4. Boort and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sea Lake, Hopetoun and Waitchie

Sustainable land management – Sea Lake, Hopetoun and Waitchie David Moody, Jodie Odgers and Bobby Liston, BCG Take home messages • Yield Prophet®- the crop simulation model- is a great tool for assessing crop risk and predicting potential yields. • For renovating overgrazed perennial pasture paddocks, the sowing of cereals is a low risk strategy. • Pasture establishment is extremely difficult in the Mallee in years with limited spring rainfall. • Cereal biomass production may be greater by an order of 10 times than either perennial or leguminous pastures in the first year of establishment. • Best pasture options for a June sowing in terms of biomass in the first year of establishment are either forage brassica or Italian Ryegrass. Background In order to measure and report the potential impact of best management practices for dryland agriculture in the Mallee, six demonstration sites were established in 2005, and a seventh (Sea Lake) was established in 2006. The sites at Sea Lake, Hopetoun, Waitchie, Carwarp, Cowangie, Chinkapook and Walpeup represent a range of land and farming systems. Each site tackles one or more of the various aspects of sustainable agriculture such as salinity management, soil erosion, soil health and nutrient management. BCG is responsible for monitoring and assists with the implementation of best management practices for the Sea Lake, Hopetoun and Waitchie sites. In 2007, all three sites underwent extensive soil sampling and analysis prior to sowing. Throughout the year measurements of the following factors were taken; comparative productivity, water use efficiency, ground water, water use and balance, soil nutrition, soil biota, crop biomass and yields. Sea Lake Demonstration Site The site is 118ha in size and situated 1 km south east of the Sea Lake township. -

Fire Operations Plan

o! <null> SUN - Red CARDROSS Cliffs Tin Tin H LAKES EAST Lake a y t f a i rr e l u d r d M e iv P R e R y n e l a x r Cliffs - Colignan Rd i Red e O R Pitarpunga d Rd ringur Lake s - Me d Cliff Re Macommon Lake Dundomallee Lake d r R e e v o i h R n e a e Dry Iv g id Lake b m ru New r Lake St u urt H M Benanee wy South Wales Lake MS Settlement Rd Tala Merinee Sth Rd HATTAH - RHB to Meridian Rd DUMOSA TRACK Lake Tarpaulin Caringay MS - HKNP - Bend RA NORTH EAST DUMOSA Robinvale Hk Boolca ROB BOUNDARY TRK NORTH block grasslands - BUMBANG ISLAND Nowingi Rocket t S Lake RA Hk Mournpall ll ya Boolga Tracks a Hattah M Nowingi MURRAY SUNSET Trk West NOWINGI LINE Hattah HKNP - TRACK WEST - Nowingi trk KONARDIN Hattah MURRAY north west TRK NORTH - Mournpall SUNSET - NOWINGI Lake North LINE TRACK EAST Cantala HATTAH - RED HATTAH - OCRE TRACK d Hattah - e HATTAH - CANTALA Robinvale R SOUTH MOURNPALL d m a TRACK RHB n HATTAH TRACK NORTH n Yanga Raak U BULOKE Boundary Plain RA Lake MSNP d Bend HATTAH - CALDER TRACK le R Raak west Chalka nva HIGHWAY EAST obi north Creek RA - R Hattah - ttah HK Hattah Ha Mournpall Robinvale Hattah South Rd Kramen Tk MURRAY SUNSET - Old Calder Hattah - Old - HATTAH HAT Hwy Calder Hwy South FIRE NORTH - THE BOILER Hattah Lake HK Lake Hattah Condoulpe Kramen MURRAY SUNSET South Lake - LAST Kia RA HOPE TRACK NORTH ANNUELLO - NORTH WEST BOUNDARY ANNUELLO - KOOLOONONG NORTH BOUNDARY - MENZIES MURRAY SUNSET WANDOWN - GALAH NORTH BOUNDARY MSNP-Last Hope ROAD NORTH south HKNP MSNP- - ZIG MSNP - WANDOWN Crozier ZAG SOUTH SOUTH -

Taylors Hill-Werribee South Sunbury-Gisborne Hurstbridge-Lilydale Wandin East-Cockatoo Pakenham-Mornington South West

