Targeting the Tryptophan Hydroxylase 2 Gene for Functional Analysis in Mice and Serotonergic Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monoamine Oxydases Et Athérosclérose : Signalisation Mitogène Et Études in Vivo

UNIVERSITE TOULOUSE III - PAUL SABATIER Sciences THESE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE TOULOUSE III Discipline : Innovation Pharmacologique Présentée et soutenue par : Christelle Coatrieux le 08 octobre 2007 Monoamine oxydases et athérosclérose : signalisation mitogène et études in vivo Jury Monsieur Luc Rochette Rapporteur Professeur, Université de Bourgogne, Dijon Monsieur Ramaroson Andriantsitohaina Rapporteur Directeur de Recherche, INSERM, Angers Monsieur Philippe Valet Président Professeur, Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse III Madame Nathalie Augé Examinateur Chargé de Recherche, INSERM Monsieur Angelo Parini Directeur de Thèse Professeur, Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse III INSERM, U858, équipes 6/10, Institut Louis Bugnard, CHU Rangueil, Toulouse Résumé Les espèces réactives de l’oxygène (EROs) sont impliquées dans l’activation de nombreuses voies de signalisation cellulaires, conduisant à différentes réponses comme la prolifération. Les EROs, à cause du stress oxydant qu’elles génèrent, sont impliquées dans de nombreuses pathologies, notamment l’athérosclérose. Les monoamine oxydases (MAOs) sont deux flavoenzymes responsables de la dégradation des catécholamines et des amines biogènes comme la sérotonine ; elles sont une source importante d’EROs. Il a été montré qu’elles peuvent être impliquées dans la prolifération cellulaire ou l’apoptose du fait du stress oxydant qu’elles génèrent. Ce travail de thèse a montré que la MAO-A, en dégradant son substrat (sérotonine ou tyramine), active une voie de signalisation mitogène particulière : la voie métalloprotéase- 2/sphingolipides (MMP2/sphingolipides), et contribue à la prolifération de cellules musculaire lisses vasculaires induite par ces monoamines. De plus, une étude complémentaire a confirmé l’importance des EROs comme stimulus mitogène (utilisation de peroxyde d’hydrogène exogène), et a décrit plus spécifiquement les étapes en amont de l’activation de MMP2, ainsi que l’activation par la MMP2 de la sphingomyélinase neutre (première enzyme de la cascade des sphingolipides). -

MDR-1, Bcl-Xl, H. Pylori, and Wnt&Sol;Β-Catenin Signalling in the Adult Stomach

Laboratory Investigation (2012) 92, 1670–1673 & 2012 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0023-6837/12 $32.00 EDITORIAL MDR-1, Bcl-xL, H. pylori, and Wnt/b-catenin signalling in the adult stomach: how much is too much? R John MacLeod Laboratory Investigation (2012) 92, 1670–1673; doi:10.1038/labinvest.2012.151 ultiple drug resistance (MDR) is a interaction between the antiapoptotic protein major cause of failure of che- Bcl-xL and MDR-1. Knockdown of MDR-1 motherapy in cancer treatment. increases the apoptotic index of these cells exposed The membrane transporter P-gly- to oxidative stress consistent with a role for MDR- coprotein (MDR-1, Pgp) encoded 1 in apoptosis. Several questions emerge from Mby the adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette, these findings. The first is why is MDR-1 increased subfamily B, member 1 is the main mechanism for in some HP-positive mucosa but in 100% of the decreased intracellular drug accumulation in MDR intestinal metaplasia samples? A likely causative cancer.1 Increases in Mdr-1 expression prevent effector of the increase in MDR-1 is the activation tumor cells from a variety of induced apoptosis, of canonical or Wnt/b-catenin signaling. It has but how this occurs is poorly understood. It is been known for a dozen years that the MDR-1 essential to understand how this occurs to be able gene may be stimulated by Tcf4.4 Yamada et al4 to design effective therapeutic interventions. The clearly demonstrated the presence of Tcf4 sites on study by Rocco et al2 (this issue) clearly shows that the MDR-1 promoter and showed that MDR-1 in the mitochondria of gastric cancer cell lines protein had substantially increased in adenomas MDR1 physically interacts with Bcl-xL, a well- and colon cancer. -

Table S1 the Four Gene Sets Derived from Gene Expression Profiles of Escs and Differentiated Cells

