Download from the WCPFC’S Website Until an Automated Extraction Functionality Is Made Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suggested Itinerary – 5 Days/6 Nights in Tahiti

Suggested Itinerary – 5 days/6 nights in Tahiti ** Sightseeing, excursions and entertainment described are not included. They are suggestions that can be confirmed in advance, or in Tahiti at an additional cost. Day 1: Los Angeles to Tahiti This afternoon, depart Los Angeles on a nonstop, Air Tahiti Nui flight, which will arrive in Papeete, Tahiti later this evening. The flight time is approximately 8 hours and the time zone is just three hours behind the west coast. Enjoy complimentary dinning, drinks and movies onboard your Air Tahiti Nui flight. Tahitian Greeting upon arrival and transfer to your hotel. Accommodation - 6 Nights: Radisson Plaza Resort Tahiti – Ocean View Room – OR Manava Suite Resort Tahiti Le Meridien Tahiti – OR InterContinental Tahiti Resort & Spa Day 2: Tahiti – Discover Papeete Take a locally arranged tour, or hotel shuttle, to discover the city of Papeete – Take a walking tour of Old Papeete, visit “Le Marche”, the galleries and colorful shops along the waterfront, Town Hall and The Cathedral, the Pearl Museum and shop for souvenirs and exquisite Tahitian Black Pearls. This evening, perhaps attend an exciting Tahitian Dance Show with Dinner. Day 3: Tahiti – Island Road Trip Take a full day, Circle Island Tour. A Guided Tour by bus, or rent a car to see the island’s sights at your own pace. Picnic and go for a swim at a black sand beach. Visit the Botanical Gardens, Gauguin Museum, Mara’a Grotto, Arahoho Blowhole, Fautaua Waterfall, Mara’e (temple) Arahurahu and views from the Taravao Plateau. This evening dinner at “Les Roulottes”. Every evening at Place Vai’ete, on Papeete’s waterfront many different “Roulottes”, or food wagons, offer great variety of island cuisine and desserts. -

Pacific Island Countries and Territories Issued: 19 February 2008

OCHA Regional Office for Asia Pacific Pacific Island Countries and Territories Issued: 19 February 2008 OCHA Presence in the Pacific Northern Papua New Guinea Fiji Mariana Humanitarian Affairs Unit (HAU), PNG Regional Disaster Response Islands (U.S.) UN House , Level 14, DeloitteTower, Advisor (RDRA), Fiji Douglas Street, PO Box 1041, 360 Victoria Parade, 3rd Floor Fiji +10 Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea Development Bank Building, Suva, FIJI Tel: +675 321 2877 Tel: +679 331 6760, +679 331 6761 International Date Line Fax: +675 321 1224 Fax: +679 330 9762 Saipan Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Head: Vini Talai Head: Peter Muller Agana +12 Guam (U.S.) Pacific Ocean +10 MARSHALL ISLANDS Legend Depth (m) OCHA Presence Below 5,000 1,001 to 2,000 MICRONESIA (FSO) Koror Majuro Country capital Palikir 4,001 to 5,000 501 to 1,000 Territory capital PALAU +11 Illustrative boundary 3,001 to 4,000 101 to 500 +9 +10 Time difference with UTC 2,001 to 3,000 o to 100 Tarawa (New York: UTC -5 Equator NAURU Geneva: UTC +1) IMPORTANT NOTE: The boundaries on this map are for illustrative purposes only Yaren Naming Convention and were derived from the map ’The +12 +12 KIRIBATI UN MEMBER STATE Pacific Islands’ published in 2004 by the Territory or Associated State Secretariat of the Pacific Community. INDONESIA TUVALU -11 -10 PAPUA NEW GUINEA United Nations Office for the Coordination +10 +12 of Humanitarian affairs (OCHA) Funafuti Toke lau (N.Z.) Regional Office for Asia Pacific (ROAP) Honiara Executive Suite, 2nd Floor, -10 UNCC Building, -

A Local's Guide to Papeete Visiting Tahiti? You Don't Have to Rush Off to the Outer Islands Too Quickly

A local's guide to Papeete Visiting Tahiti? You don't have to rush off to the outer islands too quickly. There is a lot of fun to be had on the main island of Papeete as well. If you can manage to be in Papeete for the Heiva festival in July, you're in for a real treat of festival excitement: dancing, cultural shows, sporting events, parades: it's party time in Tahiti for this national holiday. Everyone, local and visitor alike, also heads outdoors for the great annual canoe tournament. All shapes and sizes of canoe, from outriggers to pirogues, singles and doubles to huge 24 man vessels, compete in thrilling races for the crowds. If marine life is your thing, don't miss the Papeete aquarium, entered through a giant shark's mouth. There are also 200 year old turtles to visit not far out of town. Hotels, even if you aren't staying in them, are a hub of visitor activities. You can join day trips to go play with dolphins, feed sharks or feed sting rays. (You can even pet the rays, which will come right up and "kiss" you!) A range of water sports are available, such as water skiing or kite surfing, and hotel restaurants often offer an excellent meal at the end of the day, with evening entertainment such as fire dancing displays. For an authentic local experience and fantastic atmosphere make sure to check out "les roulottes", a kind of mobile food court, by the port, where stall holders open small trucks up to reveal kitchens producing a range of quality dishes. -