TAYLORS HILL-WERRIBEE SOUTH SUNBURY-GISBORNE HURSTBRIDGE-LILYDALE WANDIN EAST-COCKATOO PAKENHAM-MORNINGTON SOUTH WEST Metro/Country Postcode Suburb Metro 3200 Frankston North Metro 3201 Carrum Downs Metro 3202 Heatherton Metro 3204 Bentleigh, McKinnon, Ormond Metro 3205 South Melbourne Metro 3206 Albert Park, Middle Park Metro 3207 Port Melbourne Country 3211 LiQle River Country 3212 Avalon, Lara, Point Wilson Country 3214 Corio, Norlane, North Shore Country 3215 Bell Park, Bell Post Hill, Drumcondra, Hamlyn Heights, North Geelong, Rippleside Country 3216 Belmont, Freshwater Creek, Grovedale, Highton, Marhsall, Mt Dunede, Wandana Heights, Waurn Ponds Country 3217 Deakin University - Geelong Country 3218 Geelong West, Herne Hill, Manifold Heights Country 3219 Breakwater, East Geelong, Newcomb, St Albans Park, Thomson, Whington Country 3220 Geelong, Newtown, South Geelong Anakie, Barrabool, Batesford, Bellarine, Ceres, Fyansford, Geelong MC, Gnarwarry, Grey River, KenneQ River, Lovely Banks, Moolap, Moorabool, Murgheboluc, Seperaon Creek, Country 3221 Staughtonvale, Stone Haven, Sugarloaf, Wallington, Wongarra, Wye River Country 3222 Clilon Springs, Curlewis, Drysdale, Mannerim, Marcus Hill Country 3223 Indented Head, Port Arlington, St Leonards Country 3224 Leopold Country 3225 Point Lonsdale, Queenscliffe, Swan Bay, Swan Island Country 3226 Ocean Grove Country 3227 Barwon Heads, Breamlea, Connewarre Country 3228 Bellbrae, Bells Beach, jan Juc, Torquay Country 3230 Anglesea Country 3231 Airleys Inlet, Big Hill, Eastern View, Fairhaven, Moggs -

Explore Nyah/Nyah West Region

Little Murray Weir Rd Explore Nyah/NyahLittle Murray Weir Rd West Region To Robinvale & Mildura LEGEND Tour Route B4OO Statewide Route Number To Balranald Vic & Sydney Highway Accredited Visitor Information Centre TOOLEYBUC Sealed Road Other Reserves & Public Land B12 MALLEE HWY MURRA Unsealed Road Lake LAKE Y COOMAROOP Railway Line Intermittent Lake To Manangatang K oraleigh Winery 7 Nyah-Vinifera Park Track 2 & Adelaide PIANGIL MALLEE HWY Pheasant Farm 8 First Rice Grown in Australian B12 L Winery ucas Lane ucas RV Park 9 Harvey’s Tank Road Mur Ferry 10 Nyah West Park V ALLEY ra 1 11 y The Flume Wire Sculptures Park The Flume 2 Wood Wood 12 The Memorial Gate 1 Gillicks B4OO Reserve NSW 3 The Ring Tree 13 Nyah Primary School WOOD WOOD 4 Nyah-Vinifera Park Track 1 14 Pioneers Cairn The Ring Tree 3 5 Nyah Township 15 Nyah’s First Irrigation Scheme 2 K oraleigh Riv 6 Nyah West Township 16 Scarred Tree er 16 HIGHW Pearse Lak Pearse Scarred Rd Tree A Nyah-Vinifera Picks Y Park Cant Rd Point Nyah-Vinifera 4 LAKE e Rd e Park Track 1 GOONIMUR Vic Byrnes La LAKE KORALEIGH WOLLARE 5 RV Park 1st Irrigation Yarraby Rd NYAH Speewa Rd 6 8 ray NYAH 7 Mur N WEST Nyah-Vinifera First Speewa Park Track 2 Rice Grown Creek Nyah-Vinifera Speewa VINIFERA Park Riv SPEEWA Forrest Rd W E er ISLAND B4OO MURRA W Y Ferry oorinen-Vinif F erry Pira Rd Pira BEVERIDGE SPEEWA ISLAND S TYNTYNDER Rd era Rd Mur ra BEVERFORD y To Chillingollah V PIRA ALLEY NSW Chillingollah Rd Riv Pheasant TYNTYNDER er Farm WOORINEN SOUTH Nowie Road NORTH 9 LAKE Harvey’s MURRAYDALE Tank -