Table S1 The four gene sets derived from gene expression profiles of ESCs and differentiated cells Uniform High Uniform Low ES Up ES Down EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol 269261 Rpl12 11354 Abpa 68239 Krt42 15132 Hbb-bh1 67891 Rpl4 11537 Cfd 26380 Esrrb 15126 Hba-x 55949 Eef1b2 11698 Ambn 73703 Dppa2 15111 Hand2 18148 Npm1 11730 Ang3 67374 Jam2 65255 Asb4 67427 Rps20 11731 Ang2 22702 Zfp42 17292 Mesp1 15481 Hspa8 11807 Apoa2 58865 Tdh 19737 Rgs5 100041686 LOC100041686 11814 Apoc3 26388 Ifi202b 225518 Prdm6 11983 Atpif1 11945 Atp4b 11614 Nr0b1 20378 Frzb 19241 Tmsb4x 12007 Azgp1 76815 Calcoco2 12767 Cxcr4 20116 Rps8 12044 Bcl2a1a 219132 D14Ertd668e 103889 Hoxb2 20103 Rps5 12047 Bcl2a1d 381411 Gm1967 17701 Msx1 14694 Gnb2l1 12049 Bcl2l10 20899 Stra8 23796 Aplnr 19941 Rpl26 12096 Bglap1 78625 1700061G19Rik 12627 Cfc1 12070 Ngfrap1 12097 Bglap2 21816 Tgm1 12622 Cer1 19989 Rpl7 12267 C3ar1 67405 Nts 21385 Tbx2 19896 Rpl10a 12279 C9 435337 EG435337 56720 Tdo2 20044 Rps14 12391 Cav3 545913 Zscan4d 16869 Lhx1 19175 Psmb6 12409 Cbr2 244448 Triml1 22253 Unc5c 22627 Ywhae 12477 Ctla4 69134 2200001I15Rik 14174 Fgf3 19951 Rpl32 12523 Cd84 66065 Hsd17b14 16542 Kdr 66152 1110020P15Rik 12524 Cd86 81879 Tcfcp2l1 15122 Hba-a1 66489 Rpl35 12640 Cga 17907 Mylpf 15414 Hoxb6 15519 Hsp90aa1 12642 Ch25h 26424 Nr5a2 210530 Leprel1 66483 Rpl36al 12655 Chi3l3 83560 Tex14 12338 Capn6 27370 Rps26 12796 Camp 17450 Morc1 20671 Sox17 66576 Uqcrh 12869 Cox8b 79455 Pdcl2 20613 Snai1 22154 Tubb5 12959 Cryba4 231821 Centa1 17897 -

Functional Analysis of Chimeric Lysin Motif Domain Receptors Mediating Nod Factor-Induced Defense Signaling in Arabidopsis Thali

The Plant Journal (2014) 78, 56–69 doi: 10.1111/tpj.12450 Functional analysis of chimeric lysin motif domain receptors mediating Nod factor-induced defense signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana and chitin-induced nodulation signaling in Lotus japonicus Wei Wang1,2, Zhi-Ping Xie1,* and Christian Staehelin1,* 1State Key Laboratory of Biocontrol and Guangdong Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, School of Life Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, East Campus, Guangzhou 510006, China, and 2Anhui Key Laboratory of Plant Genetics & Breeding, School of Life Sciences, Anhui Agricultural University, 130 Changjiang West Road, Hefei, Anhui 230036, China Received 12 October 2013; revised 11 January 2014; accepted 16 January 2014; published online 8 February 2014. *For correspondence (e-mails [email protected] or [email protected]). SUMMARY The expression of chimeric receptors in plants is a way to activate specific signaling pathways by corre- sponding signal molecules. Defense signaling induced by chitin from pathogens and nodulation signaling of legumes induced by rhizobial Nod factors (NFs) depend on receptors with extracellular lysin motif (LysM) domains. Here, we constructed chimeras by replacing the ectodomain of chitin elicitor receptor kinase 1 (AtCERK1) of Arabidopsis thaliana with ectodomains of NF receptors of Lotus japonicus (LjNFR1 and LjNFR5). The hybrid constructs, named LjNFR1–AtCERK1 and LjNFR5–AtCERK1, were expressed in cerk1-2, an A. thaliana CERK1 mutant lacking chitin-induced defense signaling. When treated with NFs from Rhizobi- um sp. NGR234, cerk1-2 expressing both chimeras accumulated reactive oxygen species, expressed chitin- responsive defense genes and showed increased resistance to Fusarium oxysporum. In contrast, expression of a single chimera showed no effects. -