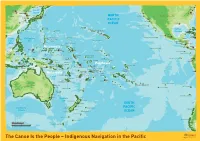

Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific

Hokkaido Vladivostok New York Philadelphia Beijing North Korea Sea of Tianjin Japan P'yongyang Sacramento Washington Seoul Japan Honshu NORTH San Francisco United States of America China South Tokyo Nagoya Korea Pusan Osaka Los Angeles PACIFIC Cheju-Do Shikoku San Diego Shanghai Kyushu OCEAN New Orleans Guadalupe Island (Mex.) Midway Baja Ryukyu Ogasawara- Islands (US) California Trench Okinawa-Jima (Jap.) Gunto (Jap.) Gulf of Miami Minami-Tori- Hawaiian Islands (US) Shima (Jap.) Mexico Havana Taiwan Kauai Cuba Oahu Mexico Hainan Dao Honolulu Guadalajara Jamaica Mariana Mexico Northern Wake Island (US) Hawaii Revillagigedo Island (Mex.) Kingston Philippine Ridge Belize South Luzon Mariana Islands Johnston Atoll (US) China Sea (US) Guatemala Honduras Manila Saipan Sea Guam (US) Marshall Islands El Salvador Nicaragua Philippines Enewetak Managua Costa Rica Panama Yap Islands Micronesia San José Palawan Ratak Clipperton Island (Fr.) Mindanao Pohnpei Chain Davao Melekeok Satawai Panama Chuuk Palikir Majuro Palmyra Atoll (US) Ralik Cocos Islands (CR) Brunei Palau Kosrae Chain Malaysia Line Malpelo Island (Col.) Federated States of Micronesia Gilbert Islands Howland Island (US) Islands Colombia Halmahera Kalimantan Tarawa Baker Island (US) Bismarck Archipelago Quito Jarvis Island (US) Galapagos Islands (Ec.) Sulawesi New Ireland Nauru Guayaquil Phoenix Islands Kiribati Malden Rabaul Ecuador Seram New Guinea Papua Bougainville Solomon Nanumea Vaiaku Indonesia New Guinea New Britain Santa Isabel Islands Polynesia Surabaya Funafuti Marquesas Islands -

1 Final Act of the Multilateral High-Level

FINAL ACT OF THE MULTILATERAL HIGH-LEVEL CONFERENCE ON THE CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF HIGHLY MIGRATORY FISH STOCKS IN THE WESTERN AND CENTRAL PACIFIC I. INTRODUCTION 1. Following the entry into force, on 16 November 1994, of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the South Pacific Forum Fisheries Agency, in December 1994, convened a multilateral high-level conference on South Pacific tuna fisheries. The broad objective of the conference was to promote responsible fishing operations for fishing vessels operating in the South Pacific region, particularly in the light of the United Nations Conference on Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks and the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. Subsequently, following the adoption, in 1995, of the United Nations Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, a second multilateral conference was convened in June 1997 in order to consider issues relating to the establishment of a regional mechanism for the conservation and management of highly migratory fish stocks. That conference agreed that further sessions of the conference should be convened with a view to the establishment of a regional mechanism for conservation and management of the highly migratory fish stocks of the Western and Central Pacific within an overall time-frame of three years from June 1997.1 II. SESSIONS -

Makatea: a Site of Major Importance for Endemic Birds English Pdf 1.92

MAKATEA, A SITE OF MAJOR IMPORTANCE FOR ENDEMIC BIRDS BIODI VERSITY CO NSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 16 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 16 Makatea, a site of major importance for endemic birds Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 16: Makatea, a site of major importance for endemic birds. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Author: Thomas Ghestemme, Société d’Ornithologie de Polynésie Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Cover Photograph: Ducula aurorae © T Ghestemme/SOP Series Editor: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field -