Mallee Western

Holland Lake Silve r Ci Toupnein ty H Creek RA wy Lake Gol Gol Yelta C a l d e r H Pink Lake w y Merbein Moonlight Lake Ranfurly Mildura Lake Lake Walla Walla RA v A Lake Hawthorn n i k a e MILDURA D AIRPORT ! Kings Millewa o Irymple RA Billabong Wargan KOORLONG - SIMMONS TRACK Lake Channel Cullulleraine +$ Sturt Hwy SUNNYCLIFFS Meringur Cullulleraine - WOORLONG North Cardross Red Cliffs WETLANDS Lakes Karadoc Swamp Werrimull Sturt Hwy Morkalla RA Tarpaulin Bend RA Robinvale HATTAH - DUMOSA TRACK Nowingi Settlement M Rocket u Road RA r ra Lake RA y V a lle y H w HATTAH - RED y OCRE TRACK MURRAY SUNSET Lake - NOWINGI Bitterang Sunset RA LINE TRACK HATTAH - CALDER HIGHWAY EAST Lake Powell Raak Plain RA Lake Mournpall Chalka MURRAY SUNSET Creek RA - ROCKET LAKE TRACK WEST Lake Lockie WANDOWN - NORTH BOUNDARY MURRAY SUNSET Hattah - WILDERNESS PHEENYS TRACK MURRAY SUNSET - Millewa LAST HOPE TRACK MURRAY SUNSET South RA MURRAY SUNSET Kia RA - CALDER ANNUELLO - MURRAY SUNSET - - MENGLER ROAD HIGHWAY WEST NORTH WEST MURRAY SUNSET - +$ LAST HOPE TRACK NORTH EAST BOUNDARY LAST HOPE TRACK MURRAY SUNSET - SOUTH EAST SOUTH EAST LAST HOPE TRACK MURRAY SUNSET SOUTH EAST - TRINITA NORTH BOUNDARY +$ MURRAY SUNSET ANNUELLO - MENGLER MURRAY SUNSET - - EASTERN MURRAY SUNSET ROAD WEST TRINITA NORTH BOUNDARY - WILDERNESS BOUNDARY WEST Berrook RA Mount Crozier RA ANNUELLO - BROKEN GLASS TRACK WEST MURRAY SUNSET - SOUTH MERIDIAN ROAD ANNUELLO - SOUTH WEST C BOUNDARY ANNUELLO - a l d SOUTHERN e r BOUNDARY H w Berrook y MURRAY SUNSET - WYMLET BOUNDARY MURRAY SUNSET -

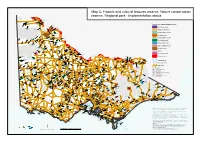

Map C: Historic and Cultural Features Reserve, Nature Conservation Reserve, Regional Park - Implementation Status