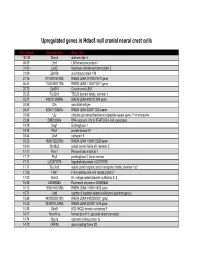

Supp Table 1.Pdf

Upregulated genes in Hdac8 null cranial neural crest cells fold change Gene Symbol Gene Title 134.39 Stmn4 stathmin-like 4 46.05 Lhx1 LIM homeobox protein 1 31.45 Lect2 leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 31.09 Zfp108 zinc finger protein 108 27.74 0710007G10Rik RIKEN cDNA 0710007G10 gene 26.31 1700019O17Rik RIKEN cDNA 1700019O17 gene 25.72 Cyb561 Cytochrome b-561 25.35 Tsc22d1 TSC22 domain family, member 1 25.27 4921513I08Rik RIKEN cDNA 4921513I08 gene 24.58 Ofa oncofetal antigen 24.47 B230112I24Rik RIKEN cDNA B230112I24 gene 23.86 Uty ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat gene, Y chromosome 22.84 D8Ertd268e DNA segment, Chr 8, ERATO Doi 268, expressed 19.78 Dag1 Dystroglycan 1 19.74 Pkn1 protein kinase N1 18.64 Cts8 cathepsin 8 18.23 1500012D20Rik RIKEN cDNA 1500012D20 gene 18.09 Slc43a2 solute carrier family 43, member 2 17.17 Pcm1 Pericentriolar material 1 17.17 Prg2 proteoglycan 2, bone marrow 17.11 LOC671579 hypothetical protein LOC671579 17.11 Slco1a5 solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a5 17.02 Fbxl7 F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 7 17.02 Kcns2 K+ voltage-gated channel, subfamily S, 2 16.93 AW493845 Expressed sequence AW493845 16.12 1600014K23Rik RIKEN cDNA 1600014K23 gene 15.71 Cst8 cystatin 8 (cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic) 15.68 4922502D21Rik RIKEN cDNA 4922502D21 gene 15.32 2810011L19Rik RIKEN cDNA 2810011L19 gene 15.08 Btbd9 BTB (POZ) domain containing 9 14.77 Hoxa11os homeo box A11, opposite strand transcript 14.74 Obp1a odorant binding protein Ia 14.72 ORF28 open reading -

Structural Engineering of a Phage Lysin That Targets Gram-Negative Pathogens

Structural engineering of a phage lysin that targets Gram-negative pathogens Petra Lukacika, Travis J. Barnarda, Paul W. Kellerb, Kaveri S. Chaturvedic, Nadir Seddikia,JamesW.Fairmana, Nicholas Noinaja, Tara L. Kirbya, Jeffrey P. Hendersonc, Alasdair C. Stevenb, B. Joseph Hinnebuschd, and Susan K. Buchanana,1 aLaboratory of Molecular Biology, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; bLaboratory of Structural Biology, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda,MD 20892; cCenter for Women’s Infectious Diseases Research, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110; and dLaboratory of Zoonotic Pathogens, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Hamilton, MT 59840 Edited by* Brian W. Matthews, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, and approved April 18, 2012 (received for review February 27, 2012) Bacterial pathogens are becoming increasingly resistant to antibio- ∼10 kb plasmid called pPCP1 (7). Pla facilitates invasion in bu- tics. As an alternative therapeutic strategy, phage therapy reagents bonic plague and, as such, is an important virulence factor (8, 9). containing purified viral lysins have been developed against Gram- When strains lose the pPCP1 plasmid, they are killed by pesticin positive organisms but not against Gram-negative organisms due thus ensuring maximal virulence in the bacterial population. to the inability of these types of drugs to cross the bacterial outer Bacteriocins belong to two classes. Type A bacteriocins depend membrane. We solved the crystal structures of a Yersinia pestis on the Tolsystem to traverse the outer membrane, whereas type B outer membrane transporter called FyuA and a bacterial toxin bacteriocins require the Ton system. -

The Forkhead-Box Family of Transcription Factors: Key Molecular Players in Colorectal Cancer Pathogenesis Paul Laissue

