What Is Language? Learning Goals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Individualism, Structuralism, and Climate Change

1 2 3 Individualism, Structuralism, and Climate Change 4 5 Michael Brownstein 6 Alex Madva 7 Daniel Kelly 8 9 10 Abstract 11 12 Scholars and activists working on climate change often distinguish between “individual” and 13 “structural” approaches to decarbonization. The former concern behaviors and consumption 14 choices individual citizens can make to reduce their “personal carbon footprint” (e.g., eating less 15 meat). The latter concern institutions that shape collective action, focusing instead on state and 16 national laws, industrial policies, and international treaties. While the distinction between 17 individualism and structuralism—the latter of which we take to include “institutional”, “systemic”, 18 and “collectivist” approaches—is intuitive and ubiquitous, the two approaches are often portrayed 19 as oppositional, as if one or the other is the superior route to decarbonization. We argue instead for 20 a more symbiotic conception of structural and individual reform. 21 22 23 1. Introduction 24 Scholars and activists working on climate change often distinguish between “individual” and 25 “structural” approaches to decarbonization. The former concern behaviors and consumption 26 choices individual citizens can make to reduce their “personal carbon footprint” (e.g., eating less 27 meat). The latter concern institutions that shape collective action, focusing instead on state and 28 national laws, industrial policies, and international treaties. While the distinction between 29 individualism and structuralism—the latter of which we take to include “institutional”, “systemic”, 30 and “collectivist” approaches—is intuitive and ubiquitous, the two approaches are often portrayed 31 as oppositional, as if one or the other is the superior route to decarbonization. -

Limits on Bilingualism Revisited: Stress 'Deafness' in Simultaneous French

Cognition 114 (2010) 266–275 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Cognition journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/COGNIT Limits on bilingualism revisited: Stress ‘deafness’ in simultaneous French–Spanish bilinguals Emmanuel Dupoux a,*, Sharon Peperkamp a,b, Núria Sebastián-Gallés c a Laboratoire de Sciences Cognitives et Psycholinguistique, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Département d’Etudes Cognitives, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 29 Rue d’Ulm, 75005 Paris, France b Département des Sciences du Langage, Université de Paris VIII, Saint-Denis, France c Brain and Cognition Unit, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain article info abstract Article history: We probed simultaneous French–Spanish bilinguals for the perception of Spanish lexical Received 29 September 2008 stress using three tasks, two short-term memory encoding tasks and a speeded lexical deci- Revised 30 September 2009 sion. In all three tasks, the performance of the group of simultaneous bilinguals was inter- Accepted 1 October 2009 mediate between that of native speakers of Spanish on the one hand and French late learners of Spanish on the other hand. Using a composite stress ‘deafness’ index measure computed over the results of the three tasks, we found that the performance of the simul- Keywords: taneous bilinguals is best fitted by a bimodal distribution that corresponds to a mixture of Speech perception the performance distributions of the two control groups. Correlation analyses showed that Simultaneous bilingualism Phonology the variables explaining language dominance are linked to early language exposure. These Stress findings are discussed in light of theories of language processing in bilinguals. Ó 2009 Elsevier B.V. -

Language Development Language Development

Language Development rom their very first cries, human beings communicate with the world around them. Infants communicate through sounds (crying and cooing) and through body lan- guage (pointing and other gestures). However, sometime between 8 and 18 months Fof age, a major developmental milestone occurs when infants begin to use words to speak. Words are symbolic representations; that is, when a child says “table,” we understand that the word represents the object. Language can be defined as a system of symbols that is used to communicate. Although language is used to communicate with others, we may also talk to ourselves and use words in our thinking. The words we use can influence the way we think about and understand our experiences. After defining some basic aspects of language that we use throughout the chapter, we describe some of the theories that are used to explain the amazing process by which we Language9 A system of understand and produce language. We then look at the brain’s role in processing and pro- symbols that is used to ducing language. After a description of the stages of language development—from a baby’s communicate with others or first cries through the slang used by teenagers—we look at the topic of bilingualism. We in our thinking. examine how learning to speak more than one language affects a child’s language develop- ment and how our educational system is trying to accommodate the increasing number of bilingual children in the classroom. Finally, we end the chapter with information about disorders that can interfere with children’s language development. -