Post Office Box 21, Vavaya Ridge, Honiara, Solomon Islands

NATIONAL SITUATION REPORT 02: Tinakula Volcano Print NATIONAL DISASTER COUNCIL National Disaster Management Office Ministry of Environment, Climate Change, Disaster Management & Meteorology Post Office Box 21, Vavaya Ridge, Honiara, Solomon Islands Phone: (677) 27937, Mobile: 7410874, Fax: (677) 24293 or 27060 E-mail : [email protected] (mailto:[email protected]) NATIONAL SITUATION REPORT 02 Event: Tinakula Volcanic Eruption Date of Issue: 26th October 2017 Time of Issue: 15:30 PM Approved by: N-DOC Chair Issued By: SLB NEOC Next Update: As information become available Sitrep Ref: SR261017002 A. HIGHLIGHTS Volcanic Ash fall is concentrated on Tinakula Island, however, spread over nearby Islands because of the influence of the wind direction Uncertainity on the usage of rain water and bore catchment for household purposes. Signs of complication are now initially reported from some of the villages,this includes, diarrhoea, red eye, skin rush, vomit, and Cough. An Initial Situation Overview (ISO) report has been completed and will be distributed. Outcomes focus on water, health, livelihood, Education and Protection. Water bottles are planned to be shipped to affected communities. A Geologist are deployed to Temotu to monitor the activity SIG Met aviation warning is lifted. N-DOC Health committee are activated and currently supporting the response The estimated population which are expected to be affected is 11,500, however, this can be varied in the coming days as verification continues. Reef Islands and the Polynesian outlayers are most the most vulnerable. 40 Tons of food supply was deployed to Tikopia, Duff and Anuta due to the ongoing food security issues due to the impacts of Tropical Cyclone Donna early this year. -

Chapter 4: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities Supplementary Material

FINAL DRAFT Chapter 4 Supplementary Material IPCC SR Ocean and Cryosphere Chapter 4: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities Supplementary Material Coordinating Lead Authors: Michael Oppenheimer (USA), Bruce Glavovic (New Zealand) Lead Authors: Jochen Hinkel (Germany), Roderik van de Wal (Netherlands), Alexandre K. Magnan (France), Amro Abd-Elgawad (Egypt), Rongshuo Cai (China), Miguel Cifuentes-Jara (Costa Rica), Robert M. Deconto (USA), Tuhin Ghosh (India), John Hay (Cook Islands), Federico Isla (Argentina), Ben Marzeion (Germany), Benoit Meyssignac (France), Zita Sebesvari (Hungary/Germany) Contributing Authors: Robbert Biesbroek (Netherlands), Maya K. Buchanan (USA), Gonéri Le Cozannet (France), Catia Domingues (Australia), Sönke Dangendorf (Germany), Petra Döll (Germany), Virginie K.E. Duvat (France), Tamsin Edwards (UK), Alexey Ekaykin (Russian Federation), Donald Forbes (Canada), James Ford (UK), Miguel D. Fortes (Philippines), Thomas Frederikse (Netherlands), Jean-Pierre Gattuso (France), Robert Kopp (USA), Erwin Lambert (Netherlands), Judy Lawrence (New Zealand), Andrew Mackintosh (New Zealand), Angélique Melet (France), Elizabeth McLeod (USA), Mark Merrifield (USA), Siddharth Narayan (US), Robert J. Nicholls (UK), Fabrice Renaud (UK), Jonathan Simm (UK), AJ Smit (South Africa), Catherine Sutherland (South Africa), Nguyen Minh Tu (Vietnam), Jon Woodruff (USA), Poh Poh Wong (Singapore), Siyuan Xian (USA) Review Editors: Ayako Abe-Ouchi (Japan), Kapil Gupta (India), Joy Pereira (Malaysia) Chapter -

Atoll Research Bulletin No. 503 the Vascular Plants Of

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 503 THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF MAJURO ATOLL, REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS BY NANCY VANDER VELDE ISSUED BY NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON, D.C., U.S.A. AUGUST 2003 Uliga Figure 1. Majuro Atoll THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF MAJURO ATOLL, REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS ABSTRACT Majuro Atoll has been a center of activity for the Marshall Islands since 1944 and is now the major population center and port of entry for the country. Previous to the accompanying study, no thorough documentation has been made of the vascular plants of Majuro Atoll. There were only reports that were either part of much larger discussions on the entire Micronesian region or the Marshall Islands as a whole, and were of a very limited scope. Previous reports by Fosberg, Sachet & Oliver (1979, 1982, 1987) presented only 115 vascular plants on Majuro Atoll. In this study, 563 vascular plants have been recorded on Majuro. INTRODUCTION The accompanying report presents a complete flora of Majuro Atoll, which has never been done before. It includes a listing of all species, notation as to origin (i.e. indigenous, aboriginal introduction, recent introduction), as well as the original range of each. The major synonyms are also listed. For almost all, English common names are presented. Marshallese names are given, where these were found, and spelled according to the current spelling system, aside from limitations in diacritic markings. A brief notation of location is given for many of the species. The entire list of 563 plants is provided to give the people a means of gaining a better understanding of the nature of the plants of Majuro Atoll. -

THE LIMITS of SELF-DETERMINATION in OCEANIA Author(S): Terence Wesley-Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies, Vol