Laissue Molecular Cancer (2019) 18:5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-019-0938-x REVIEW Open Access The forkhead-box family of transcription factors: key molecular players in colorectal cancer pathogenesis Paul Laissue Abstract Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly occurring cancer worldwide and the fourth most frequent cause of death having an oncological origin. It has been found that transcription factors (TF) dysregulation, leading to the significant expression modifications of genes, is a widely distributed phenomenon regarding human malignant neoplasias. These changes are key determinants regarding tumour’s behaviour as they contribute to cell differentiation/proliferation, migration and metastasis, as well as resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. The forkhead box (FOX) transcription factor family consists of an evolutionarily conserved group of transcriptional regulators engaged in numerous functions during development and adult life. Their dysfunction has been associated with human diseases. Several FOX gene subgroup transcriptional disturbances, affecting numerous complex molecular cascades, have been linked to a wide range of cancer types highlighting their potential usefulness as molecular biomarkers. At least 14 FOX subgroups have been related to CRC pathogenesis, thereby underlining their role for diagnosis, prognosis and treatment purposes. This manuscript aims to provide, for the first time, a comprehensive review of FOX genes’ roles during CRC pathogenesis. The molecular and functional characteristics of most relevant FOX molecules (FOXO, FOXM1, FOXP3) have been described within the context of CRC biology, including their usefulness regarding diagnosis and prognosis. Potential CRC therapeutics (including genome-editing approaches) involving FOX regulation have also been included. Taken together, the information provided here should enable a better understanding of FOX genes’ function in CRC pathogenesis for basic science researchers and clinicians. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Development of Phage Lysins As Novel Therapeutics: a Historical Perspective

viruses Essay Development of Phage Lysins as Novel Therapeutics: A Historical Perspective Vincent A. Fischetti ID Laboratory of Bacterial Pathogenesis and Immunology, The Rockefeller University, 1230 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065, USA; [email protected] Received: 10 May 2018; Accepted: 5 June 2018; Published: 7 June 2018 Abstract: Bacteriophage lysins and related bacteriolytic enzymes are now considered among the top antibiotic alternatives for solving the mounting resistance problem. Over the past 17 years, lysins have been widely developed against Gram-positive and recently Gram-negative pathogens, and successfully tested in a variety of animal models to demonstrate their efficacy. A lysin (CF-301) directed to methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has effectively completed phase 1 human clinical trials, showing safety in this novel therapeutic class. To validate efficacy, CF-301 is currently the first lysin to enter phase 2 human trials to treat hospitalized patients with MRSA bacteremia or endocarditis. If successful, it could be the defining moment leading to the acceptance of lysins as an alternative to small molecule antibiotics. This article is a detailed account of events leading to the first therapeutic use and ultimate development of phage-encoded lysins as novel anti-infectives. Keywords: phage; lysins; endolysins; lytic enzymes; discovery; therapeutic; antibiotic resistance; alternative to antibiotics 1. Preface Since 2001, when our first paper was published describing the in vivo use of phage enzymes as potential therapeutics, I have been asked many times: “How did you think of doing this?” This article is a detailed answer to that question. I certainly was not the only person in the world working on phage lysins at the time; however, I was one of the few working with a highly-active lysin against Gram-positive bacteria. -

The Neurochemical Consequences of Aromatic L-Amino Acid Decarboxylase Deficiency

The neurochemical consequences of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency Submitted By: George Francis Gray Allen Department of Molecular Neuroscience UCL Institute of Neurology Queen Square, London Submitted November 2010 Funded by the AADC Research Trust, UK Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University College London (UCL) 1 I, George Allen confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed………………………………………………….Date…………………………… 2 Abstract Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) catalyses the conversion of 5- hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) and L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-dopa) to the neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine respectively. The inherited disorder AADC deficiency leads to a severe deficit of serotonin and dopamine as well as an accumulation of 5-HTP and L-dopa. This thesis investigated the potential role of 5- HTP/L-dopa accumulation in the pathogenesis of AADC deficiency. Treatment of human neuroblastoma cells with L-dopa or dopamine was found to increase intracellular levels of the antioxidant reduced glutathione (GSH). However inhibiting AADC prevented the GSH increase induced by L-dopa. Furthermore dopamine but not L-dopa, increased GSH release from human astrocytoma cells, which do not express AADC activity. GSH release is the first stage of GSH trafficking from astrocytes to neurons. This data indicates dopamine may play a role in controlling brain GSH levels and consequently antioxidant status. The inability of L-dopa to influence GSH concentrations in the absence of AADC or with AADC inhibited indicates GSH trafficking/metabolism may be compromised in AADC deficiency. -

