Pennar Robins AFC Lamphey AFC BRADY Ciaran A 670461 01/05/1991 Non-Contract 16/09/2016 Rhyl Rovers Rhyl Athletic BRODY MILES Luke 477584 05/04/1989 Non-Contract 09/09/2016 Cardiff Airport Masons Moving Group FC BROWN Corey C 682983 25/02/2004 Non-Contract 15/09/2016 Llangyfelach Colts Prescelli Ragged/Penlan (<18) Junior FC Junior FC CASE Myles -

Railway and Canal Historical Society Early Railway Group

RAILWAY AND CANAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY EARLY RAILWAY GROUP Occasional Paper 251 BENJAMIN HALL’S TRAMROADS AND THE PROMOTION OF CHAPMAN’S LOCOMOTIVE PATENT Stephen Rowson, with comment from Andy Guy Stephen Rowson writes - Some year ago I had access to some correspondence originally in the Llanover Estate papers and made this note from within a letter by Benjamin Hall to his agent John Llewellin, dated 7 March 1815: Chapman the Engineer called on me today. He says one of their Engines will cost about £400 & 30 G[uinea]s per year for his Patent. He gave a bad account of the Collieries at Newcastle, that they do not clear 5 per cent. My original thoughts were of Chapman looking for business by hawking a working model of his locomotive around the tramroads of south Wales until I realised that Hall wrote the letter from London. So one assumes the meeting with William Chapman had taken place in the city rather than at Hall’s residence in Monmouthshire. No evidence has been found that any locomotive ran on Hall’s Road until many years later after it had been converted from a horse-reliant tramroad. Did any of Chapman’s locomotives work on south Wales’ tramroads? __________________________________ Andy Guy comments – This is a most interesting discovery which raises a number of issues. In 1801, Benjamin Hall, M.P. (1778-1817) married Charlotte, daughter of the owner of Cyfarthfa ironworks, Richard Crawshay, and was to gain very considerable industrial interests from his father- in-law.1 Hall’s agent, John Llewellin, is now better known now for his association with the Trevithick design for the Tram Engine, the earliest surviving image of a railway locomotive.2 1 Benjamin Hall was the son of Dr Benjamin Hall (1742–1825) Chancellor of the diocese of Llandaff, and father of Sir Benjamin Hall (1802-1867), industrialist and politician, supposedly the origin of the nickname ‘Big Ben’ for Parliament’s clock tower (his father was known as ‘Slender Ben’ in Westminster). -

The Governing Body of the Church in Wales Corff Llywodraethol Yr Eglwys Yng Nghymru

For Information THE GOVERNING BODY OF THE CHURCH IN WALES CORFF LLYWODRAETHOL YR EGLWYS YNG NGHYMRU REPORT OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE TO THE GOVERNING BODY APRIL 2016 Members of the Governing Body may welcome brief background information on the individuals who are the subject of the recommendations in the Report and/or have been appointed by the Standing Committee to represent the Church in Wales. The Reverend Canon Joanna Penberthy (paragraph 4 and 28) Rector, Llandrindod and Cefnllys with Diserth with Llanyre and Llanfihangel Helygen. The Reverend Dr Ainsley Griffiths (paragraph 4) Chaplain, University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Camarthen Campus, CMD Officer, St Davids, member of the Standing Doctrinal Commission. (NB Dr Griffiths subsequently declined co-option and resigned his membership.) His Honour Judge Andrew Keyser QC (paragraph 4) Member of the Standing Committee, Judge in Cardiff, Deputy Chancellor of Llandaff Diocese, Chair of the Legal Sub-committee, former Deputy President of the Disciplinary Tribunal of the Church in Wales. Governing Body Assessor. Mr Mark Powell QC (paragraph 4 and 29) Chancellor of Monmouth diocese and Deputy President of the Disciplinary Tribunal. Deputy Chair of the Mental Health Tribunal for Wales. Chancellor of the diocese of Birmingham. Solicitor. Miss Sara Burgess (paragraph 4) Contributor to the life of the Parish of Llandaff Cathedral in particular to the Sunday School in which she is a leader. Mr James Tout (paragraph 4) Assistant Subject Director of Science, the Marches Academy, Oswestry. Worship Leader in the diocese of St Asaph for four years. Mrs Elizabeth Thomas (paragraph 5) Elected member of the Governing Body for the diocese of St Davids.