Similarities and Differences Between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au Similarities and Differences between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology Yuki Itani-Adams1, Junko Iwasaki2, Satomi Kawaguchi3* 1ANU College of Asia & the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 2601, Australia 2School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, 2 Bradford Street, Mt Lawley WA 6050, Australia 3School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Bullecourt Ave, Milperra NSW 2214, Australia Corresponding Author: Satomi Kawaguchi , E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This paper compares the acquisition of Japanese morphology of two bilingual children who had Received: June 14, 2017 different types of exposure to Japanese language in Australia: a simultaneous bilingual child Accepted: August 14, 2017 who had exposure to both Japanese and English from birth, and a successive bilingual child Published: December 01, 2017 who did not have regular exposure to Japanese until he was six years and three months old. The comparison is carried out using Processability Theory (PT) (Pienemann 1998, 2005) as a Volume: 6 Issue: 7 common framework, and the corpus for this study consists of the naturally spoken production Special Issue on Language & Literature of these two Australian children. The results show that both children went through the same Advance access: September 2017 developmental path in their acquisition of the Japanese morphological structures, indicating that the same processing mechanisms are at work for both types of language acquisition. However, Conflicts of interest: None the results indicate that there are some differences between the two children, including the rate Funding: None of acquisition, and the kinds of verbal morphemes acquired. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Constructing Kallipolis: the Political Argument of Plato's Socratic Dialogues

Constructing Kallipolis: The Political Argument of Plato's Socratic Dialogues The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Muller, Joe Pahl Williams. 2016. Constructing Kallipolis: The Political Argument of Plato's Socratic Dialogues. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493293 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Constructing Kallipolis: The Political Argument of Plato’s Socratic Dialogues A dissertation presented by Joe Pahl Williams Muller to The Department of Government in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Political Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 Joe Pahl Williams Muller All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: Joe Pahl Williams Muller Professor Eric Nelson Professor Rusty Jones Constructing Kallipolis: The Political Argument of Plato’s Socratic Dialogues Abstract This dissertation examines the political argument of Plato’s Socratic dialogues. Common interpretations of these texts suggest, variously: (1) that Socrates does not offer much in the way of a political theory; (2) that Socrates does reflect on politics but ultimately rejects political in- stitutions as irrelevant to his ethical concerns; (3) that Socrates arrives at a political theory that either accepts or even celebrates free and demo- cratic political arrangements. -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

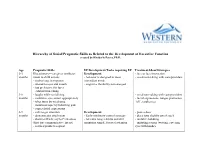

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

The Influence of Initial Exposure on Lexical

Journal of Memory and Language Journal of Memory and Language 52 (2005) 240–255 www.elsevier.com/locate/jml The influence of initial exposure on lexical representation: Comparing early and simultaneous bilinguals Nu´ria Sebastia´n-Galle´s*, Sagrario Echeverrı´a, Laura Bosch Cognitive Neuroscience Group, Parc Cientı´fic UB-Hospital Sant Joan de De´u, Edifici Docent, c/ Sta. Rosa, 39-57 4a planta, 08950 Esplugues, Barcelona, Spain Received 8 March 2004; revision received 3 November 2004 Abstract The representation of L2 words and non-words was analysed in a series of three experiments. Catalan-Spanish bilinguals, differing in terms of their L1 and the age of exposure to their L2 (since birth—simultaneous bilinguals— or starting in early childhood—early sequential bilinguals), were asked to perform a lexical decision task on Catalan words and non-words. The non-words were based on real words, but with one vowel changed: critically, this vowel change could involve a Catalan contrast that Spanish natives find difficult to perceive. The results confirmed previous data indicating that in spite of early, intensive exposure, Spanish-Catalan bilinguals fail to perceive certain Catalan contrasts, and that this failure has consequences at the lexical level. Further, the results from simultaneous bilinguals show: (a) that even in the case of bilinguals who are exposed to both languages from birth, a dominant language prevails; and (b) that simultaneous bilinguals do not attain the same level of proficiency as early bilinguals in their first language. Ó 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Speech perception; Bilingualism; Spanish; Catalan; Vowel perception; Early exposure; Sensitive period; Lexicon How early must an individual learn a second lan- longer assume that there is a more or less sudden end guage to attain native performance? Popular wisdom to an individualÕs ability to master a second language, has it that puberty is the upper limit for ‘‘perfect’’ sec- but hold that the loss of the acquisition capacity is pro- ond language acquisition. -