Map C: Historic and cultural features reserve, Nature conservation reserve, Regional park - implementation status Merbein South FR Psyche Bend Pumps HCF R Mildura FFR Yarrara Yatpool FFR FR Lambert Island NCR Historic and cultural features reserve Karadoc Bum bang Island Meringur NCR HCF R FFR Toltol Fully implemented FFR Lakes Powell and Carpul Wemen Mallanbool NCR FFR Nowingi Ironclad C atchment FFR and C oncrete Tank Partially implemented HR Bannerton FFR Wandown Implementation unclear Moss Tank FFR Annuello FFR FFR Bolton Kattyoong Tiega FFR Unimplemented FR FR Kulwin FFR Degraves Tank FR Kulwin Manya Wood Wood Gnarr FR Cocamba Nature conservation reserve FR Walpeup Manangatang FFR Dunstans Timberoo Towan Plains FR FFR (Lulla) FFR FFR FFR FFR Bronzewing FFR Fully implemented Murrayville FFR Chinkapook FR FFR Yarraby Chillingollah FR Koonda Nyang FFR FR Boinka FFR Lianiduck Partially implemented FR FFR Welshmans Plain FFR Dering FFR Turriff Lake Timboram FFR Waitchie FFR Implementation unclear FFR Winlaton Yetmans (Patchewollock) Wathe NCR FFR FFR Green Yassom Swamp Dartagook Unimplemented NCR Lake NCR Koondrook Paradise RP Brimy Bill Korrak Korrak HC FR FFR WR NCR Cambacanya Angels Rest Wandella Kerang RP Regional park Lake FFR FR NCR Gannawarra Red Gum Albacutya Swamp V NCR Cohuna HCFR RP Wangie FFR Tragowel Swamp Pyramid Creek Cohuna Old Fully implemented NCR Cannie NCR NCR Court House Goyura Rowland HCF R HR Towaninny NCR Flannery Red Bluff Birdcage NCR Griffith Lagoon NCR Bonegilla Unimplemented FFR NCR Bethanga FFR Towma (Lake -

33 Rd Annual Report 1981/82

SOIL CONSERVATION AUTHORITY · 33 rd Annual Report 1981/82. VICTORIA Report of the SOIL CONSERVATION AUTHORITY for the Year ended 30 June 1982 Ordered by the Legislative Assembly· to be printed MELBOURNE F D ATKINSON GOVERNMENT PRINTER 1982 No. 51 Cover: The effects of salting can be devastating. As the salty water-table rises it reaches root systems causing trees and plants to die. Salt also breaks down the soil structure making the land more prone to the various forms oferosion. The result is a desert-like landscape. 2 SOIL CONSERVATION AUTHORITY ----·-------- 378 Cotham Road, Kew, Victoria, 3101 The Honourable Evan Walker, M.l.C., 29 October 1982 Minister for Conservation. Dear Mr. Walker, In accordance with the provisions of the Soil Conservation and Land Utilization Act 1958 No. 6372, the Soil Conservation Authority submits to you for presentation to Parliament its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 1982. The Authority wishes to express its appreciation for the continued co-operation and assistance of Government departments and State instrumentalities, municipal councils and land holders. Yours sincerely, A. MITCHELL, M.Agr.Sc., D.D.A., Chairman D.N. CAHILL, B.Agr.Sc., Dip.Ag.Ex., Deputy Chairman ~M~~h~--c?- -~~ J.S. GILMORE, J.P., Member The year under review saw a change in Government. The Authority wishes to record its sincere thanks to the Honourable Vasey Houghton, Minister for Conservation from 16 June 1979 to 7 April1982. The Authority welcomes the Honourable Evan Walker to this important portfolio. 3 AIMS AND RESPONSIBILITIES The Soil Conservation Authority is a public • To ensure correct land use in water supply statutory body established in 1950. -