THE LIMITS OF SELF-DETERMINATION IN OCEANIA Author(s): Terence Wesley-Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies, Vol. 56, No. 1/2, The Caribbean and Pacific in a New World Order (March/June 2007), pp. 182-208 Published by: Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, University of the West Indies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27866500 . Accessed: 11/10/2013 20:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of the West Indies and Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social and Economic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 133.30.14.128 on Fri, 11 Oct 2013 20:07:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Social and Economic Studies 56:1&2 (2007): 182-208 ISSN:0037-7651 THE LIMITS OF SELF-DETERMINATION IN OCEANIA Terence Wesley-Smith* ABSTRACT This article surveys processes of decolonization and political development inOceania in recent decades and examines why the optimism of the early a years of self government has given way to persistent discourse of crisis, state failure and collapse in some parts of the region. -

Suva and Lautoka

WHO WE ARE: • Pacific Direct Line (PDL) is a Shipping Company specialising in providing liner shipper services to the South Pacific Region. • We have been trading in the region for over 40 years • The Company has been owned and managed by the same family since it’s formation and prides itself on the close family bond which is the backbone of the company and all its subsidiary businesses. • In 2006 PDL sold 51% of the business to Pacific International Line (PIL) in Singapore. • Our core business has been to provide shipping services from New Zealand and Australia to the Pacific Islands, but we have repositioned the business over the last five years to also provide feedering services for various international operators. WHAT WE DO: • We offer liner shipping services to 16 countries and 22 ports including Fiji, (Suva and Lautoka) Samoa, American Samoa, Tonga, (Nuku’alofa), Wallis and Futuna, Funafuti, Vanuatu, ( Port Vila and Santo) New Caledonia, Tahiti, the Cook Islands (Rarotonga), Norfolk, Tarawa and Majuro. • PDL owns Transam Agencies throughout the Pacific, ensuring consistent standards and levels of service across the region. (see attached) • Our fleet of vessels are chartered mainly from our parent company, (PIL) and we are constantly upgrading our fleet to larger brand new vessels purpose built for this unique trade. This advantage allows us to select our vessels to cater for the growth in the volume from the influx of transhipment containers to the South Pacific. • We are developing “bolt on” businesses ensuring vertical integration of our services across cartage, consolidation, stevedoring, container depots… • PDL employs approximately 300 people throughout the Pacific in our shipping, agency and subsidiary companies. -

SPX Schedule EB

South Pacific Express Connection Schedule EASTBOUND SAILINGS September 2021 - December 2021 Connecting the South Pacific with the US September 21, 2021 Origin Vessel | Auckland | Nuku'alofa | Lautoka | Suva Eastbound Sailings │Papeete | Pago Pago │ Apia │ Nukualofa | Honolulu │ US West Coast Origin Vessel Auckland Nukualofa Lautoka Suva Apia Arrivals Papeete Pago Pago Apia Long Beach Oakland Honolulu Manoa 444W Imua 106 Arkadia 531 Sailed 9/15 Sailed 9/20 Wed, 22-Sep Thu, 23-Sep Tue, 28-Sep Fri, 24-Sep Thu, 30-Sep Wed, 29-Sep Thu, 14-Oct Sat, 16-Oct Sat, 23-Oct Manoa 445W Olomana 134 Cap Salia 967 Mon, 27-Sep Sun, 3-Oct Omit Tue, 5-Oct Sun, 10-Oct Mon, 11-Oct Sat, 16-Oct Sat, 16-Oct Sat, 30-Oct Mon, 1-Nov Sat, 6-Nov R J Pfeiffer 486W Imua 107 Arkadia 532 Wed, 13-Oct Tue, 19-Oct Thu, 21-Oct Fri, 22-Oct Wed, 27-Oct Wed, 27-Oct Tue, 2-Nov Mon, 1-Nov Tue, 16-Nov Thu, 18-Nov Sat, 27-Nov Olomana 135 Cap Salia 968 Wed, 27-Oct Tue, 2-Nov Omit Thu, 4-Nov Tue, 9-Nov Fri, 12-Nov Wed, 17-Nov Wed, 17-Nov Thu, 2-Dec Sat, 4-Dec Imua 108 Arkadia 533 Wed, 17-Nov Tue, 23-Nov Thu, 25-Nov Fri, 26-Nov Wed, 1-Dec Mon, 29-Nov Sat, 4-Dec Sat, 4-Dec Sun, 19-Dec Tue, 21-Dec 1 Agents and Offices U.S. Ports Pago Pago, American Samoa Papeete, Tahiti Matson Customer Service Center Molida Shipping Agency, Ltd Papeete Seairland Transports Tel: 1-866-662-4826 Tel: (684) 633-2777 Tel: (689) 40549700 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Apia, Samoa Nukualofa, Tonga Christmas Island Molida Shipping Agency, Ltd.