Linguistic Scaffolds for Writing Effective Language Objectives

Linguistic Scaffolds for Writing Effective Language Objectives An effectively written language objective: • Stems form the linguistic demands of a standards-based lesson task • Focuses on high-leverage language that will serve students in other contexts • Uses active verbs to name functions/purposes for using language in a specific student task • Specifies target language necessary to complete the task • Emphasizes development of expressive language skills, speaking and writing, without neglecting listening and reading Sample language objectives: Students will articulate main idea and details using target vocabulary: topic, main idea, detail. Students will describe a character’s emotions using precise adjectives. Students will revise a paragraph using correct present tense and conditional verbs. Students will report a group consensus using past tense citation verbs: determined, concluded. Students will use present tense persuasive verbs to defend a position: maintain, contend. Language Objective Frames: Students will (function: active verb phrase) using (language target) . Students will use (language target) to (function: active verb phrase) . Active Verb Bank to Name Functions for Expressive Language Tasks articulate defend express narrate share ask define identify predict state compose describe justify react to summarize compare discuss label read rephrase contrast elaborate list recite revise debate explain name respond write Language objectives are most effectively communicated with verb phrases such as the following: Students will point out similarities between… Students will express agreement… Students will articulate events in sequence… Students will state opinions about…. Sample Noun Phrases Specifying Language Targets academic vocabulary complete sentences subject verb agreement precise adjectives complex sentences personal pronouns citation verbs clarifying questions past-tense verbs noun phrases prepositional phrases gerunds (verb + ing) 2011 Kate Kinsella, Ed.D. -

Linguistics As a Resouvce in Language Planning. 16P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 095 698 FL 005 720 AUTHOR Garvin, Paul L. TITLE' Linguistics as a Resouvce in Language Planning. PUB DATE Jun 73 NOTE 16p.; PaFPr presented at the Symposium on Sociolinguistics and Language Planning (Mexico City, Mexico, June-July, 1973) EPRS PPICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Applied Linguistics; Language Development; *Language Planning; Language Role; Language Standardization; Linguistics; Linguistic Theory; Official Languages; Social Planning; *Sociolinguistics ABSTPACT Language planning involves decisions of two basic types: those pertaining to language choice and those pertaining to language development. linguistic theory is needed to evaluate the structural suitability of candidate languages, since both official and national languages mast have a high level of standardizaticn as a cultural necessity. On the other hand, only a braodly conceived and functionally oriented linguistics can serve as a basis for choosiag one language rather than another. The role of linguistics in the area of language development differs somewhat depending on whether development is geared in a technological and scientific or a literary, artistic direction. In the first case, emphasis is on the development of terminologies, and in the second case, on that of grammatical devices and styles. Linguistics can provide realistic and practical arguments in favor of language development, and a detailed, technical understanding of such development, as well as methodological skills. Linguists can and must function as consultants to those who actually make decisions about language planning. For too long linguists have pursued only those aims generated within their own field. They must now broaden their scope to achieve the kind of understanding of language that is necessary for a productive approach to concrete language problems. -

New Paradigm for the Study of Simultaneous V. Sequential Bilingualism

New Paradigm for the Study of Simultaneous v. Sequential Bilingualism Suzanne Flynn1, Claire Foley1 and Inna Vinnitskaya2 1MIT and 2University of Ottawa 1. Introduction Mastering multiple languages is a commonplace linguistic achievement for most of the world’s population. Chomsky (in Mukherji et al. 2000) notes that “In most of human history and in most parts of the world today, children grow up speaking a variety of languages…” Clearly, multilingualism “is just a natural state of the human mind.” Notably, most of this language learning occurs in untutored, naturalistic settings and throughout the lifespan of an individual. The false sense of language homogeneity and monolingualism that is often heralded in the United States, at least in certain regional sections, is clearly a historical artifact. As Chomsky notes: Even in the United States the idea that people speak one language is not true. Everyone grows up hearing many different languages. Sometimes they are called “dialects or stylistic variants or whatever” but they are really different languages. It is just that they are so close to each other that we don’t bother calling them different languages (Chomsky, in Mukherji et al., 2000:19 ) A conclusion is that every individual, by virtue of living within a community, is bilingual1 in some sense. Further, this means that in the same sense there is essentially universal multilingualism in the world. Despite the centrality of multilingualism to the human experience, however, questions persist concerning how learners construct new language