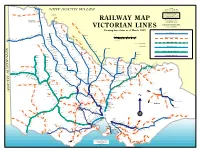

Railway Map Victorian Lines

Yelta Merbein West NOTES Mildura NEW SOUTH WALES All stations are shown with MerbeinIrymple their most recent known names. Redcliffs Abbreviations used Robinvale to Koorakee Morkalla Werrimull Karawinna Yatpool built by VR construction Meringurarrara BG = Broad Gauge (5' 3") Y Pirlta Thurla branch but never handed Benetook over to VR for traffic. Karween Merrinee SG = Standard Gauge (4' 8 1/2") Bambill Carwarp NG = Narrow Gauge (2' 6") Koorakee Boonoonar Benanee RAILWAY MAP Nowingi towards Millewa South Euston All lines shown are or were built by VR construction branch never handed over to VR for traffic, Nowingi Broad Gauge (5' 3") ownership sold to Brunswick Robinvale Plaster Mills 1942 unless otherwise shown. Balranald Bannerton Yangalake No attempt has been made to identify Yungara private railways or tourist lines being Hattah Margooya Impimi Koorkab VICTORIAN LINES run on closed VR lines Annuello Moolpa Kooloonong Trinita Koimbo Perekerten Showing line status as of March 1999 Natya Bolton Kiamal Coonimur Open BG track Kulwin Manangatang Berambong Tiega Piangil Stony Crossing Ouyen MILES Galah Leitpar Moulamein Cocamba Miralie Tueloga Walpeup Nunga 10 5 0 10 20 30 40 Mittyack Dilpurra Linga Underbool Torrita Chinkapook Nyah West Closed or out of use track Boinka Bronzewing Dhuragoon utye 0 5 10 20 30 40 50 60 T Pier Millan Coobool Panitya Chillingollah Pinnaroo Carina Murrayville Cowangie Pira Niemur KILOMETRES Gypsum Woorinen Danyo Nandaly Wetuppa I BG and 1 SG track Swan Hill Jimiringle Tempy Waitchie Wodonga open station Nyarrin Nacurrie Patchewollock Burraboi Speed Gowanford Pental Ninda Ballbank Cudgewa closed station Willa Turriff Ultima Lake Boga Wakool 2 BG and 1 SG track Yarto Sea Lake Tresco Murrabit Gama Deniliquin Boigbeat Mystic Park Yallakool Dattuck Meatian Myall Lascelles Track converted from BG to SG Berriwillock Lake Charm Caldwell Southdown Westby Koondrook Oaklands Burroin Lalbert Hill Plain Woomelang Teal Pt. -

Parish and Township Plan Numbers

Parish and Township plan numbers This is a complete list of Victorian parishes and townships, together with plan numbers assigned by the Victorian Department of Crown Lands and Survey at some point between 1950 and 1970. The list has been reproduced from the Vicmap Reference Tables on the Department of Sustainability and Environment's land information website. Browse the list or use a keyword search to identify the plan number/s for a location. The plans are listed alphabetically. Townships and parishes are inter-sorted on the list. Some entries refer to locations within parishes or townships; these entries may be duplicated. The plan number can be used to locate copies of plans that PROV holds in the series VPRS 16171 Regional Land Office Plans Digitised Reference Set. For example, using the Search within a Series page on the PROV online catalogue with series number '16171' and the text '5030' will return the specific plans relating to the township of Ballarat. In this case, searching for 'Ballaarat' by name will return al the plans in the Ballarat land district, covering much of central and western Victoria. PROV does not hold copies of plans for the locations highlighted in pale yellow below. In most cases this is because parish-level plans were not created for areas such as national parks, where there were few land transactions to record. Plans showing these locations can be downloaded from the landata website under the section 'Central Plan Office Records'. 5001 Township of Aberfeldy 2016 Parish of Angora 2001 Parish of Acheron 2017 -

Chapter 3. Landscape, People and Economy

Chapter 3. Landscape, people and economy Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 3. Landscape, people and economy Victoria’s North and Murray Water Resource Plan applies to surface water resources in the Northern Victoria and Victorian Murray water resource plan areas, and groundwater resources in Goulburn-Murray water resource plan area. This chapter provides a brief description of the landscape, people and economic drivers in the water resource plan areas. Working rivers The rivers of this water resource plan area provide many environmental, economic, and social benefits for Victorian communities. Most of northern Victoria’s rivers have been modified from their natural state to varying degrees. These modifications have affected hydrologic regimes, physical form, riparian vegetation, water quality and instream ecology. Under the Basin Plan it is not intended that these rivers and streams be restored to a pre-development state, but that they are managed as ‘working rivers’ with agreed sustainable levels of modification and use and improved ecological values and functions. 3.1 Features of Victorian Murray water resource plan area The Victorian Murray water resource plan area covers a broad range of aquatic environments from the highlands in the far east, to the Mallee region in the far west of the state. There are several full river systems in the water resource plan area, including the Kiewa and Mitta Mitta rivers. Other rivers that begin in different water resource plan areas converge with the River Murray in the Victorian Murray water resource plan area. There are a significant number of wetlands in this area, these wetlands are managed by four catchment management authorities (CMAs): Goulburn Broken, Mallee CMAs, North Central and North East and their respective land managers. -