Table 1A SIRT1 Differential Binding Gene List Down

Rp1 Rb1cc1 Pcmtd1 Mybl1 Sgk3 Cspp1 Arfgef1 Cpa6 Kcnb2 Stau2 Jph1 Paqr8 Kcnq5 Rims1 Smap1 Bai3 Prim2 Bag2 Zfp451 Dst Uggt1 4632411B12Rik Fam178b Tmem131 Inpp4a 2010300C02Rik Rev1 Aff3 Map4k4 Il1r1 Il1rl2 Tgfbrap1 Col3a1 Wdr75 Tmeff2 Hecw2 Boll Plcl1 Satb2 Aox4 Mpp4 Gm973 Carf Nbeal1 Pard3b Ino80d Adam23 Dytn Pikfyve Atic Fn1 Smarcal1 Tns1 Arpc2 Pnkd Ctdsp1 Usp37 Acsl3 Cul3 Dock10 Col4a4 Col4a3 Mff Wdr69 Pid1 Sp110 Sp140 Itm2c 2810459M11Rik Dis3l2 Chrng Gigyf2 Ugt1a7c Ugt1a6b Hjurp A730008H23Rik Trpm8 Kif1a D1Ertd622e Pam Cntnap5b Rnf152 Phlpp1 Clasp1 Gli2 Dpp10 Tmem163 Zranb3 Pfkfb2 Pigr Rbbp5 Sox13 Ppfia4 Rabif Kdm5b Ppp1r12b Lgr6 Pkp1 Kif21b Nr5a2 Dennd1b Trove2 Pdc Hmcn1 Ncf2 Nmnat2 Lamc2 Cacna1e Xpr1 Tdrd5 Fam20b Ralgps2 Sec16b Astn1 Pappa2 Tnr Klhl20 Dnm3 Bat2l2 4921528O07Rik Scyl3 Dpt Mpzl1 Creg1 Cd247 Gm4846 Lmx1a Pbx1 Ddr2 Cd244 Cadm3 Fmn2 Grem2 Rgs7 Fh1 Wdr64 Pld5 Cep170 Akt3 Pppde1 Smyd3 Parp1 Enah Capn8 Susd4 Mosc1 Rrp15 Gpatch2 Esrrg Ptpn14 Smyd2 Tmem206 Nek2 Traf5 Hhat Cdnf Fam107b Camk1d Cugbp2 Gata3 Itih5 Sfmbt2 Itga8 Pter Rsu1 Ptpla Slc39a12 Cacnb2 Nebl Pip4k2a Abi1 Tbpl2 Pnpla7 Kcnt1 Camsap1 Nacc2 Gpsm1 Sec16a Fam163b Vav2 Olfm1 Tsc1 Med27 Rapgef1 Pkn3 Zer1 Prrx2 Gpr107 Ass1 Nup214 Bat2l Dnm1 Ralgps1 Fam125b Mapkap1 Hc Ttll11 Dennd1a Olfml2a Scai Arhgap15 Gtdc1 Mbd5 Kif5c Lypd6b Lypd6 Fmnl2 Arl6ip6 Galnt13 Acvr1 Ccdc148 Dapl1 Tanc1 Ly75 Gcg Kcnh7 Cobll1 Scn3a Scn9a Scn7a Gm1322 Stk39 Abcb11 Slc25a12 Metapl1 Pdk1 Rapgef4 B230120H23Rik Gpr155 Wipf1 Pde11a Prkra Gm14461 Pde1a Calcrl Olfr1033 Mybpc3 F2 Arhgap1 Ambra1 Dgkz Creb3l1 -

Pituitary Stem Cells Produce Paracrine WNT Signals to Control The

RESEARCH ARTICLE Pituitary stem cells produce paracrine WNT signals to control the expansion of their descendant progenitor cells John P Russell1, Xinhong Lim2,3, Alice Santambrogio1,4, Val Yianni1, Yasmine Kemkem5, Bruce Wang6,7, Matthew Fish6, Scott Haston8, Anae¨ lle Grabek9, Shirleen Hallang1, Emily J Lodge1, Amanda L Patist1, Andreas Schedl9, Patrice Mollard5, Roel Nusse6, Cynthia L Andoniadou1,4* 1Centre for Craniofacial and Regenerative Biology, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom; 2Skin Research Institute of Singapore, Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore, Singapore; 3Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore; 4Department of Medicine III, University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, Technische Universita¨ t Dresden, Dresden, Germany; 5Institute of Functional Genomics (IGF), University of Montpellier, CNRS, Montpellier, France; 6Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Stanford University School of Medicine, Department of Developmental Biology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, United States; 7Department of Medicine and Liver Center, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, United States; 8Developmental Biology and Cancer, Birth Defects Research Centre, UCL GOS Institute of Child Health, London, United Kingdom; 9Universite´ Coˆte d’Azur, Inserm, CNRS, Nice, France Abstract In response to physiological demand, the pituitary gland generates new hormone- secreting cells from committed progenitor cells throughout life. It remains unclear to what extent pituitary stem cells (PSCs), which uniquely express SOX2, contribute to pituitary growth and renewal. Moreover, neither the signals that drive proliferation nor their sources have been *For correspondence: elucidated. We have used genetic approaches in the mouse, showing that the WNT pathway is [email protected] essential for proliferation of all lineages in the gland.