Victoria Government Gazette No

Victoria Government Gazette No. S 23 Wednesday 26 January 2011 By Authority of Victorian Government Printer Marine Act 1988 SECTION 15 NOTICE I, Lisa Faldon, the Director Maritime Safety (as delegate of the Director, Transport Safety), on the recommendation of Tony Langdon, Acting Inspector, Water Police/Search & Rescue Squad (a member of the Victoria Police), hereby give notice under Section 15(2) of the Marine Act 1988, that until further notice bathing and the operation of vessels excluding Victoria Police vessels and those vessels authorised by Victoria Police, is prohibited on all waters south of the high water mark, and or top river bank of the Murray River between Nyah Bridge and Goon Crossing (Murrabit) and bounded by: 1. an imaginary line from Nyah Bridge to Chinkapook; 2. the railway line from Chinkapook to Quambatook; 3. the Kerang Quambatook Road from Quambatook to Kerang, and 4. the Kerang Murrabit Road from Kerang to Goon Crossing (Murrabit). Reference No. 603/2011 Dated 26 January 2011 LISA FALDON Director Maritime Safety Transport Safety Victoria SPECIAL 2 S 23 26 January 2011 Victoria Government Gazette The Victoria Government Gazette is published by Blue Star Print with the authority of the Government Printer for the State of Victoria © State of Victoria 2011 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act. Address all enquiries to the Government Printer for the State of Victoria Level 2 1 Macarthur Street Melbourne 3002 Victoria Australia How To Order Mail Order Victoria Government Gazette Level 5 460 Bourke Street Melbourne 3000 PO Box 1957 Melbourne 3001 DX 106 Melbourne ✆ Telephone (03) 8523 4601 FAX Fax (03) 9600 0478 email [email protected] Retail & Victoria Government Gazette Mail Sales Level 5 460 Bourke Street Melbourne 3000 PO Box 1957 Melbourne 3001 ✆ Telephone (03) 8523 4601 FAX Fax (03) 9600 0478 Retail Information Victoria Sales 505 Little Collins Street Melbourne 3000 ✆ Telephone 1300 366 356 FAX Fax (03) 9603 9920 Price Code A. -

Mallee Pages 6.Indd

THE MALLEE A journey through north-west Victoria ADAM McNICOL | ANDREW CHAPMAN | JAIME MURCIA | MELANIE FAITH DOVE NOEL BUTCHER | ERIN JONASSON | PHIL CAMPBELL Contents Foreword 8 An ode to the Mallee 10 Contributors 12 Where is the Mallee? 14 A short history of the Mallee 16 Chapter 1 Rainbow to Patchewollock 42 Chapter 2 Morton Plains to Murrayville 100 Chapter 3 Wycheproof to Kulwin 156 Chapter 4 Quambatook to Manangatang 202 References/Further reading 230 120 Victoria Street, Index of towns and localities 230 Ballarat East Victoria 3350 Australia Acknowledgements 231 tenbagpress.com.au First published 2020 Text © Adam McNicol 2020 Photographs © Adam McNicol, Andrew Chapman, Jaime Murcia, Melanie Faith Dove, Noel Butcher, Erin Jonasson and Phil Campbell 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN: 978-0-646-82244-0 Cover: Sunrise at a property between Hopetoun and Patchewollock AC Cover, internal design and typesetting by Philip Campbell Design Previous pages: A flock of ewes and Printed in Geelong, Australia by Adams Print lambs near the Curyo silos AC The photograph on page 17 is courtesy Robby Wirramanda. The photographs Right: A classic Mallee scene near on pages 21 and 27 are courtesy Museums Victoria. The photographs on Rainbow AC pages 23, 29 and 31 are courtesy State Library of Victoria. The photograph on Following pages: A haystack near Beulah; page 33 is courtesy Des and Maree Ryan. The photographs on page 34 are Sunrise at the Manangatang (Lulla) Flora courtesy Terry McNicol and Fauna Reserve AC 5 our journey through the mallee Where is The Mallee? Robinvale Tiega Kulwin Manangatang NEW SOUTH WALES Ouyen The part of Victoria known as the Mallee is best defined as Communicating among ourselves the exact location of Galah Cocamba Walpeup Nunga the area where the species of eucalypts known as ‘mallees’ this southern boundary was a challenge in itself.